The Campaign To Bring Mumia Home

Stand with Mumia, his legal representatives and his supporters as Mumia has stood with us since the age of 14, as a leading figure in the Philadelphia Black Panther Party. His legal team will be in court petitioning to have the explosive new evidence heard and litigated allowing for a reopening of the Appeals process, which the Common Pleas Court Judge Lucretia Clemons will be deciding if the new evidence warrants an impartial hearing, leading to a new trial or outright release.

· That new evidence being a key witness testifying against Mumia in the original 1981 trial, asking the former DA, Joseph Mc Gil "where is my money? I've been trying to contact you"

· Ineffective counsel and jury fixing to keep Blacks off of high profile cases

The Campaign to Bring Mumia Home has a charter bus leaving NYC at 5:30 AM, headed to Philadelphia to protest a fraudulent conviction and patently unfair trial fraught with over 21 Constitutional violations. Go toBringmumiahome.com to purchase your ticket, $30. Call the Free Mumia Coalition hotline for more details. (212) 330-8029

We expect to be back in NYC by 4:00PM.

When We Fight We Win!

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

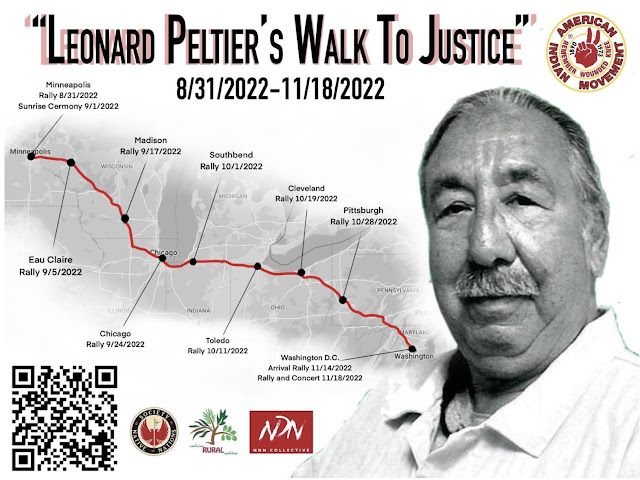

Leonard Peltier’s Walk to Justice Demands Release of Political Prisoner

Minneapolis, Minnesota – On September 1, Leonard Peltier’s Walk to Justice departed from Minneapolis, Minnesota. The march will pass through multiple cities, finally ending in Washington, DC on November 14. Rallies and prayer sessions will be held along the route. The walk is being coordinated by the American Indian Movement Grand Governing Council to demand elder Leonard Peltier’s release from federal prison.

Leonard Peltier’s fight for justice

Leonard Peltier has been unjustly held as a political prisoner by the U.S. government for over 46 years, making him one of the world’s longest incarcerated political prisoners. He is the longest held Native American political prisoner in the world. Peltier was wrongly convicted and framed for a shooting at Oglala on June 26, 1975.

At the time, members of the Lakota Nation on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation were being endlessly terrorized and targeted by paramilitaries led by the corrupt, U.S.-government backed tribal chairman Dick Wilson. 64 people were killed by these paramilitaries between 1973 and 1975. The Lakota people called on the American Indian Movement (AIM) for protection, and Peltier answered the call. During the night of June 26, 1975, plainclothes FBI officers raided the AIM encampment at Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. A shootout ensued, and two FBI officers, Jack Coler and Ronald Williams, and one Native man, Joe Stuntz, were left dead.

In the ridiculous trial that followed, the two other Native defendants, Bob Robideau and Dino Butler, were completely exonerated. Peltier, on the other hand, was used to make an example. The FBI coerced a statement from a Native woman who had never met Peltier at the time she gave her statement. This false evidence was used to extradite Peltier from Canada, where he had fled after the shootout, and is used to imprison Peltier to this day.

The struggle continues

Leonard’s true “crime” is daring to fight back against the everyday oppression Native people face under the imperialist regime of the United States. Growing up on the Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation in North Dakota, Leonard lived through the U.S. government’s genocidal programs to forcibly assimilate Native peoples. Recently, Peltier opened up about his experiences in the Wahpeton Indian School. This was one of many boarding schools used to brutalize Native children into leaving behind their culture. Children were beaten constantly, especially for practicing any portions of their culture or speaking their language. Many didn’t make it out alive. This was part of the U.S. government‘s larger policy of intensifying attacks on the sovereignty of the First Nations. These experiences, among many more, led Peltier to become a member of the American Indian Movement to continue the fight back against genocide of Native peoples.

Peltier is a lifelong liberation fighter who has sacrificed immensely for the movement. He is also a 77-year-old elder with numerous chronic health problems, exacerbated by his fight with COVID earlier this year. Despite his innocence and health problems, the U.S. government has refused repeated calls for clemency for Peltier. Throughout his years of imprisonment, many have demanded Peltier’s freedom, including Nelson Mandela and, most recently, a UN Human Rights Council working group.

The time for Leonard Peltier to finally be released from prison is now. Join the fight to free Leonard Peltier, and to free all political prisoners!

There are many ways to support the march and strengthen the call to free Peltier. These include:

· Joining all or part of the walk

· Joining a rally

· Sponsoring the caravan with a hot prepared meal

· Dry food donations

· Hosting lodging/camping

· Driving a support vehicle

· Raising awareness of Peltier’s cause locally

· Promoting the caravan and rally

Monetary donations (can be sent via PayPal here)

Those interested in volunteering with the caravan can sign up here.

Learn more about Leonard Peltier and his case here:

http://www.whoisleonardpeltier.info/home/about-us/

—Liberation News, September 3, 2022

https://popularresistance.org/leonard-peltiers-walk-to-justice-demands-release-of-political-prisoner/

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

The US sanctions and embargo are preventing Cuba from rebuilding after Hurricane Ian.

The Biden Administration needs to act right now to help the Cuban people. Hurricane Ian caused great devastation. The power grid was damaged, and the electrical system collapsed. Over four thousand homes have been completely destroyed or badly damaged.

Cuba must be allowed, even if just for the next six months, to purchase the necessary construction materials to REBUILD. Cubans are facing a major humanitarian crisis because of Hurricane Ian.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

URGENT ACTION NEEDED!

We demand that ALL "illegal abortion" charges against Madison County, Nebraska women be dropped

In Madison County, Nebraska, two women- one the mother of a pregnant teenager who was a minor at the time of her pregnancy and is being charged as an adult- are facing prosecution for self managing an abortion. In an outrageous violation of civil liberties, Facebook assisted the police and county attorney in this case by turning over communication between the daughter and her mother regarding obtaining abortion pills which is not illegal in Nebraska. The prosecutor has used this information to charge the daughter, her mother, and a male friend who assisted them after the fact with illegal abortion along with additional trumped up charges of "concealing a body."

We demand that ALL charges be dropped against all three of them and we ask that you call the office of Madison County Attorney Joseph Smith at 402-454-3311 Ext. 206 with the following:

"I am calling to demand that all charges against Jessica Burgess, her daughter, and their friend be dropped. In your own words- no charges like this have ever been brought before. That is because criminalizing abortion is unjust and unconstitutional. We will not stand for any charges being brought against any pregnant person for the outcome of their pregnancy OR anyone who assists that pregnant person. Drop all charges NOW."

You can also email County Attorney Smith here.

If you pledged to #AidAndAbetAbortion- NOW is the time to stand up for these women in Nebraska as this could be any of us in the future.

About NWL

National Women's Liberation (NWL) is a multiracial feminist group for women who want to fight male supremacy and gain more freedom for women. Our priorities are abortion and birth control, overthrowing the double day, and feminist consciousness-raising.

NWL meetings are for women and tranpeople who do not benefit from male supremacy because we believe we should lead the fight for our liberation. In addition, women of color meet separately from white women in Women of Color Caucus (WOCC) meetings to examine their experiences with white supremacy and how it intersects with male supremacy to oppress women of color.

Learn more at womensliberation.org.

Questions? Email nwl@womensliberation.org for more info.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Doctors for Assange Statement

Doctors to UK: Assange Extradition

‘Medically & Ethically’ Wrong

https://consortiumnews.com/2022/06/12/doctors-to-uk-assange-extradition-medically-ethically-wrong/

Ahead of the U.K. Home Secretary’s decision on whether to extradite Julian Assange to the United States, a group of more than 300 doctors representing 35 countries have told Priti Patel that approving his extradition would be “medically and ethically unacceptable”.

In an open letter sent to the Home Secretary on Friday June 10, and copied to British Prime Minster Boris Johnson, the Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice Robert Buckland, the Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and the Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong, the doctors draw attention to the fact that Assange suffered a “mini stroke” in October 2021. They note:

“Predictably, Mr Assange’s health has since continued to deteriorate in your custody. In October 2021 Mr. Assange suffered a ‘mini-stroke’… This dramatic deterioration of Mr Assange’s health has not yet been considered in his extradition proceedings. The US assurances accepted by the High Court, therefore, which would form the basis of any extradition approval, are founded upon outdated medical information, rendering them obsolete.”

The doctors charge that any extradition under these circumstances would constitute negligence. They write:

“Under conditions in which the UK legal system has failed to take Mr Assange’s current health status into account, no valid decision regarding his extradition may be made, by yourself or anyone else. Should he come to harm in the US under these circumstances it is you, Home Secretary, who will be left holding the responsibility for that negligent outcome.”

In their letter the group reminds the Home Secretary that they first wrote to her on Friday 22 November 2019, expressing their serious concerns about Julian Assange’s deteriorating health.

Those concerns were subsequently borne out by the testimony of expert witnesses in court during Assange’s extradition proceedings, which led to the denial of his extradition by the original judge on health grounds. That decision was later overturned by a higher court, which referred the decision to Priti Patel in light of US assurances that Julian Assange would not be treated inhumanely.

The doctors write:

“The subsequent ‘assurances’ of the United States government, that Mr Assange would not be treated inhumanly, are worthless given their record of pursuit, persecution and plotted murder of Mr Assange in retaliation for his public interest journalism.”

They conclude:

“Home Secretary, in making your decision as to extradition, do not make yourself, your government, and your country complicit in the slow-motion execution of this award-winning journalist, arguably the foremost publisher of our time. Do not extradite Julian Assange; free him.”

Julian Assange remains in High Security Belmarsh Prison awaiting Priti Patel’s decision, which is due any day.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Sign the petition:

https://dontextraditeassange.com/petition/

If extradited to the United States, Julian Assange, father of two young British children, would face a sentence of 175 years in prison merely for receiving and publishing truthful information that revealed US war crimes.

UK District Judge Vanessa Baraitser has ruled that "it would be oppressive to extradite him to the United States of America".

Amnesty International states, “Were Julian Assange to be extradited or subjected to any other transfer to the USA, Britain would be in breach of its obligations under international law.”

Human Rights Watch says, “The only thing standing between an Assange prosecution and a major threat to global media freedom is Britain. It is urgent that it defend the principles at risk.”

The NUJ has stated that the “US charges against Assange pose a huge threat, one that could criminalise the critical work of investigative journalists & their ability to protect their sources”.

Julian will not survive extradition to the United States.

The UK is required under its international obligations to stop the extradition. Article 4 of the US-UK extradition treaty says: "Extradition shall not be granted if the offense for which extradition is requested is a political offense."

The decision to either Free Assange or send him to his death is now squarely in the political domain. The UK must not send Julian to the country that conspired to murder him in London.

The United Kingdom can stop the extradition at any time. It must comply with Article 4 of the US-UK Extradition Treaty and Free Julian Assange.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Dear friends,

Recently I’ve started working with the Coalition to Free Ruchell Magee. On March 17, Ruchell turned 83. He’s been imprisoned for 59 years, and now walks with a walker. He is no threat to society if released. Ruchell was in the Marin County Courthouse on August 7, 1970, the morning Jonathan Jackson took it over in an effort to free his older brother, the internationally known revolutionary prison writer, George Jackson. Ruchell joined Jonathan and was the only survivor of the shooting that ensued. He has been locked up ever since and denied parole 13 times. On March 19, the Coalition to Free Ruchell Magee held a webinar for Ruchell for his 83rd birthday, which was a terrific event full of information and plans for building the campaign to Free Ruchell. (For information about his case, please visit: www.freeruchellmagee.org.)

Below are two ways to stream this historic webinar, plus

• a petition you can sign

• a portal to send a letter to Governor Newsom

• a Donate button to support his campaign

• a link to our campaign website.

Please take a moment and help.

Note: We will soon have t-shirts to sell to raise money for legal expenses.

Here is the YouTube link to view the March 19 Webinar:

https://youtu.be/4u5XJzhv9Hc

Here is the Facebook link:

https://fb.watch/bTMr6PTuHS/

Sign the petition to Free Ruchell:

https://actionnetwork.org/petitions/governor-newsom-free-82-year-old-prisoner-ruchell-magee-unjustly-incarcerated-for-58-years

Write to Governor Newsom’s office:

https://actionnetwork.org/letters/free-82-year-old-prisoner-ruchell-magee-unjustly-incarcerated-for-58-years?source=direct_link

Donate:

https://www.paypal.com/donate/?hosted_button_id=GVZG9CZ375PVG

Ruchell’s Website:

www.freeruchellmagee.org

Thanks,

Charlie Hinton

ch.lifewish@gmail.com

No one ever hurt their eyes by looking on the bright side

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Tell Congress to Help #FreeDanielHale

U.S. Air Force veteran, Daniel Everette Hale has recently completed his first year of a 45-month prison sentence for exposing the realities of U.S drone warfare. Daniel Hale is not a spy, a threat to society, or a bad faith actor. His revelations were not a threat to national security. If they were, the prosecution would be able to identify the harm caused directly from the information Hale made public. Our members of Congress can urge President Biden to commute Daniel's sentence! Either way, Daniel deserves to be free.

https://oneclickpolitics.global.ssl.fastly.net/messages/edit?promo_id=16979

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Laws are created to be followed

by the poor.

Laws are made by the rich

to bring some order to exploitation.

The poor are the only law abiders in history.

When the poor make laws

the rich will be no more.

—Roque Dalton Presente!

(May 14, 1935 – Assassinated May 10, 1975)[1]

[1] Roque Dalton was a Salvadoran poet, essayist, journalist, political activist, and intellectual. He is considered one of Latin America's most compelling poets.

Poems:

http://cordite.org.au/translations/el-salvador-tragic/

About:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roque_Dalton

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

“In His Defense” The People vs. Kevin Cooper

A film by Kenneth A. Carlson

Teaser is now streaming at:

https://www.carlsonfilms.com

Posted by: Death Penalty Focus Blog, January 10, 2022

https://deathpenalty.org/teaser-for-a-kevin-cooper-documentary-is-now-streaming/?eType=EmailBlastContent&eId=1c7299ab-018c-4780-9e9d-54cab2541fa0

“In his Defense,” a documentary on the Kevin Cooper case, is in the works right now, and California filmmaker Kenneth Carlson has released a teaser for it on CarlsonFilms.com

Just over seven months ago, California Gov. Gavin Newsom ordered an independent investigation of Cooper’s death penalty case. At the time, he explained that, “In cases where the government seeks to impose the ultimate punishment of death, I need to be satisfied that all relevant evidence is carefully and fairly examined.”

That investigation is ongoing, with no word from any of the parties involved on its progress.

Cooper has been on death row since 1985 for the murder of four people in San Bernardino County in June 1983. Prosecutors said Cooper, who had escaped from a minimum-security prison and had been hiding out near the scene of the murder, killed Douglas and Peggy Ryen, their 10-year-old daughter, Jessica, and 10-year-old Chris Hughes, a friend who was spending the night at the Ryen’s. The lone survivor of the attack, eight-year-old Josh Ryen, was severely injured but survived.

For over 36 years, Cooper has insisted he is innocent, and there are serious questions about evidence that was missing, tampered with, destroyed, possibly planted, or hidden from the defense. There were multiple murder weapons, raising questions about how one man could use all of them, killing four people and seriously wounding one, in the amount of time the coroner estimated the murders took place.

The teaser alone gives a good overview of the case, and helps explain why so many believe Cooper was wrongfully convicted.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

New Legal Filing in Mumia’s Case

The following statement was issued January 4, 2022, regarding new legal filings by attorneys for Mumia Abu-Jamal.

Campaign to Bring Mumia Home

In her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, Zora Neale Hurston wrote, “There are years that ask questions, and years that answer.”

With continued pressure from below, 2022 will be the year that forces the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office and the Philly Police Department to answer questions about why they framed imprisoned radio journalist and veteran Black Panther Mumia Abu-Jamal. Abu-Jamal’s attorneys have filed a Pennsylvania Post Conviction Relief Act (PCRA) petition focused entirely on the six boxes of case files that were found in a storage room of the DA’s office in late December 2018, after the case being heard before Judge Leon Tucker in the Court of Common Pleas concluded. (tinyurl.com/zkyva464)

The new evidence contained in the boxes is damning, and we need to expose it. It reveals a pattern of misconduct and abuse of authority by the prosecution, including bribery of the state’s two key witnesses, as well as racist exclusion in jury selection—a violation of the landmark Supreme Court decision Batson v. Kentucky. The remedy for each or any of the claims in the petition is a new trial. The court may order a hearing on factual issues raised in the claims. If so, we won’t know for at least a month.

The new evidence includes a handwritten letter penned by Robert Chobert, the prosecution’s star witness. In it, Chobert demands to be paid money promised him by then-Prosecutor Joseph McGill. Other evidence includes notes written by McGill, prominently tracking the race of potential jurors for the purposes of excluding Black people from the jury, and letters and memoranda which reveal that the DA’s office sought to monitor, direct, and intervene in the outstanding prostitution charges against its other key witness Cynthia White.

Mumia Abu-Jamal was framed and convicted 40 years ago in 1982, during one of the most corrupt and racist periods in Philadelphia’s history—the era of cop-turned-mayor Frank Rizzo. It was a moment when the city’s police department, which worked intimately with the DA’s office, routinely engaged in homicidal violence against Black and Latinx detainees, corruption, bribery and tampering with evidence to obtain convictions.

In 1979, under pressure from civil rights activists, the Department of Justice filed an unprecedented lawsuit against the Philadelphia police department and detailed a culture of racist violence, widespread corruption and intimidation that targeted outspoken people like Mumia. Despite concurrent investigations by the FBI and Pennsylvania’s Attorney General and dozens of police convictions, the power and influence of the country’s largest police association, the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) prevailed.

Now, more than 40 years later, we’re still living with the failure to uproot these abuses. Philadelphia continues to fear the powerful FOP, even though it endorses cruelty, racism, and multiple injustices. A culture of fear permeates the “city of brotherly love.”

The contents of these boxes shine light on decades of white supremacy and rampant lawlessness in U.S. courts and prisons. They also hold enormous promise for Mumia’s freedom and challenge us to choose Love, Not PHEAR. (lovenotphear.com/) Stay tuned.

—Workers World, January 4, 2022

https://www.workers.org/2022/01/60925/

Pa. Supreme Court denies widow’s appeal to remove Philly DA from Abu-Jamal case

Abu Jamal was convicted by a jury of first-degree murder of Faulkner in 1982. Over the past four decades, five of his appeals have been quashed.

In 1989, the state’s highest court affirmed Abu-Jamal’s death penalty conviction, and in 2012, he was re-sentenced to life in prison.

Abu-Jamal, 66, remains in prison. He can appeal to the state Supreme Court, or he can file a new appeal.

KYW Newsradio reached out to Abu-Jamal’s attorneys for comment. They shared this statement in full:

“Today, the Superior Court concluded that it lacked jurisdiction to consider issues raised by Mr. Abu-Jamal in prior appeals. Two years ago, the Court of Common Pleas ordered reconsideration of these appeals finding evidence of an appearance of judicial bias when the appeals were first decided. We are disappointed in the Superior Court’s decision and are considering our next steps.

“While this case was pending in the Superior Court, the Commonwealth revealed, for the first time, previously undisclosed evidence related to Mr. Abu-Jamal’s case. That evidence includes a letter indicating that the Commonwealth promised its principal witness against Mr. Abu-Jamal money in connection with his testimony. In today’s decision, the Superior Court made clear that it was not adjudicating the issues raised by this new evidence. This new evidence is critical to any fair determination of the issues raised in this case, and we look forward to presenting it in court.”

https://www.audacy.com/kywnewsradio/news/local/pennsylvania-superior-court-rejects-mumia-abu-jamal-appeal-ron-castille

Questions and comments may be sent to: info@freedomarchives.org

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Sign our petition urging President Biden to grant clemency to Leonard Peltier.

https://www.freeleonardpeltier.com/petition

Email: contact@whoisleonardpeltier.info

Address: 116 W. Osborne Ave. Tampa, Florida 33603

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

How long will he still be with us? How long will the genocide continue?

By Michael Moore

American Indian Movement leader, Leonard Peltier, at 77 years of age, came down with Covid-19 this weekend. Upon hearing this, I broke down and cried. An innocent man, locked up behind bars for 44 years, Peltier is now America’s longest-held political prisoner. He suffers in prison tonight even though James Reynolds, one of the key federal prosecutors who sent Peltier off to life in prison in 1977, has written to President Biden and confessed to his role in the lies, deceit, racism and fake evidence that together resulted in locking up our country’s most well-known Native American civil rights leader. Just as South Africa imprisoned for more than 27 years its leading voice for freedom, Nelson Mandela, so too have we done the same to a leading voice and freedom fighter for the indigenous people of America. That’s not just me saying this. That’s Amnesty International saying it. They placed him on their political prisoner list years ago and continue to demand his release.

And it’s not just Amnesty leading the way. It’s the Pope who has demanded Leonard Peltier’s release. It’s the Dalai Lama, Jesse Jackson, and the President Pro-Tempore of the US Senate, Sen. Patrick Leahy. Before their deaths, Nelson Mandela, Mother Theresa and Bishop Desmond Tutu pleaded with the United States to free Leonard Peltier. A worldwide movement of millions have seen their demands fall on deaf ears.

And now the calls for Peltier to be granted clemency in DC have grown on Capitol Hill. Senator Brian Schatz (D-HI), the head of the Senate committee who oversees the Bureau of Indian Affairs, has also demanded Peltier be given his freedom. Numerous House Democrats have also written to Biden.

The time has come for our President to act; the same President who appointed the first-ever Native American cabinet member last year and who halted the building of the Keystone pipeline across Native lands. Surely Mr. Biden is capable of an urgent act of compassion for Leonard Peltier — especially considering that the prosecutor who put him away in 1977 now says Peltier is innocent, and that his US Attorney’s office corrupted the evidence to make sure Peltier didn’t get a fair trial. Why is this victim of our judicial system still in prison? And now he is sick with Covid.

For months Peltier has begged to get a Covid booster shot. Prison officials refused. The fact that he now has COVID-19 is a form of torture. A shame hangs over all of us. Should he now die, are we all not complicit in taking his life?

President Biden, let Leonard Peltier go. This is a gross injustice. You can end it. Reach deep into your Catholic faith, read what the Pope has begged you to do, and then do the right thing.

For those of you reading this, will you join me right now in appealing to President Biden to free Leonard Peltier? His health is in deep decline, he is the voice of his people — a people we owe so much to for massacring and imprisoning them for hundreds of years.

The way we do mass incarceration in the US is abominable. And Leonard Peltier is not the only political prisoner we have locked up. We have millions of Black and brown and poor people tonight in prison or on parole and probation — in large part because they are Black and brown and poor. THAT is a political act on our part. Corporate criminals and Trump run free. The damage they have done to so many Americans and people around the world must be dealt with.

This larger issue is one we MUST take on. For today, please join me in contacting the following to show them how many millions of us demand that Leonard Peltier has suffered enough and should be free:

President Joe Biden

Phone: 202-456-1111

E-mail: At this link

https://www.whitehouse.gov/contact/

Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland

Phone: 202-208-3100

E-mail: feedback@ios.doi.gov

Attorney General Merrick Garland

Phone: 202-514-2000

E-mail: At this link

https://www.justice.gov/doj/webform/your-message-department-justice

I’ll end with the final verse from the epic poem “American Names” by Stephen Vincent Benet:

I shall not rest quiet in Montparnasse.

I shall not lie easy at Winchelsea.

You may bury my body in Sussex grass,

You may bury my tongue at Champmedy.

I shall not be there. I shall rise and pass.

Bury my heart at Wounded Knee.

PS. Also — watch the brilliant 1992 documentary by Michael Apted and Robert Redford about the framing of Leonard Peltier— “Incident at Oglala”

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

The Moment

By Margaret Atwood*

The moment when, after many years

of hard work and a long voyage

you stand in the centre of your room,

house, half-acre, square mile, island, country,

knowing at last how you got there,

and say, I own this,

is the same moment when the trees unloose

their soft arms from around you,

the birds take back their language,

the cliffs fissure and collapse,

the air moves back from you like a wave

and you can't breathe.

No, they whisper. You own nothing.

You were a visitor, time after time

climbing the hill, planting the flag, proclaiming.

We never belonged to you.

You never found us.

It was always the other way round.

*Witten by the woman who wrote a novel about Christian fascists taking over the U.S. and enslaving women. Prescient!

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Union Membership—2021

Bureau of Labor Statistics

U.S. Department of Labor

For release 10:00 a.m. (ET) Thursday, January 20, 2022

Technical information:

(202) 691-6378 • cpsinfo@bls.gov • www.bls.gov/cps

Media contact:

(202) 691-5902 • PressOffice@bls.gov

In 2021, the number of wage and salary workers belonging to unions continued to decline (-241,000) to 14.0 million, and the percent who were members of unions—the union membership rate—was 10.3 percent, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. The rate is down from 10.8 percent in 2020—when the rate increased due to a disproportionately large decline in the total number of nonunion workers compared with the decline in the number of union members. The 2021 unionization rate is the same as the 2019 rate of 10.3 percent. In 1983, the first year for which comparable union data are available, the union membership rate was 20.1 percent and there were 17.7 million union workers.

These data on union membership are collected as part of the Current Population Survey (CPS), a monthly sample survey of about 60,000 eligible households that obtains information on employment and unemployment among the nation’s civilian noninstitutional population age 16 and over. For further information, see the Technical Note in this news release.

Highlights from the 2021 data:

• The union membership rate of public-sector workers (33.9 percent) continued to be more than five times higher than the rate of private-sector workers (6.1 percent). (See table 3.)

• The highest unionization rates were among workers in education, training, and library occupations (34.6 percent) and protective service occupations (33.3 percent). (See table 3.)

• Men continued to have a higher union membership rate (10.6 percent) than women (9.9 percent). The gap between union membership rates for men and women has narrowed considerably since 1983 (the earliest year for which comparable data are available), when rates for men and women were 24.7 percent and 14.6 percent, respectively. (See table 1.)

• Black workers remained more likely to be union members than White, Asian, or Hispanic workers. (See table 1.)

• Nonunion workers had median weekly earnings that were 83 percent of earnings for workers who were union members ($975 versus $1,169). (The comparisons of earnings in this news release are on a broad level and do not control for many factors that can be important in explaining earnings differences.) (See table 2.)

• Among states, Hawaii and New York continued to have the highest union membership rates (22.4 percent and 22.2 percent, respectively), while South Carolina and North Carolina continued to have the lowest (1.7 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively). (See table 5.)

Industry and Occupation of Union Members

In 2021, 7.0 million employees in the public sector belonged to unions, the same as in the private sector. (See table 3.)

Union membership decreased by 191,000 over the year in the public sector. The public-sector union membership rate declined by 0.9 percentage point in 2021 to 33.9 percent, following an increase of 1.2 percentage points in 2020. In 2021, the union membership rate continued to be highest in local government (40.2 percent), which employs many workers in heavily unionized occupations, such as police officers, firefighters, and teachers.

The number of union workers employed in the private sector changed little over the year. However, the number of private-sector nonunion workers increased in 2021. The private-sector unionization rate declined by 0.2 percentage point in 2021 to 6.1 percent, slightly lower than its 2019 rate of 6.2 percent. Industries with high unionization rates included utilities (19.7 percent), motion pictures and sound recording industries (17.3 percent), and transportation and warehousing (14.7 percent). Low unionization rates occurred in finance (1.2 percent), professional and technical services (1.2 percent), food services and drinking places (1.2 percent), and insurance (1.5 percent).

Among occupational groups, the highest unionization rates in 2021 were in education, training, and library occupations (34.6 percent) and protective service occupations (33.3 percent). Unionization rates were lowest in food preparation and serving related occupations (3.1 percent); sales and related occupations (3.3 percent); computer and mathematical occupations (3.7 percent); personal care and service occupations (3.9 percent); and farming, fishing, and forestry occupations (4.0 percent).

Selected Characteristics of Union Members

In 2021, the number of men who were union members, at 7.5 million, changed little, while the number of women who were union members declined by 182,000 to 6.5 million. The unionization rate for men decreased by 0.4 percentage point over the year to 10.6 percent. In 2021, women’s union membership rate declined by 0.6 percentage point to 9.9 percent. The 2021 decreases in union membership rates for men and women reflect increases in the total number of nonunion workers. The rate for men is below the 2019 rate (10.8 percent), while the rate for women is above the 2019 rate (9.7 percent). (See table 1.)

Among major race and ethnicity groups, Black workers continued to have a higher union membership rate in 2021 (11.5 percent) than White workers (10.3 percent), Asian workers (7.7 percent), and Hispanic workers (9.0 percent). The union membership rate declined by 0.4 percentage point for White workers, by 0.8 percentage point for Black workers, by 1.2 percentage points for Asian workers, and by 0.8 percentage point for Hispanic workers. The 2021 rates for Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics are little or no different from 2019, while the rate for Asians is lower.

By age, workers ages 45 to 54 had the highest union membership rate in 2021, at 13.1 percent. Younger workers—those ages 16 to 24—had the lowest union membership rate, at 4.2 percent.

In 2021, the union membership rate for full-time workers (11.1 percent) continued to be considerably higher than that for part-time workers (6.1 percent).

Union Representation

In 2021, 15.8 million wage and salary workers were represented by a union, 137,000 less than in 2020. The percentage of workers represented by a union was 11.6 percent, down by 0.5 percentage point from 2020 but the same as in 2019. Workers represented by a union include both union members (14.0 million) and workers who report no union affiliation but whose jobs are covered by a union contract (1.8 million). (See table 1.)

Earnings

Among full-time wage and salary workers, union members had median usual weekly earnings of $1,169 in 2021, while those who were not union members had median weekly earnings of $975. In addition to coverage by a collective bargaining agreement, these earnings differences reflect a variety of influences, including variations in the distributions of union members and nonunion employees by occupation, industry, age, firm size, or geographic region. (See tables 2 and 4.)

Union Membership by State

In 2021, 30 states and the District of Columbia had union membership rates below that of the U.S. average, 10.3 percent, while 20 states had rates above it. All states in both the East South Central and West South Central divisions had union membership rates below the national average, while all states in both the Middle Atlantic and Pacific divisions had rates above it. (See table 5 and chart 1.)

Ten states had union membership rates below 5.0 percent in 2021. South Carolina had the lowest rate (1.7 percent), followed by North Carolina (2.6 percent) and Utah (3.5 percent). Two states had union membership rates over 20.0 percent in 2021: Hawaii (22.4 percent) and New York (22.2 percent).

In 2021, about 30 percent of the 14.0 million union members lived in just two states (California at 2.5 million and New York at 1.7 million). However, these states accounted for about 17 percent of wage and salary employment nationally.

Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic Impact on 2021 Union Members Data

Union membership data for 2021 continue to reflect the impact on the labor market of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Comparisons with union membership measures for 2020, including metrics such as the union membership rate and median usual weekly earnings, should be interpreted with caution. The onset of the pandemic in 2020 led to an increase in the unionization rate due to a disproportionately large decline in the number of nonunion workers compared with the decline in the number of union members. The decrease in the rate in 2021 reflects a large gain in the number of nonunion workers and a decrease in the number of union workers. More information on labor market developments in recent months is available at:

www.bls.gov/covid19/effects-of-covid-19-pandemic-and- response-on-the-employment-situation-news-release.htm.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Resources for Resisting Federal Repression

Since June of 2020, activists have been subjected to an increasingly aggressive crackdown on protests by federal law enforcement. The federal response to the movement for Black Lives has included federal criminal charges for activists, door knocks by federal law enforcement agents, and increased use of federal troops to violently police protests.

The NLG National Office is releasing this resource page for activists who are resisting federal repression. It includes a link to our emergency hotline numbers, as well as our library of Know-Your-Rights materials, our recent federal repression webinar, and a list of some of our recommended resources for activists. We will continue to update this page.

Please visit the NLG Mass Defense Program page for general protest-related legal support hotlines run by NLG chapters.

Emergency Hotlines

If you are contacted by federal law enforcement you should exercise all of your rights. It is always advisable to speak to an attorney before responding to federal authorities.

State and Local Hotlines

If you have been contacted by the FBI or other federal law enforcement, in one of the following areas, you may be able to get help or information from one of these local NLG hotlines for:

- Portland, Oregon: (833) 680-1312

- San Francisco, California: (415) 285-1041 or fbi_hotline@nlgsf.org

- Seattle, Washington: (206) 658-7963

National Hotline

If you are located in an area with no hotline, you can call the following number:

Know Your Rights Materials

The NLG maintains a library of basic Know-Your-Rights guides.

- Know Your Rights During Covid-19

- You Have The Right To Remain Silent: A Know Your Rights Guide for Encounters with Law Enforcement

- Operation Backfire: For Environmental and Animal Rights Activists

WEBINAR: Federal Repression of Activists & Their Lawyers: Legal & Ethical Strategies to Defend Our Movements: presented by NLG-NYC and NLG National Office

We also recommend the following resources:

Center for Constitutional Rights

Civil Liberties Defense Center

- Grand Juries: Slideshow

Grand Jury Resistance Project

Katya Komisaruk

Movement for Black Lives Legal Resources

Tilted Scales Collective

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

By Julia Conley

—Common Dreams, September 30, 2022

https://www.commondreams.org/news/2022/09/30/time-take-streets-working-class-hold-enough-enough-rallies-across-

Demonstrators protest outside 10 Downing Street in London on September 5, 2022, against the U.K. government's handling of the cost of living crisis as one-in-three British households is predicted to face fuel poverty this winter amid surging energy prices. (Photo: Wiktor Szymanowicz/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

Weeks of economic justice rallies organized by the Enough Is Enough campaign across the United Kingdom over the past six weeks have been building to a National Day of Action, set to take place Saturday in more than four dozen cities and towns as hundreds of thousands of people protest the country's cost-of-living crisis.

The campaign, whose roots lie in the trade union and tenants' rights movements, has outlined five specific demands of the U.K. government as renters have seen their average monthly housing costs skyrocket by 11% on average since last year and household energy bills approaching $4,000 (£3,582) per year.

At rallies this weekend in London, Liverpool, Glasgow, and dozens of other cities, the grassroots campaign will demand a higher minimum wage and pay that keeps up with inflation, lower energy bills, an end to food insecurity and food poverty through universal school lunches and other assistance, affordable housing for all, and new taxes for the wealthiest Britons.

"The people need to be out in the streets and demanding change from this government, and if necessary, a change of government entirely," said Mick Lynch, general secretary of the National Union of Rail, Maritime, and Transport Workers (RMT), in a TV interview Friday, as he noted that top executives in the rail industry are expected to gain up to £60,000 ($67,000) from the "mini-budget" introduced by the Conservative government last week.

While millionaires stand to benefit from the plan, the Liberal Democrats released research last week showing some of the U.K.'s lowest earners, including nurses and teachers who are starting their careers, will see their tax bills rise.

"Does a CEO need an extra zero at the end of their salary—or should nurses, posties, and teachers be able to heat their homes?" asked comedian and economic justice advocate Rob Delaney, who will appear at one of Saturday's rallies in London.

Meanwhile, the U.K.'s heavy reliance on gas to heat homes has caused energy prices to soar, and Enough Is Enough organizers say a price cap of £2,500, announced this week, is insufficient to help struggling households.

"We need to revert to pre-April levels, instead of using taxpayers' money to bail out energy companies who are making record profits," Laura Dickinson, who is organizing rallies planned for Saturday in northern England, told Vice.

The protests are being coordinated with labor strikes organized by unions including RMT. The unions are demanding higher pay to reflect the rising cost of living.

With an estimated 700,000 members of the Enough Is Enough campaign, organizers are expecting a huge turnout to join the 200,000 workers who will be on picket lines.

Since mid-August, thousands of people have attended rallies across the country where they've listened to the personal stories of workers who have had to take second jobs and regularly spend their entire monthly wages on housing, food, and fuel.

"Sometimes I can be just too angry about how they treat us, but I think they want us to be tired," said a Communication Workers Union member named Emma at a gathering in the town of Luton, England earlier this month. "I think they want us too weak to fight, but we owe it to ourselves and those that are too weak to stand up. We need to tell them that they're not alone and we're in this together."

Progressive members of Parliament have expressed their support for the National Day of Action.

"The Tories are waging war on our communities while lining the pockets of their class," said MP Zarah Sultana at a rally in Liverpool this week. "It's time to fight back."

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

The New York Times analyzed dozens of videos circulating online for insights about what is propelling the demonstrations, and how women are leading the movement.

By Nilo Tabrizy and Haley Willis, Oct. 4, 2022

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/04/world/asia/iran-protest-video-analysis.html

Screenshot

Protests erupted in more than 80 cities across Iran following the death of Mahsa Amini, known by her first Kurdish surname Jina, after her detention by the morality police under the so-called hijab law. Footage of the demonstrations posted to social media has become one of the primary windows into what is happening on the ground and revealed what is different about this latest show of resistance inside Iran.

The New York Times analyzed dozens of videos and spoke with experts who have followed the country’s protest movements to understand what insights the often blurry, pixelated footage contains about what is propelling the demonstrations.

Attacking Symbols of the State

Now in their third week, protests have continued even as dozens of people have been killed. Many of the videos appeared on social media during the first week of the protests, before Iran’s government began limiting internet access in an effort to silence dissent.

Multiple videos show a consistent theme of protesters attacking structures and symbols that represent Iran’s government, in some cases setting fire to municipal structures. In the northern city of Amol, demonstrators set fires in the complex of the governorate building, and elsewhere took down portraits of the supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and the founding leader of the Islamic Republic, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

Reza H. Akbari, a program manager for the Middle East and North Africa at the Institute for War and Peace Reporting, said that targeting state symbols is a response in part to the government’s failure to engage with civil society. Following a national uprising in 2009, the government weakened grass roots organizations, like labor unions and student groups, which were outlets for citizens to discuss their grievances and engage with policymakers. That segment of society, he said, “does not have that many options left than to resort to violent attacks on security and administrative buildings.”

He added that while the targeting of such buildings isn’t new, the widespread nature of the attacks is noteworthy.

Iran’s security forces have a history of using violence and brutality to suppress dissent. In many instances, authorities have shot protesters on the streets. Amnesty International has said that at least 52 people have been killed since the start of the protests, noting that the death toll is likely much higher. Videos capture men in military fatigues using Kalashnikov-type assault rifles in protest areas, as well as the sound of sustained bursts of automatic rifle fire breaking up crowds.

One of the latest examples surfaced online Friday, from protests in the southeastern city of Zahedan. Automatic rifle fire can be heard disrupting prayers at a nearby local mosque, and one video shows a number of apparently injured and bleeding men being tended to outside.

In the past, the families of those killed by security forces have been intimidated by the authorities into keeping quiet. But this latest round of protests has seen videos of funeral services uploaded online showing displays of public mourning, such as a woman cutting her hair over a coffin.

Narges Bajoghli, an assistant professor of Middle East Studies at Johns Hopkins University, noted how similar public mourning rituals for those killed in the 1979 Islamic Revolution were key to support for the revolution’s success. Now, spreading widely online, these scenes help boost antigovernment sentiment, she said.

“They’re grieving over their children being so senselessly murdered,” she said. “And that is now circulating online among Iranians. And so it creates even more grief, more rage but also more solidarity.”

Women in the Lead

Across Iran, videos show that women are most often at the forefront of the recent demonstrations, rallying crowds of both women and men by engaging in symbolic acts of defiance. One of these acts, women burning their hijabs, has become a dominant theme of the protests, representing both solidarity with Ms. Amini and pushback against the mandatory wearing of hijabs, one of the most visible symbols of the repression of women under the Islamic Republic.

The large number of women leading the protests “in so many of the videos that we see, we saw that in 2009, too,” said Dr. Bajoghli, referring to the 2009 uprising in Iran. “But here the numbers seem to be much greater.”

Mr. Akbari of the Institute for War and Peace Reporting, pointed to videos showing women cutting off their hair in public, or on social media, as unique to the current demonstrations. “It’s a very powerful gesture of Iranian women almost sarcastically and bitterly stating that: ‘If it’s the hair that is bothering you — if it’s the hair you want — here you go,’” he said.

Beyond the now viral clips of hijab burning and hair cutting, footage of the demonstrations also reveals new ways in which common protest language has become centered on women. Dr. Bajoghli noted the adaptation of a well-known chant, used in past protest movements, from “I will defend my brother” to “I will defend my sister.”

Another chant — originating with Kurdish female fighters and the Kurdish feminist movement — is now heard in videos from nearly every major protest across the country: “Women. Life. Freedom.”

Videos also show women in direct, physical confrontation with security forces, not only putting themselves at the forefront of demonstrations, but physically pushing back against the police when challenged.

“The big willingness to put your body on the line and to say, ‘I’m coming at you and I’m going to fight you with my own body’ — that I haven’t seen,” said Dr. Bajoghli. “And that, I think, is what is causing this to be so difficult for the state to deal with.”

Widespread Solidarity

The Times’ analysis of videos posted to social media also reveals how the current protests are widespread geographically, ethnically and among various social classes.

“We haven’t seen national protests at this level and with this many folks that we would traditionally categorize as the middle class since 2009,” said Dr. Bajoghli. “And so now we’re seeing it again, but we’re seeing it in a new generation that’s doing it, and we’re seeing it link up with smaller towns across the country and with people who are not from the middle class.”

Footage has emerged from some of the country’s most religiously conservative cities like Qom, and its southern islands, as well as ethnic minority areas like Oshnavieh, which is home to Kurdish-Iranians.

Experts also found it noteworthy that the nationwide protests were sparked by the death of a woman from the Kurdish ethnic minority — signaling a new solidarity between disparate regions of the country. In one video from Iran’s capital, Tehran, the Kurdish feminist chant: “Women, Life, Freedom” — is said in its original Kurdish language, and not translated into Persian, the primary language used throughout most of the country.

“The Kurdish areas in the country have actually witnessed a lot of protests and there’s been a lot of tension there,” said Mr. Akbari. “But I think what’s powerful with this cycle is how the issue is a crosscutting matter for all walks of life and all ethnic backgrounds in the country.”

Protests erupted in more than 80 cities across Iran following the death of Mahsa Amini, known by her first Kurdish surname Jina, after her detention by the morality police under the so-called hijab law. Footage of the demonstrations posted to social media has become one of the primary windows into what is happening on the ground and revealed what is different about this latest show of resistance inside Iran.

The New York Times analyzed dozens of videos and spoke with experts who have followed the country’s protest movements to understand what insights the often blurry, pixelated footage contains about what is propelling the demonstrations.

Attacking Symbols of the State

Now in their third week, protests have continued even as dozens of people have been killed. Many of the videos appeared on social media during the first week of the protests, before Iran’s government began limiting internet access in an effort to silence dissent.

Multiple videos show a consistent theme of protesters attacking structures and symbols that represent Iran’s government, in some cases setting fire to municipal structures. In the northern city of Amol, demonstrators set fires in the complex of the governorate building, and elsewhere took down portraits of the supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and the founding leader of the Islamic Republic, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

Reza H. Akbari, a program manager for the Middle East and North Africa at the Institute for War and Peace Reporting, said that targeting state symbols is a response in part to the government’s failure to engage with civil society. Following a national uprising in 2009, the government weakened grass roots organizations, like labor unions and student groups, which were outlets for citizens to discuss their grievances and engage with policymakers. That segment of society, he said, “does not have that many options left than to resort to violent attacks on security and administrative buildings.”

He added that while the targeting of such buildings isn’t new, the widespread nature of the attacks is noteworthy.

Iran’s security forces have a history of using violence and brutality to suppress dissent. In many instances, authorities have shot protesters on the streets. Amnesty International has said that at least 52 people have been killed since the start of the protests, noting that the death toll is likely much higher. Videos capture men in military fatigues using Kalashnikov-type assault rifles in protest areas, as well as the sound of sustained bursts of automatic rifle fire breaking up crowds.

One of the latest examples surfaced online Friday, from protests in the southeastern city of Zahedan. Automatic rifle fire can be heard disrupting prayers at a nearby local mosque, and one video shows a number of apparently injured and bleeding men being tended to outside.

In the past, the families of those killed by security forces have been intimidated by the authorities into keeping quiet. But this latest round of protests has seen videos of funeral services uploaded online showing displays of public mourning, such as a woman cutting her hair over a coffin.

Narges Bajoghli, an assistant professor of Middle East Studies at Johns Hopkins University, noted how similar public mourning rituals for those killed in the 1979 Islamic Revolution were key to support for the revolution’s success. Now, spreading widely online, these scenes help boost antigovernment sentiment, she said.

“They’re grieving over their children being so senselessly murdered,” she said. “And that is now circulating online among Iranians. And so it creates even more grief, more rage but also more solidarity.”

Women in the Lead

Across Iran, videos show that women are most often at the forefront of the recent demonstrations, rallying crowds of both women and men by engaging in symbolic acts of defiance. One of these acts, women burning their hijabs, has become a dominant theme of the protests, representing both solidarity with Ms. Amini and pushback against the mandatory wearing of hijabs, one of the most visible symbols of the repression of women under the Islamic Republic.

The large number of women leading the protests “in so many of the videos that we see, we saw that in 2009, too,” said Dr. Bajoghli, referring to the 2009 uprising in Iran. “But here the numbers seem to be much greater.”

Mr. Akbari of the Institute for War and Peace Reporting, pointed to videos showing women cutting off their hair in public, or on social media, as unique to the current demonstrations. “It’s a very powerful gesture of Iranian women almost sarcastically and bitterly stating that: ‘If it’s the hair that is bothering you — if it’s the hair you want — here you go,’” he said.

Beyond the now viral clips of hijab burning and hair cutting, footage of the demonstrations also reveals new ways in which common protest language has become centered on women. Dr. Bajoghli noted the adaptation of a well-known chant, used in past protest movements, from “I will defend my brother” to “I will defend my sister.”

Another chant — originating with Kurdish female fighters and the Kurdish feminist movement — is now heard in videos from nearly every major protest across the country: “Women. Life. Freedom.”

Videos also show women in direct, physical confrontation with security forces, not only putting themselves at the forefront of demonstrations, but physically pushing back against the police when challenged.

“The big willingness to put your body on the line and to say, ‘I’m coming at you and I’m going to fight you with my own body’ — that I haven’t seen,” said Dr. Bajoghli. “And that, I think, is what is causing this to be so difficult for the state to deal with.”

Widespread Solidarity

The Times’ analysis of videos posted to social media also reveals how the current protests are widespread geographically, ethnically and among various social classes.

“We haven’t seen national protests at this level and with this many folks that we would traditionally categorize as the middle class since 2009,” said Dr. Bajoghli. “And so now we’re seeing it again, but we’re seeing it in a new generation that’s doing it, and we’re seeing it link up with smaller towns across the country and with people who are not from the middle class.”

Footage has emerged from some of the country’s most religiously conservative cities like Qom, and its southern islands, as well as ethnic minority areas like Oshnavieh, which is home to Kurdish-Iranians.

Experts also found it noteworthy that the nationwide protests were sparked by the death of a woman from the Kurdish ethnic minority — signaling a new solidarity between disparate regions of the country. In one video from Iran’s capital, Tehran, the Kurdish feminist chant: “Women, Life, Freedom” — is said in its original Kurdish language, and not translated into Persian, the primary language used throughout most of the country.

“The Kurdish areas in the country have actually witnessed a lot of protests and there’s been a lot of tension there,” said Mr. Akbari. “But I think what’s powerful with this cycle is how the issue is a crosscutting matter for all walks of life and all ethnic backgrounds in the country.”

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Officials say Taiwan needs to become a “porcupine” with enough weapons to hold out if the Chinese military blockades and invades it, even if Washington decides to send troops.

By Edward Wong and John Ismay, Oct. 5, 2022

“The United States and its allies have prioritized sending weapons to Ukraine, which is reducing those countries’ stockpiles, and arms makers are reluctant to open new production lines without a steady stream of long-term orders. …Jens Stoltenberg, secretary general of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, said in an interview that weapons makers want to see predictability in orders before committing to building up production. Arms directors from the United States and more than 40 other nations met last week in Brussels to discuss long-term supply and production issues."

”https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/05/us/politics/taiwan-biden-weapons-china.html

Taiwanese military exercises in July. The United States has approved several weapons packages for the island. Credit...Lam Yik Fei for The New York Times

WASHINGTON — American officials are intensifying efforts to build a giant stockpile of weapons in Taiwan after studying recent naval and air force exercises by the Chinese military around the island, according to current and former officials.

The exercises showed that China would probably blockade the island as a prelude to any attempted invasion, and Taiwan would have to hold out on its own until the United States or other nations intervened, if they decided to do that, the current and former officials say.

But the effort to transform Taiwan into a weapons depot faces challenges. The United States and its allies have prioritized sending weapons to Ukraine, which is reducing those countries’ stockpiles, and arms makers are reluctant to open new production lines without a steady stream of long-term orders.

And it is unclear how China might respond if the United States accelerates shipments of weapons to Taiwan, a democratic, self-governing island that Beijing claims is Chinese territory.

U.S. officials are determining the quantity and types of weapons sold to Taiwan by quietly telling Taiwanese officials and American arms makers that they will reject orders for some large systems in favor of a greater number of smaller, more mobile weapons. The Biden administration announced on Sept. 2 that it had approved its sixth weapons package for Taiwan — a $1.1 billion sale that includes 60 Harpoon coastal antiship missiles. U.S. officials are also discussing how to streamline the sale-and-delivery process.

President Biden said last month that the United States is “not encouraging” Taiwan’s independence, adding, “That’s their decision.” Since 1979, Washington has had a policy of reassuring Beijing that it does not support independence. But China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, said in a speech at the Asia Society last month that the United States was undermining that position “by repeated official exchanges and arms sales, including many offensive weapons.”

The People’s Liberation Army of China carried out exercises in August with naval ships and fighter jets in zones close to Taiwan. It also fired ballistic missiles into the waters off Taiwan’s coast, four of which went over the island, according to Japan.

The Chinese military acted after Nancy Pelosi, speaker of the House, visited Taiwan. But even before that, U.S. and Taiwanese officials had been more closely examining the potential for an invasion because Russia’s assault on Ukraine had made the possibility seem more real, though Chinese leaders have not explicitly stated a timeline for establishing rule over Taiwan.

The United States would not be able to resupply Taiwan as easily as Ukraine because of the lack of ground routes from neighboring countries. The goal now, officials say, is to ensure that Taiwan has enough arms to defend itself until help arrives. Mr. Biden said last month that U.S. troops would defend Taiwan if China were to carry out an “unprecedented attack” on the island — the fourth time he has stated that commitment and a shift from a preference for “strategic ambiguity” on Taiwan among U.S. presidents.

“Stockpiling in Taiwan is a very active point of discussion,” said Jacob Stokes, a fellow at the Center for a New American Security who advised Mr. Biden on Asia policy when he was vice president. “And if you have it, how do you harden it and how do you disperse it so Chinese missiles can’t destroy it?”

“The view is we need to lengthen the amount of time Taiwan can hold out on its own,” he added. “That’s how you avoid China picking the low-hanging fruit of its ‘fait accompli’ strategy — that they’ve won the day before we’ve gotten there, that is assuming we intervene.”

U.S. officials increasingly emphasize Taiwan’s need for smaller, mobile weapons that can be lethal against Chinese warships and jets while being able to evade attacks, which is central to so-called asymmetric warfare.

“Shoot-and-scoot” types of armaments are popular with the Ukrainian military, which has used shoulder-fired Javelin and NLAW antitank guided missiles and Stinger antiaircraft missiles effectively against Russian forces. Recently, the Ukrainians have pummeled Russian troops with mobile American-made rocket launchers known as HIMARS.

To transform Taiwan into a “porcupine,” an entity bristling with armaments that would be costly to attack, American officials have been trying to steer Taiwanese counterparts toward ordering more of those weapons and fewer systems for a conventional ground war like M1 Abrams tanks.

Pentagon and State Department officials have also been speaking regularly about these issues since March with American arms companies, including at an industry conference on Taiwan this week in Richmond, Va. Jedidiah Royal, a Defense Department official, said in a speech there that the Pentagon was helping Taiwan build out systems for “an island defense against an aggressor with conventional overmatch.”

In a recent article, James Timbie, a former State Department official, and James O. Ellis Jr., a retired U.S. Navy admiral, said Taiwan needs “a large number of small things” for distributed defense, and that some of Taiwan’s recent purchases from the United States, including Harpoon and Stinger missiles, fit that bill. Taiwan also produces its own deterrent weapons, including minelayer ships, air defense missile systems and antiship cruise missiles.

They said Taiwan needs to shift resources away from “expensive, high-profile conventional systems” that China can easily destroy in an initial attack, though some of those systems, notably F-16 jets, are useful for countering ongoing Chinese fighter jet and ship activities in “gray zone” airspace and waters. The authors also wrote that “the effective defense of Taiwan” will require stockpiling ammunition, fuel and other supplies, as well as strategic reserves of energy and food.

Officials in the administration of Tsai Ing-wen, the president of Taiwan, say they recognize the need to stockpile smaller weapons but point out that there are significant lags between orders and shipments.

“I think we’re moving in a high degree of consensus in terms of our priorities on the asymmetric strategy, but the speed does have to be accelerated,” Bi-khim Hsiao, the de facto Taiwanese ambassador in Washington, said in an interview.

Some American lawmakers have called for faster and more robust deliveries. Several senior senators are trying to push through the proposed Taiwan Policy Act, which would provide $6.5 billion in security assistance to Taiwan over the next four years and mandate treating the island as if it were a “major non-NATO ally.”

But Jens Stoltenberg, secretary general of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, said in an interview that weapons makers want to see predictability in orders before committing to building up production. Arms directors from the United States and more than 40 other nations met last week in Brussels to discuss long-term supply and production issues.

If China decides to establish a naval blockade around Taiwan, American officials would probably study which avenue of resupplying Taiwan — by sea or by air — would offer the least likelihood of bringing Chinese and American ships, aircraft and submarines into direct conflict.

One proposition would involve sending U.S. cargo planes with supplies from bases in Japan and Guam to Taiwan’s east coast. That way, any Chinese fighters trying to shoot them down would have to fly over Taiwan and risk being downed by Taiwanese warplanes.

“The sheer amount of materiel that would likely be needed in case of war is formidable, and getting them through would be difficult, though may be doable,” said Eric Wertheim, a defense consultant and author of “The Naval Institute Guide to Combat Fleets of the World.” “The question is: How much risk is China and the White House willing to take in terms of enforcing or breaking through a blockade, respectively, and can it be sustained?”

China has probably studied the strategic failure of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, he said, and the United States should continue to send the kinds of arms to Taiwan that will make either an amphibious invasion or an attack with long-range weapons much more difficult for China.

“The Chinese naval officers I’ve spoken to in years past have said they fear the humiliation that would result from any kind of failure, and this of course has the effect of them being less likely to take action if there is an increased risk of failure,” Mr. Wertheim said. “In essence, the success the Ukrainians are having is a message to the Chinese.”

Officials in the Biden administration are trying to gauge what moves would deter China without actually provoking greater military action.

Jessica Chen Weiss, a professor of government at Cornell University who worked on China policy this past year in the State Department, wrote on Twitter that Mr. Biden’s recent remarks committing U.S. troops to defending Taiwan were “dangerous.” She said in an interview that pursuing the porcupine strategy enhances deterrence but that taking what she deems symbolic steps on Taiwan’s diplomatic status does not.

“The U.S. has to make clear that the U.S. doesn’t have a strategic interest in having Taiwan being permanently separated from mainland China,” she said.

But other former U.S. officials praise Mr. Biden’s forceful statements, saying greater “strategic clarity” bolsters deterrence.

“President Biden has said now four times that we would defend Taiwan, but each time he says it someone walks it back,” said Harry B. Harris Jr., a retired admiral who served as commander of U.S. Pacific Command and ambassador to South Korea. “And I think that makes us as a nation look weak because who’s running this show? I mean, is it the president or is it his advisers?

“So maybe we should take him at his word,” Admiral Harris added. “Maybe he is serious about defending Taiwan.”

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Kevin Cooper is an innocent man on San Quentin’s Death Row in California. He continues to struggle for exoneration and to abolish the death penalty in the whole U.S. Learn more about his case at: www.kevincooper.org

Write to:

Kevin Cooper #C-65304 4-EB-82

San Quentin State Prison

San Quentin, CA 94974

When I was in grade school, back in the 1960s, and I was uneducated, I was sent to school to be educated on the truth in every level of life. This included the discovery of this land, and its founding as the United States.

I believed, or thought, that I was not sent to grade school to be lied to by the very teachers who were supposed to educate me with the truth.

One of the lies that I learned way back then, as did all the other children who went to school at the same time as I did, as well as all the other generations of children who went to grade school before my generation, and after, is that Christopher Columbus discovered America.

We did not learn the truth, that before he and his crew of homicidal maniacs set sail for the continent of Asia, the country of India, that Columbus had participated in one of the greatest crimes in the history of the world—that he took part in the trans-Atlantic slave trade in his home country of Portugal. Nor did we know of his writings about the first people he met when he accidentally landed in what we now call the Americas. He called the human beings he saw Indians, because he mistakenly believed that he had landed in the country of India

He wrote, according to the late historian Howard Zinn, the following upon seeing the indigenous people he first encountered:

“They...brought us parrots and balls of cotton and spears and many other things, which they exchanged for glass beads and hawk’s bells. They willingly traded everything they owned...They were well built, with good bodies and handsome features...They do not bear arms, and they do not know them, for I showed them a sword, they took it by the edge and cut themselves out of ignorance. They have no iron. Their spears are made of cane...They would make fine servants...with 50 men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.”

That is exactly what Columbus, and his men did, and the rest is a tortured history. But we did not learn this truth in school from our teachers. And if certain politicians and certain states have their way, this and other truths will not be taught by any teacher to any student.

So, we cannot forget, nor can we ignore what happened in the past and act like it never happened, because in truth, it did really happen. Overtime, these truths and others have helped to educate the masses about what exactly Christopher Columbus was, and what his real legacy is. And all this happened to those indigenous people at that time in history because they—Arawak men and women, naked, tawny, and full of wonder, emerge from their villages onto the island’s beaches and swam out to get a closer look at the strange big boat. When Columbus and his sailors came ashore, carrying swords, speaking oddly, the Arawaks ran to greet them—brought them food, water, gifts—and for all these acts of humanity they had genocide committed upon them. So, we ask, who are the human people, and who are the inhuman—who's really the good and who's really the evil—tell the truth.

Respect and support Indigenous People’s Day.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

By John McWhorter, Opinion Writer, Oct. 7, 2022

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/07/opinion/black-english-testing.html

Delcan and Co.

It can be hard not to notice that a suspiciously large number of children, of seemingly normal human linguistic capacity, are officially designated as language impaired. In 2019, two researchers set out to determine just how common this phenomenon is. Examining nationwide data, they found that each year, 14 percent of states overrepresent the number of Black children with speech and language impairments.

Just what does “language impaired” mean, though? Much of the reason this diagnosis is so disproportionate among this group and has been for decades is that too many people who are supposedly trained in assessing children’s language skills aren’t actually taught much about how human language works. And it affects the lives of Black kids dramatically.

The reason for that overrepresentation is that most Black children grow up code switching between Black English and standard English. There is nothing exotic about this; legions of people worldwide live between two dialects of a language, one casual and one formal, and barely think about it. Many Germans, Italians, Chinese people, South Asians and Southeast Asians and most Arabs are accustomed to speaking different varieties of language according to different forms of social interaction. So, too, are Black Americans. Black children, along the typical lines of bidialectal contexts like these, are much more comfortable with the casual variety of Black speech, only faintly aware that in formal settings there is a standard way of speaking that is considered more appropriate. Black English grammar is often assumed to be slang and mistakes. But it’s actually just an alternate, rather than degraded, form of English compared to the standard variety.