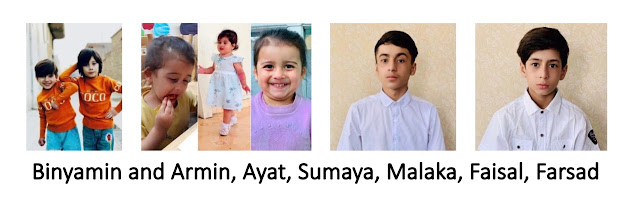

The Ahmadi Family Drone Massacre, August 29, 2021…..We will not forget

United in Action to STOP KILLER DRONES:

SHUT DOWN CREECH! Spring Action, 2022

March 26 - April 2—Saturday to Saturday

Co-sponsored by CODEPINK and Veterans For Peace

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

To: U.S. Senate, U.S. House of Representatives

End Legal Slavery in U.S. Prisons

Sign Petition at:

https://diy.rootsaction.org/petitions/end-legal-slavery-in-u-s-prisons

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

On the anniversary of the 26th of July Movement’s founding, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research launches the online exhibition, Let Cuba Live. 80 artists from 19 countries – including notable cartoonists and designers from Cuba – submitted over 100 works in defense of the Cuban Revolution. Together, the exhibition is a visual call for the end to the decades-long US-imposed blockade, whose effects have only deepened during the pandemic. The intentional blocking of remittances and Cuba’s use of global financial institutions have prevented essential food and medicine from entering the country. Together, the images in this exhibition demand: #UnblockCuba #LetCubaLive

Please contact art@thetricontinental.org if you are interested in organising a local exhibition of the exhibition.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Rashid just called with the news that he has been moved back to Virginia. His property is already there, and he will get to claim the most important items tomorrow. He is at a "medium security" level and is in general population. Basically, good news.

He asked me to convey his appreciation to everyone who wrote or called in his support during the time he was in Ohio.

His new address is:

Kevin Rashid Johnson #1007485

Nottoway Correctional Center

2892 Schutt Road

Burkeville, VA 23922

www.rashidmod.com

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Freedom for Major Tillery! End his Life Imprisonment!

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

Contact: Governor's Press Office

Friday, May 28, 2021

(916) 445-4571

Governor Newsom Announces Clemency Actions, Signs Executive Order for Independent Investigation of Kevin Cooper Case

SACRAMENTO – Governor Gavin Newsom today announced that he has granted 14 pardons, 13 commutations and 8 medical reprieves. In addition, the Governor signed an executive order to launch an independent investigation of death row inmate Kevin Cooper’s case as part of the evaluation of Cooper’s application for clemency.

The investigation will review trial and appellate records in the case, the facts underlying the conviction and all available evidence, including the results of the recently conducted DNA tests previously ordered by the Governor to examine additional evidence in the case using the latest, most scientifically reliable forensic testing.

The text of the Governor’s executive order can be found here:

https://www.gov.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/5.28.21-EO-N-06-21.pdf

The California Constitution gives the Governor the authority to grant executive clemency in the form of a pardon, commutation or reprieve. These clemency grants recognize the applicants’ subsequent efforts in self-development or the existence of a medical exigency. They do not forgive or minimize the harm caused.

The Governor regards clemency as an important part of the criminal justice system that can incentivize accountability and rehabilitation, increase public safety by removing counterproductive barriers to successful reentry, correct unjust results in the legal system and address the health needs of incarcerated people with high medical risks.

A pardon may remove counterproductive barriers to employment and public service, restore civic rights and responsibilities and prevent unjust collateral consequences of conviction, such as deportation and permanent family separation. A pardon does not expunge or erase a conviction.

A commutation modifies a sentence, making an incarcerated person eligible for an earlier release or allowing them to go before the Board of Parole Hearings for a hearing at which Parole Commissioners determine whether the individual is suitable for release.

A reprieve allows individuals classified by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation as high medical risk to serve their sentences in appropriate alternative placements in the community consistent with public health and public safety.

The Governor weighs numerous factors in his review of clemency applications, including an applicant’s self-development and conduct since the offense, whether the grant is consistent with public safety and in the interest of justice, and the impact of a grant on the community, including crime victims and survivors.

While in office, Governor Newsom has granted a total of 86 pardons, 92 commutations and 28 reprieves.

The Governor’s Office encourages victims, survivors, and witnesses to register with CDCR’s Office of Victims and Survivors Rights and Services to receive information about an incarcerated person’s status. For general Information about victim services, to learn about victim-offender dialogues, or to register or update a registration confidentially, please visit:

www.cdcr.ca.gov/Victim_Services/ or call 1-877-256-6877 (toll free).

Copies of the gubernatorial clemency certificates announced today can be found here:

https://www.gov.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/5.28.21-Clemency-certs.pdf

Additional information on executive clemency can be found here:

https://www.gov.ca.gov/clemency/

###

Mumia Abu Jamal Appeal Denied!

https://mobilization4mumia.com

We regret to share with you some alarming news on the continued case of Political Prisoner Mumia Abu Jamal

PHILADELPHIA (KYW Newsradio)—The Pennsylvania Superior Court has challenged Mumia Abu-Jamal’s latest effort for an overturned conviction and new trial—nearly 40 years after he was convicted of killing Philadelphia Police Officer Daniel Faulkner.

The high court said Abu-Jamal’s appeal was untimely, adding that the lower court shouldn’t have reinstated any part of his appeal because it lacked jurisdiction.

This fifth appeal attempt—filed in 2016—was based on a federal ruling involving former Philadelphia District Attorney Ron Castille, who later became a state Supreme Court justice and ruled on a death penalty appeal. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled Castille had an “unconstitutional risk of bias” as the district attorney.

ABU-JAMAL’S ATTORNEYS ARGUED TO A PHILADELPHIA JUDGE IN 2018 THAT CASTILLE WAS ALSO THE DISTRICT ATTORNEY WHEN ABU-JAMAL WAS CONVICTED, AND A STATE SUPREME COURT JUDGE WHEN HE APPEALED.

And, they pointed to a letter Castille penned to the governor in 1990, urging the death penalty be used to send a “clear and dramatic message to all police killers that the death penalty in Pennsylvania actually means something.”

The Pennsylvania Superior Court concluded that “the 1990 letter cannot create a reasonable inference that Justice Castille had a personal interest in the outcome of the litigation,” court documents say. “There is no evidence that Castille had ever personally participated in the prosecution of Abu-Jamal.

“The 1990 letter is not evidence of prior prosecutorial participation. It is evidence that while acting as an advocate, District Attorney Castille took a policy position to advance completion of the appellate process for convicted murderers: ‘I very strongly urge you immediately to issue death warrants in each and every one of these cases. Only such action by you will cause these cases to move forward in a legally appropriate manner.’ He was not arguing that the law should be changed or should be ignored. Rather, he simply took a position to facilitate collateral review of death sentences which was subscribed to by many prosecutors at the time.” But, the state Superior Court noted, Castille didn’t list Abu-Jamal, and they say Abu-Jamal didn’t file a new petition, using the letter as an argument, in time.

“Further,” the decision reads, “the 1990 letter was dated June 15th. At that time, Abu-Jamal’s direct appeal was still pending before the Supreme Court of the United States. … As such, Abu-Jamal was not even in the class of litigants that District Attorney Castille was referencing in the letter. The 1990 letter therefore cannot create a reasonable inference that Justice Castille was personally biased against Abu-Jamal.”

RELATED

Pa. Supreme Court denies widow’s appeal to remove Philly DA from Abu-Jamal case

Abu Jamal was convicted by a jury of first-degree murder of Faulkner in 1982. Over the past four decades, five of his appeals have been quashed.

In 1989, the state’s highest court affirmed Abu-Jamal’s death penalty conviction, and in 2012, he was re-sentenced to life in prison.

Abu-Jamal, 66, remains in prison. He can appeal to the state Supreme Court, or he can file a new appeal.

KYW Newsradio reached out to Abu-Jamal’s attorneys for comment. They shared this statement in full:

“Today, the Superior Court concluded that it lacked jurisdiction to consider issues raised by Mr. Abu-Jamal in prior appeals. Two years ago, the Court of Common Pleas ordered reconsideration of these appeals finding evidence of an appearance of judicial bias when the appeals were first decided. We are disappointed in the Superior Court’s decision and are considering our next steps.

“While this case was pending in the Superior Court, the Commonwealth revealed, for the first time, previously undisclosed evidence related to Mr. Abu-Jamal’s case. That evidence includes a letter indicating that the Commonwealth promised its principal witness against Mr. Abu-Jamal money in connection with his testimony. In today’s decision, the Superior Court made clear that it was not adjudicating the issues raised by this new evidence. This new evidence is critical to any fair determination of the issues raised in this case, and we look forward to presenting it in court.”

https://www.audacy.com/kywnewsradio/news/local/pennsylvania-superior-court-rejects-mumia-abu-jamal-appeal-ron-castille

Questions and comments may be sent to: info@freedomarchives.org

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Sign our petition urging President Biden to grant clemency to Leonard Peltier.

https://www.freeleonardpeltier.com/petition

Thank you!

Email: contact@whoisleonardpeltier.info

Address: 116 W. Osborne Ave. Tampa, Florida 33603

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Resources for Resisting Federal Repression

Since June of 2020, activists have been subjected to an increasingly aggressive crackdown on protests by federal law enforcement. The federal response to the movement for Black Lives has included federal criminal charges for activists, door knocks by federal law enforcement agents, and increased use of federal troops to violently police protests.

The NLG National Office is releasing this resource page for activists who are resisting federal repression. It includes a link to our emergency hotline numbers, as well as our library of Know-Your-Rights materials, our recent federal repression webinar, and a list of some of our recommended resources for activists. We will continue to update this page.

Please visit the NLG Mass Defense Program page for general protest-related legal support hotlines run by NLG chapters.

Emergency Hotlines

If you are contacted by federal law enforcement you should exercise all of your rights. It is always advisable to speak to an attorney before responding to federal authorities.

State and Local Hotlines

If you have been contacted by the FBI or other federal law enforcement, in one of the following areas, you may be able to get help or information from one of these local NLG hotlines for:

- Portland, Oregon: (833) 680-1312

- San Francisco, California: (415) 285-1041 or fbi_hotline@nlgsf.org

- Seattle, Washington: (206) 658-7963

National Hotline

If you are located in an area with no hotline, you can call the following number:

Know Your Rights Materials

The NLG maintains a library of basic Know-Your-Rights guides.

- Know Your Rights During Covid-19

- You Have The Right To Remain Silent: A Know Your Rights Guide for Encounters with Law Enforcement

- Operation Backfire: For Environmental and Animal Rights Activists

WEBINAR: Federal Repression of Activists & Their Lawyers: Legal & Ethical Strategies to Defend Our Movements: presented by NLG-NYC and NLG National Office

We also recommend the following resources:

Center for Constitutional Rights

Civil Liberties Defense Center

- Grand Juries: Slideshow

Grand Jury Resistance Project

Katya Komisaruk

Movement for Black Lives Legal Resources

Tilted Scales Collective

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

George Floyd’s murder set in motion shock waves that touched almost every aspect of American society. But on the core issues of police violence and accountability, very little has changed.

By Tim Arango and Giulia Heyward, Dec. 24, 2021

“Since Mr. Floyd’s death in May of last year, 1,646 people have been killed by the police, or about three people per day on average, according to Mapping Police Violence, a nonprofit that tracks police killings.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/24/us/police-killings-accountability.html

A memorial in Minneapolis for victims of police violence. Credit...Joshua Rashaad McFadden for The New York Times

For the second time this year, a jury in Minneapolis has ruled against a former police officer for killing a Black man.

Like the conviction of Derek Chauvin for the murder of George Floyd, the verdict on Thursday against Kimberly Potter on two counts of manslaughter for the shooting death of Daunte Wright during a traffic stop represented an unusual decision to send a police officer to prison.

And yet, despite the two high-profile convictions in Minneapolis, a review of the data a year and a half after America’s summer of protest shows that accountability for officers who kill remains elusive and that the sheer numbers of police killings have remained steady at an alarming level.

The murder of Mr. Floyd on a Minneapolis street corner drew millions to the streets in protest and set off a national reassessment on race that touched almost every aspect of American life, from corporate boardrooms to sports nicknames. But on the core issues that set off the social unrest in the first place — police violence and accountability — very little has changed.

Since Mr. Floyd’s death in May of last year, 1,646 people have been killed by the police, or about three people per day on average, according to Mapping Police Violence, a nonprofit that tracks police killings. Although murder or manslaughter charges against officers have increased this year, criminal charges, much less convictions, remain exceptionally rare.

That underscores both the benefit of the doubt usually accorded law officers who are often making life-or-death decisions in a split second and the way the law and the power of police unions often protect officers, say activists and legal experts.

The convictions of both Mr. Chauvin, the former Minneapolis officer who was captured on an excruciating bystander video pinning Mr. Floyd to the ground for more than nine minutes as he gasped for air, and Ms. Potter strike some experts as tantalizing glimpses of a legal system in flux. Ms. Potter’s case, in particular, reflected the kind of split-second decision — she mistakenly used her gun instead of her Taser after Mr. Wright tried to flee an arrest — that jurors usually excuse even when something goes horribly wrong.

Chris Uggen, a sociology and law professor at the University of Minnesota, said that even though police killings remained prevalent, high-profile cases could still send a message to the police. “The probability of punishment is not zero,” he said. “So it moves the needle to some degree, and it can certainly affect the behaviors of police officers.”

But many experts are reluctant to read too much into a few isolated cases carried out in the glare of media scrutiny.

“Criminal trials are not designed to be instruments of change,” said Paul Butler, a professor at Georgetown University Law Center and a former prosecutor. “Criminal trials are about bringing individual wrongdoers to justice. So while there have been high-profile prosecutions of police officers for killing Black people, that doesn’t in and of itself lead to the kind of systemic reform that might reduce police violence.”

Philip M. Stinson, a criminal justice professor at Bowling Green State University in Ohio, who tracks police criminal charges and convictions, said Ms. Potter was the first female police officer convicted of a murder or manslaughter charge in an on-duty shooting since 2005. He said he believed that the number of deaths from excessive police force was higher than what was recorded and reflected in news coverage.

“Many police officers exhibit a fear of Black people,” he said. “Until we can address that, it is very difficult to bring about meaningful reforms.”

Gloria J. Browne-Marshall, a constitutional law professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York, said accountability also needed to be aimed at prosecutors who gave officers “carte blanche” for a century until the recent show of public outrage. Change is not likely to come soon, she said.

“In these individual cases, justice won in the end,” she said. “But there is a lot of work that still needs to be done.”

In fact, there has been no finding of fault against officers in many of the other recent high-profile police killings.

Less than three weeks after the murder of Mr. Floyd, an officer in Atlanta fatally shot a Black man named Rayshard Brooks, who was fleeing a Wendy’s parking lot after taking a Taser from the officer’s partner and firing it at him. The killing in Atlanta, like that of Mr. Floyd’s, was captured on bystander video and drew protesters, adding to the demands for justice and accountability over the number of African Americans killed by the police.

And about two months before Mr. Floyd’s murder, Breonna Taylor was killed in her Louisville apartment during a botched police raid that targeted an ex-boyfriend for alleged drug crimes. Her name, too, became familiar to millions of Americans.

Yet the officers involved in the Taylor case have largely been cleared, even as federal authorities continue to investigate. And in Atlanta, Mr. Brooks’s case stalled this summer as it was passed to a third prosecutor, who is starting the investigation all over again. The officer who shot Mr. Brooks has been charged with murder, but there is no timeline for a trial.

“We are taking a fresh look at it and starting from Day 1,” said Pete Skandalakis, the special prosecutor in Georgia who took over the case. He added that he could not predict when the case would see a courtroom.

That has left Mr. Brooks’s family wondering if they will ever see justice.

“I think we’re all just lost right now,” said L. Chris Stewart, a lawyer who represents the Brooks family. “We don’t know what to think or what’s going on.”

According to data kept by Mr. Stinson and a research team at Bowling Green, 21 officers this year have been charged with murder or manslaughter for an on-duty shooting — although five of the officers charged are for the same encounter, the killing in November 2020 of a 15-year-old boy who was a suspect in an armed robbery.

While this is an increase from the 16 officers charged in 2020, and the highest number since Mr. Stinson began compiling the data since 2005, it remains small next to the roughly 1,100 people killed by the police annually. (Just as the pace of killings since Mr. Floyd’s death has remained largely unchanged, racial disparities have also stayed the same. Black people are still two and a half to three times as likely as white people to be killed by a police officer, according to Mapping Police Violence.)

While Mr. Chauvin’s trial was underway in the spring, Mr. Wright’s death at the hands of Ms. Potter in Brooklyn Center, a Minneapolis suburb, set off new rounds of protests in the Twin Cities. And in the rest of America, new police killings continued apace, some of them piercing the national consciousness and adding to the names protesters shouted in the streets.

Among them were Adam Toledo, a 13-year-old Latino boy who was killed by a Chicago police officer after running down a dark alleyway with a gun. And in Columbus, Ohio, shortly before the jury reached a decision in the Chauvin trial, a 16-year-old Black girl named Ma’Khia Bryant was shot to death by an officer as she swung a knife at a young woman.

A state agency investigated Ma’Khia’s death and, in July, turned its findings over to local prosecutors in Franklin County. At the time, the state attorney general said he expected it to take prosecutors “several weeks” to make a charging decision, but a spokeswoman for G. Gary Tyack, the county’s top prosecutor, said the case was still under review five months later.

More recently, at a high school football game in a suburb of Pennsylvania this fall, police officers opened fire amid a crowd after they heard gunshots, killing an 8-year-old Black girl named Fanta Bility.

All of these cases remain under investigation, and no charges have been filed against the officers involved.

One of the reasons for Mr. Chauvin’s conviction was that the circumstances of the case differed so starkly from so many other cases in which officers were cleared by prosecutors or juries: There was no split-second decision made in an environment in which Mr. Chauvin could argue that his life, or those of other officers, was in danger.

In the trial of Ms. Potter, which played out in the same courtroom where Mr. Chauvin was tried, her defense lawyers said Ms. Potter acted reasonably in using force because she feared for the life of a fellow officer, a scenario more emblematic of a typical police killing case.

This time, that argument did not work.

Nicholas Bogel-Burroughs contributed reporting.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

The suspect was killed and a shot pierced a wall, fatally striking a 14-year-old in a dressing room during the confrontation at a clothing store, the police said.

By Michael Levenson, Published Dec. 23, 2021, Updated Dec. 24, 2021

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/23/us/girl-fatally-shot-police-los-angeles.html

After the shooting, officers found a heavy metal lock near the suspect but no gun. Credit...Ringo H.W. Chiu/Associated Press

A Los Angeles police officer opened fire on a man who was involved in an assault at a clothing store on Thursday, and one of the shots pierced a wall, killing a 14-year-old girl in a dressing room, the police said.

The shooting happened at a Burlington store in North Hollywood during the busy holiday shopping season after the police received reports at about 11:45 a.m. of an assault with a deadly weapon and possible shots fired, the police said. Some of the callers said they were hiding in the store, the police said.

When the officers arrived, they went upstairs and found a man who was assaulting a woman, the police said. The police opened fire, killing the man, whose name was not immediately released, the police said.

Officers found a heavy metal lock near the man but no gun, Dominic H. Choi, an assistant chief of the Los Angeles Police Department, said at a news conference.

A woman who had been assaulted was taken to the hospital with injuries to her head and arms, Chief Choi said. Her relationship to the suspect was not immediately known, he said.

As officers continued to search the store, they noticed a hole in the wall, Chief Choi said. Behind the wall, they found the 14-year-old girl who had been shot and killed in the dressing room.

The teenager had been in the dressing room with her mother, the Los Angeles Police chief, Michel R. Moore, told LAist.com, adding that the shooting was the “worst thing anyone can imagine.” The police did not immediately release the girl’s name.

Chief Choi described the encounter as a “tragic and unfortunate sequence of events” and said it remained under investigation. He said that the investigation had indicated that the girl had been fatally shot by the police.

“Preliminarily, we believe that round was an officer’s round,” he said.

He said investigators had not yet reviewed body-camera video or the store’s security-camera footage, although it appeared the dressing room had been in the officer’s line of fire.

“The dressing room was behind where the suspect was, in front of the officer,” Chief Choi said, adding: “You can’t see into the dressing rooms. It just looks like a straight wall of drywall.”

California’s attorney general, Rob Bonta, said the California Department of Justice was investigating the shooting.

Once the investigation has been completed, it will be turned over to the California Department of Justice’s Special Prosecutions Section for review, he said.

Burlington, which was formerly known as Burlington Coat Factory, said in a statement that it was supporting the authorities in their investigation.

“At Burlington, our hearts are heavy as a result of the tragic incident that occurred today at our North Hollywood, Calif., store,” the company said. “Our top priority is always the safety and well-being of our customers and associates.”

Azi Paybarah contributed reporting.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

The agreement’s national scope and its concessions to organizing go further than any previous settlement that the e-commerce giant has made.

By Karen Weise, Published Dec. 23, 2021, Updated Dec. 24, 2021

A labor activist and his son encouraging motorists to sign union authorization cards outside Amazon’s JFK8 distribution center on Staten Island in May. Credit...Dave Sanders for The New York Times

SEATTLE — Amazon, which faces mounting scrutiny over worker rights, agreed to let its warehouse employees more easily organize in the workplace as part of a nationwide settlement with the National Labor Relations Board this month.

Under the settlement, made final on Wednesday, Amazon said it would email past and current warehouse workers — likely more than one million people — with notifications of their rights and give them greater flexibility to organize in its buildings. The agreement also makes it easier and faster for the N.L.R.B., which investigates claims of unfair labor practices, to sue Amazon if it believes the company violated the terms.

Amazon has previously settled individual cases with the labor agency, but the new settlement’s national scope and its concessions to organizing go further than any previous agreement.

Because of Amazon’s sheer size — more than 750,000 people work in its operations in the United States alone — the agency said the settlement would reach one of the largest groups of workers in its history. The tech giant also agreed to terms that would let the N.L.R.B. bypass an administrative hearing process, a lengthy and cumbersome undertaking, if the agency found that the company had not abided by the settlement.

The agreement stemmed from six cases of Amazon workers who said the company limited their ability to organize colleagues. A copy was obtained by The New York Times.

It is a “big deal given the magnitude of the size of Amazon,” said Wilma B. Liebman, who was the chair of the N.L.R.B. under President Barack Obama.

Amazon, which has been on a hiring frenzy in the pandemic and is the nation’s second-largest private employer after Walmart, has faced increased labor pressure as its work force has soared to nearly 1.5 million globally. The company has become a leading example of a rising tide of worker organizing as the pandemic reshapes what employees expect from their employers.

This year, Amazon has grappled with organizing efforts at warehouses in Alabama and New York, and the International Brotherhood of Teamsters formally committed to support organizing at the company. Other companies, such as Starbucks, Kellogg and Deere & Company, have faced rising union activity as well.

Compounding the problem, Amazon is struggling to find enough employees to satiate its growth. The company was built on a model of high-turnover employment, which has now crashed into a phenomenon known as the Great Resignation, with workers in many industries quitting their jobs in search of a better deal for themselves.

Amazon has responded by raising wages and pledging to improve its workplace. It has said it would spend $4 billion to deal with labor shortages this quarter alone.

“This settlement agreement provides a crucial commitment from Amazon to millions of its workers across the United States that it will not interfere with their right to act collectively to improve their workplace by forming a union or taking other collective action,” Jennifer Abruzzo, the N.L.R.B.’s new general counsel appointed by President Biden, said in a statement on Thursday.

Amazon declined to comment. The company has said it supports workers’ rights to organize but believes employees are better served without a union.

Amazon and the labor agency have been in growing contact, and at times conflict. More than 75 cases alleging unfair labor practices have been brought against Amazon since the start of the pandemic, according to the N.L.R.B.’s database. Ms. Abruzzo has also issued several memos directing the agency’s staff to enforce labor laws against employers more aggressively.

Last month, the agency threw out the results of a failed, prominent union election at an Amazon warehouse in Alabama, saying the company had inappropriately interfered with the voting. The agency ordered another election. Amazon has not appealed the finding, though it can still do so.

Other employers, from beauty salons to retirement communities, have made nationwide settlements with the N.L.R.B. in the past when changing policies.

With the new settlement, Amazon agreed to change a policy that limited employee access to its facilities and notify employees that it had done so, as well as informing them of other labor rights. The settlement requires Amazon to post notices in all of its U.S. operations and on the employee app, called A to Z. Amazon must also email every person who has worked in its operations since March.

In past cases, Amazon explicitly said a settlement did not constitute an admission of wrongdoing. No similar language was included in the new settlement. In September, Ms. Abruzzo directed N.L.R.B. staff to accept these “non-admission clauses” only rarely.

The combination of terms, including the “unusual” commitment to email past and current employees, made Amazon’s settlement stand out, Ms. Liebman said, adding that other large employers were likely to take notice.

“It sends a signal that this general counsel is really serious about enforcing the law and what they will accept,” she said.

The six cases that led to Amazon’s settlement with the agency involved its workers in Chicago and Staten Island, N.Y. They had said Amazon prohibited them from being in areas like a break room or parking lot until within 15 minutes before or after their shifts, hampering any organizing.

One case was brought by Ted Miin, who works at an Amazon delivery station in Chicago. In an interview, Mr. Miin said a manager had told him, “It is more than 15 minutes past your shift, and you are not allowed to be here,” when he passed out newsletters at a protest in April.

“Co-workers were upset about being understaffed and overworked and staged a walkout,” he said, adding that a security guard also pressured him to leave the site while handing out leaflets.

In another case on Staten Island, Amazon threatened to call the police on an employee who handed out union literature on site, said Seth Goldstein, a lawyer who represents the company’s workers in Staten Island.

The right for workers to organize on-site during non-working time is well established, said Matthew Bodie, a former lawyer for the N.L.R.B. who teaches labor law at Saint Louis University.

“The fact that you can hang around and chat — that is prime, protected concerted activity periods, and the board has always been very protective of that,” he said.

Mr. Miin, who is part of an organizing group called Amazonians United Chicagoland, and other workers in Chicago reached a settlement with Amazon in the spring over the 15-minute rule at a different delivery station where they had worked last year. Two corporate employees also settled privately with Amazon in an agreement that included a nationwide notification of worker rights, but the agency does not police it.

Mr. Goldstein said he was “impressed” that the N.L.R.B. had pressed Amazon to agree to terms that would let the agency bypass its administrative hearing process, which happens before a judge and in which parties prepare arguments and present evidence, if it found the company had broken the agreement’s terms.

“They can get a court order to make Amazon obey federal labor law,” he said.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

By Meg Jacobs, Dec. 24, 2021

Dr. Jacobs teaches history and public affairs at Princeton and is the author of “Pocketbook Politics: Economic Citizenship in Twentieth-Century America.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/24/opinion/inflation-truman-biden-corporate-power.html

Álvaro Bernis

Since the Carter administration, monetary policy has been the chief tool presidents use to curb inflation, which has been on the rise: The Consumer Price Index rose by 6.8 percent in the year through November — the fastest pace since 1982. The Federal Reserve chair, Jerome Powell, has pivoted to a tighter monetary policy, announcing plans to taper the central bank’s bond purchases and raise interest rates next year.

Yet inflation doesn’t rise and ebb just because of monetary policy. It’s largely the result of choices businesses make. And history shows presidents have the power to stem inflation by taking on corporate power — if they choose.

While Franklin Roosevelt is best known for the New Deal expansion of the social safety net, he also protected Americans against wartime inflation. During World War II, his Office of Price Administration imposed price ceilings on three million businesses and more than eight million goods. The office also put caps on rents in 14 million dwellings occupied by 45 million residents and issued ration stamps for goods like meat to manage supply. According to Gallup polls, more than three-quarters of the public favored extending controls after the war.

When Harry Truman lost a bitter fight in Congress to do just that, there were consequences. When peace came, Americans eager to spend their stored-up savings ran headlong into a supply shortage: Manufacturers had yet to convert back from wartime production.

In the summer of 1946, without controls, the cost of living jumped. In July, meat prices doubled to 70 cents a pound. In the midterm elections that November, Democrats lost control of Congress for the first time since 1932.

In 1948, with inflation running at 7.7 percent, Truman condemned the “do-nothing” Republicans who placed blame for rising prices on newfound union power. In his re-election campaign that year, he promised to expand the New Deal and ran hard against corporate power. “The Republicans don’t want any price control for one simple reason: the higher prices go up, the bigger the profits for the corporations,” he said that year.

At a campaign stop in Kentucky on October 1948, he lashed out at the National Association of Manufacturers, a business lobbying group that opposed price controls, for engaging in a “conspiracy against the American consumer.” He called Congress into a special summer session to restore price controls, but that effort failed.

Democrats returned to the polls; automobile workers gave Truman 89 percent of their vote, helping him secure re-election in a close contest. One key to his success: doubling down on tough talk against inflation and support for liberal programs to raise living standards for ordinary Americans.

From the presidencies of Truman through Lyndon Johnson, Democrats stuck to the program. Like Truman, who went so far as to order a takeover of the nation’s steel mills when they announced a price hike, John F. Kennedy and Johnson also publicly reprimanded steel executives for price increases.

They all spoke out against efforts by William McChesney Martin, the Fed chairman, to raise interest rates. Martin famously asserted his independence and raised rates anyway; as he saw it, the job of the Federal Reserve was “to take away the punch bowl just as the party is getting good.” Truman called him a “traitor.”

When inflation struck in the 1970s, Richard Nixon understood the expectations created by Roosevelt’s Office of Price Administration. As a World War II-era inspector for the agency, Nixon had been horrified at the thought of bureaucrats checking up on the pricing decisions of private business, and he quit. Yet once in the White House, he didn’t hesitate to slap on price controls in response to the soaring cost of beef and gas.

Milton Friedman, the free-market economist, and other conservatives denounced Nixon’s response as heavy-handed — a message that his successor Gerald Ford absorbed. Instead of price controls, Ford distributed “Whip Inflation Now” buttons and called for budgetary austerity.

As American economic thinking fell under Friedman’s influence, the Roosevelt-Truman tools lost favor. With inflation reaching double digits in 1979, President Jimmy Carter appointed Paul Volcker to the Federal Reserve to use monetary policy to fight inflation. When Ronald Reagan came into office, he endorsed Mr. Volcker’s muscular move to raise interest rates and drive the economy into recession to fight inflation. Subsequent presidents have largely stuck to this approach of controlling inflation.

Amid a pandemic, Mr. Biden has shown a willingness to lean hard on corporate America and embrace New Deal-style tools to lighten inflationary pressures. Through his supply chain task force, he is working to reverse offshoring and outsourcing, expand domestic production and help the ports in Los Angeles stay open round the clock to ease the cargo pileup. His infrastructure bill will allocate billions to construct and operate coastal ports and inland waterways, further easing prices.

Mr. Biden has also warned the big four meat processors against anticompetitive practices that probably contributed to spiking prices, including squeezing out competitors. His administration has pledged to take more aggressive action on illegal price fixing and antitrust, while working to bring more transparency to cattle markets. Higher meat prices are “not just the natural consequences of supply and demand in a free market — they are also the result of corporate decisions to take advantage of their market power in an uncompetitive market, to the detriment of consumers, farmers and ranchers, and our economy,” his economic advisers Brian Deese, Sameera Fazili and Bharat Ramamurti recently wrote.

Through the Federal Trade Commission, Mr. Biden has called for an investigation into the prices set by large oil and gas companies and authorized the release of 50 million barrels of oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve to dampen OPEC’s ability to raise prices. He also met with the chief executives of Walmart, Mattel, Food Lion, Kroger and other companies to discuss their plans to overcome supply-chain problems and keep prices in check for the holidays.

In the coming weeks, Mr. Biden should use his bully pulpit to make clear to Americans that corporations are padding their profits while working families are struggling through the pandemic. Almost two-thirds of publicly traded companies had substantially larger profit margins this year compared to the same period in 2019, before the pandemic. In 2021, close to 100 of them saw their profit margins go up at least 50 percent relative to 2019, The Wall Street Journal reported.

Showing working Americans that he gets it will help Mr. Biden demonstrate that he cares, as the Democratic pollster Joel Benenson told me. “We’re not having an inflation problem,” he said. “We’re having a corporate greed problem. And the president should put the blame where it belongs.”

As Mr. Biden leans on big businesses to temper rising prices, he also needs to push hard for policies that have a much greater impact than fluctuations in gas or meat prices: His stalled Build Back Better legislation would go a long way to ease the burden of major expenses. Mr. Biden promised the bill would lower out-of-pocket costs for child care, care for the elderly, housing, college, health care and prescription drugs — some of the biggest costs that most families face.

Like his Democratic predecessors, Mr. Biden needs to get tough.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

By The Editorial Board, Dec. 24, 2021

The editorial board is a group of opinion journalists whose views are informed by expertise, research, debate and certain longstanding values. It is separate from the newsroom.

Half a century ago, the Supreme Court settled the matter of when a court can stop a newspaper from publishing. In 1971, the Nixon administration attempted to block The Times and The Washington Post from publishing classified Defense Department documents detailing the history of the Vietnam War — the so-called Pentagon Papers. Faced with an asserted threat to the nation’s security, the Supreme Court sided with the newspapers. “Without an informed and free press, there cannot be an enlightened people,” Justice Potter Stewart wrote in a concurring opinion.

That sentiment reflects one of the oldest and most enduring principles in our legal system: The government may not tell the press what it can and cannot publish. This principle long predates the Constitution, but so there would be no mistake, the nation’s founders included a safeguard in the Bill of Rights anyway. “Congress shall make no law,” the First Amendment says, “abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.”

This is why virtually every official attempt to bar speech or news reporting in advance, known as a prior restraint, gets struck down. “Any system of prior restraints of expression comes to this court bearing a heavy presumption against its constitutional validity,” the Supreme Court said in a 1963 case. Such restraints are “the very prototype of the greatest threat to First Amendment values,” Justice Antonin Scalia wrote a generation later.

On Friday, however, a New York trial court judge broke from that precedent when he issued an order blocking The Times from publishing or even reporting further on information it had obtained related to Project Veritas, the conservative sting group that traffics in hidden cameras and fake identities to target liberal politicians and interest groups, as well as traditional news outlets.

The order, a highly unusual and astonishingly broad injunction against a news organization, was issued by State Supreme Court Justice Charles D. Wood, who wrote that the Times’s decision to publish excerpts from memos written by Project Veritas's lawyers “cries out for court intervention to protect the integrity of the judicial process.” This ruling follows a similar directive Justice Wood issued last month in response to a story The Times published that quoted from the memos. The Times plans to appeal this latest ruling.

In requesting the order from Justice Wood, Project Veritas’s lawyers acknowledged that prior restraints on publication are rare but argued that their case fits a narrow exception the law recognizes for documents that may be used in the course of ongoing litigation. This exception recognizes that because parties are forced by the court to disclose materials, courts should have the power to supervise how such forced disclosures are used by the other party. The litigation here is a libel suit Project Veritas filed against The Times in 2020, for its articles on a video the group produced about what it claimed was rampant voter fraud in Minnesota. The video was “probably part of a coordinated disinformation effort,” The Times reported, citing an analysis by researchers at Stanford University and the University of Washington.

The group’s lawyers also argue that the memos are protected by attorney-client privilege and that The Times was under an ethical obligation to return them to Project Veritas, rather than publish them. This is not how journalism works. The Times, like any other news organization, makes ethical judgments daily about whether to disclose secret information from governments, corporations and others in the news. But the First Amendment is meant to leave those ethical decisions to journalists, not to courts. The only potential exception is information so sensitive — say, planned troop movements during a war — that its publication could pose a grave threat to American lives or national security.

Project Veritas’s legal memos are not a matter of national security. In fact, but for its ongoing libel suit, the group would have no claim against The Times at all. The memos at issue have nothing to do with that suit and did not come to The Times through the discovery process. Still, Project Veritas is arguing that their publication must be prohibited because the memos contain confidential information that is relevant to the group’s litigation strategy.

It’s an absurd argument and a deeply threatening one to a free press. Consider the consequences: News organizations could be routinely blocked from reporting information about a person or company simply because the subject of that reporting decided the information might one day be used in litigation. More alarming is the prospect that reporters could be barred even from asking questions of sources, lest someone say something that turns out to be privileged. This isn’t a speculative fear; in his earlier order, Justice Wood barred The Times from reporting about anything covered by Project Veritas’s attorney-client privilege. In Friday’s decision, he ordered The Times to destroy any and all copies of the memos that it had obtained, and barred it from reporting on the substance of those memos. The press is free to report on matters of public concern, he wrote, but memos from attorneys to their clients don’t clear that bar.

This is a breathtaking rationale: Justice Wood has taken it upon himself to decide what The Times can and cannot report on. That’s not how the First Amendment is supposed to work.

Journalism, like democracy, thrives in an environment of transparency and freedom. No court should be able to tell The New York Times or any other news organization — or, for that matter, Project Veritas — how to conduct its reporting. Otherwise, it would provide an incentive for any reporter’s subjects to file frivolous libel suits as a means of controlling news coverage about them. More to the point, it would subvert the values embodied by the First Amendment and hobble the functioning of the free press on which a self-governing republic depends.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Inside the self-reinforcing ecosystem of people who advise, train and defend officers. Many accuse them of slanting science and perpetuating aggressive tactics.

By Jennifer Valentino-DeVries, Mike McIntire, Rebecca R. Ruiz, Julie Tate and Michael H. Keller, Dec. 26, 2021

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/26/us/police-deaths-in-custody-blame.html

When lawyers were preparing to defend against a lawsuit over a death in police custody in Fresno, Calif., they knew whom to call.

Over the past two decades, Dr. Gary Vilke has established himself as a leading expert witness by repeatedly asserting that police techniques such as facedown restraints, stun gun shocks and some neck holds did not kill people.

Officers in Fresno had handcuffed 41-year-old Joseph Perez and, holding him facedown on the ground, put a spinal board from an ambulance on his back as he cried out for help. One officer sat on the board as they strapped him to it. The county medical examiner ruled his death, in May 2017, a homicide by asphyxiation.

Dr. Vilke, who was hired by the ambulance provider, charged $500 an hour and provided a different determination. He wrote in a report filed with the court this past July that Mr. Perez had died from methamphetamine use, heart disease and the exertion of his struggle against the restraints.

Dr. Vilke, an emergency medicine doctor in San Diego, is an integral part of a small but influential cadre of scientists, lawyers, physicians and other police experts whose research and testimony is almost always used to absolve officers of blame for deaths, according to a review of hundreds of research papers and more than 25,000 pages of court documents, as well as interviews with nearly three dozen people with knowledge of the deaths or the research.

Their views infuriate many prosecutors, plaintiff lawyers, medical experts and relatives of the dead, who accuse them of slanting science, ignoring inconvenient facts and dangerously emboldening police officers to act aggressively. One of the researchers has suggested that police officers involved in the deaths are often unfairly blamed — like parents of babies who die of sudden infant death syndrome.

The experts also intersect with law-enforcement-friendly companies that train police officers, write police policies and lend authority to studies rebutting concerns about police use of force.

Together they form what often amounts to a cottage industry of exoneration. The dozen or so individuals and companies have collected millions of dollars over the past decade, much of it in fees that are largely underwritten by taxpayers, who cover the costs of police training and policies and the legal bills of accused officers.

Many of the experts also have ties to Axon, maker of the Taser: A lawyer for the company, for example, was an early sponsor of the Institute for the Prevention of In-Custody Deaths, a commercial undertaking that is among the police-friendly entities, and some of the experts have worked as consultants for Axon; another has served on Axon’s corporate board.

The New York Times identified more than 100 instances of in-custody deaths or life-threatening injuries from the past 15 years in which experts in the network were hired to defend the police. The cases were nearly all civil lawsuits, as the officers involved were rarely charged with crimes. About two-thirds of the cases were settled out of court; of the 28 decided by judges or juries, 16 had outcomes favoring the police. (A handful of cases are pending.)

Beyond the courtroom, the individuals and businesses have offered instruction to thousands of police officers and medical examiners, whose cause-of-death rulings often help determine legal culpability. Lexipol, a Texas-based business whose webinars and publications have included experts from the network, boasts that it helped write policy manuals for 6,300 police departments, sometimes suggesting standards for officers’ conduct that reduce legal liability. A company spokeswoman said it did not rely on the researchers in making its policies.

The self-reinforcing ecosystem underscores the difficulty of obtaining an impartial accounting of deaths in police custody, particularly in cases involving a struggle, where the cause of death is not immediately clear. The Times reported earlier this year that outside criminal investigations of such cases can be plagued with shortcuts and biases that favor the police, and that medical examiners sometimes tie the deaths to a biological trait that would rarely be deemed fatal in other circumstances.

Some researchers and doctors in this ecosystem who responded to questions from The Times said they did not assist law enforcement but provided unbiased results of scientific research and opinions based on the facts of each case. Several pointed to research demonstrating that police struggles overall have an exceedingly low risk of death. They also highlighted health issues that could cause deaths in such circumstances, including drug use, obesity, psychological disturbances and genetic mutations that may predispose people to heart problems.

Some also criticized research and medical opinions that found that police techniques might cause or contribute to deaths, suggesting these were flawed. They also pointed out that other academic papers have been written by people who testify against law enforcement in such cases.

“Sensationalism, without offering scientifically demonstrated better control techniques, adds no benefit, and merely exacerbates the existing tensions between law enforcement and the society at large,” said Mark Kroll, a biomedical engineer who has backed the idea of an “arrest related death syndrome” as an explanation of the deaths.

Others in the network, including Dr. Vilke, said it was wrong to characterize their work as favoring the police, and suggested The Times’s analysis misrepresented it. “I would disagree,” Dr. Vilke said when The Times shared its findings with him. Another of the experts, Dr. Steven Karch, sent papers suggesting Black males and people exerting themselves were generally more likely to have sudden cardiac death.

Lawyers for Derek Chauvin, the former Minneapolis police officer who was ultimately convicted in last year’s murder of George Floyd, also drew upon the same network of researchers and experts. In particular, they turned to the defense of prone restraint, a technique in which officers subdue subjects facedown, as happened to Mr. Floyd. The work of Dr. Kroll, who has a Ph.D in electrical engineering but no medical degree, was cited by the Chauvin defense as proof that putting body weight on someone facedown does not cause asphyxia.

The experts have been called on to defend a broad range of other police techniques, including Taser shocks and neck holds. Medical examiners and investigators have also relied on the research:

· Omaha police officers used a Taser 12 times when detaining Zachary Bear Heels in 2017 and punched him repeatedly in the head and neck. Dr. Kroll, who sits on Axon’s corporate board, testified in the criminal trial that the stun gun could not have contributed to the death of Mr. Bear Heels, a 28-year-old with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. He also wrote a report in the civil case that is under seal.

· Officers in Phoenix held Miguel Ruiz in a neck hold and shocked him multiple times with a stun gun in 2013. In a civil case, Dr. Vilke attested to the safety of neck holds that cut off blood flow to the head by compressing arteries, and another researcher, Dr. Charles Wetli, discussed excited delirium, a condition that some doctors say can suddenly kill drug users or the mentally ill.

· Sheriff’s deputies in Kern County, Calif., handcuffed David Silva in 2013, bloodied him with batons, tied his hands and feet together behind his back, and pushed him facedown into the ground. Two physicians in the expert network, Dr. Karch and Dr. Theodore Chan, agreed with the coroner’s finding that Mr. Silva did not asphyxiate; Dr. Chan cited studies he had done on the subject.

Dr. Chan, who works in San Diego with Dr. Vilke, is also serving as an expert witness in the lawsuit over the death of Mr. Perez in Fresno. Citing his own research, he stated that there was “no evidence” that such weight on a person’s back could contribute to asphyxiation.

According to court documents, Mr. Perez had recently taken methamphetamines when police saw him behaving erratically. They handcuffed and tried to calm him, at one point putting a towel under him to keep him from injuring his face.

After an ambulance arrived, they placed a backboard on top of him and an officer sat on it. In a deposition, the officer said he had been trained that doing so posed no danger of asphyxia. A captain from the department said in the case that the training had relied on an article by Dr. Kroll.

“The problem is that when officers get sued in these cases,” said Neil Gehlawat, the lawyer for Mr. Perez’s family, the cadre of researchers insist that “‘no one can die this way,’ and then officers start to believe it.”

Mr. Perez’s sister, Michelle Perez, said that watching the video of his death was “terrifying” and that she didn’t understand why officers would push him facedown and sit on him.

“I just kept thinking, ‘Get off of him!’” she said. “There could have been some kind of different tactic.”

Shaping the Science

The physicians, scientists and researchers who come to the defense of law enforcement officers often cite experiments conducted on volunteers. They shock them with Tasers, douse them with pepper spray or restrain them facedown on the ground.

Their published findings are usually the same: that there is no evidence that the actions have enough of an effect to cause death.

A Times analysis of more than 230 scientific papers in the National Library of Medicine database published since the 1980s showed those conclusions to be significantly different from those published by others, including studies about restraints, body position and excited delirium.

Nearly three-quarters of the studies that included at least one author in the network supported the idea that restraint techniques were safe or that the deaths of people who had been restrained were caused by health problems. Only about a quarter of the studies that did not involve anyone from the network backed that conclusion. More commonly, the other studies said some restraint techniques increased the risk of death, if only by a small amount.

The few studies by the group that found problems with police techniques focused on deaths in which Tasers ignited gas fumes or caused people to fall and hit their heads.

Dr. Vilke’s first report on police restraint was funded by a $33,900 grant from San Diego County during a lawsuit over the 1994 death of Daniel Price. A woman reported seeing odd behavior from Mr. Price, 37, who had taken methamphetamines; officers restrained him facedown, his hands and feet tied together.

As part of their research, Dr. Vilke and others hogtied healthy volunteers. They observed that measurements of their lung functions decreased by up to 23 percent, which they concluded was not clinically significant because similar levels of diminished lung capacity could still be considered normal. The judge in the Price case cited the research when he dismissed the lawsuit.

TRIAL TESTIMONY DECLARATION OF DR. TOM NEUMAN

As concerns, a knee in Price’s back, whether after the hogtie or before the hogtie, if having a knee in your back caused asphyxia after struggle, along with being overweight, and being on your stomach, I think we can safely say that there would not be a single professional wrestler alive today.

The study and others have been challenged by some scholars and physicians because they are based on controlled conditions that are unlike real life, said Justin Feldman, a social epidemiologist at Harvard University who studies patterns of deaths in law enforcement custody.

“There’s a fundamental problem in terms of study design,” he said. “They’re not using people with more severe mental and physical disabilities. They’re not doing it with people who have taken drugs. When they’re testing Tasers, they aren’t using them as many times as you might see in some deaths.”

When their studies appeared in peer-reviewed publications, the network of experts acknowledged that their work had limitations. But when discussing the research in court, or during trainings and elsewhere, some of them used more expansive language, did not mention conflicting work, or said they had fully refuted scholars who disagreed.

In the Fresno lawsuit and others, for example, Dr. Chan repeatedly wrote that Dr. Donald Reay, a former medical examiner in King County, Wash., had concluded that hogtying “does not produce any serious or life-threatening respiratory effects” — omitting the crucial phrase “in normal individuals.” Other physicians in the network consistently left off that phrase when repeating the quote, although Dr. Reay maintained that such restraints could be fatal in some instances.

Dr. Chan did not respond to a question about the quotation.

Papers by researchers outside the network were more frequently balanced — finding, for example, that some restraint positions are generally safe while others can cause statistically significant changes in breathing. Another recent paper used new computer imaging technology to measure lung function and found that it was affected during restraint.

In their own writings and when asked about these papers, some scientists in the network dismissed them. They said papers that found “statistically significant” effects were inadequate because the changes were not “clinically significant” enough to be considered health problems in the participants. (Some other scientists said choosing test subjects who would be more likely to face such distress would generally not be ethically permitted in experiments.) They said some experiments with Tasers on animals could not be used to draw conclusions about humans. And several suggested that some of the other papers should be scrutinized because they were written by doctors who testified against police.

Dr. Kroll said in a 2019 webinar that “the science has completely debunked” the claim that pushing someone facedown could contribute to asphyxiation. In the session, conducted by Lexipol and titled “Arrest Related Deaths: Managing Your Medical Examiner,” he suggested that such deaths were outside the control of officers.

“Decades ago we used to prosecute mothers for crib deaths and sudden infant death syndrome, and then we figured out it really wasn’t their fault,” he said at one point in the training session, adding later: “Hopefully in the future we’ll have something like sudden infant death syndrome, just ‘arrest related death syndrome’ so we don’t have to automatically blame the police officer.”

A spokeswoman for Lexipol, which was co-founded by a lawyer who had previously hired Dr. Chan to defend police officers, said an upcoming webinar would discuss recent court rulings that found extended prone restraint to be excessive force in some circumstances.

“We are not in the business of determining such science-based decisions” about whether prone restraint is dangerous, the spokeswoman, Shannon Pieper, said in an email.

Some of the scientists are fierce defenders of their approach, vigorously challenging anyone who suggests an alternative finding. They submit letters to the editors of medical journals that publish the opposing research, discredit it in textbooks they write and routinely dismiss it as “junk science” in public forums.

One cardiologist, Dr. Peyman Azadani, said in an interview that he was intimidated by the pushback. In a 2011 academic paper, he reviewed studies by authors associated with Taser and found they were far more likely than others to conclude that the devices were safe.

Dr. Azadani said two people who identified themselves as being affiliated with Taser had approached him about the research during a medical conference.

“They knew everything about my background, and they told me I was destroying my future,” he recalled.

Having recently immigrated from Iran at the time, Dr. Azadani was concerned about making waves, he said, so he removed his name from subsequent papers and then changed research subjects.

In a statement, Axon said it had no information about the incident but did not condone such behavior. The company said it promoted research into its devices out of a concern for safety, and Dr. Kroll, who makes more than $300,000 a year as a member of Axon’s corporate board, pointed to a more recent study that found no correlation between Taser funding and safety determination.

A Network Forms

Dr. Wetli, a former Miami medical examiner who died last year, was among the first to publish research that launched what has become an industry of sorts defending police officers. He wrote in the 1980s about men who had taken cocaine and died, many while being subdued by the police. He attributed the deaths to a condition he called excited delirium, when someone becomes aggressive from a mental illness or psychoactive drugs.

Later, in 1994, two former law enforcement officers, Michael A. Brave and John G. Peters Jr., described in a paper what they called custody death syndrome. The condition, they wrote, had “no apparent detectable anatomical cause” but could be associated with excited delirium or other vague diagnoses.

In describing the death of a hypothetical suspect, they focused on potential liability: “You immediately cringe at the thought of the critical scrutiny you will soon be facing by the media, by council officials and by special interest groups,” they wrote.

The two men later became affiliated with both the Institute for the Prevention of In-Custody Deaths and Americans for Effective Law Enforcement, another group that provides legal resources for officers. Mr. Brave also became a lawyer for Taser.

In the early 2000s, as Tasers were adopted more widely, studies about them proliferated. A group of researchers led by Dr. Jeffrey Ho in Minneapolis pioneered the work. In their initial study, funded in part by Taser, they shocked volunteers for five seconds and concluded that measurements of heart health did not change.

For years, Dr. Ho has worked in emergency medicine at Hennepin Healthcare, as a part-time sheriff’s deputy and, until 2019, as the medical director for Axon.

Taser was also present at the creation of the Institute for the Prevention of In-Custody Deaths, which was founded in 2005 by Mr. Peters.

In an interview, Mr. Peters said he started the business because so many deaths were being blamed on Tasers, which he characterized as one of many misguided criticisms of police conduct. The institute conducts research and training that often rebuts the criticism and is one of several commercial forums that draw like-minded researchers about law enforcement behavior.

“When we first started teaching this stuff back in the ’90s, it was all pepper spray deaths,” he said. “Well, then they did the science and showed that of all the people who died, only two may have been associated with pepper spray. So that issue went away. Then positional asphyxia popped up. So we did a little bit of work in that area and then that quieted down.”

Taser provided some early funding to the institute in exchange for training programs, Mr. Peters said, and one of its initial sponsors was Mr. Brave, who joined Taser’s legal department around the same time.

“We put him on the board the first year so we would have a connection to information at Taser,” Mr. Peters said.

The institute had also worked closely with Deborah C. Mash, a neuroscientist who has written papers about excited delirium. When Dr. Mash was affiliated with the University of Miami, Mr. Peters and Taser representatives recommended that medical examiners send brain tissue samples from people who had died in police custody to her lab for testing. The Times found a handful of instances in which medical examiners relied on these test results to determine that someone had died of excited delirium as well as one case in which the results were used to rule it out.

Dr. Mash left the university in 2018. In an email to The Times, she said she tells officers that excited delirium is a medical emergency and that the proper response is to immediately request emergency medical help.

Another private company that lends expert support for the police, the Force Science Institute, has promoted research and commentary by Dr. Kroll, including a paper he wrote with Mr. Brave and Dr. Karch that tested law enforcement officers pressing their knees into a prone person’s back. They said their results did not support the theory that this could cause asphyxia.

The business of supporting law enforcement can be lucrative. Not all of the researchers testify frequently in court, but when they do, experts associated with the network typically earn $500 to $1,000 an hour for testimony and depositions. Lexipol charges thousands of dollars to review and write policies for police departments. The Institute for the Prevention of In-Custody Deaths also charges for its training programs and promotes its business partners.

At the institute’s annual conference in Las Vegas last month, law enforcement officers, lawyers and physicians attended presentations, some by experts in the network, on such topics as ways to subdue or restrain a suspect, and how to manage publicity when someone is injured or dies in custody. The price of admission: $695.

One-Sided Track Record

The Times found that, with rare exceptions, when members of this network weigh in on a case in court, they side with the police.

In court documents and testimony, some of them have acknowledged their one-sided track record.

“That’s like trying to retain Columbus to testify that the Earth is flat,” Dr. Tom Neuman, a retired emergency medicine physician in San Diego, said in 2018 when asked if relatives of people who had died in police custody would ever hire him as an expert.

In a deposition this past summer, Dr. Vilke said it had been 20 years since he had last testified that an officer was likely to have contributed to a death. In an email to The Times, he said that he had “no independent recall” about specific earlier work, and “would disagree” that his work over the past 20 years almost always found that law enforcement was not to blame.

Mr. Peters, who founded the training institute, is an exception. He has testified regularly on behalf of people harmed in police encounters, or their families, but his testimony has been limited to whether police procedures were followed. After Mr. Floyd was killed in Minneapolis, Mr. Peters released a video statement saying that putting a knee on a someone’s neck should not be permitted under any use-of-force policy.

Making determinations on death-in-custody cases is a complex and inexact process. The people being detained in the instances reviewed by The Times were often on drugs or in psychological distress, and some had severe medical conditions.

But in death after death, The Times found, actions by law enforcement officers fell well outside the controlled conditions in the research the experts cited to exonerate them. Occasionally, the experts used identical language in different cases to rebut allegations and suggest alternative explanations for the deaths. They also emphasized common ailments like heart disease, or leaned heavily on the poorly understood notion of excited delirium.

DR. VILKE’S REPORT IN THE PEREZ CASE

It should be noted that in the video Mr. Perez could be heard at least once saying, “I can’t breathe” right after the backboard was placed on his back before Detective Calvert sat on the board. At face value, one might think this evidence that Mr. Perez could not breathe or ventilate. However, when evaluating the video, Mr. Perez was clearly moving air in and out of his lungs at this time, talking loudly, and had no clinical evidence of ventilatory restriction at the time he was saying this. What was likely happening is that Mr. Perez was having a cardiac event not a pulmonary event.

DR. VILKE’S REPORT IN THE BARRERA CASE THE FOLLOWING MONTH

(DIFFERENCES HIGHLIGHTED)

It should be noted that in the video that after being handcuffed on laying on the ground, Mr. Barrera could be heard stating, “I can’t breathe” shortly after he asked for some water. At face value, one might think this evidence that Mr. Barrera could not breathe or ventilate. However, when evaluating the video, Mr. Barrera was clearly moving air in and out of his lungs very well, talking loudly, and had no clinical evidence of ventilatory restriction at the time he was saying this. What was likely happening is that Mr. Barrera was having a cardiac event not a pulmonary event.

In 2010, officers in Palm Desert, Calif., responding to a 911 call found 48-year-old Robert Appel delusional. Multiple officers pinned him facedown with their knees. When they turned him over after what the officers described as a short time, he was dead. Dr. Vilke blamed cardiac arrest caused by undiagnosed kidney failure.

Mathew Ajibade hit his girlfriend in January 2015 while experiencing what his family described as a manic bipolar episode. Deputies in Savannah, Ga., beat him, handcuffed him, put him in a restraint chair with a spit mask over his face and shocked him four times in the groin with a Taser.

Dr. Mash and Dr. Wetli both reported that the actions had not led to Mr. Ajibade’s death. Dr. Mash blamed natural causes associated with his bipolar disorder and said he exhibited signs of excited delirium, while Dr. Wetli said it was related to sickle cell trait, a typically benign condition in which a person carries one of the two genes that together cause sickle cell disease.

Assessing the effectiveness of the opinions exonerating the police is difficult because most cases settle or are decided without explanation.

But several cases reviewed by The Times suggest that the research has had far-reaching effects — influencing investigator decisions in death inquests and giving officers assurance that their methods are safe. Some of the experts’ legal statements and educational materials they have prepared for police called safety warnings by Taser and other law enforcement groups outdated or needlessly conservative.

In a deposition in April, the sheriff in Riverside County, Calif., cited studies backed by the law-enforcement-leaning experts to explain why his deputies held people facedown after handcuffing them. The sheriff, Chad Bianco, described the position as “the absolute safest place for any subject.”

Two years ago, deputies working for Sheriff Bianco found Kevin Niedzialek, 34, bleeding from a head wound and behaving strangely after taking methamphetamines. They shocked him twice with a Taser, and held him facedown.

When they rolled him onto his back, Mr. Niedzialek was unresponsive. He died the next day.

Produced by Eden Weingart

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

The police said they expected to release more details on Monday about the shooting, which happened after officers responded to a call about an assault with a deadly weapon at a clothing store.

By Christine Chung and Giulia Heyward, Dec. 26, 2021

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/26/us/14-year-old-girl-shot-valentina-orellana-peralta.html

Flowers were left in memory of Valentina Orellana-Peralta, 14, who was killed after the police opened fire on a man reported to be assaulting a woman. Credit...Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times, via Getty Images

The Los Angeles Police Department is expected on Monday to release more details, including audio from 911 calls and body camera video footage, about an encounter between officers and a man reported to be assaulting a woman that resulted in the fatal shooting of a 14-year-old girl in a North Hollywood clothing store on Thursday.

Officers responded to multiple radio calls about an assault with a deadly weapon and a potential shooting at a Burlington store on Victory Boulevard, the police said. When officers arrived, they said, they found a man assaulting a woman and fired at him. They identified him as Daniel Elena Lopez.

The teenager, Valentina Orellana-Peralta, was in a dressing room with her mother directly behind him, and the officers did not see her. Police said a bullet, likely fired by an officer, penetrated the dressing room’s wall.

Both the man and the girl died from gunshot wounds to the chest, according to the Los Angeles County Coroner’s Office. They were both pronounced dead at the scene.

Upon surveying the scene after Mr. Elena Lopez’s death, officers then discovered Ms. Orellana-Peralta’s body, the police said.

The unidentified woman who was reported to have been assaulted was taken to a hospital for injuries to her head and arms, Dominic H. Choi, assistant chief of the Los Angeles Police Department, said at a news conference on Thursday. Chief Choi said officers found a heavy metal lock near the man but no gun.