URGENT ACTION NEEDED!

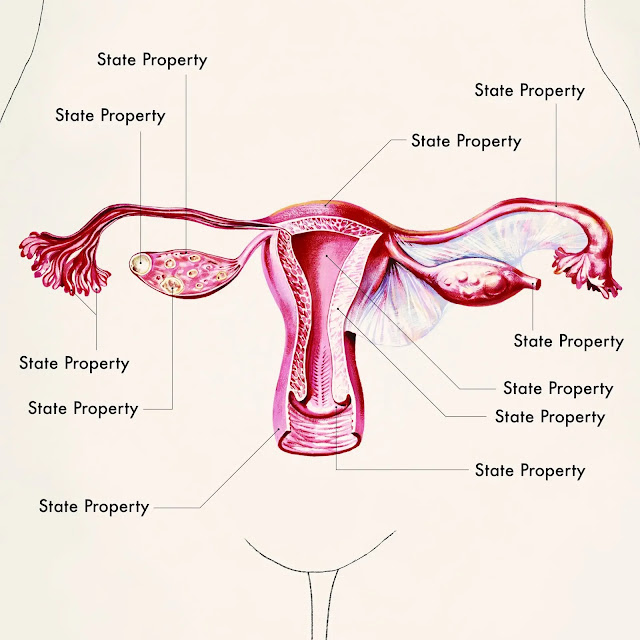

We demand that ALL "illegal abortion" charges against Madison County, Nebraska women be dropped

In Madison County, Nebraska, two women- one the mother of a pregnant teenager who was a minor at the time of her pregnancy and is being charged as an adult- are facing prosecution for self managing an abortion. In an outrageous violation of civil liberties, Facebook assisted the police and county attorney in this case by turning over communication between the daughter and her mother regarding obtaining abortion pills which is not illegal in Nebraska. The prosecutor has used this information to charge the daughter, her mother, and a male friend who assisted them after the fact with illegal abortion along with additional trumped up charges of "concealing a body."

We demand that ALL charges be dropped against all three of them and we ask that you call the office of Madison County Attorney Joseph Smith at 402-454-3311 Ext. 206 with the following:

"I am calling to demand that all charges against Jessica Burgess, her daughter, and their friend be dropped. In your own words- no charges like this have ever been brought before. That is because criminalizing abortion is unjust and unconstitutional. We will not stand for any charges being brought against any pregnant person for the outcome of their pregnancy OR anyone who assists that pregnant person. Drop all charges NOW."

You can also email County Attorney Smith here.

If you pledged to #AidAndAbetAbortion- NOW is the time to stand up for these women in Nebraska as this could be any of us in the future.

About NWL

National Women's Liberation (NWL) is a multiracial feminist group for women who want to fight male supremacy and gain more freedom for women. Our priorities are abortion and birth control, overthrowing the double day, and feminist consciousness-raising.

NWL meetings are for women and tranpeople who do not benefit from male supremacy because we believe we should lead the fight for our liberation. In addition, women of color meet separately from white women in Women of Color Caucus (WOCC) meetings to examine their experiences with white supremacy and how it intersects with male supremacy to oppress women of color.

Learn more at womensliberation.org.

Questions? Email nwl@womensliberation.org for more info.

No to red-baiting in the reproductive justice movement

National Radical Women statement

By Nga Bui, NYC

At a time when a united mass movement to defend reproductive justice is needed more than ever, NYC for Abortion Rights and nearly two dozen organizations have chosen to launch an anti-communist attack against one of the most visible activist groups, Rise Up 4 Abortion Rights. Radical Women, a veteran socialist feminist organization with decades of experience in the movement for reproductive justice, denounces this dangerous game of divide and conquer.

The “Statement Against RiseUp4AbortionRights” – signed by NYC for Abortion Rights, United Against Racism & Fascism NYC, Brooklyn People’s March, Shout Your Abortion, The Jane Fund, Chicago Abortion Fund, Chicago DSA Socialist Feminist Working Group and others – deplores Rise Up’s connections to the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP). It labels this well-known fixture on the Left as a personality cult. It accuses both Rise Up and RCP of using pyramid schemes to raise money and exploitative methods to recruit. These unsubstantiated claims are bolstered by other “crimes”: wearing white pants stained with fake blood, holding die-ins, using coat-hanger imagery, and describing forced pregnancy as “female enslavement.” The Statement calls on “repro groups to now unite in discrediting Rise Up publicly” and demand that “the group step back from pro-abortion spaces.” This divisive attack is like a dog-whistle to corporate media, which is crawling all over the issue in coverage from Daily Beast and The Intercept.

Imperfect as Rise Up may be, the reality is the group has been out front nationally in defense of abortion – though not the only group as they have claimed. It has consistently organized protests and used audacious tactics such as unfurling huge banners at sports events to draw media attention to the issue. It has broadened its messaging after being criticized that its single-issue focus on women having abortions was transphobic and limiting. Its green wave imagery is omnipresent and its anti-capitalist message is spot-on. Its boldness has resonated with youth.

Truth be told, it has been largely the Left, including Radical Women, that organized rallies, speak outs, marches, and protests throughout last year to draw attention to the impending Supreme Court debacle. Meanwhile, moderate feminist organizations pushed online fundraising and waited for the Democratic Party to ride to the rescue.

One has to think that some of the venom expressed in the Statement is from groups that did much less than Rise Up and may begrudge its appeal to young people. Others may be driven to undermine the influence of the Left in the movement overall. How condescending it is for them to demand that Rise Up disappear rather than trust young supporters to reach their own conclusions about whether Rise Up’s strategies work in the long run.

Radical Women initiated the National Mobilization for Reproductive Justice a year ago in order to build the kind of coalition effort we think is urgently needed to preserve abortion and achieve full reproductive justice. The Mobilization has attracted feminist groups, grassroots organizations, unions, radicals, and individuals coming together in common cause. Though Rise Up in many instances put itself in competition with actions announced by the Mobilization, we managed to work cooperatively with it in various cities, including in NYC. Rather than demanding political conformity, we believe in respectfully debating differences. With the right wing intensifying its attacks on the most vulnerable, a united front of working-class organizations is essential to pushing them back.

Red-baiting, smearing people or groups for their radical associations, is not acceptable in the movement. It needs to be stopped before it further hurts the very women, people of color, non-binary, trans and poor folks looking to find a channel for their rage as their rights are stripped away. There’s no denying that those of us fighting for abortion rights and reproductive justice will have differences of opinions. It is essential we learn to work together with mutual respect instead of excluding, silencing and witch-hunting one another. Organizations and independent activists can unite around issues while maintaining our differences. The future of reproductive justice and all social movements depends on it.

CUBA URGENTLY NEEDS OUR HELP TODAY!

MATANZAS IS NOT ALONE!

https://www.hatueyproject.org

The unprecedented massive fire at the Supertanker Base in Matanzas province has not abated. Dozens of people have suffered burns, 16 firefighters are still missing, and thousands are evacuated. Heroic efforts by firefighters and civil defense are 24/7.

Supplies are urgently needed to save the lives of the burn and other victims affected by the fire. The Hatuey Project is working to provide some of the most critical supplies for burn and other patients.

Please make a monetary donation so we can buy medical items in bulk and ship immediately to Matanzas.

Cuba has been through so much during the time of pandemic. Despite a heroic and successful campaign to vaccinate virtually all of Cuba from COVID, this summer has been particularly taxing for all of Cuba. Now the fire has added to the hardship.

Please click here to make a donation to The Hatuey Project for Matanzas Relief. Every donation to Hatuey is tax-deductible through our fiscal sponsor, The Alliance for Global Justice.

On behalf of The Hatuey Project, we thank you.

Nadia Marsh, MD, Assoc. Prof. of Clinical Medicine

Simon Ma, MD, MPH, Family Medicine

Rachel Viqueira, MHS, Epidemiologist

Brian Becker, Executive Director, ANSWER Coalition

Gloria La Riva, coordinator, Hatuey Project

ABOUT THE HATUEY PROJECT

We are health providers and social justice activists concerned about the harmful effects of the U.S. economic blockade of Cuba. We have inaugurated this medical aid project to extend solidarity to the Cuban people, with the procurement of vital medicines and medical equipment.

Cuba has already shown that its remarkable health care and scientific/biotech systems are fully capable of serving the 11+ million people on the island, providing excellent quality, universal and free care to everyone. But more than 240 measures by the Trump administration that turned the screws even further on Cuba’s people — in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic — have created a truly difficult situation for the people. We have already taken part in direct delivery of vital medicines over the last year, and we aim to do much more.

We invite you to join in our project in any way you can: With your monetary contribution, as well as helping procure major donations from pharmaceuticals and other medical providers. We are fully volunteer; all of the donations we receive will go strictly to acquire medical aid. Shipping costs will be held to the utmost minimum. The Hatuey Project is fiscally sponsored by the Alliance For Global Justice, so all donations are tax-deductible. Join our effort today!

https://www.hatueyproject.org

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Waging Peace Exhibit In San Francisco

Veterans Gallery, San Francisco

June 29 – August 14, 2022

1:00-6:00 P.M.

Veterans Building

401 Van Ness Ave., Suite. 102

San Francisco, CA

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

The Rock, Bernal Hill, San Francisco

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Olivia Rodrigo - F*** You

(feat. Lily Allen) (Glastonbury 2022)

Lyrics:

https://genius.com/Olivia-rodrigo-fuck-you-lyrics

Fuck You

With Olivia Rodrigo and Lily Allen

[Verse 1: Lily Allen]

Look inside, look inside your tiny mind

Then look a bit harder

'Cause we're so uninspired, so sick and tired

Of all the hatred you harbour

So you say it's not okay to be gay

Well, I think you're just evil

You're just some racist who can't tie my laces

Your point of view is medieval

[Chorus: Lily Allen]

Fuck you, fuck you very, very much

'Cause we hate what you do

And we hate your whole crew

So please, don't stay in touch

Fuck you, fuck you very, very much

'Cause your words don't translate

And it's getting quite late

So please, don't stay in touch

[Verse 2: Olivia Rodrigo, Lily Allen & Olivia Rodrigo]

Do you get, do you get a little kick out of being small minded?

You want to be like your father, it's approval you're after

Well, that's not how you find it

Do you, do you really enjoy living a life that's so hateful?

'Cause there's a hole where your soul should be

You're losing control of it

And it's really distasteful

[Chorus: Olivia Rodrigo, Lily Allen & Olivia Rodrigo]

Fuck you, fuck you very, very much

'Cause we hate what you do

And we hate your whole crew

So please, don't stay in touch

Fuck you, fuck you very, very much

'Cause your words don't translate

And it's getting quite late

So please, don't stay in touch

[Bridge: Crowd]

Fuck you, fuck you, fuck you

Fuck you, fuck you, fuck you

Fuck you

[Verse 3: Lily Allen]

You say you think we need to go to war

Well, you're already in one

'Cause it's people like you that need to get slew

No one wants your opinion

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Doctors for Assange Statement

Doctors to UK: Assange Extradition

‘Medically & Ethically’ Wrong

https://consortiumnews.com/2022/06/12/doctors-to-uk-assange-extradition-medically-ethically-wrong/

Ahead of the U.K. Home Secretary’s decision on whether to extradite Julian Assange to the United States, a group of more than 300 doctors representing 35 countries have told Priti Patel that approving his extradition would be “medically and ethically unacceptable”.

In an open letter sent to the Home Secretary on Friday June 10, and copied to British Prime Minster Boris Johnson, the Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice Robert Buckland, the Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and the Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong, the doctors draw attention to the fact that Assange suffered a “mini stroke” in October 2021. They note:

“Predictably, Mr Assange’s health has since continued to deteriorate in your custody. In October 2021 Mr. Assange suffered a ‘mini-stroke’… This dramatic deterioration of Mr Assange’s health has not yet been considered in his extradition proceedings. The US assurances accepted by the High Court, therefore, which would form the basis of any extradition approval, are founded upon outdated medical information, rendering them obsolete.”

The doctors charge that any extradition under these circumstances would constitute negligence. They write:

“Under conditions in which the UK legal system has failed to take Mr Assange’s current health status into account, no valid decision regarding his extradition may be made, by yourself or anyone else. Should he come to harm in the US under these circumstances it is you, Home Secretary, who will be left holding the responsibility for that negligent outcome.”

In their letter the group reminds the Home Secretary that they first wrote to her on Friday 22 November 2019, expressing their serious concerns about Julian Assange’s deteriorating health.

Those concerns were subsequently borne out by the testimony of expert witnesses in court during Assange’s extradition proceedings, which led to the denial of his extradition by the original judge on health grounds. That decision was later overturned by a higher court, which referred the decision to Priti Patel in light of US assurances that Julian Assange would not be treated inhumanely.

The doctors write:

“The subsequent ‘assurances’ of the United States government, that Mr Assange would not be treated inhumanly, are worthless given their record of pursuit, persecution and plotted murder of Mr Assange in retaliation for his public interest journalism.”

They conclude:

“Home Secretary, in making your decision as to extradition, do not make yourself, your government, and your country complicit in the slow-motion execution of this award-winning journalist, arguably the foremost publisher of our time. Do not extradite Julian Assange; free him.”

Julian Assange remains in High Security Belmarsh Prison awaiting Priti Patel’s decision, which is due any day.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Sign the petition:

https://dontextraditeassange.com/petition/

If extradited to the United States, Julian Assange, father of two young British children, would face a sentence of 175 years in prison merely for receiving and publishing truthful information that revealed US war crimes.

UK District Judge Vanessa Baraitser has ruled that "it would be oppressive to extradite him to the United States of America".

Amnesty International states, “Were Julian Assange to be extradited or subjected to any other transfer to the USA, Britain would be in breach of its obligations under international law.”

Human Rights Watch says, “The only thing standing between an Assange prosecution and a major threat to global media freedom is Britain. It is urgent that it defend the principles at risk.”

The NUJ has stated that the “US charges against Assange pose a huge threat, one that could criminalise the critical work of investigative journalists & their ability to protect their sources”.

Julian will not survive extradition to the United States.

The UK is required under its international obligations to stop the extradition. Article 4 of the US-UK extradition treaty says: "Extradition shall not be granted if the offense for which extradition is requested is a political offense."

The decision to either Free Assange or send him to his death is now squarely in the political domain. The UK must not send Julian to the country that conspired to murder him in London.

The United Kingdom can stop the extradition at any time. It must comply with Article 4 of the US-UK Extradition Treaty and Free Julian Assange.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Dear friends,

Recently I’ve started working with the Coalition to Free Ruchell Magee. On March 17, Ruchell turned 83. He’s been imprisoned for 59 years, and now walks with a walker. He is no threat to society if released. Ruchell was in the Marin County Courthouse on August 7, 1970, the morning Jonathan Jackson took it over in an effort to free his older brother, the internationally known revolutionary prison writer, George Jackson. Ruchell joined Jonathan and was the only survivor of the shooting that ensued. He has been locked up ever since and denied parole 13 times. On March 19, the Coalition to Free Ruchell Magee held a webinar for Ruchell for his 83rd birthday, which was a terrific event full of information and plans for building the campaign to Free Ruchell. (For information about his case, please visit: www.freeruchellmagee.org.)

Below are two ways to stream this historic webinar, plus

• a petition you can sign

• a portal to send a letter to Governor Newsom

• a Donate button to support his campaign

• a link to our campaign website.

Please take a moment and help.

Note: We will soon have t-shirts to sell to raise money for legal expenses.

Here is the YouTube link to view the March 19 Webinar:

https://youtu.be/4u5XJzhv9Hc

Here is the Facebook link:

https://fb.watch/bTMr6PTuHS/

Sign the petition to Free Ruchell:

https://actionnetwork.org/petitions/governor-newsom-free-82-year-old-prisoner-ruchell-magee-unjustly-incarcerated-for-58-years

Write to Governor Newsom’s office:

https://actionnetwork.org/letters/free-82-year-old-prisoner-ruchell-magee-unjustly-incarcerated-for-58-years?source=direct_link

Donate:

https://www.paypal.com/donate/?hosted_button_id=GVZG9CZ375PVG

Ruchell’s Website:

www.freeruchellmagee.org

Thanks,

Charlie Hinton

ch.lifewish@gmail.com

No one ever hurt their eyes by looking on the bright side

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Tell Congress to Help #FreeDanielHale

U.S. Air Force veteran, Daniel Everette Hale has recently completed his first year of a 45-month prison sentence for exposing the realities of U.S drone warfare. Daniel Hale is not a spy, a threat to society, or a bad faith actor. His revelations were not a threat to national security. If they were, the prosecution would be able to identify the harm caused directly from the information Hale made public. Our members of Congress can urge President Biden to commute Daniel's sentence! Either way, Daniel deserves to be free.

https://oneclickpolitics.global.ssl.fastly.net/messages/edit?promo_id=16979

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Laws are created to be followed

by the poor.

Laws are made by the rich

to bring some order to exploitation.

The poor are the only law abiders in history.

When the poor make laws

the rich will be no more.

—Roque Dalton Presente!

(May 14, 1935 – Assassinated May 10, 1975)[1]

[1] Roque Dalton was a Salvadoran poet, essayist, journalist, political activist, and intellectual. He is considered one of Latin America's most compelling poets.

Poems:

http://cordite.org.au/translations/el-salvador-tragic/

About:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roque_Dalton

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

“In His Defense” The People vs. Kevin Cooper

A film by Kenneth A. Carlson

Teaser is now streaming at:

https://www.carlsonfilms.com

Posted by: Death Penalty Focus Blog, January 10, 2022

https://deathpenalty.org/teaser-for-a-kevin-cooper-documentary-is-now-streaming/?eType=EmailBlastContent&eId=1c7299ab-018c-4780-9e9d-54cab2541fa0

“In his Defense,” a documentary on the Kevin Cooper case, is in the works right now, and California filmmaker Kenneth Carlson has released a teaser for it on CarlsonFilms.com

Just over seven months ago, California Gov. Gavin Newsom ordered an independent investigation of Cooper’s death penalty case. At the time, he explained that, “In cases where the government seeks to impose the ultimate punishment of death, I need to be satisfied that all relevant evidence is carefully and fairly examined.”

That investigation is ongoing, with no word from any of the parties involved on its progress.

Cooper has been on death row since 1985 for the murder of four people in San Bernardino County in June 1983. Prosecutors said Cooper, who had escaped from a minimum-security prison and had been hiding out near the scene of the murder, killed Douglas and Peggy Ryen, their 10-year-old daughter, Jessica, and 10-year-old Chris Hughes, a friend who was spending the night at the Ryen’s. The lone survivor of the attack, eight-year-old Josh Ryen, was severely injured but survived.

For over 36 years, Cooper has insisted he is innocent, and there are serious questions about evidence that was missing, tampered with, destroyed, possibly planted, or hidden from the defense. There were multiple murder weapons, raising questions about how one man could use all of them, killing four people and seriously wounding one, in the amount of time the coroner estimated the murders took place.

The teaser alone gives a good overview of the case, and helps explain why so many believe Cooper was wrongfully convicted.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

New Legal Filing in Mumia’s Case

The following statement was issued January 4, 2022, regarding new legal filings by attorneys for Mumia Abu-Jamal.

Campaign to Bring Mumia Home

In her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, Zora Neale Hurston wrote, “There are years that ask questions, and years that answer.”

With continued pressure from below, 2022 will be the year that forces the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office and the Philly Police Department to answer questions about why they framed imprisoned radio journalist and veteran Black Panther Mumia Abu-Jamal. Abu-Jamal’s attorneys have filed a Pennsylvania Post Conviction Relief Act (PCRA) petition focused entirely on the six boxes of case files that were found in a storage room of the DA’s office in late December 2018, after the case being heard before Judge Leon Tucker in the Court of Common Pleas concluded. (tinyurl.com/zkyva464)

The new evidence contained in the boxes is damning, and we need to expose it. It reveals a pattern of misconduct and abuse of authority by the prosecution, including bribery of the state’s two key witnesses, as well as racist exclusion in jury selection—a violation of the landmark Supreme Court decision Batson v. Kentucky. The remedy for each or any of the claims in the petition is a new trial. The court may order a hearing on factual issues raised in the claims. If so, we won’t know for at least a month.

The new evidence includes a handwritten letter penned by Robert Chobert, the prosecution’s star witness. In it, Chobert demands to be paid money promised him by then-Prosecutor Joseph McGill. Other evidence includes notes written by McGill, prominently tracking the race of potential jurors for the purposes of excluding Black people from the jury, and letters and memoranda which reveal that the DA’s office sought to monitor, direct, and intervene in the outstanding prostitution charges against its other key witness Cynthia White.

Mumia Abu-Jamal was framed and convicted 40 years ago in 1982, during one of the most corrupt and racist periods in Philadelphia’s history—the era of cop-turned-mayor Frank Rizzo. It was a moment when the city’s police department, which worked intimately with the DA’s office, routinely engaged in homicidal violence against Black and Latinx detainees, corruption, bribery and tampering with evidence to obtain convictions.

In 1979, under pressure from civil rights activists, the Department of Justice filed an unprecedented lawsuit against the Philadelphia police department and detailed a culture of racist violence, widespread corruption and intimidation that targeted outspoken people like Mumia. Despite concurrent investigations by the FBI and Pennsylvania’s Attorney General and dozens of police convictions, the power and influence of the country’s largest police association, the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) prevailed.

Now, more than 40 years later, we’re still living with the failure to uproot these abuses. Philadelphia continues to fear the powerful FOP, even though it endorses cruelty, racism, and multiple injustices. A culture of fear permeates the “city of brotherly love.”

The contents of these boxes shine light on decades of white supremacy and rampant lawlessness in U.S. courts and prisons. They also hold enormous promise for Mumia’s freedom and challenge us to choose Love, Not PHEAR. (lovenotphear.com/) Stay tuned.

—Workers World, January 4, 2022

https://www.workers.org/2022/01/60925/

Pa. Supreme Court denies widow’s appeal to remove Philly DA from Abu-Jamal case

Abu Jamal was convicted by a jury of first-degree murder of Faulkner in 1982. Over the past four decades, five of his appeals have been quashed.

In 1989, the state’s highest court affirmed Abu-Jamal’s death penalty conviction, and in 2012, he was re-sentenced to life in prison.

Abu-Jamal, 66, remains in prison. He can appeal to the state Supreme Court, or he can file a new appeal.

KYW Newsradio reached out to Abu-Jamal’s attorneys for comment. They shared this statement in full:

“Today, the Superior Court concluded that it lacked jurisdiction to consider issues raised by Mr. Abu-Jamal in prior appeals. Two years ago, the Court of Common Pleas ordered reconsideration of these appeals finding evidence of an appearance of judicial bias when the appeals were first decided. We are disappointed in the Superior Court’s decision and are considering our next steps.

“While this case was pending in the Superior Court, the Commonwealth revealed, for the first time, previously undisclosed evidence related to Mr. Abu-Jamal’s case. That evidence includes a letter indicating that the Commonwealth promised its principal witness against Mr. Abu-Jamal money in connection with his testimony. In today’s decision, the Superior Court made clear that it was not adjudicating the issues raised by this new evidence. This new evidence is critical to any fair determination of the issues raised in this case, and we look forward to presenting it in court.”

https://www.audacy.com/kywnewsradio/news/local/pennsylvania-superior-court-rejects-mumia-abu-jamal-appeal-ron-castille

Questions and comments may be sent to: info@freedomarchives.org

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Sign our petition urging President Biden to grant clemency to Leonard Peltier.

https://www.freeleonardpeltier.com/petition

Email: contact@whoisleonardpeltier.info

Address: 116 W. Osborne Ave. Tampa, Florida 33603

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

How long will he still be with us? How long will the genocide continue?

By Michael Moore

American Indian Movement leader, Leonard Peltier, at 77 years of age, came down with Covid-19 this weekend. Upon hearing this, I broke down and cried. An innocent man, locked up behind bars for 44 years, Peltier is now America’s longest-held political prisoner. He suffers in prison tonight even though James Reynolds, one of the key federal prosecutors who sent Peltier off to life in prison in 1977, has written to President Biden and confessed to his role in the lies, deceit, racism and fake evidence that together resulted in locking up our country’s most well-known Native American civil rights leader. Just as South Africa imprisoned for more than 27 years its leading voice for freedom, Nelson Mandela, so too have we done the same to a leading voice and freedom fighter for the indigenous people of America. That’s not just me saying this. That’s Amnesty International saying it. They placed him on their political prisoner list years ago and continue to demand his release.

And it’s not just Amnesty leading the way. It’s the Pope who has demanded Leonard Peltier’s release. It’s the Dalai Lama, Jesse Jackson, and the President Pro-Tempore of the US Senate, Sen. Patrick Leahy. Before their deaths, Nelson Mandela, Mother Theresa and Bishop Desmond Tutu pleaded with the United States to free Leonard Peltier. A worldwide movement of millions have seen their demands fall on deaf ears.

And now the calls for Peltier to be granted clemency in DC have grown on Capitol Hill. Senator Brian Schatz (D-HI), the head of the Senate committee who oversees the Bureau of Indian Affairs, has also demanded Peltier be given his freedom. Numerous House Democrats have also written to Biden.

The time has come for our President to act; the same President who appointed the first-ever Native American cabinet member last year and who halted the building of the Keystone pipeline across Native lands. Surely Mr. Biden is capable of an urgent act of compassion for Leonard Peltier — especially considering that the prosecutor who put him away in 1977 now says Peltier is innocent, and that his US Attorney’s office corrupted the evidence to make sure Peltier didn’t get a fair trial. Why is this victim of our judicial system still in prison? And now he is sick with Covid.

For months Peltier has begged to get a Covid booster shot. Prison officials refused. The fact that he now has COVID-19 is a form of torture. A shame hangs over all of us. Should he now die, are we all not complicit in taking his life?

President Biden, let Leonard Peltier go. This is a gross injustice. You can end it. Reach deep into your Catholic faith, read what the Pope has begged you to do, and then do the right thing.

For those of you reading this, will you join me right now in appealing to President Biden to free Leonard Peltier? His health is in deep decline, he is the voice of his people — a people we owe so much to for massacring and imprisoning them for hundreds of years.

The way we do mass incarceration in the US is abominable. And Leonard Peltier is not the only political prisoner we have locked up. We have millions of Black and brown and poor people tonight in prison or on parole and probation — in large part because they are Black and brown and poor. THAT is a political act on our part. Corporate criminals and Trump run free. The damage they have done to so many Americans and people around the world must be dealt with.

This larger issue is one we MUST take on. For today, please join me in contacting the following to show them how many millions of us demand that Leonard Peltier has suffered enough and should be free:

President Joe Biden

Phone: 202-456-1111

E-mail: At this link

https://www.whitehouse.gov/contact/

Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland

Phone: 202-208-3100

E-mail: feedback@ios.doi.gov

Attorney General Merrick Garland

Phone: 202-514-2000

E-mail: At this link

https://www.justice.gov/doj/webform/your-message-department-justice

I’ll end with the final verse from the epic poem “American Names” by Stephen Vincent Benet:

I shall not rest quiet in Montparnasse.

I shall not lie easy at Winchelsea.

You may bury my body in Sussex grass,

You may bury my tongue at Champmedy.

I shall not be there. I shall rise and pass.

Bury my heart at Wounded Knee.

PS. Also — watch the brilliant 1992 documentary by Michael Apted and Robert Redford about the framing of Leonard Peltier— “Incident at Oglala”

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

The Moment

By Margaret Atwood*

The moment when, after many years

of hard work and a long voyage

you stand in the centre of your room,

house, half-acre, square mile, island, country,

knowing at last how you got there,

and say, I own this,

is the same moment when the trees unloose

their soft arms from around you,

the birds take back their language,

the cliffs fissure and collapse,

the air moves back from you like a wave

and you can't breathe.

No, they whisper. You own nothing.

You were a visitor, time after time

climbing the hill, planting the flag, proclaiming.

We never belonged to you.

You never found us.

It was always the other way round.

*Witten by the woman who wrote a novel about Christian fascists taking over the U.S. and enslaving women. Prescient!

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Union Membership—2021

Bureau of Labor Statistics

U.S. Department of Labor

For release 10:00 a.m. (ET) Thursday, January 20, 2022

Technical information:

(202) 691-6378 • cpsinfo@bls.gov • www.bls.gov/cps

Media contact:

(202) 691-5902 • PressOffice@bls.gov

In 2021, the number of wage and salary workers belonging to unions continued to decline (-241,000) to 14.0 million, and the percent who were members of unions—the union membership rate—was 10.3 percent, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. The rate is down from 10.8 percent in 2020—when the rate increased due to a disproportionately large decline in the total number of nonunion workers compared with the decline in the number of union members. The 2021 unionization rate is the same as the 2019 rate of 10.3 percent. In 1983, the first year for which comparable union data are available, the union membership rate was 20.1 percent and there were 17.7 million union workers.

These data on union membership are collected as part of the Current Population Survey (CPS), a monthly sample survey of about 60,000 eligible households that obtains information on employment and unemployment among the nation’s civilian noninstitutional population age 16 and over. For further information, see the Technical Note in this news release.

Highlights from the 2021 data:

• The union membership rate of public-sector workers (33.9 percent) continued to be more than five times higher than the rate of private-sector workers (6.1 percent). (See table 3.)

• The highest unionization rates were among workers in education, training, and library occupations (34.6 percent) and protective service occupations (33.3 percent). (See table 3.)

• Men continued to have a higher union membership rate (10.6 percent) than women (9.9 percent). The gap between union membership rates for men and women has narrowed considerably since 1983 (the earliest year for which comparable data are available), when rates for men and women were 24.7 percent and 14.6 percent, respectively. (See table 1.)

• Black workers remained more likely to be union members than White, Asian, or Hispanic workers. (See table 1.)

• Nonunion workers had median weekly earnings that were 83 percent of earnings for workers who were union members ($975 versus $1,169). (The comparisons of earnings in this news release are on a broad level and do not control for many factors that can be important in explaining earnings differences.) (See table 2.)

• Among states, Hawaii and New York continued to have the highest union membership rates (22.4 percent and 22.2 percent, respectively), while South Carolina and North Carolina continued to have the lowest (1.7 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively). (See table 5.)

Industry and Occupation of Union Members

In 2021, 7.0 million employees in the public sector belonged to unions, the same as in the private sector. (See table 3.)

Union membership decreased by 191,000 over the year in the public sector. The public-sector union membership rate declined by 0.9 percentage point in 2021 to 33.9 percent, following an increase of 1.2 percentage points in 2020. In 2021, the union membership rate continued to be highest in local government (40.2 percent), which employs many workers in heavily unionized occupations, such as police officers, firefighters, and teachers.

The number of union workers employed in the private sector changed little over the year. However, the number of private-sector nonunion workers increased in 2021. The private-sector unionization rate declined by 0.2 percentage point in 2021 to 6.1 percent, slightly lower than its 2019 rate of 6.2 percent. Industries with high unionization rates included utilities (19.7 percent), motion pictures and sound recording industries (17.3 percent), and transportation and warehousing (14.7 percent). Low unionization rates occurred in finance (1.2 percent), professional and technical services (1.2 percent), food services and drinking places (1.2 percent), and insurance (1.5 percent).

Among occupational groups, the highest unionization rates in 2021 were in education, training, and library occupations (34.6 percent) and protective service occupations (33.3 percent). Unionization rates were lowest in food preparation and serving related occupations (3.1 percent); sales and related occupations (3.3 percent); computer and mathematical occupations (3.7 percent); personal care and service occupations (3.9 percent); and farming, fishing, and forestry occupations (4.0 percent).

Selected Characteristics of Union Members

In 2021, the number of men who were union members, at 7.5 million, changed little, while the number of women who were union members declined by 182,000 to 6.5 million. The unionization rate for men decreased by 0.4 percentage point over the year to 10.6 percent. In 2021, women’s union membership rate declined by 0.6 percentage point to 9.9 percent. The 2021 decreases in union membership rates for men and women reflect increases in the total number of nonunion workers. The rate for men is below the 2019 rate (10.8 percent), while the rate for women is above the 2019 rate (9.7 percent). (See table 1.)

Among major race and ethnicity groups, Black workers continued to have a higher union membership rate in 2021 (11.5 percent) than White workers (10.3 percent), Asian workers (7.7 percent), and Hispanic workers (9.0 percent). The union membership rate declined by 0.4 percentage point for White workers, by 0.8 percentage point for Black workers, by 1.2 percentage points for Asian workers, and by 0.8 percentage point for Hispanic workers. The 2021 rates for Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics are little or no different from 2019, while the rate for Asians is lower.

By age, workers ages 45 to 54 had the highest union membership rate in 2021, at 13.1 percent. Younger workers—those ages 16 to 24—had the lowest union membership rate, at 4.2 percent.

In 2021, the union membership rate for full-time workers (11.1 percent) continued to be considerably higher than that for part-time workers (6.1 percent).

Union Representation

In 2021, 15.8 million wage and salary workers were represented by a union, 137,000 less than in 2020. The percentage of workers represented by a union was 11.6 percent, down by 0.5 percentage point from 2020 but the same as in 2019. Workers represented by a union include both union members (14.0 million) and workers who report no union affiliation but whose jobs are covered by a union contract (1.8 million). (See table 1.)

Earnings

Among full-time wage and salary workers, union members had median usual weekly earnings of $1,169 in 2021, while those who were not union members had median weekly earnings of $975. In addition to coverage by a collective bargaining agreement, these earnings differences reflect a variety of influences, including variations in the distributions of union members and nonunion employees by occupation, industry, age, firm size, or geographic region. (See tables 2 and 4.)

Union Membership by State

In 2021, 30 states and the District of Columbia had union membership rates below that of the U.S. average, 10.3 percent, while 20 states had rates above it. All states in both the East South Central and West South Central divisions had union membership rates below the national average, while all states in both the Middle Atlantic and Pacific divisions had rates above it. (See table 5 and chart 1.)

Ten states had union membership rates below 5.0 percent in 2021. South Carolina had the lowest rate (1.7 percent), followed by North Carolina (2.6 percent) and Utah (3.5 percent). Two states had union membership rates over 20.0 percent in 2021: Hawaii (22.4 percent) and New York (22.2 percent).

In 2021, about 30 percent of the 14.0 million union members lived in just two states (California at 2.5 million and New York at 1.7 million). However, these states accounted for about 17 percent of wage and salary employment nationally.

Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic Impact on 2021 Union Members Data

Union membership data for 2021 continue to reflect the impact on the labor market of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Comparisons with union membership measures for 2020, including metrics such as the union membership rate and median usual weekly earnings, should be interpreted with caution. The onset of the pandemic in 2020 led to an increase in the unionization rate due to a disproportionately large decline in the number of nonunion workers compared with the decline in the number of union members. The decrease in the rate in 2021 reflects a large gain in the number of nonunion workers and a decrease in the number of union workers. More information on labor market developments in recent months is available at:

www.bls.gov/covid19/effects-of-covid-19-pandemic-and- response-on-the-employment-situation-news-release.htm.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Resources for Resisting Federal Repression

Since June of 2020, activists have been subjected to an increasingly aggressive crackdown on protests by federal law enforcement. The federal response to the movement for Black Lives has included federal criminal charges for activists, door knocks by federal law enforcement agents, and increased use of federal troops to violently police protests.

The NLG National Office is releasing this resource page for activists who are resisting federal repression. It includes a link to our emergency hotline numbers, as well as our library of Know-Your-Rights materials, our recent federal repression webinar, and a list of some of our recommended resources for activists. We will continue to update this page.

Please visit the NLG Mass Defense Program page for general protest-related legal support hotlines run by NLG chapters.

Emergency Hotlines

If you are contacted by federal law enforcement you should exercise all of your rights. It is always advisable to speak to an attorney before responding to federal authorities.

State and Local Hotlines

If you have been contacted by the FBI or other federal law enforcement, in one of the following areas, you may be able to get help or information from one of these local NLG hotlines for:

- Portland, Oregon: (833) 680-1312

- San Francisco, California: (415) 285-1041 or fbi_hotline@nlgsf.org

- Seattle, Washington: (206) 658-7963

National Hotline

If you are located in an area with no hotline, you can call the following number:

Know Your Rights Materials

The NLG maintains a library of basic Know-Your-Rights guides.

- Know Your Rights During Covid-19

- You Have The Right To Remain Silent: A Know Your Rights Guide for Encounters with Law Enforcement

- Operation Backfire: For Environmental and Animal Rights Activists

WEBINAR: Federal Repression of Activists & Their Lawyers: Legal & Ethical Strategies to Defend Our Movements: presented by NLG-NYC and NLG National Office

We also recommend the following resources:

Center for Constitutional Rights

Civil Liberties Defense Center

- Grand Juries: Slideshow

Grand Jury Resistance Project

Katya Komisaruk

Movement for Black Lives Legal Resources

Tilted Scales Collective

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

The warming of the earth, combined with the exhausting nature of the game, is raising questions about the future of the second most popular sport in the world.

By Jeré Longman and Karan Deep Singh, Aug. 4, 2022

Jeré Longman reported from Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago; and Karan Deep Singh from New Delhi.

England’s Ben Stokes walked past his teammate Jos Buttler after losing his wicket. Credit...Lee Smith/Action Images Via Reuters

The joke is that if you want it to rain during this wetter-than-usual summer in the Caribbean, just start a cricket match.

Beneath the humor is seemingly tacit agreement with the assertion in a 2018 climate report that of all the major outdoor sports that rely on fields, or pitches, “cricket will be hardest hit by climate change.”

By some measures, cricket is the world’s second most popular sport, behind soccer, with two billion to three billion fans. And it is most widely embraced in countries like India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and South Africa and in the West Indies, which are also among the places most vulnerable to the intense heat, rain, flooding, drought, hurricanes, wildfires and sea level rise linked to human-caused emissions of greenhouse gases.

Cricket in developed nations like England and Australia has also been affected as heat waves become hotter, more frequent and longer lasting. Warm air can hold more moisture, resulting in heavier rainstorms. Twenty of the 21 warmest years recorded have occurred since 2000.

This year, the sport has faced the hottest spring on the Indian subcontinent in more than a century of record keeping and the hottest day ever in Britain. In June, when the West Indies — a combined team from mainly English-speaking countries in the Caribbean — arrived to play three matches in Multan, Pakistan, the temperature reached 111 degrees Fahrenheit, above average even for one of the hottest places on earth.

“It honestly felt like you were opening an oven,” said Akeal Hosein, 29, of the West Indies, who with his teammates wore ice vests during breaks in play.

Heat is hardly the only concern for cricket players. Like the roughly similar pitching and batting sport of baseball, cricket cannot easily be played in the rain. In July, the West Indies abandoned a match in Dominica and shortened others in Guyana and Trinidad because of rain and waterlogged fields.

An eight-match series between the West Indies and India concludes Saturday and Sunday in South Florida as the height of hurricane season approaches in the Gulf and the Atlantic. In 2017, two Category 5 storms, Irma and Maria, damaged cricket stadiums in five countries in the Caribbean.

Matches can last up to five days. Even one-day matches can extend in blistering conditions for seven hours or more. While rain cleared July 22 for the 9:30 a.m. opening of the West Indies-India series in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, players still had to contend with eight hours of sun at Queen’s Park Oval in temperatures that reached the low 90s with 60-plus percent humidity.

According to a 2019 report on cricket and climate change, a professional batsman playing over a day can generate heat equivalent to running a marathon. While marathon runners help dissipate heat by wearing shorts and singlets, in cricket the wearing of pads, gloves and a helmet restricts the ability to evaporate sweat in hot, humid conditions often lacking shade.

“It’s pretty evident that travel plans are being disrupted because of weather conditions, along with the scheduling of matches, because of rainfall, smoke, pollution, dust and heat,” said Daren Ganga, 43, a commentator and former West Indies captain who studies the impact of climate change on sport in affiliation with the University of the West Indies.

“Action needs to be taken for us to manage this situation,” Ganga said, “because I think we’ve gone beyond the tipping point in some areas. We still have the opportunity to pull things back in other areas.”

The International Cricket Council, the sport’s governing body, has not yet signed on to a United Nations sports and climate initiative. Its goal is for global sports organizations to reduce their carbon footprint to net-zero emissions by 2050 and to inspire the public to consider the issue urgently. While Australia has implemented heat guidelines, and more water breaks are generally permitted during matches, there is no global policy for play in extreme weather. The cricket council did not respond to a request for comment.

“This is like stick your head in the sand denial,” David Goldblatt, the British author of a 2020 report on sport and climate change, said of the council. “Cricket really needs to get its act together. A whole bunch of trouble is not really far away.”

A suggestion in the 2019 climate report that players be allowed to wear shorts instead of trousers to keep cool in excessive heat may seem like a common-sense idea. But it has not gone over well with the starchy customs of international cricket or seemingly with many players, who say their legs would be even more susceptible to brush burns and bruises from sliding and diving on hard fields.

“My two knees are already gone,” said India’s Yuzvendra Chahal, who is 32.

Still, questions are being raised inside the sport and out about the sustainability of cricket amid the extremes of climate and the exhausting scheduling of various formats of the game. The English star Ben Stokes retired on July 19 from the one-day international format, saying, “We are not cars where you can fill us up with petrol and let us go.”

Coincidentally, Stokes’s retirement came as Britain recorded its hottest day ever, with temperatures rising for the first time above 40 degrees Celsius, or 104 degrees Fahrenheit. As climate scientists said such heat could become the new normal, England hosted a daylong cricket match with South Africa in the modestly cooler northeastern city of Durham. Extra water breaks, ice packs and beach-style umbrellas were employed to keep the players cool. Even with those precautions, Matthew Potts of England left the match, exhausted.

Aiden Markram of South Africa was photographed with an ice bag on his head and another on his neck, his face in apparent distress, as if he had been in a heavyweight fight. Some fans were reported to have fainted or sought medical attention, while many others scrambled for thin slices of shade.

On June 9, South Africa also endured taxing conditions when it faced India in the heat, humidity and pollution of New Delhi. The heat index was 110 degrees Fahrenheit for an evening match. A section of the stadium was transformed into a cooling zone for spectators, with curtains, chairs and misting fans attached to plastic tubs of water.

“We are used to it,” said Shikhar Dhawan, 36, one of India’s captains. “I don’t really focus on the heat because if I start thinking about it too much I will start feeling it more.”

In India, cricket players are as popular as Bollywood actors. Even in sauna-like conditions, more than 30,000 spectators attended the match in New Delhi. “It feels great. Who cares about the heat?” said Saksham Mehndiratta, 17, attending his first match with his father since the coronavirus pandemic began.

After watching some spectacular batting, his father, Naresh, said, “This chills me down.”

South Africa, though, was taking no chances after a tour of India in 2015, when eight players and two members of the coaching and support staff were hospitalized in the southern city of Chennai by what officials said were the combined effects of food poisoning and heat exhaustion.

“It was mayhem,” said Craig Govender, a physiotherapist for the South African team.

For South Africa’s recent tour, Govender took along inflatable tubs to cool players’ feet; electrolyte capsules for mealtimes; slushies of ice and magnesium; and ice towels for the shoulders, face and back. South Africa’s uniforms were ventilated behind the knees, along the seams and under the armpits. Players were weighed before and after training sessions. The color of their urine was monitored to guard against dehydration. During the June 9 match, some players jumped into ice baths to cool down.

“Global warming is already wreaking havoc on our sport,” Pat Cummins, the captain of Australia’s test cricket team, which plays five-day matches, wrote in February in The Guardian newspaper of Britain.

In 2017, Sri Lankan players wore masks and had oxygen canisters available in the dressing room to counter the heavy pollution during a match in New Delhi. Some players vomited on the field.

In 2018, the English captain Joe Root was hospitalized with gastrointestinal issues, severe dehydration and heat stress during the famed, five-day Ashes test in Sydney, Australia. At one point, a heat-index tracker registered 57.6 degrees Celsius, or 135.7 Fahrenheit.

The incident led Tony Irish, then the head of the Federation of International Cricketers’ Association, to ask, “What will it take — a player to collapse on the field?” before cricket’s governing body implemented an extreme heat policy.

Also in 2018, India’s players were asked to limit showers to two minutes while playing in Cape Town during an extended drought there that caused the cancellation of club and school cricket.

In 2019, the air in Sydney became so smoky during a bush fire crisis that the Australian player Steve O’Keefe said it felt like “smoking 80 cigarettes a day.”

Climate change has touched every aspect of cricket from batting and bowling strategy to concerns by groundskeepers about seed germination, pests and fungal disease. Even Lord’s, the venerable cricket ground in London, has been forced at times to relax its fusty dress code, most recently in mid-July when patrons were not required to wear jackets in the unprecedented heat.

Athletes are being asked “to compete in environments that are becoming too hostile to human physiology,” Russell Seymour, a pioneer in sustainability at Lord’s, wrote last year in a climate report. “Our love and appetite for sport risks straying into brutality.”

To be fair, some actions have been taken to help mitigate climate change. Matches sometimes start later in the day or are rescheduled. Cummins, the Australian captain, has begun an initiative to have solar panels installed on the roofs of cricket clubs there. Lord’s operates fully on wind-powered electricity. The National Green Tribunal of India, a specialized body that addresses environmental concerns, has ruled that treated waste water should be used to irrigate cricket fields instead of drinkable ground water, which is in short supply.

Players on the Royal Challengers Bangalore club of the Indian Premier League wear green uniforms for some matches to heighten environmental awareness. Team members appeared in a climate video during a devastating heat wave this spring, which included this sobering fact: “This has been the hottest temperature the country has faced in 122 years.”

Yet some in the cricket world counter that climate change cannot be expected to be the most immediate concern in developing nations, where the basics of daily life can be a struggle. And countries like India and Pakistan, where cricket is wildly popular, are among the least responsible for climate change. One hears the frequent admonishment that rich, developed nations that emit the largest amount of greenhouse gases must also do their share to lower those emissions.

“In the U.S., people are flying on private jets while they’re asking us not to use plastic straws,” said Dario Barthley, a spokesman for the West Indies team.

Kitty Bennett contributed research.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Amid a citywide homicide spike, officials believe the recent deaths of four Muslim men are connected, leading to fear in a place where many immigrants and refugees had felt at home.

By Simon Romero, Neelam Bohra and Nicholas Bogel-Burroughs, Aug. 9, 2022

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/09/us/albuquerque-muslim-killings.html

Three of the four Muslim men killed in the shootings that the police say are related belonged to the Islamic Center of New Mexico in Albuquerque. Adria Malcolm for The New York Times

Naeem Hussain was the third Muslim man killed in recent weeks, and the fourth since November.

ALBUQUERQUE — Tahir Gauba attended funerals on Friday for two members of Albuquerque’s largest mosque, victims in a spate of apparently targeted killings that have shaken this Southwestern city, which in recent years has welcomed a growing community of immigrants and refugees.

Afterward at the mosque, Mr. Gauba ran into Naeem Hussain, a 25-year-old from Pakistan. “Naeem asked me, ‘Brother, what’s happening in Albuquerque?’” said Mr. Gauba, 43, who also came to New Mexico from Pakistan. “I told him, ‘It’s crazy right now, don’t leave your house if you don’t have to.’”

Hours later, Mr. Hussain was also dead, shot in a parking lot. It was the third killing of a Muslim man in recent weeks, and the fourth since November.

The killings, which law enforcement officials believe are connected, have raised alarm in a city that the authorities had sought to shape into a haven for immigrants and refugees, including hundreds who resettled from Afghanistan in the past year, since the withdrawal of the U.S. military presence there.

The possibility that someone could now be targeting Muslims, in a city already reeling from a harrowing spike in murders, has many in Albuquerque asking how this could happen.

One of the victims, Muhammad Afzaal Hussain, 27, moved from Pakistan to attend the University of New Mexico. He had become president of its graduate student association before going into city planning. Another, Aftab Hussein, 41, worked at a local cafe.

Naeem Hussain, the 25-year-old who was killed on Friday, had started his own trucking business and become a U.S. citizen just weeks earlier. The recent killings were preceded by the fatal shooting in November of Mohammad Ahmadi, 62, a Muslim immigrant from Afghanistan, who was attacked outside the grocery store that he owned with his brother.

“There are recent arrivals who are fearful, and there are people who are U.S.-born Muslims who are also are on edge,” said Michelle Melendez, director of the city’s Office of Equity and Inclusion. “The victims are everything from professionals to students to working-class people.”

Scrambling to respond, the Albuquerque Police Department has begun bolstering patrols around the businesses and places of worship that serve as gathering places for the city’s Muslims, estimated to number from 5,000 to 10,000 in a city of over half a million.

In a plea for help from the public, the police over the weekend released a photo of a car, thought to be a dark gray Volkswagen sedan, which they believe was used in the killings.

The fatal shootings came amid a string of murders in the city, explaining, perhaps, why it didn’t seem unusual for the first two killings of Muslim men to go relatively unnoticed.

In 2021, 116 people in the city were killed, according to crime statistics from the Albuquerque Police Department, which exclude justified or negligent homicides. It was the city’s deadliest year on record; one person was killed an average of every three days in November 2021, when Mr. Ahmadi was found dead.

Things have only become worse this year. As of Monday, homicides are on pace to reach 131, surpassing last year by more than a dozen. That’s more than double the average number of homicides from 2010 to 2020, when the city recorded about 53 killings each year.

At the same time, Albuquerque, like other cities around the country, has struggled to fill vacancies in its police force. Since 2014, the department has been under a settlement agreement with the Justice Department to improve its practices, reached after accusations of civil rights violations and excessive force.

Police officials have remained largely quiet about their investigation into the recent killings beyond asking for help in finding the sedan and stating that they believe one individual carried out the acts.

“While we won’t go into why we think that, there’s one strong commonality in all of our victims: their race and religion,” Kyle Hartsock, deputy commander of the department’s Criminal Investigations Division, said in a statement. “We are taking this very serious, and we want the public’s help in identifying this cowardly individual.”

Before going into truck driving, Naeem Hussain, the most recent victim, had worked as a case manager for Lutheran Family Services, helping refugees. It was in the parking lot of that organization where Mr. Hussain, a Pashto speaker who had family roots in Pakistan and Afghanistan, was killed while in his car.

Ahmad Assed, who grew up in Albuquerque and is now president of the city’s largest mosque, the Islamic Center of New Mexico, described the community as a “welcoming melting pot.” He almost never felt that he stuck out as a Muslim, he said, until a woman was arrested and accused of trying to burn down the mosque last year.

Mr. Assed, who was born in Dearborn, Mich., said that even with increasing xenophobia after the Sept. 11 attacks, the city seemed to continue to treat the Muslim community with respect, regardless of faith and nationalities.

Now many Muslims in the city feel like targets, and fear is even driving some people to make plans to leave New Mexico.

Indeed, the killings have jolted an increasingly diverse city, where immigration, largely from Mexico and other Latin American countries, is a major source of population growth and integral to the city’s history. Immigrants from the Middle East, including Muslims and Christians from Lebanon and Syria, put down stakes in Albuquerque and other parts of New Mexico in the late 19th century.

The city gradually saw a new wave of Muslim immigrants in recent decades, with many coming to study at the University of New Mexico. A group of Muslim students came together in the mid-1980s to form the Islamic Center of New Mexico, which the three most recent victims attended.

Many in the city’s Muslim community come from Pakistan and Afghanistan, while others are from countries including India, Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Sri Lanka. During the Trump administration, when concerns grew over bigotry directed against Muslims, officials passed a bill affirming Albuquerque’s status as an “immigrant friendly” city. It restricted federal immigration agents from entering city-operated facilities and city employees from collecting immigration status information.

At least 300 Afghan refugees have arrived in Albuquerque over the past year, bolstering a growing community reflected today by at least eight different places of worship for Muslims. Albuquerque strengthened outreach efforts through translators speaking Arabic, Dari, Farsi, Urdu and Pashto — languages that officials have prioritized in recent days when sharing information about the killings.

Although Muslims in the United States faced violence and discrimination after Sept. 11 and during Donald J. Trump’s presidential campaign, the apparent serial nature of the attacks in Albuquerque — and the stubborn mystery of who is responsible — is uniquely disconcerting, said Sumayyah Waheed, senior policy counsel at Muslim Advocates, a civil rights group.

“I can’t think of any incident like this,” she said.

Ms. Waheed said it was concerning that the police in Albuquerque had apparently made a possible connection between the attacks only after three Muslim men were killed.

Statistics from the Albuquerque Police Department show that the racial breakdown of its employees, including officers and civilians, are roughly in line with that of the city, where about half of the residents are Latino and 38 percent are white. As of June 2021, there were 17 Asian employees out of nearly 1,480 people in the department. It is unclear how many officers are Muslim, and a spokesman said the department did not collect data on religious affiliation.

Although Naeem Hussain’s death on Friday heightened the concerns of his community, Ehsan Shahalami, his brother-in-law, said the killing came as a shock.

“There was never any indication of him feeling threatened or being scared of anything,” Mr. Shahalami said. “On the contrary, he was very fond of Albuquerque. He wanted to give back to the place that took him in.”

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

The men were convicted of federal hate crimes after state murder convictions in 2021. Their lawyers tried without success to have part of their sentences served in federal prison.

By Richard Fausset, Aug. 8, 2022

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/08/us/arbery-killer-sentencing.html

Ahmaud Arbery

ATLANTA — Before the three men convicted of murdering Ahmaud Arbery were sentenced on Monday on federal hate crime charges, they asked a judge to consider not only the length of the sentences, but also the location, with one lawyer arguing that if her client went straight to Georgia’s dangerous state prison system, he would be subject to “vigilante justice.”

The men did not get what they asked for.

U.S. District Court Judge Lisa Godbey Wood said she had “neither the authority nor the inclination” to send the three white men to federal prison in lieu of the Georgia prison system, where safety issues are so dire that they are the subject of an investigation by the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Justice Department.

Judge Wood said that the men would go to state prison first, because they were first prosecuted for murder by state authorities. At the same time, the judge handed down severe sentences to the men for their federal crimes, which included the hate-crime charge of “interference with rights,” and attempted kidnapping.

Travis McMichael, the 36-year-old who fired on Mr. Arbery with a shotgun, was given a life sentence. So was Mr. McMichael’s 66-year-old father, Gregory McMichael. Their neighbor William Bryan, 52 — who joined the McMichaels in chasing Mr. Arbery, a 25-year-old Black man, through their neighborhood on a Sunday afternoon in February 2020 — received a sentence of 35 years.

The federal sentences will run concurrently with the life sentences stemming from each man’s murder conviction in state court, for which only Mr. Bryan is deemed eligible for parole — and then only after 30 years.

In a statement, Attorney General Merrick B. Garland said that the sentences “make clear that hate crimes have no place in our country, and that the department will be unrelenting in our efforts to hold accountable those who perpetrate them.”

The courtroom drama on Monday — which featured rare words of remorse in open court from Mr. Bryan and the elder Mr. McMichael — closed a chapter “in an excruciatingly painful journey” as the federal prosecutor Tara M. Lyons put it, “for Ahmaud Arbery’s family and for an entire nation that has wept for Ahmaud along with his loved ones.”

Long federal sentences were expected for the three men after their convictions in Judge Wood’s courtroom in February. The idea that they should be able to serve at least some of their time in federal prison, as opposed to Georgia’s prison system, became an emotional flash point when it was first offered up in proposed plea deals for the McMichaels that were presented to the court in January; it was eventually rejected by Judge Wood.

In a filing last week, Amy Lee Copeland, Travis McMichael’s lawyer, wrote that her client had received “hundreds of threats,” including “statements that his image has been circulated through the state prison system on contraband cellphones, that people are ‘waiting for him,’ that he should not go into the yard, and that correctional officers have promised a willingness (whether for pay or for free) to keep certain doors unlocked and backs turned to allow inmates to harm him.”

But Mr. Arbery’s family members came to the federal courthouse in Brunswick, Ga., on Monday and argued that the three men deserved no special treatment after their own notorious acts of vigilantism against Mr. Arbery.

“These three devils have broken my heart into pieces,” Marcus Arbery Sr., Mr. Arbery’s father, said in court on Monday. He added that he hoped the men would “rot in the state prison.”

In three separate hearings, the defense lawyers for the three men asked for at least the first part of their clients’ terms to be served in the federal system. Ms. Copeland noted the “rich irony” that her client was concerned about vigilante violence. But she argued for a “cooling off” period in federal prison to last for the duration of the appeals process. Putting her client in state prison now, she said, would “effectively” result in “a back-door death penalty.”

In announcing their investigation, federal officials said the safety problems in Georgia’s prison system had been compounded by staffing shortages, training issues and other factors. Ms. Copeland cited an analysis from Georgia Public Broadcasting that found that 53 homicides had occurred in Georgia’s state prisons in 2020 and 2021.

The McMichaels and Mr. Bryan are currently being held in a local jail, the Glynn County Detention Center, where they have been since they were arrested in May 2020. They had walked free for weeks after Travis McMichael shot Mr. Arbery at close range with a shotgun.

The fatal shooting came after the men, in a pair of pickup trucks, chased Mr. Arbery, who was on foot, through their suburban neighborhood of Satilla Shores, just outside of Brunswick. The chase, and the killing, were captured on video that was widely circulated on the internet, sparking outrage worldwide and assertions from civil rights leaders that Mr. Arbery had been subject to a modern-day lynching.

Moments before the chase, Mr. Arbery had been inside a house under construction; the McMichaels had suspected him of committing a string of property crimes. Mr. Arbery’s relatives said that Mr. Arbery, an avid runner, had been out for a Sunday jog. In court proceedings, prosecutors argued that all three defendants harbored racial animus toward Black people.

In court on Monday, A.J. Balbo, the lawyer for Gregory McMichael, asked for leniency, noting that his client suffered from heart problems and bouts of depression and anxiety. The lawyer for Mr. Bryan, J. Pete Theodocion, noted that his client, unlike the McMichaels, had not grabbed a gun when he joined the chase. Prosecutors noted, however, that Mr. Bryan had used his truck to block Mr. Arbery as he tried to run out of the neighborhood.

Judge Wood said she had spent a long time thinking about the appropriate sentences for the men. At one point, she referred to the February 2022 federal trial that she presided over, in which all three men were found guilty of federal hate crimes.

It had been a fair trial, Judge Wood said — “the kind of trial that Ahmaud Arbery did not receive before he was shot and killed.”

The three men did not take the stand during their trials. But on Monday, Mr. Bryan apologized to Mr. Arbery’s family: “I never intended any harm to him,” he said.

Travis McMichael declined to address the court. But his father spoke before his sentencing. “The loss that you’ve endured is beyond description,” Gregory McMichael said to the Arbery family. “I’m sure that my words mean very little to you. But I want to assure you, I never wanted any of this to happen.”

The McMichaels were each given extra sentences, to run consecutively rather than concurrently, for their use of firearms in the incident. Mr. Bryan was technically given 447 months, with 27 months off for time served.

“By the time you’ve served your federal sentence, you will be close to 90 years old,” the judge said to Mr. Bryan. “But, again, Mr. Arbery never got the chance to be 26.”

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

The family of Anton Black, who died after being held face down for about six minutes during a 2018 encounter, partly settled their lawsuit against three Eastern Shore Police Departments.

By Eduardo Medina, Aug. 8, 2022

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/08/us/anton-black-maryland-police-settlement.html

An image of Anton Black, right, who died in police custody in 2018. Credit...Schaun Champion for The New York Times

Three towns on Maryland’s Eastern Shore have agreed to pay $5 million to the family of a Black teenager who was killed in an encounter with police officers in 2018, lawyers for the family said on Monday.

The announcement of a partial settlement in the federal lawsuit brought by the family of Anton Black came nearly four years after Mr. Black, a 19-year-old former star high school athlete with a nascent modeling career, died after being restrained by three police officers, who held him face down for about six minutes, pinning his shoulder, legs and arms, according to the lawsuit. As part of the agreement, the towns also agreed to make changes in how their Police Departments train officers to prevent similar deaths.

Mr. Black’s death drew comparisons to the May 2020 killing of George Floyd, who was pinned to the ground under the knee of Derek Chauvin, a white former Minneapolis police officer, for more than nine minutes.

After local prosecutors did not pursue charges in the death, Mr. Black’s family filed a lawsuit in U.S. District Court in Baltimore in December 2020, arguing that the police officers — all of whom were white — from Police Departments in the towns of Centreville, Greensboro and Ridgely had used excessive force on Sept. 15, 2018. The lawsuit also contended that the officers tried to cover up an unjustified killing by claiming that Mr. Black was under the influence of marijuana laced with another drug and had exhibited “superhuman” strength.

An autopsy report released four months later by the state’s medical examiner at the time, David Fowler, blamed congenital heart abnormalities for Mr. Black’s death and classified the death as an accident, saying there was no evidence that the police officers’ actions had played a role. The litigation by Mr. Black's family against the medical examiner’s office and Mr. Fowler — also defendants in their lawsuit — is continuing.

Jennell Black, Mr. Black’s mother, said in a statement that “there are no words to describe the immense hurt that I will always feel when I think back on that tragic day, when I think of my son.”

“No family should have to go through what we went through,” she added. “I hope the reforms within the Police Departments will save lives and prevent any family from feeling the pain we feel every day.”

In addition to the three towns, the partial settlement of the lawsuit resolved the family’s claims against several people in the towns, including Thomas Webster IV, a former Greensboro police officer; Michael Petyo, the former chief of the Greensboro Police Department; Gary Manos, the former chief of the Ridgely Police Department; and Dennis Lannon, a former Centreville police officer.

The men could not be reached or did not immediately respond to calls seeking comment on Monday night.

The lawyers representing the three towns — Patrick W. Thomas, Sharon M. VanEmburgh and Lyndsey Ryan — did not immediately respond to emails or calls seeking comment on Monday. The attorney general’s office, which is representing the medical examiner’s officer, did not immediately respond to a call seeking comment on Monday.

In the summer of 2018, Mr. Black developed mental health issues and began behaving erratically, according to the lawsuit. He was eventually found to have bipolar disorder.

On Sept. 15, 2018, a woman called 911 after seeing Mr. Black roughhousing with a 12-year-old boy, the lawsuit says. The officers who arrived used a Taser on Mr. Black and pinned him down near his mother’s home in Greensboro, the lawsuit says.

While he was being held down, Mr. Black told his mother, “I love you,” and cried out, “Please,” according to the lawsuit, which cites body camera footage from the officers.

Moments later, after his mother noticed that Mr. Black was “turning dark,” emergency medical workers tried to resuscitate him, but he died after being taken to a hospital, the lawsuit says.