April 9, San Francisco Bay Area, 12:00 P.M.

Sproul Plaza UC Berkeley campus

Friday April 8: Take up the green bandana, the symbol of the increasingly victorious Green Wave in-the-streets fight for abortion rights across Latin America. Campuses, cultural events, social media and workplaces must be awash in GREEN (bandanas, banners, chalk, stickers, etc.). Everyone must show where they stand!

Saturday April 9: Take to the streets in mass protest! With serious determination and rebellious joy, we will wake tens- and hundreds-of-thousands of others up to the emergency and inspire growing numbers to join us.

From there, we will rally even greater numbers in growing nonviolent protests and creative GREEN WAVE resistance, aiming to bring society to a halt and force our demand – that women not be slammed backwards – to be reckoned with and acted upon by every institution in society. NOW is the time to stand up, together, as if our lives depend upon it—for, in fact, they do.

(Find a protest near you or host your own. DM us on social media / 973 544 8228 /

email to info@RiseUp4AbortionRights.org

· New York City 2:00 pm Union Square (@14th Street) RSVP + Share

· Atlanta 2:00 pm Midtown MARTA 41 10th Street NE RSVP + Share

· Austin 12 noon rally at Republic Square Park 422 Guadalupe

1:00 pm march to Governor’s mansion RSVP + Share

· Boston 2:00 pm Boston Commons Free Speech Area across from Massachusetts State House RSVP + Share

· Cleveland 2:00 pm Market Square 25th & Lorain Avenue RSVP + Share

· Chicago 2:00 pm Wrigley Square at Millennium Park, North Michigan Avenue RSVP + Share

· Detroit 3:00 pm W. Warren & Woodward 1 W. Warren Avenue RSVP + Share

· Los Angeles 2:00 pm Hollywood & Highland RSVP + Share

· San Francisco Bay Area 12:00 pm Sproul Plaza UC Berkeley campus, Berkeley RSVP + Share

· Seattle 1:00 pm Seattle Central College Plaza RSVP + Share

RefuseFascism.org national team

(917) 407-1286

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

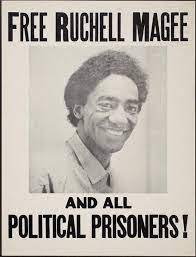

This March 19th webinar for Ruchell “Cinque” Magee on his 83rd birthday was a terrific event full of information and plans for building the campaign to Free Ruchell Magee. Two of the featured speakers also spoke at the February 1 webinar for International workers’ action to free Mumia and all anti-racist, anti-imperialist Freedom Fighters—Jalil Muntaqim (who was serving time at San Quentin State Prison in a cell next to Ruchell!) and Angela Davis (who was a co-defendant of Ruchell’s!) A 50 year+ struggle!

Below are two ways to stream this historic webinar sent by the webinar organizers.

Here is the YouTube link to view Saturday's recording:

https://youtu.be/4u5XJzhv9Hc

Here is the link to the Facebook upload:

https://fb.watch/bTMr6PTuHS/

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

After The Revolution

By David Rovics

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VdodojUTMG0

It was a time I'll always remember

Because I could never forget

How reality fell down around us

Like some Western movie set

And once the dust all settled

The sun shone so bright

And a great calm took over us

Like it was all gonna be alright

That's how it felt to be alive

After the revolution

From Groton to Tacoma

On many a factory floor

The workers talked of solidarity

And refused to build weapons of war

No more will we make missiles

We're gonna do something different

And for the first time

Their children were proud of their parents

And somewhere in Gaza a little boy smiled and cried

After the revolution

Prison doors swung open

And mothers hugged their sons

The Liberty Bell was ringing

When the cops put down their guns

A million innocent people

Lit up in the springtime air

And Mumia and Leonard and Sarah Jane Olson

Took a walk in Tompkins Square

And they talked about what they'd do now

After the revolution

The debts were all forgiven

In all the neo-colonies

And the soldiers left their bases

Went back to their families

And a non-aggression treaty

Was signed with every sovereign state

And all the terrorist groups disbanded

With no empire left to hate

And they all started planting olive trees

After the revolution

George Bush and Henry Kissinger

Were sent off to the World Court

Their plans for global domination

Were pre-emptively cut short

Their weapons of mass destruction

Were inspected and destroyed

The battleships were dismantled

Never again to be deployed

And the world breathed a sigh of relief

After the revolution

Solar panels were on the rooftops

Trains upon the tracks

Organic food was in the markets

No GMO's upon the racks

And all the billionaires

Had to learn how to share

And Bill Gates was told to quit his whining

When he said it wasn't fair

And his mansion became a collective farm

After the revolution

And all the political poets

Couldn't think of what to say

So they all decided

To live life for today

I spent a few years catching up

With all my friends and lovers

Sleeping til eleven

Home beneath the covers

And I learned how to play the accordion

After the revolution

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Ringo Starr

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Free Em All—Mic Crenshaw and David Rovics featuring Opium Sabbah

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

“In His Defense” The People vs. Kevin Cooper

A film by Kenneth A. Carlson

Teaser is now streaming at:

https://www.carlsonfilms.com

Posted by: Death Penalty Focus Blog, January 10, 2022

https://deathpenalty.org/teaser-for-a-kevin-cooper-documentary-is-now-streaming/?eType=EmailBlastContent&eId=1c7299ab-018c-4780-9e9d-54cab2541fa0

“In his Defense,” a documentary on the Kevin Cooper case, is in the works right now, and California filmmaker Kenneth Carlson has released a teaser for it on CarlsonFilms.com

Just over seven months ago, California Gov. Gavin Newsom ordered an independent investigation of Cooper’s death penalty case. At the time, he explained that, “In cases where the government seeks to impose the ultimate punishment of death, I need to be satisfied that all relevant evidence is carefully and fairly examined.”

That investigation is ongoing, with no word from any of the parties involved on its progress.

Cooper has been on death row since 1985 for the murder of four people in San Bernardino County in June 1983. Prosecutors said Cooper, who had escaped from a minimum-security prison and had been hiding out near the scene of the murder, killed Douglas and Peggy Ryen, their 10-year-old daughter, Jessica, and 10-year-old Chris Hughes, a friend who was spending the night at the Ryen’s. The lone survivor of the attack, eight-year-old Josh Ryen, was severely injured but survived.

For over 36 years, Cooper has insisted he is innocent, and there are serious questions about evidence that was missing, tampered with, destroyed, possibly planted, or hidden from the defense. There were multiple murder weapons, raising questions about how one man could use all of them, killing four people and seriously wounding one, in the amount of time the coroner estimated the murders took place.

The teaser alone gives a good overview of the case, and helps explain why so many believe Cooper was wrongfully convicted.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

To: U.S. Senate, U.S. House of Representatives

End Legal Slavery in U.S. Prisons

Sign Petition at:

https://diy.rootsaction.org/petitions/end-legal-slavery-in-u-s-prisons

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Rashid just called with the news that he has been moved back to Virginia. His property is already there, and he will get to claim the most important items tomorrow. He is at a "medium security" level and is in general population. Basically, good news.

He asked me to convey his appreciation to everyone who wrote or called in his support during the time he was in Ohio.

His new address is:

Kevin Rashid Johnson #1007485

Nottoway Correctional Center

2892 Schutt Road

Burkeville, VA 23922

www.rashidmod.com

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Freedom for Major Tillery! End his Life Imprisonment!

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Wrongful Conviction podcast of Kevin Cooper's case, Jason Flom with Kevin and Norm Hile

Please listen and share!

https://omny.fm/shows/wrongful-conviction-podcasts/244-jason-flom-with-kevin-cooper

Kevin Cooper: Important CBS news new report today, and article January 31, 2022

https://apple.news/Akh0syPTGRTO5TgYtwQGDKw

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

Contact: Governor's Press Office

Friday, May 28, 2021

(916) 445-4571

Governor Newsom Announces Clemency Actions, Signs Executive Order for Independent Investigation of Kevin Cooper Case

SACRAMENTO – Governor Gavin Newsom today announced that he has granted 14 pardons, 13 commutations and 8 medical reprieves. In addition, the Governor signed an executive order to launch an independent investigation of death row inmate Kevin Cooper’s case as part of the evaluation of Cooper’s application for clemency.

The investigation will review trial and appellate records in the case, the facts underlying the conviction and all available evidence, including the results of the recently conducted DNA tests previously ordered by the Governor to examine additional evidence in the case using the latest, most scientifically reliable forensic testing.

The text of the Governor’s executive order can be found here:

https://www.gov.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/5.28.21-EO-N-06-21.pdf

The California Constitution gives the Governor the authority to grant executive clemency in the form of a pardon, commutation or reprieve. These clemency grants recognize the applicants’ subsequent efforts in self-development or the existence of a medical exigency. They do not forgive or minimize the harm caused.

The Governor regards clemency as an important part of the criminal justice system that can incentivize accountability and rehabilitation, increase public safety by removing counterproductive barriers to successful reentry, correct unjust results in the legal system and address the health needs of incarcerated people with high medical risks.

A pardon may remove counterproductive barriers to employment and public service, restore civic rights and responsibilities and prevent unjust collateral consequences of conviction, such as deportation and permanent family separation. A pardon does not expunge or erase a conviction.

A commutation modifies a sentence, making an incarcerated person eligible for an earlier release or allowing them to go before the Board of Parole Hearings for a hearing at which Parole Commissioners determine whether the individual is suitable for release.

A reprieve allows individuals classified by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation as high medical risk to serve their sentences in appropriate alternative placements in the community consistent with public health and public safety.

The Governor weighs numerous factors in his review of clemency applications, including an applicant’s self-development and conduct since the offense, whether the grant is consistent with public safety and in the interest of justice, and the impact of a grant on the community, including crime victims and survivors.

While in office, Governor Newsom has granted a total of 86 pardons, 92 commutations and 28 reprieves.

The Governor’s Office encourages victims, survivors, and witnesses to register with CDCR’s Office of Victims and Survivors Rights and Services to receive information about an incarcerated person’s status. For general Information about victim services, to learn about victim-offender dialogues, or to register or update a registration confidentially, please visit:

www.cdcr.ca.gov/Victim_Services/ or call 1-877-256-6877 (toll free).

Copies of the gubernatorial clemency certificates announced today can be found here:

https://www.gov.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/5.28.21-Clemency-certs.pdf

Additional information on executive clemency can be found here:

https://www.gov.ca.gov/clemency/

###

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

New Legal Filing in Mumia’s Case

The following statement was issued January 4, 2022, regarding new legal filings by attorneys for Mumia Abu-Jamal.

Campaign to Bring Mumia Home

In her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, Zora Neale Hurston wrote, “There are years that ask questions, and years that answer.”

With continued pressure from below, 2022 will be the year that forces the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office and the Philly Police Department to answer questions about why they framed imprisoned radio journalist and veteran Black Panther Mumia Abu-Jamal. Abu-Jamal’s attorneys have filed a Pennsylvania Post Conviction Relief Act (PCRA) petition focused entirely on the six boxes of case files that were found in a storage room of the DA’s office in late December 2018, after the case being heard before Judge Leon Tucker in the Court of Common Pleas concluded. (tinyurl.com/zkyva464)

The new evidence contained in the boxes is damning, and we need to expose it. It reveals a pattern of misconduct and abuse of authority by the prosecution, including bribery of the state’s two key witnesses, as well as racist exclusion in jury selection—a violation of the landmark Supreme Court decision Batson v. Kentucky. The remedy for each or any of the claims in the petition is a new trial. The court may order a hearing on factual issues raised in the claims. If so, we won’t know for at least a month.

The new evidence includes a handwritten letter penned by Robert Chobert, the prosecution’s star witness. In it, Chobert demands to be paid money promised him by then-Prosecutor Joseph McGill. Other evidence includes notes written by McGill, prominently tracking the race of potential jurors for the purposes of excluding Black people from the jury, and letters and memoranda which reveal that the DA’s office sought to monitor, direct, and intervene in the outstanding prostitution charges against its other key witness Cynthia White.

Mumia Abu-Jamal was framed and convicted 40 years ago in 1982, during one of the most corrupt and racist periods in Philadelphia’s history—the era of cop-turned-mayor Frank Rizzo. It was a moment when the city’s police department, which worked intimately with the DA’s office, routinely engaged in homicidal violence against Black and Latinx detainees, corruption, bribery and tampering with evidence to obtain convictions.

In 1979, under pressure from civil rights activists, the Department of Justice filed an unprecedented lawsuit against the Philadelphia police department and detailed a culture of racist violence, widespread corruption and intimidation that targeted outspoken people like Mumia. Despite concurrent investigations by the FBI and Pennsylvania’s Attorney General and dozens of police convictions, the power and influence of the country’s largest police association, the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) prevailed.

Now, more than 40 years later, we’re still living with the failure to uproot these abuses. Philadelphia continues to fear the powerful FOP, even though it endorses cruelty, racism, and multiple injustices. A culture of fear permeates the “city of brotherly love.”

The contents of these boxes shine light on decades of white supremacy and rampant lawlessness in U.S. courts and prisons. They also hold enormous promise for Mumia’s freedom and challenge us to choose Love, Not PHEAR. (lovenotphear.com/) Stay tuned.

—Workers World, January 4, 2022

https://www.workers.org/2022/01/60925/

Pa. Supreme Court denies widow’s appeal to remove Philly DA from Abu-Jamal case

Abu Jamal was convicted by a jury of first-degree murder of Faulkner in 1982. Over the past four decades, five of his appeals have been quashed.

In 1989, the state’s highest court affirmed Abu-Jamal’s death penalty conviction, and in 2012, he was re-sentenced to life in prison.

Abu-Jamal, 66, remains in prison. He can appeal to the state Supreme Court, or he can file a new appeal.

KYW Newsradio reached out to Abu-Jamal’s attorneys for comment. They shared this statement in full:

“Today, the Superior Court concluded that it lacked jurisdiction to consider issues raised by Mr. Abu-Jamal in prior appeals. Two years ago, the Court of Common Pleas ordered reconsideration of these appeals finding evidence of an appearance of judicial bias when the appeals were first decided. We are disappointed in the Superior Court’s decision and are considering our next steps.

“While this case was pending in the Superior Court, the Commonwealth revealed, for the first time, previously undisclosed evidence related to Mr. Abu-Jamal’s case. That evidence includes a letter indicating that the Commonwealth promised its principal witness against Mr. Abu-Jamal money in connection with his testimony. In today’s decision, the Superior Court made clear that it was not adjudicating the issues raised by this new evidence. This new evidence is critical to any fair determination of the issues raised in this case, and we look forward to presenting it in court.”

https://www.audacy.com/kywnewsradio/news/local/pennsylvania-superior-court-rejects-mumia-abu-jamal-appeal-ron-castille

Questions and comments may be sent to: info@freedomarchives.org

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Sign our petition urging President Biden to grant clemency to Leonard Peltier.

https://www.freeleonardpeltier.com/petition

Email: contact@whoisleonardpeltier.info

Address: 116 W. Osborne Ave. Tampa, Florida 33603

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

How long will he still be with us? How long will the genocide continue?

By Michael Moore

American Indian Movement leader, Leonard Peltier, at 77 years of age, came down with Covid-19 this weekend. Upon hearing this, I broke down and cried. An innocent man, locked up behind bars for 44 years, Peltier is now America’s longest-held political prisoner. He suffers in prison tonight even though James Reynolds, one of the key federal prosecutors who sent Peltier off to life in prison in 1977, has written to President Biden and confessed to his role in the lies, deceit, racism and fake evidence that together resulted in locking up our country’s most well-known Native American civil rights leader. Just as South Africa imprisoned for more than 27 years its leading voice for freedom, Nelson Mandela, so too have we done the same to a leading voice and freedom fighter for the indigenous people of America. That’s not just me saying this. That’s Amnesty International saying it. They placed him on their political prisoner list years ago and continue to demand his release.

And it’s not just Amnesty leading the way. It’s the Pope who has demanded Leonard Peltier’s release. It’s the Dalai Lama, Jesse Jackson, and the President Pro-Tempore of the US Senate, Sen. Patrick Leahy. Before their deaths, Nelson Mandela, Mother Theresa and Bishop Desmond Tutu pleaded with the United States to free Leonard Peltier. A worldwide movement of millions have seen their demands fall on deaf ears.

And now the calls for Peltier to be granted clemency in DC have grown on Capitol Hill. Senator Brian Schatz (D-HI), the head of the Senate committee who oversees the Bureau of Indian Affairs, has also demanded Peltier be given his freedom. Numerous House Democrats have also written to Biden.

The time has come for our President to act; the same President who appointed the first-ever Native American cabinet member last year and who halted the building of the Keystone pipeline across Native lands. Surely Mr. Biden is capable of an urgent act of compassion for Leonard Peltier — especially considering that the prosecutor who put him away in 1977 now says Peltier is innocent, and that his US Attorney’s office corrupted the evidence to make sure Peltier didn’t get a fair trial. Why is this victim of our judicial system still in prison? And now he is sick with Covid.

For months Peltier has begged to get a Covid booster shot. Prison officials refused. The fact that he now has COVID-19 is a form of torture. A shame hangs over all of us. Should he now die, are we all not complicit in taking his life?

President Biden, let Leonard Peltier go. This is a gross injustice. You can end it. Reach deep into your Catholic faith, read what the Pope has begged you to do, and then do the right thing.

For those of you reading this, will you join me right now in appealing to President Biden to free Leonard Peltier? His health is in deep decline, he is the voice of his people — a people we owe so much to for massacring and imprisoning them for hundreds of years.

The way we do mass incarceration in the US is abominable. And Leonard Peltier is not the only political prisoner we have locked up. We have millions of Black and brown and poor people tonight in prison or on parole and probation — in large part because they are Black and brown and poor. THAT is a political act on our part. Corporate criminals and Trump run free. The damage they have done to so many Americans and people around the world must be dealt with.

This larger issue is one we MUST take on. For today, please join me in contacting the following to show them how many millions of us demand that Leonard Peltier has suffered enough and should be free:

President Joe Biden

Phone: 202-456-1111

E-mail: At this link

https://www.whitehouse.gov/contact/

Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland

Phone: 202-208-3100

E-mail: feedback@ios.doi.gov

Attorney General Merrick Garland

Phone: 202-514-2000

E-mail: At this link

https://www.justice.gov/doj/webform/your-message-department-justice

I’ll end with the final verse from the epic poem “American Names” by Stephen Vincent Benet:

I shall not rest quiet in Montparnasse.

I shall not lie easy at Winchelsea.

You may bury my body in Sussex grass,

You may bury my tongue at Champmedy.

I shall not be there. I shall rise and pass.

Bury my heart at Wounded Knee.

PS. Also — watch the brilliant 1992 documentary by Michael Apted and Robert Redford about the framing of Leonard Peltier— “Incident at Oglala”

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Union Membership—2021

Bureau of Labor Statistics

U.S. Department of Labor

For release 10:00 a.m. (ET) Thursday, January 20, 2022

Technical information:

(202) 691-6378 • cpsinfo@bls.gov • www.bls.gov/cps

Media contact:

(202) 691-5902 • PressOffice@bls.gov

In 2021, the number of wage and salary workers belonging to unions continued to decline (-241,000) to 14.0 million, and the percent who were members of unions—the union membership rate—was 10.3 percent, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. The rate is down from 10.8 percent in 2020—when the rate increased due to a disproportionately large decline in the total number of nonunion workers compared with the decline in the number of union members. The 2021 unionization rate is the same as the 2019 rate of 10.3 percent. In 1983, the first year for which comparable union data are available, the union membership rate was 20.1 percent and there were 17.7 million union workers.

These data on union membership are collected as part of the Current Population Survey (CPS), a monthly sample survey of about 60,000 eligible households that obtains information on employment and unemployment among the nation’s civilian noninstitutional population age 16 and over. For further information, see the Technical Note in this news release.

Highlights from the 2021 data:

• The union membership rate of public-sector workers (33.9 percent) continued to be more than five times higher than the rate of private-sector workers (6.1 percent). (See table 3.)

• The highest unionization rates were among workers in education, training, and library occupations (34.6 percent) and protective service occupations (33.3 percent). (See table 3.)

• Men continued to have a higher union membership rate (10.6 percent) than women (9.9 percent). The gap between union membership rates for men and women has narrowed considerably since 1983 (the earliest year for which comparable data are available), when rates for men and women were 24.7 percent and 14.6 percent, respectively. (See table 1.)

• Black workers remained more likely to be union members than White, Asian, or Hispanic workers. (See table 1.)

• Nonunion workers had median weekly earnings that were 83 percent of earnings for workers who were union members ($975 versus $1,169). (The comparisons of earnings in this news release are on a broad level and do not control for many factors that can be important in explaining earnings differences.) (See table 2.)

• Among states, Hawaii and New York continued to have the highest union membership rates (22.4 percent and 22.2 percent, respectively), while South Carolina and North Carolina continued to have the lowest (1.7 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively). (See table 5.)

Industry and Occupation of Union Members

In 2021, 7.0 million employees in the public sector belonged to unions, the same as in the private sector. (See table 3.)

Union membership decreased by 191,000 over the year in the public sector. The public-sector union membership rate declined by 0.9 percentage point in 2021 to 33.9 percent, following an increase of 1.2 percentage points in 2020. In 2021, the union membership rate continued to be highest in local government (40.2 percent), which employs many workers in heavily unionized occupations, such as police officers, firefighters, and teachers.

The number of union workers employed in the private sector changed little over the year. However, the number of private-sector nonunion workers increased in 2021. The private-sector unionization rate declined by 0.2 percentage point in 2021 to 6.1 percent, slightly lower than its 2019 rate of 6.2 percent. Industries with high unionization rates included utilities (19.7 percent), motion pictures and sound recording industries (17.3 percent), and transportation and warehousing (14.7 percent). Low unionization rates occurred in finance (1.2 percent), professional and technical services (1.2 percent), food services and drinking places (1.2 percent), and insurance (1.5 percent).

Among occupational groups, the highest unionization rates in 2021 were in education, training, and library occupations (34.6 percent) and protective service occupations (33.3 percent). Unionization rates were lowest in food preparation and serving related occupations (3.1 percent); sales and related occupations (3.3 percent); computer and mathematical occupations (3.7 percent); personal care and service occupations (3.9 percent); and farming, fishing, and forestry occupations (4.0 percent).

Selected Characteristics of Union Members

In 2021, the number of men who were union members, at 7.5 million, changed little, while the number of women who were union members declined by 182,000 to 6.5 million. The unionization rate for men decreased by 0.4 percentage point over the year to 10.6 percent. In 2021, women’s union membership rate declined by 0.6 percentage point to 9.9 percent. The 2021 decreases in union membership rates for men and women reflect increases in the total number of nonunion workers. The rate for men is below the 2019 rate (10.8 percent), while the rate for women is above the 2019 rate (9.7 percent). (See table 1.)

Among major race and ethnicity groups, Black workers continued to have a higher union membership rate in 2021 (11.5 percent) than White workers (10.3 percent), Asian workers (7.7 percent), and Hispanic workers (9.0 percent). The union membership rate declined by 0.4 percentage point for White workers, by 0.8 percentage point for Black workers, by 1.2 percentage points for Asian workers, and by 0.8 percentage point for Hispanic workers. The 2021 rates for Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics are little or no different from 2019, while the rate for Asians is lower.

By age, workers ages 45 to 54 had the highest union membership rate in 2021, at 13.1 percent. Younger workers—those ages 16 to 24—had the lowest union membership rate, at 4.2 percent.

In 2021, the union membership rate for full-time workers (11.1 percent) continued to be considerably higher than that for part-time workers (6.1 percent).

Union Representation

In 2021, 15.8 million wage and salary workers were represented by a union, 137,000 less than in 2020. The percentage of workers represented by a union was 11.6 percent, down by 0.5 percentage point from 2020 but the same as in 2019. Workers represented by a union include both union members (14.0 million) and workers who report no union affiliation but whose jobs are covered by a union contract (1.8 million). (See table 1.)

Earnings

Among full-time wage and salary workers, union members had median usual weekly earnings of $1,169 in 2021, while those who were not union members had median weekly earnings of $975. In addition to coverage by a collective bargaining agreement, these earnings differences reflect a variety of influences, including variations in the distributions of union members and nonunion employees by occupation, industry, age, firm size, or geographic region. (See tables 2 and 4.)

Union Membership by State

In 2021, 30 states and the District of Columbia had union membership rates below that of the U.S. average, 10.3 percent, while 20 states had rates above it. All states in both the East South Central and West South Central divisions had union membership rates below the national average, while all states in both the Middle Atlantic and Pacific divisions had rates above it. (See table 5 and chart 1.)

Ten states had union membership rates below 5.0 percent in 2021. South Carolina had the lowest rate (1.7 percent), followed by North Carolina (2.6 percent) and Utah (3.5 percent). Two states had union membership rates over 20.0 percent in 2021: Hawaii (22.4 percent) and New York (22.2 percent).

In 2021, about 30 percent of the 14.0 million union members lived in just two states (California at 2.5 million and New York at 1.7 million). However, these states accounted for about 17 percent of wage and salary employment nationally.

Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic Impact on 2021 Union Members Data

Union membership data for 2021 continue to reflect the impact on the labor market of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Comparisons with union membership measures for 2020, including metrics such as the union membership rate and median usual weekly earnings, should be interpreted with caution. The onset of the pandemic in 2020 led to an increase in the unionization rate due to a disproportionately large decline in the number of nonunion workers compared with the decline in the number of union members. The decrease in the rate in 2021 reflects a large gain in the number of nonunion workers and a decrease in the number of union workers. More information on labor market developments in recent months is available at:

www.bls.gov/covid19/effects-of-covid-19-pandemic-and- response-on-the-employment-situation-news-release.htm.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Resources for Resisting Federal Repression

Since June of 2020, activists have been subjected to an increasingly aggressive crackdown on protests by federal law enforcement. The federal response to the movement for Black Lives has included federal criminal charges for activists, door knocks by federal law enforcement agents, and increased use of federal troops to violently police protests.

The NLG National Office is releasing this resource page for activists who are resisting federal repression. It includes a link to our emergency hotline numbers, as well as our library of Know-Your-Rights materials, our recent federal repression webinar, and a list of some of our recommended resources for activists. We will continue to update this page.

Please visit the NLG Mass Defense Program page for general protest-related legal support hotlines run by NLG chapters.

Emergency Hotlines

If you are contacted by federal law enforcement you should exercise all of your rights. It is always advisable to speak to an attorney before responding to federal authorities.

State and Local Hotlines

If you have been contacted by the FBI or other federal law enforcement, in one of the following areas, you may be able to get help or information from one of these local NLG hotlines for:

- Portland, Oregon: (833) 680-1312

- San Francisco, California: (415) 285-1041 or fbi_hotline@nlgsf.org

- Seattle, Washington: (206) 658-7963

National Hotline

If you are located in an area with no hotline, you can call the following number:

Know Your Rights Materials

The NLG maintains a library of basic Know-Your-Rights guides.

- Know Your Rights During Covid-19

- You Have The Right To Remain Silent: A Know Your Rights Guide for Encounters with Law Enforcement

- Operation Backfire: For Environmental and Animal Rights Activists

WEBINAR: Federal Repression of Activists & Their Lawyers: Legal & Ethical Strategies to Defend Our Movements: presented by NLG-NYC and NLG National Office

We also recommend the following resources:

Center for Constitutional Rights

Civil Liberties Defense Center

- Grand Juries: Slideshow

Grand Jury Resistance Project

Katya Komisaruk

Movement for Black Lives Legal Resources

Tilted Scales Collective

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

By Rod Buntzen, March 27, 2022

Mr. Buntzen is the author of “My Armageddon Experience: A Nuclear Weapons Test Memoir.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/27/opinion/nuclear-weapons-ukraine.html

In the early days of his war against Ukraine, President Vladimir Putin told the world that he had ordered his nation’s nuclear forces to a higher state of readiness. Ever since, pundits, generals and politicians have speculated about what would happen if the Russian military used a nuclear weapon.

What would NATO do? Should the United States respond with its own nuclear weapons?

These speculations all sound hollow to me. Unconvincing words without feeling.

In 1958, as a young scientist for the U.S. Navy, I witnessed the detonation of an 8.9-megaton thermonuclear weapon as it sat on a barge in Eniwetok Atoll, in the Marshall Islands. I watched from across the lagoon at the beach on Parry Island, where my group prepared instrumentation to measure the atmospheric radiation. Sixty-three years later, what I saw remains etched in my mind, which is why I’m so alarmed that the use of nuclear weapons can be discussed so cavalierly in 2022.

Although the potential horror of nuclear weapons remains frozen in films from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the public today has little understanding of the stakes of the Cold War and what might be expected now if the war in Ukraine intentionally or accidentally spins out of control.

The test I witnessed, code-named Oak, was part of a larger series called Hardtack I, which included 35 nuclear detonations over several months in 1958. With world concern about atmospheric testing mounting, the military was eager to test as many different types of weapons as it could before any atmospheric moratorium was announced. The hydrogen bomb used in the Oak test was detonated at 7:30 a.m. A second bomb was set off at noon on nearby Bikini Atoll.

In a nuclear detonation, the thermal and shock effects are the most immediate and are unimaginable. The fission-fusion process that occurs in a thermonuclear explosion happens in a millionth of a second.

As I watched from 20 miles away, all the materials in the bomb, barge and surrounding lagoon water and air, out to a radius of several feet, had been vaporized and raised to a temperature of tens of million degrees.

As the X-rays and neutrons from the bomb raced outward, they left the heavier material particles behind, creating a radiation front that was absorbed by the surrounding air. The radiation, absorption, reradiation and expansion processes continued, cooling the bomb mass within milliseconds.

The outer high-pressure shock region cooled and lost its opacity as it raced toward me, and a hotter inner fireball again appeared.

This point in the process is called breakaway, occurring about three seconds after detonation, when the fireball radius was already nearly 5,500 feet.

By now, the fireball had begun to rise, engulfing more and more atmosphere and sweeping up coral and more lagoon water into an enormous column. The ball of fire eventually reached a radius of 1.65 miles.

Time seemed to have stopped. I had lost my count of the seconds.

The heat was becoming unbearable. Bare spots at my ankles were starting to hurt. The aluminum foil hood I had fashioned for protection was beginning to fail.

I thought that the hair on the back of my head might catch on fire.

The brightness of light the detonation created defies description. I worried that my high-density goggles would fail.

Keeping my eyes closed, I turned until I could see the edge of the fireball.

As I again turned away from the fireball, I opened my eyes inside the goggles and saw outlines of the trees and objects nearby.

The visible light penetrating my goggles increased, and the heat on my back grew more intense. I squirmed to distribute the heat from my side to my back.

About 30 or 40 seconds after detonation, I took off the goggles and watched the angry violet-red and brown cloud from the fireball.

As the rising cloud started to form a mushroom cap, I waited for the shock wave to arrive. In the distance, I could see a long vertical shadow approaching. I instinctively opened my mouth and moved my jaw side to side to equalize pressure difference across my eardrums, closed my eyes and put my hands over my ears.

Pow!

It hit me like a full body slap, knocking me back. I opened my eyes to see another shadow approaching from a slightly different direction. Over the next few seconds, I felt several smaller blows created by reflections of the pressure wave off distant islands.

The fireball kept expanding and climbing at over 200 miles per hour, reaching an altitude of about 2 miles. The boiling mass 20 miles away turned into a mixture of white and gray vapor and continued its climb until it reached somewhere about 100,000 feet.

Meanwhile, the lagoon water had receded like a curtain being pulled back, and the sea bottom slowly appeared. Shark netting that usually protected swimmers lay on the bottom.

Finally, the water stopped receding and appeared to form a wall, like pictures of Moses parting the sea. The wall seemed to remain motionless before finally roaring back.

The water receded for a second time, then repeatedly in smaller and smaller waves and finally as minuscule oscillations across the lagoon surface that lasted all day.

Mankind conducted more than 500 nuclear tests in the atmosphere before moving operations underground, where we tested 1,500 more. Tests to verify the design of weapons. Tests to measure the impact of radiation on people. Tests to make political statements.

During my early Navy career, I focused on scenarios involving nuclear exchanges that could have killed tens of millions of people — what was known during the Cold War as mutually assured destruction.

But the end of the Cold War didn’t bring an end to these fearsome weapons.

Just a few months ago, in January, Russia, China, France, Britain and the United States issued a joint statement affirming that a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.

“We underline our desire to work with all states to create a security environment more conducive to progress on disarmament with the ultimate goal of a world without nuclear weapons with undiminished security for all,” the statement read.

If nuclear weapons are used in Ukraine, the biggest worry is that the conflict could spin quickly out of control. In a strategic war with Russia, hundreds of detonations like the one I witnessed could blanket our countries.

Having witnessed one thermonuclear explosion, I hope that no humans ever have to witness another.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

By Jaeah Lee, March 30, 2022

Ms. Lee is a contributing writer at The New York Times Magazine and a 2021-22 Knight-Wallace reporting fellow.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/30/opinion/rap-music-criminal-trials.html

Tommy Munsdwell Canady was in middle school when he wrote his first rap lyrics. He started out freestyling for friends and family, and after two of his cousins were fatally shot, he found solace in making music. “Before I knew it my pain started influencing all my songs,” he told me in a letter. By his 15th birthday, Mr. Canady was recording and sharing his music online. His tracks had a homemade sound: a pulsing beat mixed with vocals, the words hard to make out through ambient static. That summer, in 2014, Mr. Canady released a song on SoundCloud, “I’m Out Here,” that would change his life.

In Racine, Wis., where Mr. Canady lived, the police had been searching for suspects in three recent shootings. One of the victims, Semar McClain, 19, had been found dead in an alley with a bullet in his temple, his pocket turned out, a cross in one hand and a gold necklace with a pendant of Jesus’ face by his side. The crime scene investigation turned up no fingerprints, weapons or eyewitnesses. Then, in early August, Mr. McClain’s stepfather contacted the police about a song he’d heard on SoundCloud that he believed mentioned Mr. McClain’s name and referred to his murder.

On Aug. 6, 2014, about a week after Mr. Canady released “I’m Out Here,” a SWAT team stormed his home with a “no knock” search warrant. Lennie Farrington, Mr. Canady’s great-grandmother and legal guardian, was up early washing her clothes in the kitchen sink when the police broke through her front door. Mr. Canady was asleep. “They rushed in my room with assault rifles telling me to put my hands up,” he recalled. “I was in the mind state of, This is a big misunderstanding.” He was charged with first-degree intentional homicide and armed robbery.

Prosecutors offered Mr. Canady a plea deal, but he refused, insisting he was innocent. “Honestly, I’m not accepting that,” he told the judge. He decided to go to trial.

I have been reporting on the use of rap lyrics in criminal investigations and trials for more than two years, building a database of cases like Mr. Canady’s in partnership with the University of Georgia and Type Investigations. We have found that over the past three decades, rap — in the form of lyrics, music videos and album images — has been introduced as evidence by prosecutors in hundreds of cases, from homicide to drug possession to gang charges. Rap songs are sometimes used to argue that defendants are guilty even when there’s little other evidence linking them to the crime. What these cases reveal is a serious if lesser-known problem in the courts: how the rules of evidence contribute to racial disparities in the criminal justice system.

Federal and state courts have rules requiring that all evidence — every crime scene photo, DNA sample, witness testimony — be deemed reliable and relevant to the crime at hand before it is shown to a jury. The strength of these rules, however, ultimately rests on the discretion of judges, prosecutors and defense attorneys. Each side makes its case as to how the rules should apply to a particular piece of evidence; the judge makes the final call. Cases like Mr. Canady’s can hinge on interpretation — whether a police officer, prosecutor, judge or jury sees the lyrics as creative expression or proof of a criminal act.

Courts typically treat music and literature as artistic works protected under the First Amendment, even when they contain profane or gruesome material. The small number of non-rap examples that I found — only four since 1950 — involved defendants whose fiction writing or lyrics were considered to be evidence of assault or violent threats. Three of those cases were thrown out; one ended in a conviction that was overturned.

Research has shown that rap is far more likely to be presented in court and interpreted literally than other genres of music. A 2016 study by criminologists at the University of California, Irvine, asked two groups of participants to read the same set of violent lyrics. One group was told the lyrics came from a country song, while the other was told they came from rap. Participants rated whether they found the lyrics offensive and whether they thought the lyrics were fictional or based on the writer’s experience. They judged the lyrics to be more offensive and true to life when told they were rap.

“The findings suggest,” the authors wrote, “that judges might underappreciate the extent to which the label of lyrics — and not the substantive lyrics themselves — impact jurors’ decisions.” Simply describing music as rap, they concluded, is enough to “induce negative evaluations.”

The Irvine findings mirrored those of a study conducted by Stuart Fischoff, a psychology professor at California State University, Los Angeles, almost 20 years earlier. Dr. Fischoff presented 134 students with one of four scenarios about a young man and asked them to rate their impressions of him across nine personality traits, including “caring-uncaring,” “gentle-rough” and “capable of murder-not capable of murder.”

The first scenario described “an 18-year-old African American male high school senior,” a track “champion” with “a good academic record” who made “extra money by singing at local parties.” The second scenario described the same person but added one detail: “He is on trial accused of murdering a former girlfriend who was still in love with him, but has repeatedly declared that he is innocent of the charges.” The third scenario did not mention the murder but instead asked the participant to read a set of rap lyrics by the young man. The fourth mentioned both the murder and the lyrics.

Dr. Fischoff found that the participants who read only about the lyrics reacted more negatively to the young man than the group who had read only about the alleged murder. “Clearly,” he wrote, “participants were more put off by the rap lyrics than by the murder charges.”

At Mr. Canady’s trial in 2016, prosecutors presented evidence that was largely circumstantial. A firearms examiner testified that one of two guns the police found in Ms. Farrington’s apartment, an unloaded .38-caliber revolver, matched the type that the police believed killed Mr. McClain, but conceded there was no way to be certain it was the same gun. Mr. McClain’s cousin testified that he had seen the victim carrying a gun he described as a “black .380,” which prosecutors proposed was similar to the other gun — a loaded pistol — found in Mr. Canady’s home. The government’s theory was that Mr. Canady had killed Mr. McClain and stolen his gun.

But no witness or physical evidence placed Mr. Canady at the crime scene. Mr. McClain’s cousin said that he saw the victim argue with a young man on the day of the murder. He noted that Mr. Canady was one of several people present but not part of the argument. (Mr. Canady told me that he knew Mr. McClain from the neighborhood and that they had friends in common.) A witness who had told the police that he heard Mr. McClain and Mr. Canady discussing guns denied it on the stand.

That’s where the lyrics came in. On the final day of testimony, prosecutors played “I’m Out Here” twice for the jury, first at full speed and then slowed down. A police investigator, Chad Stillman, testified that he heard Mr. Canady say “catch Semar slipping” and other lyrics that he believed alluded to the murder, including references to an alley and bullets hitting a head. Mr. Stillman also read aloud four excerpts from lyrics that Mr. Canady wrote while in jail awaiting trial — a cellmate had turned them over to officers — and interpreted their connections to the crime. “It’s consistently about shooting people,” he said. The lines “blood on my sneaks that’s from his head leaking” and “his last day i took that, im riding around with 2 straps,” Mr. Stillman asserted, referred to Mr. McClain’s head wound and the two guns found in Mr. Canady’s home.

Mr. Canady tried to tell his attorney that the investigators had misheard his song, that an isolated vocal track on his computer would prove he did not name the victim. Where investigators heard “catch Semar slipping,” he said, the actual lyrics were “catch a mawg slippin’,” a slang reference to “someone on the opposite side” and a phrase that he had used in at least one other song.

During cross-examination, the defense attorney pointed out that several of the lyrics Mr. Stillman mentioned did not match the facts of the murder, including the reference to blood on sneakers, “a big Glock with 50 in it,” and an “opp car” — meaning a car belonging to a rival. (The court would later acknowledge that there were, in each of the four exhibits, “other lyrics that do not bear a resemblance to this crime.” One excerpt even ended with a critique of gun violence, in which Mr. Canady condemns all the “killing for no reason” that surrounded him.)

Asked whether he was familiar with rap composition — that boasting and violent imagery are conventions of the genre — Mr. Stillman replied, “Vaguely,” and admitted that he wasn’t sure whether rappers told the truth in their lyrics or not. “I don’t know those artists, you know, what they’ve been through,” he testified. “I know a lot of rappers come from really shady pasts where they’ve committed a large amount of crimes, and they like to brag about those crimes through their lyrics.” (Mr. Stillman, who no longer works for the department, did not reply to a request for an interview.)

Prosecutors relied heavily on the songs in their closing argument. “I think it’s best described as really a tale of two Tommy Canadys,” an assistant district attorney told the jury. “The defendant described it best in his own words,” he added, when Mr. Canady said, “‘I’m handsome and wealthy, with a monster in me.’”

During their deliberation, jurors asked to listen to “I’m Out Here” two more times. After an hour and a half, they found Mr. Canady guilty on both counts. In March 2017, just before his 18th birthday, Mr. Canady was sentenced to life in prison, with the possibility of parole after 50 years.

The rules of evidence are supposed to prohibit the presentation of “character evidence” — information that simply impugns a defendant or reveals past wrongs — to avoid biasing jurors. The use of rap lyrics in Mr. Canady’s case was an example of what legal scholars sometimes call racialized character evidence: details or personal traits prosecutors can use in an insidious way, playing up racial stereotypes to imply guilt. The resulting message, as a Boston University law professor, Jasmine Gonzales Rose, told me, is that the defendant is “that type of Black person.”

“There’s always this bias,” said Andrea Dennis, a University of Georgia law professor who has been studying the use of rap in criminal cases since the early 2000s, “that this young Black man, if they’re rapping, they must only be saying what’s autobiographical and true, because they can’t possibly be creative.” In 2016, Professor Dennis teamed up with Erik Nielson, a University of Richmond professor who studies African American literature, to compile a list of trials in which rap lyrics had been used as evidence. They found roughly 500 defendants, whose cases they discuss in their 2019 book, “Rap on Trial: Race, Lyrics, and Guilt in America.”

I worked with Professor Dennis to track down court documents for more than 200 of those defendants, including their race, how lyrics were used against them and the outcomes of their cases. We found more trials involving rap lyrics in the past decade than during the heyday of the war on crime in the 1990s, which suggests that the practice has become more prevalent despite a broader awareness of racial disparities in the courts and the need for reform. We identified about 50 defendants who were prosecuted using rap between 1990 and 2005, but we found more than double that number in the 15 years that followed.

It’s difficult to pinpoint a single driving force behind this trend. As some scholars have pointed out, the rise of social media, online music platforms and the popularity of rap means that the police and prosecutors have easier access to lyrics and videos. Over the years, courts that have weighed in on the matter of rap evidence have overwhelmingly ruled in favor of admitting and interpreting them literally. Of the cases where court or correctional documents specified the defendant’s race and gender, roughly three-quarters of the defendants were African American men. (Professors Dennis and Nielson note that in some states, such as California, the defendants they identified are predominantly Latino.)

While rap was rarely the only evidence presented in a case, it often played a key role in a prosecutor’s line of argument. Some used snippets of written lyrics or a recording to indicate a confession or articulate a motive. One prosecutor in California argued that lyrics from a notebook found during a search of the defendant’s home showed his intent to murder: Three round bursting real military weaponry / Leaving cold cases for eternity. Others used music videos to show that a defendant had access to a weapon similar to one found at a crime scene or that multiple defendants were in a gang. We found that courts often acknowledged that rap lyrics were prejudicial but still admitted them, concluding that their probative value was greater.

That’s what happened in Mr. Canady’s case. Before his trial, Judge Emily Mueller held a hearing to decide whether to admit several sets of lyrics Mr. Canady wrote while awaiting trial. Judge Mueller acknowledged that introducing rap lyrics to a jury unfamiliar with the genre might cause them to “think this must be some bad guy.” She considered each line in turn. Ambulance come and pick him up aint no face on em / Police come and pick me up aint got shit on me. “It does refer to the face, which I think can refer to a head shot,” she said. “The ambulance coming to pick up the person, and then police coming to pick up the writer. ‘Aint got shit on me,’ which I assume means they don’t have any evidence.” She decided to allow the lyrics because they constituted a sufficient “nexus” to the crime — an idea that’s appeared in numerous rap cases and has been criticized by some for being a meaningless standard. “While I am cognizant of the prejudice,” Judge Mueller concluded, “I don’t believe that it is undue prejudice here.” (Judge Mueller declined a request for an interview.)

Deborah Gonzalez, the district attorney who covers Athens-Clarke County in Georgia, said rap lyrics present a conundrum for prosecutors whose job is to prove guilt. She cautions those in her office against relying on rap lyrics without context or other convincing evidence, but she also sees how they could be valuable. “We’re in this Catch-22,” she said, describing trying to decide whether something was a threat or creative expression. “That’s where it sometimes gets a little iffy out there, when you can’t say that it’s 100 percent one or the other.”

Prosecutors also used rap to justify harsher sentences. In sentencing hearings, information that is off-limits during a trial, like character evidence or prior crimes, is fair game. Of the cases we reviewed, a majority of defendants went on to serve sentences of 10 years or longer; roughly a quarter received life sentences, and at least 17 people received death sentences, including Nathaniel Woods, a Black man in Alabama who was convicted of serving as an accomplice to the murder of three police officers. Mr. Woods maintained his innocence; another man, Kerry Spencer, confessed to the murder and was convicted in a separate trial. When Mr. Woods appealed his verdict, however, prosecutors countered by presenting evidence that included lyrics he was alleged to have written while in jail awaiting trial: Seven execution-style murders / I have no remorse because I’m the fucking murderer. / Haven’t you ever heard of a killa / I drop pigs like Kerry Spencer. Mr. Woods was executed in 2020. He had adapted the lyrics from a Dr. Dre song.

Evidence rules not only fail to curtail racial bias in the courts; they also enable it to thrive in plain sight. That’s why a growing number of scholars, lawyers and legislators are calling for rethinking the rules themselves. Take Federal Rule 403, which gives judges the power to exclude relevant evidence if it has a much higher risk of creating unfair prejudice or confusion, or misleading a jury. What if that rule required judges to first assess whether the burden of proof could be met without evidence like rap lyrics? Prosecutors are already asking this question in Athens-Clarke County, Ga., where Ms. Gonzalez, the district attorney, has studied Professors Dennis and Nielson’s work.

Or what if the rules simply barred rap lyrics in the first place? That’s what two New York state senators, Brad Hoylman and Jamaal Bailey, hope to achieve in a bill they introduced last fall. If passed, it would be the first to prohibit prosecutors from using rap lyrics or other creative expression as criminal evidence “without clear and convincing proof that there is a literal, factual nexus.” The bill, which has garnered support from musicians including Jay-Z, Meek Mill and Kelly Rowland, was approved in committee in January and awaits a full vote.

In 2019, two years into his sentence at the Columbia Correctional Institution in Portage, Wis., Mr. Canady asked the court to grant him a new trial. His lawyer, Jefren Olsen, argued in a brief that Mr. Canady’s trial attorney had demonstrated ineffective counsel by failing to obtain the original recordings of “I’m Out Here” and that the judge should not have admitted the written rap lyrics in the first place.

“The parties argued a great deal” about “whether Canady’s lyrics as a whole constitute posturing and braggadocio or a representation of who he is and what he does,” Mr. Olsen wrote. The overall effect was to convince the jury of “Canady’s general bad character” without necessarily proving “his specific conduct in this case.” In July 2020, Mr. Canady finally obtained the original song mix and the isolated vocal track that he believed would give him the chance to prove his innocence.

Getting a new trial, however, requires clearing a high bar. Defendants must typically prove that the original lawyers or judge committed a serious error, and they must make a convincing case that without the error, the jury would have been likely to reach a different verdict. Arguments having to do with the interpretation of evidence do not often meet that threshold. Only Mr. Canady knows whether he is innocent. But the rest of us must ask ourselves what we’re asking jurors to judge, what we’re ultimately putting on trial, when the evidence is rap.

In May 2021, the judge who presided over Mr. Canady’s trial denied his request for a new one. (In Wisconsin, the circuit court oversees both the trial phase and the first appeal following a conviction.) Mr. Canady has since challenged the decision in the Wisconsin Court of Appeals. In a new brief, his attorney, Mr. Olsen, argues for a stricter relevance standard to be applied when the evidence in question is rap lyrics. If the appeal is successful, it could set a new precedent in the state.

Meanwhile, Mr. Canady continues to write in prison. “Music is the only way I know how to vent,” he told me. “I pour my heart out, and let my soul do the singing.”

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

By Charles M. Blow, March 30, 2022

On a warm August night in 1955 on the outskirts of Money, Miss., about a hundred miles due north of Jackson, two men arrived with a flashlight and a gun at the house where Emmett Till was staying with his aunt and uncle.

Till was just 14 years old. He was visiting from Chicago. He had been accused of whistling at, flirting with or touching a white woman.

It was 2 o’clock on a Sunday morning. The men barged into the house, entered the room where Till slept, shined the flashlight in his face and asked, “You the niggah that did the talking down at Money?”

They forced the boy to get dressed, put him in a car and rode off with him, this over the pleadings of his uncle and aunt. One of the men asked the uncle how old he was. “Sixty-four,” the uncle answered. “Well,” the man responded, “if you know any of us here tonight, then you will never live to get to be 65.”

After hours of driving and just before daybreak, the men took Till to a tool shed and began to pistol-whip him. But, as one of the men would tell Look magazine the next year, Till was still defiant, yelling at one point: “You bastards, I’m not afraid of you. I’m as good as you are. I’ve ‘had’ white women. My grandmother was a white woman.”

(It is important to remember that these men are killers, and their word is suspect. The confession, and what it projects onto the Black boy they killed, must be viewed with caution and in context.)

The man told the magazine that he liked Black people (he used a slur, of course), as long as they were “in their place.” And as long as he lived and could, he said, he was going to keep them in their place. So when he heard Till “throw that poison at me” about white women, “I just made up my mind. ‘Chicago boy,’ I said, ‘I’m tired of ’em sending your kind down here to stir up trouble. Goddam you, I’m going to make an example of you — just so everybody can know how me and my folks stand.’”

They forced the boy back in the car and drove him to a cotton ginning factory in another town. The sun had risen by the time they arrived. They stole the fan of a cotton gin, loaded it in the car and drove away.

They parked at a spot near the Tallahatchie River. They forced the boy to remove the heavy cotton gin fan from the car and to strip naked. They then shot him in the right side of his face, near his ear.

The boy dropped to the ground. The men tied his body with barbed wire to the cotton gin fan and pushed it into the river.

Three days later, Till’s body — bloated and disfigured — was fished out of the river several miles downstream.

Local authorities sent the boy’s body back to his mother, Mamie Till, in Chicago in a coffin that was nailed shut. She demanded that it be opened. The body reeked because it had already started to decompose. As his mother later recounted viewing the body for the first time:

“I saw that his tongue was choked out. I noticed that the right eye was lying on midway his cheek, I noticed that his nose had been broken like somebody took a meat chopper and chopped his nose in several places. As I kept looking, I saw a hole, which I presumed was a bullet hole and I could look through that hole and see daylight on the other side.”

Emmett Till had been lynched, without question, but there had been no mob that did the deed and there had been no hanging. There was a beating and shooting and heinous disposal of the body.

Both men were acquitted of murder, by the way.

Lynching was never only about hanging. It was about a motive and means of injury and death, and lynchings have always needed specific legislation to make them punishable. Finally, on Tuesday, after 100 years of failed efforts on the part of liberal legislators to get such provisions written into law, President Biden signed the Emmett Till Anti-lynching Act, which makes lynching a federal hate crime punishable by up to 30 years in prison.

The wording of the bill doesn’t specify hanging, but instead defines a lynching as a hate crime that results in death or serious bodily injury.

Still, some Americans continue to demonstrate a fundamental ignorance about lynching. Take Fox News’s Jesse Watters, who asked why a hate crimes bill is a priority now, saying, “nobody has been lynched in America in decades.” This is patently false.

Ahmaud Arbery was lynched in 2020 when two men, joined by a third, chased him down while he was jogging, killed him in the street in broad daylight and stood over his body, not rendering aid, as he bled out.

You could also argue that George Floyd was lynched, a few months later, when officers held him down and Officer Derek Chauvin pressed the life out of him on a public street. In fact, I think that you could make a strong case that several high-profile police killings were in fact lynchings.

And who would debate that James Byrd Jr. was lynched in 1998 when three white men took him to the woods, beat him, urinated on him, tied his ankles to the back of their truck and dragged his body for three miles, the pavement sanding away at his flesh. An autopsy found that he most likely died only when he was decapitated by a culvert about halfway through the dragging.

I, too, wish that lynching was only an ugly feature of America’s past, but sadly that simply isn’t the case. Lynching is still a thing.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*--------*

—Common Dreams, April 1, 2022

https://www.commondreams.org/news/2022/04/01/workers-new-york-vote-form-amazons-first-ever-union-us

Amazon Labor Union members gather at a watch event as union election votes are counted in Brooklyn, New York on March 31, 2022. (Photo: Ed Jones/AFP via Getty Images)

Amazon workers in Staten Island, New York won their election Friday, April 1, 2022, to form the retail giant’s first-ever union in the United States, a landmark victory for the labor movement in the face of aggressive union-busting efforts from one of the world’s most powerful companies.

CNBC reported that “while the official vote tally hasn’t been announced, the union’s lead is large enough that remaining and contested ballots are unlikely to sway the outcome of the election.”

“The latest tally, according to a union organizer, is 2,350 in favor of joining and 1,912 opposed,” the outlet noted.

Bloomberg also reported the union’s victory.

“In my 25 years writing about labor, the unionization victory at the Amazon warehouse in Staten Island is by far the biggest, beating-the-odds David-versus-Goliath unionization win I’ve seen,” veteran reporter Steven Greenhouse wrote on Twitter as the vote count was completed.

The unionization drive was led by Amazon Labor Union (ALU), a worker-led group not affiliated with any established union. Christian Smalls, the president of ALU, was fired by Amazon in 2020 after he led a protest against the company’s poor workplace safety standards in the early stages of the coronavirus pandemic.

“A fired Amazon worker took on Amazon’s union busters and unionized a 5,000-worker warehouse,” Greenhouse wrote.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

By Binyamin Applebaum, April 1, 2022

Andrea Renault/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

Two years ago, Amazon fired Christian Smalls after he organized fellow workers at a warehouse on Staten Island to protest pandemic working conditions. On Friday, after a campaign the company bitterly opposed, the government announced that those workers had voted to unionize, and Mr. Smalls, their leader, popped open a bottle of champagne.

It was a heady moment for the union movement in the United States, a high-profile victory that follows recent votes to organize workers at several Starbucks.

“Do you see what’s happening out there?” the A.F.L.-C.I.O.’s president, Elizabeth Shuler, asked the crowd this week at a labor convention in Pittsburgh. “Working people are rising up.”

But it is a false dawn. The number of American workers who are represented by unions drops with almost every passing year. It reached a new low last year. And it will not recover unless and until the federal government changes the rules of the game.

The new Amazon Labor Union — the first union for U.S. workers at Amazon, one of the nation’s largest employers — is remarkable, and worthy of celebration, precisely because it is so very difficult to unionize. Both federal protections and the enforcement of those protections are grossly inadequate.

President Biden has been more outspoken in his support for organized labor than any of his predecessors in the White House, but that is actually a sign of the weakness of the union movement, which no longer has the power to make a Democratic president uncomfortable.

The decline of unions is often narrated as a straightforward consequence of the decline of industrial employment. Fewer steelworkers, fewer United Steelworkers.

Another standard talking point is that the government supplanted unions as the primary protector of workers’ interests during the mid-20th century, writing into law many of the movement’s original goals, like putting a floor on wages and a ceiling on hours worked.

But federal oversight is an imperfect substitute for ensuring that workers can define and defend their own collective interests. Just this week, three Senate Democrats blocked the confirmation of David Weil to lead the Labor Department’s wage and hour division, which is supposed to protect workers. Mr. Weil held the same job under President Barack Obama and earned a reputation for trying to do it — for example, by seeking to prevent companies from improperly treating workers as contractors. Employers did not want an encore.

“I heard from a lot of business owners,” Senator Mark Kelly of Arizona, one of the three Democrats, told Politico by way of justification for his opposition.

Tellingly, the share of workers who would like to be in unions is much higher than the share of unionized workers. The government has cooperated with employers to frustrate that desire. Almost as soon as it had legalized collective bargaining in the 1930s, Congress began to backtrack, constraining American unions more tightly than unions in other democracies.

The government has gradually granted employers wide-ranging powers to frustrate unionization campaigns through propaganda, via threatened and actual mistreatment of workers and by closing operations if workers vote to unionize. To the extent that some tactics remain illegal, companies rarely suffer anything more than token penalties.

The House passed legislation last year, backed by Mr. Biden, that would address some of these abuses, but it died in the Senate. Bolder reforms, such as allowing workers in a given industry to negotiate wages and salaries collectively, rather than requiring individual contracts in each workplace, remain the stuff of campaign speeches.

The workers at JFK8, that Amazon warehouse on Staten Island, overcame the obstacles.

The campaign was fueled by anger about working conditions and a sense that they were not reaping a fair share of Amazon’s success. It also was personal. After Mr. Smalls was fired for raising concerns about workers’ safety during the early months of the Covid pandemic, a top Amazon executive described him as “not smart or articulate.” Some of his former colleagues figured that was roughly how the company felt about them, too.

During the unionization campaign, Amazon insisted that the police arrest Mr. Smalls and two current workers who brought food to the warehouse. Before the vote, the union projected the words “They arrested your co-workers” on one of the outside walls.

The circumstances were extraordinary, which is what it takes to win under the current rules. A parallel organizing campaign at an Amazon warehouse in Alabama mounted by the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union appears headed for defeat.

The victory is still incomplete. The vote establishes the union as the official representative of the JFK8 workers. But companies often refuse to negotiate. An analysis of union votes in 2007 found that among the roughly 900 groups of workers who voted to engage in collective bargaining, fewer than half obtained a first contract within the following year. Three years later, almost a third still had not obtained that first contract.

Amazon said Friday that it might seek to have the vote thrown out. “We believe having a direct relationship with the company is best for our employees,” it said. Its employees have reached a different conclusion, and not out of ignorance of the company’s case. They were required to sit through meetings where they were told what was good for them.

Union leaders have responded to the victory by announcing plans to press for votes at other Amazon warehouses. Mr. Smalls’s union has already secured a vote at another warehouse on Staten Island this month. As in the early 20th century, the union movement may well have no option but to win on a tilted field in order to have a fair chance.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

The strike at an Alabama coal mine is one of the longest in U.S. history. To make ends meet, some striking miners have picked up work at an Amazon warehouse. It’s the same warehouse where workers are trying to unionize.

By Michael Corkery, April 2, 2022

BROOKWOOD, Ala. — Braxton Wright is a second-generation coal miner, a die-hard union supporter and, until recently, a staunch Republican. He is named after his uncle, a Korean War veteran, who was fatally crushed between two rail cars while working at the Pullman train factory near Birmingham.

Hard dangerous work is a part of Mr. Wright’s extended family history and that of many people living in this industrial and mining belt of north central Alabama. Next to the coal mine where Mr. Wright works, there is a memorial to the miners who were killed in an underground explosion in September 2001. Every year, on the disaster’s anniversary, a bell tolls once for each of the 13 workers who died.

In agreeing to these dangers, Mr. Wright, 39, says he and his fellow coal miners have come to expect something in return from their employer — respect.

After accepting pay cuts when the coal company emerged from a 2015 bankruptcy, the miners said they expected that their previous wages would be restored to match what other mines paid. The company, Warrior Met Coal, declined to comment for this article. It says on its website that Warrior Met made no such promise and has provided multiple raises in recent years.

On April 1, 2021, Mr. Wright joined about 900 other miners who walked off the job and set up picket lines around the mine’s entrances, demanding that the company raise their wages close to the levels they received before the bankruptcy.

Less than 30 miles away from where the mine sits is the Amazon warehouse in Bessemer, Ala., a building that encompasses 14 football fields and employs more than 6,000 people. The workers there have recently voted for a second time on whether to form a union.

A previous election last spring ended in a defeat for the union by a wide margin. The most recent results now hinge on a series of disputed ballots that will be reviewed in the coming weeks, but the contest is closer than many anticipated. On Friday, organized labor scored a surprising victory as workers at an Amazon facility on Staten Island voted to unionize.

It is a stark tableau of the American economy: coal miners dug into a contract dispute in a diminished industry and low-wage workers seeking more leverage at a high-tech company whose growth seems limitless.

Forming a union is a significant step, but maintaining a strike for 365 days requires a measure of solidarity that seems difficult to muster in a deeply divided society. The miners are a mix of Trump supporters and Biden voters, Black workers from Birmingham and white workers from rural towns near the mine. They have supported one another with food donations and camaraderie during a year on the picket line.