International Webinar — February 1, 2022

Register: https://bit.ly/iwa-2022

1:00pm SF, 4:00pm NYC, 6:00pm Rio de Janeiro, 9:00pm London, 11:00pm Johannesburg, 6:00am Tokyo

Recent Organizational Endorsers Include:

Alameda Labor Council, UNITE (UK), Alameda County Council Green Party, Democracia Socialista de Puerto Rico, National Alumni Association of the Black Panther Party, Oscar Grant Committee against Police Brutality and State Repression, San Francisco Bay Area IWW General Membership Branch

https://www.facebook.com/IWAFAPP/

InternationalWorkersAction@gmail.com

Endorse: https://forms.gle/ijBocFw5zBx6AP28A

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Register here:

https://www.eventbrite.com/e/viva-la-educacion-supporting-education-resisting-the-blockade-tickets-251164318237?aff=odeccpebemailcampaigns&utm_source=eventbrite&utm_medium=ebcampaigns&utm_campaign=2214769&utm_term=ctabutton&mipa=ABIdvVuQ5rOO0VL1BnSKpc8iKj3aHbZP2WeYnn6MK7A_rLh1sZsElEfuphMl9rpTAwuFi0qARX028-Mw9ihkpQEaEyfQwpMpBaoDQHUQxoVnvch_oIkXoJOlbtNM7FgB8nww7aa6uEKpzdQXCNcg7hephVHc04NYSupcpMhH41nmMzPq8yRmPLoJRcKC_xznQoND_eAF0DolS_V9a6E7Hv5PRJ6f7hxuGRIMaw3wSKLEpr7Gzj5pflBnI4pFPKQP8HtmpEvP-aFh2jYJ_V8-rh4i1TeBwHmAvw#tickets

Viva La Educación – educational appeal launch

Dear Friend,

Join us on Tuesday 1 February for the online launch of a major new appeal to raise money for essential classroom and teaching equipment to be shipped to Cuban schools.

‘Viva La Educación’ – is a joint appeal by the National Education Union(NEU) and the Cuba Solidarity Campaign(CSC) Music Fund for Cuba, and Cuba’s education union (SNTECD). Cuba has some of the best education indicators in Latin America. Its achievements in literacy and further education compare well with others in the region. However Cuban students and teachers often have to make do without many of the basic necessities that we take for granted.

Join us on Tuesday to find out how you can get involved in 'Viva La Educación' and support students and teachers in Cuba.

with guest speakers

· Daniel Kebede, President NEU;

· Isora Enriquez O’Frarrill, Cuban teacher;

· Rob Miller, Director CSC;

· Dawn Taylor, Vice Chair International Committee, NEU;

· Members of NEU Cuba delegations 2015-2019

Yours in solidarity,

Cuba Solidarity Campaign Team

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

US/NATO Aggression at the Russian Border

A conversation between US, Russian and Ukrainian Peace activists

Webinar, Sunday, February 6,

12 noon Eastern (US/Canada)

Click here to register:

https://us06web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_984zj4TsQ8er6Ja5z3F9vg

Speakers will include:

Ajamu Baraka, National Organizer, Black Alliance for Peace

Larissa Shessler, Chair, Union of Political Emigrants & Political prisoners of Ukraine

Bruce Gagnon, Coordinator, Global Network Against Weapons & Nuclear Power in Space

Joe Lombardo, Coordinator, United National Antiwar Coalition (UNAC)

Vladimir Kozin, Correspondent member, Russian Academy of Science

Leonid Ilderkin, Coordinating Council of the Union of Political Emigrants and Political Prisoners of Ukraine.

Corporate media in the US has been warning about a possible invasion of Ukraine by Russia. This, Russia denies. But this propaganda has been used by the Biden Administration to whip up sentiment for war. Billions of dollars of US arms have been sent to Ukraine, Ukraine has massed an estimated 145,000 troops on the Russian border with US “advisors” supporting their effort. For years the US and its Western allies have moved NATO into Eastern European and former Soviet States in violation of agreements made with Russia. They have installed missiles at the Russian border and conducted “war games” at the Russian border. Today’s threat is a threat against a major nuclear power that puts the entire world in danger. Join us for this important webinar with voices for peace from Russia, Ukraine and the US.

Click here for UNAC's statement on the situation on the Russian border: https://nepajac.org/USrussia.htm

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

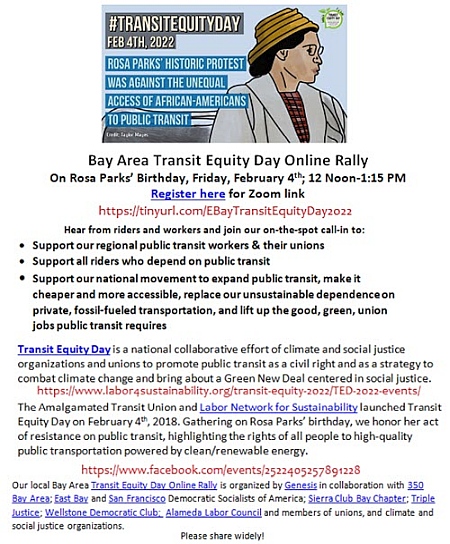

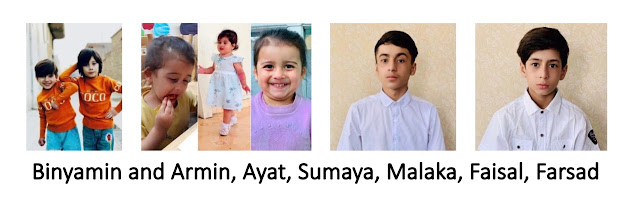

The Ahmadi Family Drone Massacre, August 29, 2021…..We will not forget

United in Action to STOP KILLER DRONES:

SHUT DOWN CREECH!

Spring Action, 2022

March 26 - April 2—Saturday to Saturday

Co-sponsored by CODEPINK and Veterans For Peace

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Screenshot of Kevin Cooper's artwork from the teaser. “In His Defense” The People vs. Kevin Cooper

A film by Kenneth A. Carlson

Teaser is now streaming at:

https://www.carlsonfilms.com

Posted by: Death Penalty Focus Blog, January 10, 2022

https://deathpenalty.org/teaser-for-a-kevin-cooper-documentary-is-now-streaming/?eType=EmailBlastContent&eId=1c7299ab-018c-4780-9e9d-54cab2541fa0

“In his Defense,” a documentary on the Kevin Cooper case, is in the works right now, and California filmmaker Kenneth Carlson has released a teaser for it on CarlsonFilms.com

Just over seven months ago, California Gov. Gavin Newsom ordered an independent investigation of Cooper’s death penalty case. At the time, he explained that, “In cases where the government seeks to impose the ultimate punishment of death, I need to be satisfied that all relevant evidence is carefully and fairly examined.”

That investigation is ongoing, with no word from any of the parties involved on its progress.

Cooper has been on death row since 1985 for the murder of four people in San Bernardino County in June 1983. Prosecutors said Cooper, who had escaped from a minimum-security prison and had been hiding out near the scene of the murder, killed Douglas and Peggy Ryen, their 10-year-old daughter, Jessica, and 10-year-old Chris Hughes, a friend who was spending the night at the Ryen’s. The lone survivor of the attack, eight-year-old Josh Ryen, was severely injured but survived.

For over 36 years, Cooper has insisted he is innocent, and there are serious questions about evidence that was missing, tampered with, destroyed, possibly planted, or hidden from the defense. There were multiple murder weapons, raising questions about how one man could use all of them, killing four people and seriously wounding one, in the amount of time the coroner estimated the murders took place.

The teaser alone gives a good overview of the case, and helps explain why so many believe Cooper was wrongfully convicted.

To: U.S. Senate, U.S. House of Representatives

End Legal Slavery in U.S. Prisons

Sign Petition at:

https://diy.rootsaction.org/petitions/end-legal-slavery-in-u-s-prisons

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

On the anniversary of the 26th of July Movement’s founding, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research launches the online exhibition, Let Cuba Live. 80 artists from 19 countries – including notable cartoonists and designers from Cuba – submitted over 100 works in defense of the Cuban Revolution. Together, the exhibition is a visual call for the end to the decades-long US-imposed blockade, whose effects have only deepened during the pandemic. The intentional blocking of remittances and Cuba’s use of global financial institutions have prevented essential food and medicine from entering the country. Together, the images in this exhibition demand: #UnblockCuba #LetCubaLive

Please contact art@thetricontinental.org if you are interested in organising a local exhibition of the exhibition.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Rashid just called with the news that he has been moved back to Virginia. His property is already there, and he will get to claim the most important items tomorrow. He is at a "medium security" level and is in general population. Basically, good news.

He asked me to convey his appreciation to everyone who wrote or called in his support during the time he was in Ohio.

His new address is:

Kevin Rashid Johnson #1007485

Nottoway Correctional Center

2892 Schutt Road

Burkeville, VA 23922

www.rashidmod.com

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Freedom for Major Tillery! End his Life Imprisonment!

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

Contact: Governor's Press Office

Friday, May 28, 2021

(916) 445-4571

Governor Newsom Announces Clemency Actions, Signs Executive Order for Independent Investigation of Kevin Cooper Case

SACRAMENTO – Governor Gavin Newsom today announced that he has granted 14 pardons, 13 commutations and 8 medical reprieves. In addition, the Governor signed an executive order to launch an independent investigation of death row inmate Kevin Cooper’s case as part of the evaluation of Cooper’s application for clemency.

The investigation will review trial and appellate records in the case, the facts underlying the conviction and all available evidence, including the results of the recently conducted DNA tests previously ordered by the Governor to examine additional evidence in the case using the latest, most scientifically reliable forensic testing.

The text of the Governor’s executive order can be found here:

https://www.gov.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/5.28.21-EO-N-06-21.pdf

The California Constitution gives the Governor the authority to grant executive clemency in the form of a pardon, commutation or reprieve. These clemency grants recognize the applicants’ subsequent efforts in self-development or the existence of a medical exigency. They do not forgive or minimize the harm caused.

The Governor regards clemency as an important part of the criminal justice system that can incentivize accountability and rehabilitation, increase public safety by removing counterproductive barriers to successful reentry, correct unjust results in the legal system and address the health needs of incarcerated people with high medical risks.

A pardon may remove counterproductive barriers to employment and public service, restore civic rights and responsibilities and prevent unjust collateral consequences of conviction, such as deportation and permanent family separation. A pardon does not expunge or erase a conviction.

A commutation modifies a sentence, making an incarcerated person eligible for an earlier release or allowing them to go before the Board of Parole Hearings for a hearing at which Parole Commissioners determine whether the individual is suitable for release.

A reprieve allows individuals classified by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation as high medical risk to serve their sentences in appropriate alternative placements in the community consistent with public health and public safety.

The Governor weighs numerous factors in his review of clemency applications, including an applicant’s self-development and conduct since the offense, whether the grant is consistent with public safety and in the interest of justice, and the impact of a grant on the community, including crime victims and survivors.

While in office, Governor Newsom has granted a total of 86 pardons, 92 commutations and 28 reprieves.

The Governor’s Office encourages victims, survivors, and witnesses to register with CDCR’s Office of Victims and Survivors Rights and Services to receive information about an incarcerated person’s status. For general Information about victim services, to learn about victim-offender dialogues, or to register or update a registration confidentially, please visit:

www.cdcr.ca.gov/Victim_Services/ or call 1-877-256-6877 (toll free).

Copies of the gubernatorial clemency certificates announced today can be found here:

https://www.gov.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/5.28.21-Clemency-certs.pdf

Additional information on executive clemency can be found here:

https://www.gov.ca.gov/clemency/

###

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

New Legal Filing in Mumia’s Case

The following statement was issued January 4, 2022, regarding new legal filings by attorneys for Mumia Abu-Jamal.

Campaign to Bring Mumia Home

In her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, Zora Neale Hurston wrote, “There are years that ask questions, and years that answer.”

With continued pressure from below, 2022 will be the year that forces the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office and the Philly Police Department to answer questions about why they framed imprisoned radio journalist and veteran Black Panther Mumia Abu-Jamal. Abu-Jamal’s attorneys have filed a Pennsylvania Post Conviction Relief Act (PCRA) petition focused entirely on the six boxes of case files that were found in a storage room of the DA’s office in late December 2018, after the case being heard before Judge Leon Tucker in the Court of Common Pleas concluded. (tinyurl.com/zkyva464)

The new evidence contained in the boxes is damning, and we need to expose it. It reveals a pattern of misconduct and abuse of authority by the prosecution, including bribery of the state’s two key witnesses, as well as racist exclusion in jury selection—a violation of the landmark Supreme Court decision Batson v. Kentucky. The remedy for each or any of the claims in the petition is a new trial. The court may order a hearing on factual issues raised in the claims. If so, we won’t know for at least a month.

The new evidence includes a handwritten letter penned by Robert Chobert, the prosecution’s star witness. In it, Chobert demands to be paid money promised him by then-Prosecutor Joseph McGill. Other evidence includes notes written by McGill, prominently tracking the race of potential jurors for the purposes of excluding Black people from the jury, and letters and memoranda which reveal that the DA’s office sought to monitor, direct, and intervene in the outstanding prostitution charges against its other key witness Cynthia White.

Mumia Abu-Jamal was framed and convicted 40 years ago in 1982, during one of the most corrupt and racist periods in Philadelphia’s history—the era of cop-turned-mayor Frank Rizzo. It was a moment when the city’s police department, which worked intimately with the DA’s office, routinely engaged in homicidal violence against Black and Latinx detainees, corruption, bribery and tampering with evidence to obtain convictions.

In 1979, under pressure from civil rights activists, the Department of Justice filed an unprecedented lawsuit against the Philadelphia police department and detailed a culture of racist violence, widespread corruption and intimidation that targeted outspoken people like Mumia. Despite concurrent investigations by the FBI and Pennsylvania’s Attorney General and dozens of police convictions, the power and influence of the country’s largest police association, the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) prevailed.

Now, more than 40 years later, we’re still living with the failure to uproot these abuses. Philadelphia continues to fear the powerful FOP, even though it endorses cruelty, racism, and multiple injustices. A culture of fear permeates the “city of brotherly love.”

The contents of these boxes shine light on decades of white supremacy and rampant lawlessness in U.S. courts and prisons. They also hold enormous promise for Mumia’s freedom and challenge us to choose Love, Not PHEAR. (lovenotphear.com/) Stay tuned.

—Workers World, January 4, 2022

https://www.workers.org/2022/01/60925/

Pa. Supreme Court denies widow’s appeal to remove Philly DA from Abu-Jamal case

Abu Jamal was convicted by a jury of first-degree murder of Faulkner in 1982. Over the past four decades, five of his appeals have been quashed.

In 1989, the state’s highest court affirmed Abu-Jamal’s death penalty conviction, and in 2012, he was re-sentenced to life in prison.

Abu-Jamal, 66, remains in prison. He can appeal to the state Supreme Court, or he can file a new appeal.

KYW Newsradio reached out to Abu-Jamal’s attorneys for comment. They shared this statement in full:

“Today, the Superior Court concluded that it lacked jurisdiction to consider issues raised by Mr. Abu-Jamal in prior appeals. Two years ago, the Court of Common Pleas ordered reconsideration of these appeals finding evidence of an appearance of judicial bias when the appeals were first decided. We are disappointed in the Superior Court’s decision and are considering our next steps.

“While this case was pending in the Superior Court, the Commonwealth revealed, for the first time, previously undisclosed evidence related to Mr. Abu-Jamal’s case. That evidence includes a letter indicating that the Commonwealth promised its principal witness against Mr. Abu-Jamal money in connection with his testimony. In today’s decision, the Superior Court made clear that it was not adjudicating the issues raised by this new evidence. This new evidence is critical to any fair determination of the issues raised in this case, and we look forward to presenting it in court.”

https://www.audacy.com/kywnewsradio/news/local/pennsylvania-superior-court-rejects-mumia-abu-jamal-appeal-ron-castille

Questions and comments may be sent to: info@freedomarchives.org

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Sign our petition urging President Biden to grant clemency to Leonard Peltier.

https://www.freeleonardpeltier.com/petition

Thank you!

Email: contact@whoisleonardpeltier.info

Address: 116 W. Osborne Ave. Tampa, Florida 33603

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Resources for Resisting Federal Repression

Since June of 2020, activists have been subjected to an increasingly aggressive crackdown on protests by federal law enforcement. The federal response to the movement for Black Lives has included federal criminal charges for activists, door knocks by federal law enforcement agents, and increased use of federal troops to violently police protests.

The NLG National Office is releasing this resource page for activists who are resisting federal repression. It includes a link to our emergency hotline numbers, as well as our library of Know-Your-Rights materials, our recent federal repression webinar, and a list of some of our recommended resources for activists. We will continue to update this page.

Please visit the NLG Mass Defense Program page for general protest-related legal support hotlines run by NLG chapters.

Emergency Hotlines

If you are contacted by federal law enforcement you should exercise all of your rights. It is always advisable to speak to an attorney before responding to federal authorities.

State and Local Hotlines

If you have been contacted by the FBI or other federal law enforcement, in one of the following areas, you may be able to get help or information from one of these local NLG hotlines for:

- Portland, Oregon: (833) 680-1312

- San Francisco, California: (415) 285-1041 or fbi_hotline@nlgsf.org

- Seattle, Washington: (206) 658-7963

National Hotline

If you are located in an area with no hotline, you can call the following number:

Know Your Rights Materials

The NLG maintains a library of basic Know-Your-Rights guides.

- Know Your Rights During Covid-19

- You Have The Right To Remain Silent: A Know Your Rights Guide for Encounters with Law Enforcement

- Operation Backfire: For Environmental and Animal Rights Activists

WEBINAR: Federal Repression of Activists & Their Lawyers: Legal & Ethical Strategies to Defend Our Movements: presented by NLG-NYC and NLG National Office

We also recommend the following resources:

Center for Constitutional Rights

Civil Liberties Defense Center

- Grand Juries: Slideshow

Grand Jury Resistance Project

Katya Komisaruk

Movement for Black Lives Legal Resources

Tilted Scales Collective

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

By Farhad Manjoo, Jan. 26, 2022

Imagine that when your great-grandparents were teenagers, they got their hands on a groundbreaking new gadget, the world’s first fully immersive virtual-reality entertainment system. These weren’t those silly goggles you see everywhere now. This device was more Matrix-y — a stylish headband stuffed with electrodes that somehow tapped directly into the human brain’s perceptual system, replacing whatever a wearer saw, heard, felt, smelled and even tasted with new sensations ginned up by a machine.

The device was a blockbuster; magic headbands soon became an inescapable fact of people’s daily lives. Your great-grandparents, in fact, met each other in Headbandland, and their children, your grandparents, rarely encountered the world outside it. Later generations — your parents, you — never did.

Everything you have ever known, the entire universe you call reality, has been fed to you by a machine.

This, anyway, is the sort of out-there scenario I keep thinking about as I ponder the simulation hypothesis — the idea, lately much discussed among technologists and philosophers, that the world around us could be a digital figment, something like the simulated world of a video game.

The idea is not new. Exploring the underlying nature of reality has been an obsession of philosophers since the time of Socrates and Plato. Ever since “The Matrix,” such notions have become a staple of pop culture, too. But until recently the simulation hypothesis had been a matter for academics. Why should we even consider that technology could create simulations indistinguishable from reality? And even if such a thing were possible, what difference would knowledge of the simulation make to any of us stuck in the here and now, where reality feels all too tragically real?

For these reasons, I’ve sat out many of the debates about the simulation hypothesis that have been bubbling through tech communities since the early 2000s, when Nick Bostrom, a philosopher at Oxford, floated the idea in a widely cited essay.

But a brain-bending new book by the philosopher David Chalmers — “Reality+: Virtual Worlds and the Problems of Philosophy” — has turned me into a hard-core simulationist.

After reading and talking to Chalmers, I’ve come to believe that the coming world of virtual reality might one day be regarded as every bit as real as real reality. If that happens, our current reality will instantly be cast into doubt; after all, if we could invent meaningful virtual worlds, isn’t it plausible that some other civilization somewhere else in the universe might have done so, too? Yet if that’s possible, how could we know that we’re not already in its simulation?

The conclusion seems inescapable: We may not be able to prove that we are in a simulation, but at the very least, it will be a possibility that we can’t rule out. But it could be more than that. Chalmers argues that if we’re in a simulation, there’d be no reason to think it’s the only simulation; in the same way that lots of different computers today are running Microsoft Excel, lots of different machines might be running an instance of the simulation. If that was the case, simulated worlds would vastly outnumber non-sim worlds — meaning that, just as a matter of statistics, it would be not just possible that our world is one of the many simulations but likely. Chalmers writes that “the chance we are sims is at least 25 percent or so.”

Chalmers is a professor of philosophy at New York University, and he has spent much of his career thinking about the mystery of consciousness. He is best known for coining the phrase “the hard problem of consciousness,” which, roughly, is a description of the difficulty of explaining why a certain experience feels like that experience to the being experiencing it. (Don’t worry if this hurts your head; it’s not called the hard problem for nothing.)

Chalmers says that he began thinking deeply about the nature of simulated reality after using V.R. headsets like Oculus Quest 2 and realizing that the technology is already good enough to create situations that feel viscerally real.

Virtual reality is now advancing so quickly that it seems quite reasonable to guess that the world inside V.R. could one day be indistinguishable from the world outside it. Chalmers says this could happen within a century; I wouldn’t be surprised if we passed that mark within a few decades.

Whenever it happens, the development of realistic V.R. will be earthshaking, for reasons both practical and profound. The practical ones are obvious: If people can easily flit between the physical world and virtual ones that feel exactly like the physical world, which one should we regard as real?

You might say the answer is clearly the physical one. But why? Today, what happens on the internet doesn’t stay on the internet; the digital world is so deeply embedded in our lives that its effects ricochet across society. After many of us have spent much of the pandemic working and socializing online, it would be foolish to say that life on the internet isn’t real.

The same would hold for V.R. Chalmers’s book — which travels entertainingly across ancient Chinese and Indian philosophy to René Descartes to modern theorists like Bostrom and the Wachowskis (the siblings who created “The Matrix”) — is a work of philosophy, and so naturally he goes through a multipart exploration into how physical reality differs from virtual reality.

His upshot is this: “Virtual reality isn’t the same as ordinary physical reality,” but because its effects on the world are not fundamentally different from those of physical reality, “it’s a genuine reality all the same.” Thus we should not regard virtual worlds as mere escapist illusions; what happens in V.R. “really happens,” Chalmers says, and when it’s real enough, people will be able to have “fully meaningful” lives in V.R.

To me, this seems self-evident. We already have quite a bit of evidence that people can construct sophisticated realities from experiences they have over a screen-based internet. Why wouldn’t that be the case for an immersive internet?

This gets to what’s profound and disturbing about the coming of V.R. The mingling of physical and digital reality has already thrown society into an epistemological crisis — a situation where different people believe different versions of reality based on the digital communities in which they congregate. How would we deal with this situation in a far more realistic digital world? Could the physical world even continue to function in a society where everyone has one or several virtual alter egos?

I don’t know. I don’t have a lot of hope that this will go smoothly. But the frightening possibilities suggest the importance of seemingly abstract inquiries into the nature of reality under V.R. We should start thinking seriously about the possible effects of virtual worlds now, long before they become too real for comfort.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

A chunk of Antarctic ice that was one of the biggest icebergs ever seen has met its end near South Georgia. Scientists will be studying its effects on the ecosystem around the island for some time.

By Henry Fountain, Jan. 26, 2022

Perhaps you remember iceberg A68a, which enjoyed a few minutes of fame back in 2017 when it broke off an ice shelf on the Antarctic Peninsula. Hardly your everyday iceberg, it was one of the biggest ever seen, more than 100 miles long and 30 miles wide.

The iceberg drifted slowly through the icy Weddell Sea for a few years, before picking up steam as it entered the Southern Ocean. When last we heard from it, in 2020, it was bearing down on the island of South Georgia in the South Atlantic, a bit shrunken and battered from a journey of more than a thousand miles.

Alas, ol’ A68a is no more. Last year, some 100 miles from South Georgia, it finally did what all icebergs eventually do: thinned so much that it broke up into small pieces that eventually drifted off to nothingness.

In its prime, A68a was nearly 800 feet thick, though all but 120 feet of that was hidden below the waterline.

Ecologists and others had feared that during its journey the iceberg might become grounded near South Georgia. That could have kept the millions of penguins and seals that live and breed there from reaching their feeding areas in the ocean.

That didn’t happen. New research shows that A68a performed more of a drive-by and most likely only struck a feature on the seafloor briefly as it turned and kept going until it broke up.

But the research also revealed another potential threat from the iceberg to ecosystems around South Georgia. As it traveled through the relatively warm waters of the Southern Ocean into the South Atlantic, it melted from below, eventually releasing a huge quantity of fresh water into the sea near the island. The influx of so much fresh water could affect plankton and other organisms in the marine food chain.

The scientists, led by Anne Braakmann-Folgmann, a doctoral student at the Center for Polar Observation and Modeling at the University of Leeds in Britain, used satellite imagery to monitor the shape and location of the iceberg over the course of its journey. (Like other large Antarctic icebergs, it was named according to a convention established by the U.S. National Ice Center, which is a bit less flashy than the one used for hurricanes.)

The imagery showed how the area of the iceberg changed over time. The researchers also determined its thickness using data from satellites that measure ice height. By the time it broke up, Ms. Braakmann-Folgmann said, A68a was more than 200 feet thinner overall.

A68a left its mark. The researchers, whose findings were published in the journal Remote Sensing of Environment, estimated that melting in the vicinity of South Georgia resulted in the release of about 150 billion tons of fresh water. That’s enough to fill an Olympic-size swimming pool 61 million times over, the researchers said, although because the ice was already floating its melting did not contribute to sea-level rise.

Not only is the water fresh, not salty, but it also contains a large amount of iron and other nutrients. Ms. Braakmann-Folgmann is helping another group of researchers, from the British Antarctic Survey, who are trying to determine the ecological effects of the iceberg and the meltwater.

When the iceberg was near South Georgia, scientists with the survey were able to deploy autonomous underwater gliders to take water samples. On the island, they used tracking devices on some gentoo penguins and fur seals, to see whether the presence of the iceberg affected their foraging behavior.

Geraint Tarling, a biological oceanographer with the survey, said that preliminary findings from the tracking data showed that the penguins and seals did not alter foraging routes, as they might have had the iceberg blocked their way or affected their prey.

“At least in the areas of the colonies that we saw, the impacts from the iceberg itself are not as devastating as we first feared,” Dr. Tarling said.

But there is still much data to analyze, Dr. Tarling suggested, especially the water samples. A large influx of fresh water on the surface could affect the growth of phytoplankton, at the lower end of the food change, or it could alter the mix of phytoplankton species available, he said.

Complicating the analysis is that 2020, when the iceberg was nearing South Georgia, also happened to be a bad year for krill, the small crustaceans that are just above phytoplankton in the food chain.

Dr. Tarling said that although A68a did not become grounded, a few other large icebergs have in recent decades. Grounding and dragging of an iceberg can wreak havoc on ecosystems on or near the seafloor, he said.

And climate change could potentially lead to more grounding episodes. Warming is causing parts of the huge Antarctic ice sheets to flow faster toward the ocean, leading to more calving of icebergs that then travel north.

“What we’re looking at is a lot more movement of icebergs that could actually gouge these areas of the sea floor,” Dr. Tarling said.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Ownership of more than 500 acres of a forest in Mendocino County was returned to 10 sovereign tribes who will serve as guardians to “protect and heal” the land.

By Isabella Grullón Paz, Jan. 26, 2022

A portion of the 523 acres of redwood forest in Mendocino County, Calif. Credit...Max Forster/Save the Redwoods League, via Associated Press

Tucked away in Northern California’s Mendocino County, the 523 acres of rugged forest is studded with the ghostlike stumps of ancient redwoods harvested during a logging boom that did away with over 90 percent of the species on the West Coast. But about 200 acres are still dense with old-growth redwoods that were spared from logging.

The land was the hunting, fishing and ceremonial grounds of generations of Indigenous tribes like the Sinkyone, until they were largely driven off by European settlers. On Tuesday, a California nonprofit organization dedicated to conserving and preserving redwoods announced that it was reuniting the land and its original inhabitants.

The group, the Save the Redwoods League, which was able to purchase the forest with corporate donations in 2020, said it was transferring ownership of the 523-acre property to the Intertribal Sinkyone Wilderness Council, a group of 10 native tribes whose ancestors were “forcibly removed” from the land by European American settlers, according to a statement from the league.

The tribes will serve as guardians of the land in partnership with the Save the Redwoods League, which has been protecting and restoring redwood forests since 1918.

“Fundamentally, we believed that the best way to permanently protect and heal this land is through tribal stewardship,” Sam Holder, chief executive of the Save the Redwoods League, said in an interview on Tuesday. “In this process, we have an opportunity to restore balance in the ecosystem and in the communities connected to it.”

For over 175 years, members of the tribes represented by the council did not have access to the sacred land they had used for hunting, fishing and ceremonies.

“It is rare when these lands return to the original peoples of those places,” Hawk Rosales, an Indigenous land defender and a former executive director of the Intertribal Sinkyone Wilderness Council, said in an interview on Tuesday.

“We have an intergenerational commitment and a goal to protect these lands and, in doing so, protecting tribal cultural ways of life and revitalizing them,” he added.

As part of the agreement, the land, known before the purchase as Andersonia West, will be called Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ (pronounced tsih-ih-LEY-duhn), which means “Fish Run Place” in the Sinkyone language.

“Renaming the property Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ lets people know that it’s a sacred place; it’s a place for our Native people,” Crista Ray, a board member of the Sinkyone Council, said in the statement. “It lets them know that there was a language and that there was a people who lived there long before now.”

According to the statement, Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ is a vital addition to conserved lands along the Sinkyone coast, which is about five hours north of San Francisco. The newly acquired land sits west of the Sinkyone Wilderness State Park and north of the Intertribal Sinkyone Wilderness, another protected area, which was acquired by the Sinkyone Council in 1997.

The council’s goal, Mr. Rosales explained, is to connect and expand the redwood forests in the area, which are ecologically and culturally linked, to repair “components of an ecosystem that has been fragmented and that has been threatened” by colonial settlement.

Redwood trees aren’t the only endangered species in the forest. The land is also home to coho salmon, steelhead trout, marbled murrelets (a small seabird) and northern spotted owls — all listed under the Endangered Species Act.

Since 2006, the Redwoods League had been in conversations with a California logging family who had owned the land for generations. Mr. Holder explained that after years of building a relationship with the family, the league was able to purchase the land in 2020 for $3.55 million. The money for the purchase was donated by the Pacific Gas & Electric Company as part of its program to mitigate environmental damage.

The Redwoods League still retains an easement on the property. “Our goal is to just make sure that we are adding to adding capacity and support for the council as they advance their own stewardship and restoration goals,” Mr. Holder explained.

This is the second time the Save the Redwoods League has donated land to the council. In 2012, it transferred a 164-acre property north of Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ, known as Four Corners, to the Sinkyone.

To Mr. Rosales, the importance of piecing together these culturally important lands is not only the conservation of nature, but also allowing tribes to have a stronger connection with their ancestors.

“The descendants of those ancestors are among us today in the member tribes,” Mr. Rosales said. “There are families that trace their lineage to this place, essentially, and the surrounding vicinity. They are connected to their ancestors, and this is a way of reaffirming that.”

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Media Release

January 26, 2022

Contact: Carole Seligman

Phone: (415) 483-4428

caroleseligman@sbcglobal.net

International Webinar February 1, 2022

1:00pm SF, 4:00pm NYC, 6:00pm Rio de Janeiro, 9:00pm London, 11:00pm Johannesburg, 6:00am Tokyo

Register Now https://bit.ly/iwa-2022

More on the Campaign:

https://www.facebook.com/IWAFAPP/

Endorse Call-to-Action:

https://forms.gle/ijBocFw5zBx6AP28A

Email: InternationalWorkersAction@gmail.com

British Labour Activists Support Feb. 1 International Forum and Call to Free Mumia and All Political Prisoners

For decades, innocent and framed political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal and other Black Panthers and anti-imperialist prisoners have been imprisoned, often in solitary confinement, for challenging American racism, capitalism and imperialism. Mumia is the most internationally well-known of these aging political prisoners, who are victims of repressive government programs such as the FBI’s COINTELPRO. Many of them are critically ill. All of these political prisoners need to be released immediately.

To win the freedom of these political prisoners, international working-class action is necessary. In 1999, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) led an exemplary action shutting down all West Coast ports and led a massive march of 25,000 in San Francisco chanting: “An Injury to One is an Injury to All – Free Mumia Abu-Jamal!”

In March 2021, the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA) – the largest union in South Africa, with 338,000 members called for a renewed global campaign to Free Mumia Abu-Jamal. In June, the ILWU Convention voted to support NUMSA’s campaign. Inspired by NUMSA’s initiative, an International Forum is organized on February 1, 2022 to build for an International Day of Workers Action to free all these political prisoners Initiated by the Labor Action Committee to Free Mumia Abu-Jamal and the Black Panther Party Commemoration Committee (New York City, New England and South).

SUPPORT FOR FEB. 1 INTERNATIONAL FORUM AND CALL TO ACTION

Having been informed that an online meeting for international workers' action will be held on 1 February, we support this initiative and call for a day of international workers' solidarity with Mumia Abu Jamal.

We, the undersigned British labour activists, including some who have fought for decades for Mumia's release, have learned that new evidence recently discovered in 6 boxes confirms what we have been saying all along: Mumia Abu Jamal was the victim of a frame-up, a rigged and racist trial. We believe that this overwhelming evidence should lead the US authorities to release Mumia Abu Jamal immediately.

ENDORSERS

Tariq Ali, writer; Ian Hodson, National President, Bakers Union - BFAWU; Steve Hedley, Senior Assistant General Secretary, Rail Workers Union - RMT; Jane Doolan, UNISON NEC member; Mike Calvert, Deputy Branch Secretary, Islington UNISON; Stefan Cholewka, Secretary, Greater Manchester Association of Trade Union Councils (GMATUC); Margaret K. Taylor, Treasurer, Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Trades Council; Explo Nani-Kofi, Convenor, Moving Africa Panafricanist Organization Ghana / Member South Dayi District Assembly, Editor Another Africa Is Possible Newsletter and Kilombo Journal; John Sweeney, Labour and trade union activist; Charles Charalambous, former President, Torbay and South Devon Trades Union Council, Editor Labour Internationalist; Paul Filby, Liverpool, Blacklist Support Group; Nick Phillips, UNITE member, London; Henry Mott, UNITE member; Sussan Rassoulie, Islington Unison Branch Committee member; Antony Rimmer, Liverpool 47 Surcharged Councillor, Merseyside Pensioners Association, trade unionist (CWU and Unite); Richard Gill, Islington UNISON; Jo Rust, Secretary, King’s Lynn and District Trades Council and Independent Borough Councillor in King’s Lynn; Mike Arnott, Secretary, Dundee Trades Council; Doreen McNally, Liverpool Unite Community branch and former spokesperson, Women of the Waterfront; Audrey White, Merseyside Pensioners Association

OTHER NEW INTERNATIONAL ENDORSEMENTS

All Pakistan Trade Union Federation

Democracia Socialista de Puerto Rico

DIP (Revolutionary Workers Party), Turkey

International Workers Committee Against War and Exploitation (IWC)

Partido Obrero (Workers Party) of Argentina

Workers Revolutionary Party of Greece (EEK)

More on the Campaign:

https://www.facebook.com/IWAFAPP/

Endorse Call-to-Action:

https://forms.gle/ijBocFw5zBx6AP28A

Email: InternationalWorkersAction@gmail.com

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

By Jamelle Bouie, Jan. 28, 2022

The historian Marcus Rediker opens “The Slave Ship: A Human History” with a harrowing reconstruction of the journey, for a captive, from shore to ship:

The ship grew larger and more terrifying with every vigorous stroke of the paddles. The smells grew stronger and the sounds louder — crying and wailing from one quarter and low, plaintive singing from another; the anarchic noise of children given an underbeat by hands drumming on wood; the odd comprehensible word or two wafting through: someone asking for menney, water, another laying a curse, appealing to myabecca, spirits.

An estimated 12.5 million people endured some version of this journey, captured and shipped mainly from the western coast of Africa to the Western Hemisphere during the four centuries of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Of that number, about 10.7 million survived to reach the shores of the so-called New World.

It is thanks to decades of painstaking, difficult work that we know a great deal about the scale of human trafficking across the Atlantic Ocean and about the people aboard each ship. Much of that research is available to the public in the form of the SlaveVoyages database. A detailed repository of information on individual ships, individual voyages and even individual people, it is a groundbreaking tool for scholars of slavery, the slave trade and the Atlantic world. And it continues to grow. Last year, the team behind SlaveVoyages introduced a new data set with information on the domestic slave trade within the United States, titled “Oceans of Kinfolk.”

The systematic effort to quantify the slave trade goes back at least as far as the 19th century. For example, in the 1888 edition of the second volume of his “History of the United States of America, from the Discovery of the American Continent,” the historian George Bancroft estimates “the number of negroes” imported by “the English into the Spanish, French, and English West Indies, and the English continental colonies, to have been, collectively, nearly three million: to which are to be added more than a quarter of a million purchased in Africa, and thrown into the Atlantic on passage.” He adds later, “After every deduction, the trade retains its gigantic character of crime.”

In 1958, the historians Alfred H. Conrad and John R. Meyer transformed the study of slavery — and of economic history more broadly — with the publication of “The Economics of Slavery in the Ante Bellum South.” Their methods, which relied on statistical data and mathematical analysis, revolutionized the field.

The origins of SlaveVoyages lie in this period and, specifically, in the work of a group of scholars who, a decade later, began to collect data on slave-trading voyages and encode it for use with a mainframe computer.

“It goes back to the late 1960s and the work of Philip Curtin,” David Eltis, an emeritus professor of history at Emory and a former co-editor of the SlaveVoyages database, told me. “He did this book called ‘The Atlantic Slave Trade: A Census,’ part of which involved computerizing — which was quite a dramatic step in those days — a list of slave voyages for the 19th century. And he sent me, in response to a cold call, a box of two thousand three-hundred and thirteen IBM cards, one card for each voyage. And that was the starting point.”

Over the next two decades, working independently and collaboratively, historians in the United States and around the world would turn this archival information on the trans-Atlantic trade into data sets representing more than 11,000 individual voyages, a significant accomplishment even if it represented only a fraction of the trade in human lives from the 15th century to its end in the 19th century.

Later, beginning in the 1990s, those scholars began to integrate this data — which encompassed the British, Dutch, French and Portuguese slave trade — into a single data set. By the end of the decade, the first SlaveVoyages database had been released to the public as an (expensive) CD-ROM set including details from more than 27,000 voyages.

It is hard to exaggerate the significance of this work for historians of slavery and the slave trade. An arrival to and departure from port tells a story. To know when, where and how many times a ship disembarked is to know a little more about the nature of the specific exchange as well as the slave trade as a whole. Every bit of new information fills in the blanks of a time that has long since passed out of living memory.

After nearly 10 years as physical media, SlaveVoyages was introduced to the public as a website in 2008 and then relaunched in 2019 with a new interface and even more detail. As it stands today, the site, funded primarily by grants, contains data sets on various aspects of the slave trade: a database on the trans-Atlantic trade with more than 36,000 entries, a database containing entries on voyages that took place within the Americas and a database with the personal details of more than 95,000 enslaved Africans found on these ships.

The newest addition to SlaveVoyages is a data set that documents the “coastwise” traffic to New Orleans during the antebellum years of 1820 to 1860, when it was the largest slave-trading market in the country. The 1807 law that forbade the importation of enslaved Africans to the United States also required any captain of a coastwise vessel with enslaved people on board to file, at departure and on arrival, a manifest listing those individuals by name.

Countless enslaved Africans arrived at ports up and down the coast of the United States, but the largest share were sent to New Orleans. This new data set draws from roughly 4,000 “slave manifests” to document the traffic to that port. Those manifests list more than 63,000 captives, including names and physical descriptions, as well as information on an individual’s owner and information on the vessel and its captain.

Because of its specificity with regard to individual enslaved people, this new information is as pathbreaking for lay researchers and genealogists as it is for scholars and historians. It is also, for me, an opportunity to think about the difficult ethical questions that surround this work: How exactly do we relate to data that allows someone — anyone — to identify a specific enslaved person? How do we wield these powerful tools for quantitative analysis without abstracting the human reality away from the story? And what does it mean to study something as wicked and monstrous as the slave trade using some of the tools of the trade itself?

Before we go any further, it is worth spending a little more time with the history of the trans-Atlantic slave trade itself, at least as it relates to the United States.

A large majority of people taken from Africa were sold to enslavers in either South America or the Caribbean. British, Dutch, French, Spanish and Portuguese traders brought their captives to, among other places, modern-day Jamaica, Barbados, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Brazil and Haiti, as well as Argentina, Antigua and the Bahamas. A little over 3.5 percent of the total, about 389,000 people, arrived on the shores of British North America and the Gulf Coast during those centuries when slave ships could find port.

In the last decades of the 18th century, moral and religious activism fueled an effort to suppress British involvement in the African slave trade. In 1774, the Continental Congress of rebelling American states adopted a temporary general nonimportation policy against Britain and its possessions, effectively halting the slave trade, although the policy lapsed under the Confederation Congress in the wake of the Revolutionary War. Still, by 1787, most of the states of the newly independent United States had banned the importation of slaves, although slavery itself continued to thrive in the southeastern part of the country.

From 1787 to 1788, Americans would write and ratify a new Constitution that, in a concession to Lower South planters who demanded access to the trans-Atlantic trade, forbade a ban on the foreign slave trade for at least the next 20 years. But Congress could — and, in 1794, did — prohibit American ships from participating. In 1807, right on schedule, Congress passed — and President Thomas Jefferson, a slave-owning Virginian, signed — a measure to abolish the importation of enslaved Africans to the United States, effective Jan. 1, 1808.

But the end to American involvement in the trans-Atlantic slave trade (or at least the official end, given an illegal trade that would not end until the start of the Civil War) did not mean the end of the slave trade altogether. Slavery remained a big and booming business, driven by demand for tobacco, rice, indigo and increasingly cotton, which was already on its path to dominance as the principal cash crop of the slaveholding South.

Within a decade of the invention of the cotton gin in 1793, annual cotton production had grown twentyfold to 35 million pounds in 1800. By 1810, production had risen to roughly 85 million pounds per year, accounting for more than 20 percent of the nation’s export revenue. By 1820, the United States was producing something in the area of 160 million pounds of cotton a year.

Fueling this growth was the rapid expansion of American territory, facilitated by events abroad. In August 1791, the Haitian Revolution began with an insurrection of enslaved people. In 1803, Haitian revolutionaries defeated a final French Army expedition sent to pacify the colony after years of bloody conflict. To pay for this expensive quagmire — and to keep the territory out of the hands of the British — the soon-to-be-emperor Napoleon Bonaparte sold what remained of French North America to the United States at a fire-sale price.

The new territory nearly doubled the size of the country, opening new land to settlement and commercial cultivation. And as the American nation expanded further into the southeast, so too did its slave system. Planters moved from east to west. Some brought slaves. Others needed to buy them. There had always been an internal market for enslaved labor, but the end of the international trade made it larger and more lucrative.

It is hard to quantify the total volume of sales on the domestic slave trade, but scholars estimate that in the 40-year period between the Missouri Compromise and the secession crisis, at least 875,000 people were sent south and southwest from the Upper South, most as a result of commercial transactions, the rest as a consequence of planter migration.

New, more granular data on voyages and migrations and sales will help scholars delve deeper than ever into the nature of slavery in the United States, into specifics of the trade and into the ways it shaped the political economy of the American republic.

But no data, no matter how precise, is complete. There are things that quantification can obscure. And there are, again, ethical questions that must be asked and answered when dealing with the quantitative study of human atrocity, which is what we’re ultimately doing when we bring statistical and mathematical methods to the study of slavery.

To think about the slave trade in terms of vessels and voyages — to look at it as columns in a spreadsheet or as points in an online animation — is to engage in an act of abstraction. Historians have no choice but to rely, as Marcus Rediker writes, on “ledgers and almanacs, balance sheets, graphs and tables.” But it carries a heavy cost, dehumanizing a reality that, he writes, “must, for moral and political reasons, be understood concretely.”

Consider, as well, the extent to which the tools of abstraction are themselves tied up in the history of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. As the historian Jennifer L. Morgan notes in “Reckoning With Slavery: Gender, Kinship, and Capitalism in the Early Black Atlantic,” the fathers of modern demography, the 17th-century English writers and mathematicians William Petty and John Graunt, were “thinking through problems of population and mobility at precisely the moment when England had solidified its commitment to the slave trade.”

Their questions were ones of statecraft: How could England increase its wealth? How could it handle its surplus population? And what would it do with “excessive populations that did not consume” in the formal market? Petty was concerned with Ireland — Britain’s first colony, of sorts — and the Irish. He thought that if they could be forcibly transferred to England, then they could, in Morgan’s words, become “something valuable because of their ability to augment the population and labor power of the English.”

This conceptual breakthrough, Morgan told me in an interview, cannot be disentangled from the slave trade. The English, she said, “are learning to think about people as ‘abstractable.’ By watching what the Spanish and what the Portuguese have been doing for 200 years, but also by doing it themselves, saying, ‘Oh, I can take Africans from here and move them to there, and then I can use them for my own purposes.’”

Embedded in this early project of quantification — Morgan notes in her book that Graunt “mounted what historians and political scientists agree was the first systematic use of demographic evidence to understand a contemporary sociopolitical problem” — is an objectification of human life.

Compounding these problems is the extent to which we rely on the documentation of slaveholders for our knowledge of the enslaved.

Writing of enslaved women on Barbados, the historian Marisa J. Fuentes notes in “Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive” that “they appear as historical subjects through the form and content of archival documents in the manner in which they lived: spectacularly violated, objectified, disposable, hypersexualized, and silenced. The violence is transferred from the enslaved bodies to the documents that count, condemn, assess, and evoke them, and we receive them in this condition.”

She continues: “Epistemic violence originates from the knowledge produced about enslaved women by white men and women in this society, and that knowledge is what survives in archival form.”

The traders, enslavers, officials and others who documented the slave trade did so in the context of legal and commercial relationships. For them, the enslaved were objects to be bought and sold for profit, wealth and status. If an individual’s “historical” life is shaped by the documents and images they leave behind, then, as Fuentes writes, most enslaved women, men and children live (and have lived) their historical lives as “numbers on an estate inventory or a ship’s ledger.” It is in that form that they are then shaped by “additional commodification” — used but not necessarily understood as having been fully alive.

“The data that we have about those ships is also kind of caught in a stranglehold of ship captains who care about some things and don’t care about others,” Jennifer Morgan said. We know what was important to them. It is the task of the historian to bring other resources to bear on this knowledge, to shed light on what the documents, and the data, might obscure.

“By merely reproducing the metrics of slave traders,” Fuentes said, “you’re not actually providing us with information about the people, the humans, who actually bore the brunt of this violence. And that’s important. It is important to humanize this history, to understand that this happened to African human beings.”

It’s here that we must engage with the question of the public. Work like the SlaveVoyages database exists in the “digital humanities,” a frequently public-facing realm of scholarship and inquiry. And within that context, an important part of respecting the humanity of the enslaved is thinking about their descendants.

“If you’re doing a digital humanities project, it exists in the world,” said Jessica Marie Johnson, an assistant professor of history at Johns Hopkins and the author of “Wicked Flesh: Black Women, Intimacy, and Freedom in the Atlantic World.” “It exists among a public that is beyond the academy and beyond Silicon Valley. And that means that there should be certain other questions that we ask, a different kind of ethics of care and a different morality that we bring to things.”

I have some personal experience with this. Years ago, I worked with colleagues at Slate magazine on an infographic that showed the scale and duration of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, using data from the SlaveVoyages website. Plotted on a map of the Atlantic Ocean, it represented each ship as a single dot, moving from its departure point on the African coast to its arrival point in the Americas. As time goes on — as the 16th century becomes the 17th century becomes the 18th century becomes the 19th century — the dots grow overwhelming.

What I did not appreciate at the time was how we, the creators, would lose control of our creation. People encountered the infographic in ways we could not anticipate and that lay outside of our imagination. It was repurposed for schools and museums, used for personal projects and in exhibitions. Inevitably, some of these people would contact us. They would want to know more: about the ships, about the journeys, about the people. And we couldn’t answer them.

When I think back to the creation of that infographic, I wonder whether we had shown the care demanded of the data. Whether we had, in creating this abstraction, re-enacted — however inadvertently — some of the objectification of the slave trade.

One way to address this problem is to ensure that the audience understands the context. “I want to make sure that Black people in the audience feel like they are not being assaulted again by the information in the project or by the methods behind the project or any of that,” Johnson said, speaking of SlaveVoyages and other public work around slavery. “Everything from the colors on a website to the metadata itself is reshaped if we decide that the people in the audience should not feel harmed” and “should not be re-assaulted by their experience in this project or on this site.”

The new addition to SlaveVoyages, “Oceans of Kinfolk,” was made with these questions and concerns in mind. “You can use quantitative methodologies to learn about enslaved people, to learn about their experience,” said Jennie Williams, who collected and compiled the data as a doctoral student at Johns Hopkins and helped integrate it into the database as a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Williams is also a friend, with whom I have discussed this work for years.

The slave traders who documented their cargo for federal authorities — producing the manifests that were the foundation of Williams’s work — were obviously not interested in the lives and experiences of their captives, except as cargo. They had no intention of preserving their identities as people. But despite this indifference, Williams said, that is essentially what happened.

These records are unique, Williams explained. If you look at bills of sale, she said, “most people are not identified by last name. If you look at fugitive ads, which I looked at 11,000 of and did a comparison with the manifests, which is also my dissertation, most people are not listed by last name. That is because slaveholders did not recognize enslaved people’s last names. They knew they had last names — they did not care.”

But, she continued: “If you asked an enslaved person ‘what is your name,’ they responded with a first and last name much more commonly than you would see in the other records. And so, manifests, compared to all other records of enslaved people I’ve seen, have a much higher proportion of last names in them.”

That fact makes this data important for genealogists and others interested in their family histories. “If Black families are able to reach or to trace their genealogy back to the 19th century, they very rarely get past 1870,” the year of the first federal census after slavery, Williams said. “This is not a database of everybody, but if I can get people to know about it, it is potentially useful for millions of people, because 63,000 people have millions of descendants.”

David Eltis concurred. “It’s quite rare to have this big body or big cache of names for enslaved people in the United States,” he said. “A person can go back and find something from the early 19th century, find a person with a possible connection. And that is simply not possible for the trans-Atlantic material. You can’t go back to Africa.”

If part of the ethical task for quantitative researchers of slavery is to preserve the humanity of the enslaved despite the nature of the sources, then connecting this data to Black genealogists is one way to underscore the fact that these were real people with real legacies.

“I could barely sleep the first night,” said Carlton Houston, a descendant of one of the 63,000 captives listed as part of the coastal trade to New Orleans, speaking of when he first saw the document listing his ancestor Simon Wilson, a young man sold for the purpose of “breeding” more people. “It was so compelling to see. Here’s the manifest, here’s this name, to have this visual in your head of these young people, chained on a boat, not really knowing where they were going.”

“There was not much for him to look forward to, you know, just this abysmal world that they lived in,” Houston added. “And yet, they survived, and didn’t give up.”

As for the sources themselves, it may be possible to use their physicality — the fact that these ledger books, bills of sale and fugitive slave ads are real, tangible objects — to tell stories about the humans involved in this centuries-long nightmare, to use the means of objectifying others to undermine the objectification itself.

“There is a strange way in which the everydayness of the document helps you understand the extraordinary imbalance of power and the wrongness,” Walter Johnson, a professor of history and African and African American studies at Harvard, said. “If somebody smudges the ink on a ledger, you have to imagine a person writing that. And once you imagine a person writing that, you’re imagining the extraordinary power that those words on a page have over somebody’s life. That somebody’s life and their lineage is actually being conveyed by that errant pen stroke. And then that takes you to a moment where you have to imagine those people.”

Indeed, the very banality of this material can help us understand how this system survived, and thrived, for so long. “I am not a historian of slavery because I want to spend my time understanding massive moments of spectacular violence,” Jennifer Morgan told me. “I actually want to understand tiny moments of violence, because that’s what I see as adding up to a kind of numbness — a numbness of empathy, a numbness to human interconnection.”

All of this is to say that with the history of slavery, the quantitative and the qualitative must inform each other. It is important to know the size and scale of the slave trade, of the way it was standardized and institutionalized, of the way it shaped the history of the entire Atlantic world.

But as every historian I spoke to for this story emphasized, it is also vital that we have an intimate understanding of the people who were part of this story and specifically of the people who were forced into it. It is for good reason that W.E.B. Du Bois once called the trans-Atlantic slave trade “the most magnificent drama in the last thousand years of human history”; a tragedy that involved “the transportation of 10 million human beings out of the dark beauty of their mother continent into the newfound Eldorado of the West” where they “descended into Hell”; and an “upheaval of humanity like the Reformation and the French Revolution.”

The future of SlaveVoyages will include even more information on the people involved in the slave trade, enslaved and enslavers alike. “We would like to add an intra-African slave trade database because there is a lot of movement of enslaved people on the eastern side of the Atlantic,” David Eltis said. He also told me that he can imagine a merger with scholars documenting the slave trade across the Indian Ocean, the roots of which go back to antiquity and whose more modern form was concurrent with the trans-Atlantic trade. “We’re really leaning into territory which was unimaginable back in 1969,” he said.

We may not have many statues of the enslaved — we may not have anywhere near enough letters and portraits and personal records for the millions who lived and died in bondage — but they were living, breathing individuals nonetheless, as real to the world as the men and women we put on pedestals.

As we learn from new data and new methods, it is paramount that we keep the truth of their essential humanity at the forefront of our efforts. We must have awareness, care and respect, lest we recapitulate the objectification of the slave trade itself. It is possible, after all, to disturb a grave without ever touching the soil.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

The stories of those who died in custody offer an intimate, firsthand look at the crisis gripping the New York City jail system.

By Michael Wilson and Chelsia Rose Marcius, Jan. 28, 2022

The first to die last year was found in January, hanging from a sprinkler head in his jail cell just a week after his arrival. The second was found strangled about a month later, his head forced through a slot in his cell door in what was later ruled a suicide.

The weeks and months that followed brought more deaths in New York City’s Rikers Island jail complex. Another hanging, in a shower cell used for washing off pepper spray; an overdose on drugs that aren’t supposed to be in jails. A sudden medical emergency. A bout of viral meningitis. A case of Covid-19.

At least 16 people died in the custody of New York’s troubled jails in 2021. Most were awaiting trial and died on Rikers Island, the notorious 90-year-old warren of cellblocks separated from the city’s mainland by the East River.

The deaths have received outsize scrutiny compared with years past, with many seemingly preventable, especially after recent reforms put in place at the jails and the emptying of thousands of inmates during the pandemic. Inmates were found hanging from the ends of makeshift nooses or slumped from drug overdoses in a place with a basic responsibility to keep each inmate safe from harm, pending trial or release.

These men make up a tragic fraternity of strangers, linked by their common ends. Some were past middle age, others in their prime. More than a few fought crippling addictions. Many had lifelong mental health issues. One was a handyman. Another a new father. A third was an attentive son. There was also a serial thief, a stalking suspect and a man accused of threatening to inject a stranger with H.I.V.

There have been worse years at Rikers: In 2013 there were 23 deaths, and that number routinely rose above 30 in the 1990s. In 1990 alone, 96 inmates died in custody. But last year’s number is striking in light of how steeply the jail population had declined in 2020 compared with previous years, when the system often held at least twice as many people. The population rose gradually in 2021, ending the year at prepandemic levels but still far below the 1990s and early 2000s.

All but one of those who died were Black or Hispanic. They faced a constellation of charges, from parole violations to robbery, assault, even murder. At least six died by suicide, and at least three others by overdose. Most of the deaths might have been prevented by basic oversight, but since the beginning of the pandemic, jail employees had been overworked and reporting sick and staying away by the hundreds.

Awaiting the outcomes of their cases, these men died unseen, away from family and, in most cases, from doctors or correction officers charged with watching over them.

‘I don’t think I’m going to make it’

Stephan Khadu was a healthy 22-year-old when he was locked up in December 2019 on charges of conspiracy to commit murder. At the height of the pandemic, he defended the jail’s officers when his mother, Lezandre Khadu, 39, would criticize them.

“He’d say, ‘Mom, what is wrong with you? They work three or four tours,’” Ms. Khadu said, describing a time her son shared a commissary pastry with a hungry officer.

But he also related frequent encounters with officers wielding the potent Cell Buster pepper spray that they carry on their belts. He told her they sprayed it so often that he had gotten used to it.

By this past summer, after 20 months in jail, Mr. Khadu began suffering seizures, which his mother said he had never had before. In September, he was being held at the Vernon C. Bain Correctional Center, a floating jail barge just north of Rikers Island. Another inmate found him bleeding from the mouth and helped Mr. Khadu to his feet. They went for help but were met by officers who were dealing with a fire in another cell, and the officers pepper-sprayed the two inmates, Ms. Khadu said.

Her son was hospitalized that day for his seizures and died. He was 24 years old, the 12th inmate to die in 2021. “He is not just ‘Number 12,’” Ms. Khadu said. “He is a son, he is a brother, he is a father, he is a grandson, he is a nephew.”

The city medical examiner ruled that Mr. Khadu had died a natural death caused by a meningitis infection, probably viral, raising questions about the medical treatment he received in custody.

Victor Mercado, an older man who died in Rikers, was also supposed to be receiving medical care there. Forced by poor circulation to use a wheelchair, Mr. Mercado had been held in a jail infirmary since he was arrested in July on a gun charge.

In telephone calls from the jail, Mr. Mercado, a Bronx handyman with a heroin habit, told his childhood friend Ray Rivera that the system was taking few precautions against the spread of Covid and that he was afraid of getting sick, Mr. Rivera said.

“He said, ‘Listen, they’re putting mad sick people in here, everybody’s on top of each other,’” Mr. Rivera recalled.

When Mr. Mercado caught the virus, Mr. Rivera urged him to stay positive, but his friend’s outlook was darkening. “He said real clear, ‘I don’t think I’m going to make it,’” Mr. Rivera said.

That was on a Sunday. Mr. Mercado died the following Friday, Oct. 15 — about two weeks after his 64th birthday.

That same week, a 58-year-old autistic man with a lengthy arrest history named Anthony Scott was once again in custody, accused of punching a hospital nurse in the face. He had been locked up dozens of times since his 20s, but this time, as he was about to be transferred from a Manhattan holding pen to Rikers Island, Mr. Scott hanged himself — death number 14.

‘A crisis for persons in custody’

New York City’s jail system has long struggled to prevent people in custody from harming themselves.

On the day Mr. Scott died, the city Board of Correction, a jail oversight panel, issued a report that described failures in a case of attempted suicide and noted that the breakdowns had become increasingly problematic after the pandemic began.

In November 2020, an inmate hanged himself in the Manhattan Detention Center while a correction captain stood by and forbade a subordinate from intervening, prosecutors said when they later charged the captain with criminally negligent homicide.

That was one in a soaring number of episodes of self-harm in the jail system since the beginning of the pandemic, and a foreshadowing of what would occur in 2021. By last September, at least five suicides had taken place in the previous nine months after more than two years without any, prompting the Correction Board to declare “a crisis for persons in custody.” At least one more suicide would follow, and yet another death — still under investigation — seems likely also to have been a case of self-harm.

Inmates with histories of self-harm are usually flagged for special observation. But a lack of direct supervision from the staff led to conditions that allowed men to take their lives in several cases last year.

Javier Velasco of Queens was described as a loving husband but protective to a fault — he wouldn’t let his wife go to the grocery alone. When he drank, these qualities hardened and darkened, turning him menacing and violent, said his widow, Amanda Velasco.

She filed for divorce in what she said was an empty threat aimed at changing his ways. Then late last February, Ms. Velasco told the police that Mr. Velasco had broken into her apartment, stolen property and sent her threatening texts. He was arrested and sent to Rikers and, in March, he told her she was safer without him. Then he hanged himself. He was 37.

“He loved me and he loved my children. He did everything for us — everything,” Ms. Velasco said. “He’s not just this crazy obsessed man.”

Another inmate, Segunda Guallpa, married and started a family in Ecuador before moving to New York in 1988. He was hurt in a construction accident and, when the family lost their home last year, began drinking heavily, which made him abusive, one of his sons, Francisco Guallpa, said. In August, after having been arrested on charges of domestic violence, he took his life in Rikers Island. He was 58.

“When he was sober, he was a perfect father,” Francisco said. “He was always there, cooking, taking care of us. He was very attentive. He must’ve just been desperate in the end.”

Brandon Rodriguez, 25, had fled New York City when the coronavirus arrived, moving to Indiana, where he worked at a Wendy’s. “He was doing good,” said his mother, Tamara Carter, 44. “I wish he’d stayed there.”

He was given a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis and returned to New York, where his troubles with the law, which had begun before the Indiana move, resumed, his mother said. He had struggled with mental illness since he was a boy, she said, and he had gone off his medication in recent months.

He was arrested on domestic violence charges in August. Six days later he was found hanging in a shower cell where inmates are sent to wash off the Cell Buster spray.

‘Not just a detainee’