International Webinar — February 1, 2022

Register: https://bit.ly/iwa-2022

1:00pm SF, 4:00pm NYC, 6:00pm Rio de Janeiro, 9:00pm London, 11:00pm Johannesburg, 6:00am Tokyo

Recent Organizational Endorsers Include:

Alameda Labor Council, UNITE (UK), Alameda County Council Green Party, Democracia Socialista de Puerto Rico, National Alumni Association of the Black Panther Party, Oscar Grant Committee against Police Brutality and State Repression, San Francisco Bay Area IWW General Membership Branch

https://www.facebook.com/IWAFAPP/

InternationalWorkersAction@gmail.com

Endorse: https://forms.gle/ijBocFw5zBx6AP28A

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Take a Stand for Reproductive Justice

Rally to Control Our Bodies

Saturday, January 22, 11:30 A.M.

Phillip Burton Federal Building

450 Golden Gate, San Francisco

12:30 P.M. March to Civic Center (1 block)

1:30 P.M. Speak out for Reproductive Justice @ Civic Center

Oppose “Walk for Life”

reprojusticenow.org

January 22 is the anniversary of the historic Roe v. Wade decision that legalized abortion. Almost fifty years later, this law may be overturned unless the movement that won it is rebuilt. The majority is for abortion rights, so now is the time to show up and fight to keep this right.

The National Mobilization for Reproductive Justice calls on all feminists, LGBTQ+ activists, working people, and defenders of human rights to come out and fight for the full range of issues that comprise reproductive justice. All people must be able to control their bodies!

We will also be a counter-presence at the anti-abortion “Walk for Life” rally before our 1:30 P.M. Speak Out for Reproductive Justice.

For more information, to endorse or get involved, contact 415-864-1278 or reprojustice.sf@gmail.com

For the full list of demands, use the link below to visit:

National Mobilization for Reproductive Justice

reprojusticenow.org

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

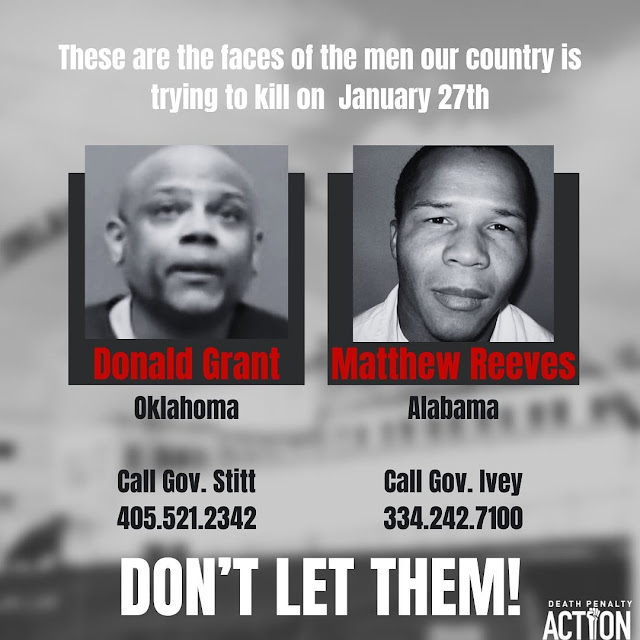

The Ahmadi Family Drone Massacre, August 29, 2021…..We will not forget

United in Action to STOP KILLER DRONES:

SHUT DOWN CREECH! Spring Action, 2022

March 26 - April 2—Saturday to Saturday

Co-sponsored by CODEPINK and Veterans For Peace

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

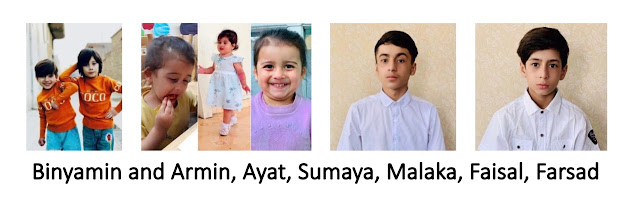

Screenshot of Kevin Cooper's artwork from the teaser. “In His Defense” The People vs. Kevin Cooper

A film by Kenneth A. Carlson

Teaser is now streaming at:

https://www.carlsonfilms.com

Posted by: Death Penalty Focus Blog, January 10, 2022

https://deathpenalty.org/teaser-for-a-kevin-cooper-documentary-is-now-streaming/?eType=EmailBlastContent&eId=1c7299ab-018c-4780-9e9d-54cab2541fa0

“In his Defense,” a documentary on the Kevin Cooper case, is in the works right now, and California filmmaker Kenneth Carlson has released a teaser for it on CarlsonFilms.com

Just over seven months ago, California Gov. Gavin Newsom ordered an independent investigation of Cooper’s death penalty case. At the time, he explained that, “In cases where the government seeks to impose the ultimate punishment of death, I need to be satisfied that all relevant evidence is carefully and fairly examined.”

That investigation is ongoing, with no word from any of the parties involved on its progress.

Cooper has been on death row since 1985 for the murder of four people in San Bernardino County in June 1983. Prosecutors said Cooper, who had escaped from a minimum-security prison and had been hiding out near the scene of the murder, killed Douglas and Peggy Ryen, their 10-year-old daughter, Jessica, and 10-year-old Chris Hughes, a friend who was spending the night at the Ryen’s. The lone survivor of the attack, eight-year-old Josh Ryen, was severely injured but survived.

For over 36 years, Cooper has insisted he is innocent, and there are serious questions about evidence that was missing, tampered with, destroyed, possibly planted, or hidden from the defense. There were multiple murder weapons, raising questions about how one man could use all of them, killing four people and seriously wounding one, in the amount of time the coroner estimated the murders took place.

The teaser alone gives a good overview of the case, and helps explain why so many believe Cooper was wrongfully convicted.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

To: U.S. Senate, U.S. House of Representatives

End Legal Slavery in U.S. Prisons

Sign Petition at:

https://diy.rootsaction.org/petitions/end-legal-slavery-in-u-s-prisons

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

On the anniversary of the 26th of July Movement’s founding, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research launches the online exhibition, Let Cuba Live. 80 artists from 19 countries – including notable cartoonists and designers from Cuba – submitted over 100 works in defense of the Cuban Revolution. Together, the exhibition is a visual call for the end to the decades-long US-imposed blockade, whose effects have only deepened during the pandemic. The intentional blocking of remittances and Cuba’s use of global financial institutions have prevented essential food and medicine from entering the country. Together, the images in this exhibition demand: #UnblockCuba #LetCubaLive

Please contact art@thetricontinental.org if you are interested in organising a local exhibition of the exhibition.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Rashid just called with the news that he has been moved back to Virginia. His property is already there, and he will get to claim the most important items tomorrow. He is at a "medium security" level and is in general population. Basically, good news.

He asked me to convey his appreciation to everyone who wrote or called in his support during the time he was in Ohio.

His new address is:

Kevin Rashid Johnson #1007485

Nottoway Correctional Center

2892 Schutt Road

Burkeville, VA 23922

www.rashidmod.com

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Freedom for Major Tillery! End his Life Imprisonment!

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

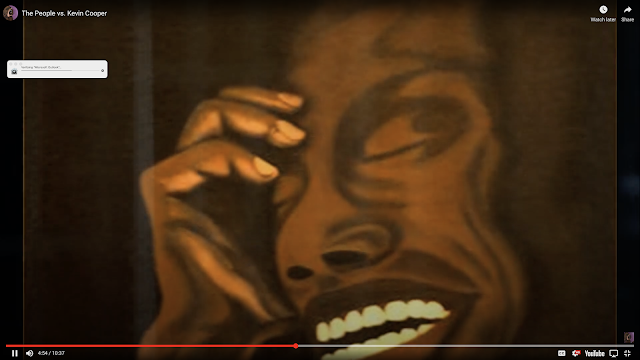

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

Contact: Governor's Press Office

Friday, May 28, 2021

(916) 445-4571

Governor Newsom Announces Clemency Actions, Signs Executive Order for Independent Investigation of Kevin Cooper Case

SACRAMENTO – Governor Gavin Newsom today announced that he has granted 14 pardons, 13 commutations and 8 medical reprieves. In addition, the Governor signed an executive order to launch an independent investigation of death row inmate Kevin Cooper’s case as part of the evaluation of Cooper’s application for clemency.

The investigation will review trial and appellate records in the case, the facts underlying the conviction and all available evidence, including the results of the recently conducted DNA tests previously ordered by the Governor to examine additional evidence in the case using the latest, most scientifically reliable forensic testing.

The text of the Governor’s executive order can be found here:

https://www.gov.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/5.28.21-EO-N-06-21.pdf

The California Constitution gives the Governor the authority to grant executive clemency in the form of a pardon, commutation or reprieve. These clemency grants recognize the applicants’ subsequent efforts in self-development or the existence of a medical exigency. They do not forgive or minimize the harm caused.

The Governor regards clemency as an important part of the criminal justice system that can incentivize accountability and rehabilitation, increase public safety by removing counterproductive barriers to successful reentry, correct unjust results in the legal system and address the health needs of incarcerated people with high medical risks.

A pardon may remove counterproductive barriers to employment and public service, restore civic rights and responsibilities and prevent unjust collateral consequences of conviction, such as deportation and permanent family separation. A pardon does not expunge or erase a conviction.

A commutation modifies a sentence, making an incarcerated person eligible for an earlier release or allowing them to go before the Board of Parole Hearings for a hearing at which Parole Commissioners determine whether the individual is suitable for release.

A reprieve allows individuals classified by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation as high medical risk to serve their sentences in appropriate alternative placements in the community consistent with public health and public safety.

The Governor weighs numerous factors in his review of clemency applications, including an applicant’s self-development and conduct since the offense, whether the grant is consistent with public safety and in the interest of justice, and the impact of a grant on the community, including crime victims and survivors.

While in office, Governor Newsom has granted a total of 86 pardons, 92 commutations and 28 reprieves.

The Governor’s Office encourages victims, survivors, and witnesses to register with CDCR’s Office of Victims and Survivors Rights and Services to receive information about an incarcerated person’s status. For general Information about victim services, to learn about victim-offender dialogues, or to register or update a registration confidentially, please visit:

www.cdcr.ca.gov/Victim_Services/ or call 1-877-256-6877 (toll free).

Copies of the gubernatorial clemency certificates announced today can be found here:

https://www.gov.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/5.28.21-Clemency-certs.pdf

Additional information on executive clemency can be found here:

https://www.gov.ca.gov/clemency/

###

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

New Legal Filing in Mumia’s Case

The following statement was issued January 4, 2022, regarding new legal filings by attorneys for Mumia Abu-Jamal.

Campaign to Bring Mumia Home

In her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, Zora Neale Hurston wrote, “There are years that ask questions, and years that answer.”

With continued pressure from below, 2022 will be the year that forces the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office and the Philly Police Department to answer questions about why they framed imprisoned radio journalist and veteran Black Panther Mumia Abu-Jamal. Abu-Jamal’s attorneys have filed a Pennsylvania Post Conviction Relief Act (PCRA) petition focused entirely on the six boxes of case files that were found in a storage room of the DA’s office in late December 2018, after the case being heard before Judge Leon Tucker in the Court of Common Pleas concluded. (tinyurl.com/zkyva464)

The new evidence contained in the boxes is damning, and we need to expose it. It reveals a pattern of misconduct and abuse of authority by the prosecution, including bribery of the state’s two key witnesses, as well as racist exclusion in jury selection—a violation of the landmark Supreme Court decision Batson v. Kentucky. The remedy for each or any of the claims in the petition is a new trial. The court may order a hearing on factual issues raised in the claims. If so, we won’t know for at least a month.

The new evidence includes a handwritten letter penned by Robert Chobert, the prosecution’s star witness. In it, Chobert demands to be paid money promised him by then-Prosecutor Joseph McGill. Other evidence includes notes written by McGill, prominently tracking the race of potential jurors for the purposes of excluding Black people from the jury, and letters and memoranda which reveal that the DA’s office sought to monitor, direct, and intervene in the outstanding prostitution charges against its other key witness Cynthia White.

Mumia Abu-Jamal was framed and convicted 40 years ago in 1982, during one of the most corrupt and racist periods in Philadelphia’s history—the era of cop-turned-mayor Frank Rizzo. It was a moment when the city’s police department, which worked intimately with the DA’s office, routinely engaged in homicidal violence against Black and Latinx detainees, corruption, bribery and tampering with evidence to obtain convictions.

In 1979, under pressure from civil rights activists, the Department of Justice filed an unprecedented lawsuit against the Philadelphia police department and detailed a culture of racist violence, widespread corruption and intimidation that targeted outspoken people like Mumia. Despite concurrent investigations by the FBI and Pennsylvania’s Attorney General and dozens of police convictions, the power and influence of the country’s largest police association, the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) prevailed.

Now, more than 40 years later, we’re still living with the failure to uproot these abuses. Philadelphia continues to fear the powerful FOP, even though it endorses cruelty, racism, and multiple injustices. A culture of fear permeates the “city of brotherly love.”

The contents of these boxes shine light on decades of white supremacy and rampant lawlessness in U.S. courts and prisons. They also hold enormous promise for Mumia’s freedom and challenge us to choose Love, Not PHEAR. (lovenotphear.com/) Stay tuned.

—Workers World, January 4, 2022

https://www.workers.org/2022/01/60925/

Pa. Supreme Court denies widow’s appeal to remove Philly DA from Abu-Jamal case

Abu Jamal was convicted by a jury of first-degree murder of Faulkner in 1982. Over the past four decades, five of his appeals have been quashed.

In 1989, the state’s highest court affirmed Abu-Jamal’s death penalty conviction, and in 2012, he was re-sentenced to life in prison.

Abu-Jamal, 66, remains in prison. He can appeal to the state Supreme Court, or he can file a new appeal.

KYW Newsradio reached out to Abu-Jamal’s attorneys for comment. They shared this statement in full:

“Today, the Superior Court concluded that it lacked jurisdiction to consider issues raised by Mr. Abu-Jamal in prior appeals. Two years ago, the Court of Common Pleas ordered reconsideration of these appeals finding evidence of an appearance of judicial bias when the appeals were first decided. We are disappointed in the Superior Court’s decision and are considering our next steps.

“While this case was pending in the Superior Court, the Commonwealth revealed, for the first time, previously undisclosed evidence related to Mr. Abu-Jamal’s case. That evidence includes a letter indicating that the Commonwealth promised its principal witness against Mr. Abu-Jamal money in connection with his testimony. In today’s decision, the Superior Court made clear that it was not adjudicating the issues raised by this new evidence. This new evidence is critical to any fair determination of the issues raised in this case, and we look forward to presenting it in court.”

https://www.audacy.com/kywnewsradio/news/local/pennsylvania-superior-court-rejects-mumia-abu-jamal-appeal-ron-castille

Questions and comments may be sent to: info@freedomarchives.org

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Sign our petition urging President Biden to grant clemency to Leonard Peltier.

https://www.freeleonardpeltier.com/petition

Thank you!

Email: contact@whoisleonardpeltier.info

Address: 116 W. Osborne Ave. Tampa, Florida 33603

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Resources for Resisting Federal Repression

Since June of 2020, activists have been subjected to an increasingly aggressive crackdown on protests by federal law enforcement. The federal response to the movement for Black Lives has included federal criminal charges for activists, door knocks by federal law enforcement agents, and increased use of federal troops to violently police protests.

The NLG National Office is releasing this resource page for activists who are resisting federal repression. It includes a link to our emergency hotline numbers, as well as our library of Know-Your-Rights materials, our recent federal repression webinar, and a list of some of our recommended resources for activists. We will continue to update this page.

Please visit the NLG Mass Defense Program page for general protest-related legal support hotlines run by NLG chapters.

Emergency Hotlines

If you are contacted by federal law enforcement you should exercise all of your rights. It is always advisable to speak to an attorney before responding to federal authorities.

State and Local Hotlines

If you have been contacted by the FBI or other federal law enforcement, in one of the following areas, you may be able to get help or information from one of these local NLG hotlines for:

- Portland, Oregon: (833) 680-1312

- San Francisco, California: (415) 285-1041 or fbi_hotline@nlgsf.org

- Seattle, Washington: (206) 658-7963

National Hotline

If you are located in an area with no hotline, you can call the following number:

Know Your Rights Materials

The NLG maintains a library of basic Know-Your-Rights guides.

- Know Your Rights During Covid-19

- You Have The Right To Remain Silent: A Know Your Rights Guide for Encounters with Law Enforcement

- Operation Backfire: For Environmental and Animal Rights Activists

WEBINAR: Federal Repression of Activists & Their Lawyers: Legal & Ethical Strategies to Defend Our Movements: presented by NLG-NYC and NLG National Office

We also recommend the following resources:

Center for Constitutional Rights

Civil Liberties Defense Center

- Grand Juries: Slideshow

Grand Jury Resistance Project

Katya Komisaruk

Movement for Black Lives Legal Resources

Tilted Scales Collective

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

The increasing number of deaths adds urgency to questions about when and how agents should engage in high-speed chases as they pursue smugglers and migrants.

By Eileen Sullivan, Jan. 9, 2022

WASHINGTON — Angie Simms had been searching for her 25-year-old son for a week, filing a missing persons report and calling anyone who might have seen him, when the call came last August. Her son, Erik A. Molix, was in a hospital in El Paso, Texas, where he was strapped to his bed, on a ventilator and in a medically induced coma.

Mr. Molix had suffered head trauma after the S.U.V. he was driving with nine undocumented immigrants inside rolled over near Las Cruces, N.M., while Border Patrol agents pursued him at speeds of up to 73 miles per hour. He died Aug. 15, nearly two weeks after the crash; even by then, no one from the Border Patrol or any other law enforcement or government agency had contacted his family.

The number of migrants crossing the border illegally has soared, with the Border Patrol recording the highest number of encounters in more than six decades in the fiscal year that ended Sept. 30. With the surge has come an increase in deaths and injuries from high-speed chases by the Border Patrol, a trend that Customs and Border Protection, which oversees the Border Patrol, attributes to a rise in brazen smugglers trying to flee its agents.

From 2010 to 2019, high-speed chases by the Border Patrol resulted in an average of 3.5 deaths a year, according to the American Civil Liberties Union. In 2020, there were 14 such deaths; in 2021, there were 21, the last on Christmas.

The agency recorded more than 700 “use of force” incidents on or near the southern border in the last fiscal year. Customs and Border Protection does not disclose how many of those ended in death, or how many high-speed chases take place each year.

Crossing the border without documentation or helping people do so is full of risk regardless of the circumstances, and stopping such crossings — and the criminal activity of smugglers — is central to the Border Patrol’s job. But the rising deaths raise questions about how far the agency should go with pursuits of smugglers and migrants, and when and how agents should engage in high-speed chases.

Customs and Border Protection has yet to provide Ms. Simms, a fifth-grade teacher in El Paso, with an explanation of what happened to her son. She saw a news release it issued two weeks after the crash; officials say it is not the agency’s responsibility to explain. She said she understood that officials suspected her son was involved in illegal activity, transporting undocumented immigrants.

“But that doesn’t mean you have to die for it,” she said.

Customs and Border Protection, which is part of the Department of Homeland Security, has a policy stating that agents and officers can conduct high-speed chases when they determine “that the law enforcement benefit and need for emergency driving outweighs the immediate and potential danger created by such emergency driving.” The A.C.L.U. argues that the policy, which the agency publicly disclosed for the first time last month, gives agents too much discretion in determining the risk to public safety.

In a statement to The New York Times, Alejandro N. Mayorkas, the secretary of homeland security, said that while “C.B.P. agents and officers risk their lives every day to keep our communities safe,” the Homeland Security Department “owes the public the fair, objective and transparent investigation of use-of-force incidents to ensure that our highest standards are maintained and enforced.”

But previously unreported documents and details of the crash that killed Mr. Molix shed light on what critics say is a troubling pattern in which the Border Patrol keeps its operations opaque, despite the rising human toll of aggressive enforcement actions.

A high-speed chase

Early on Aug. 3, a Border Patrol agent saw an S.U.V. traveling slowly just north of Las Cruces with what appeared to be a heavy load, according to a report from the New Mexico State Police.

When the S.U.V. swerved to avoid a Border Patrol checkpoint, on a lonely stretch of road about 70 miles north of the border, the agent and a colleague in a separate car started chasing it. They pursued it for about a mile before one of them “clipped the vehicle and it rolled,” according to local emergency dispatch records. Eight of the 10 passengers — migrants from Ecuador, Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador — were ejected. An Ecuadorean man later died.

The New Mexico State Police was among the agencies that responded to the crash. Body camera footage from a state police officer captured one of the Border Patrol agents saying: “Our critical incident team is coming out. They’ll do all the crime scene stuff — well, not crime scene, but critical incident scene.”

The agent said that he and his colleague would give statements to the team, which it would share with the police.

Critical incident teams are rarely mentioned by Customs and Border Protection or the Border Patrol. There is no public description of the scope of their authority.

Luis Miranda, a spokesman for Customs and Border Protection, said the teams consist of “highly trained evidence collection experts” who gather and process evidence for investigations, including inquiries into human smuggling and drug trafficking. He also said the teams assist in investigations conducted by the agency’s Office of Professional Responsibility, which looks into claims of agent misconduct and is akin to internal affairs divisions of police departments.

Another Homeland Security official, who was authorized to speak to a reporter about the teams on the condition that the official’s name was not used, confirmed another role they have: collecting evidence that could be used to protect a Border Patrol agent and “help deal with potential liability issues,” such as a future civil suit.

Andrea Guerrero, who leads a community group in San Diego and has spent the past year looking into critical incident teams and their work, said it was “an outright conflict of interest” for the division charged with investigating possible Border Patrol misconduct to rely on assistance from Border Patrol agents on the teams. She has called on Congress to investigate and filed a complaint with the Homeland Security Department.

Customs and Border Protection officials said the El Paso sector’s critical incident team merely helped with measurements for a reconstruction of the crash outside Las Cruces; the Office of Professional Responsibility, they said, is investigating the incident. Yet a member of the El Paso critical incident team reached out to the state police in the days after the crash seeking the department’s full report for its own Border Patrol administrative review, according to an email released by the state police.

Few public answers

Border Patrol encounters that result in injury or death can be investigated by multiple entities: the F.B.I., state and local law enforcement, the Homeland Security Department’s inspector general or Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, and the Office of Professional Responsibility, where most such incidents land for review. But the findings on individual cases are rarely disclosed; such investigations tend to yield few public details beyond total numbers, which show only a fraction result in some type of discipline.

An incident in 2010 drew international attention and calls for change. A 42-year-old Mexican caught entering the country illegally died after he was hogtied, beaten and shocked with a Taser by Border Patrol agents. The Justice Department declined to investigate, but more than a decade later, the case will be heard this year by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights court — an apparent first for a person killed by a U.S. law enforcement officer.

After the man’s death, the Obama administration made changes to address a litany of excessive force complaints against Border Patrol agents and bring more transparency and accountability to Customs and Border Protection. An external review of Customs and Border Protection’s use-of-force policy recommended defining the authority and role of critical incident teams.

Chuck Wexler, the executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum, a nonprofit policy and research organization that conducted the external review, said that if his organization had known more at the time about the team’s purpose, it would have “raised red flags.” But instead of explaining what the teams did, the agency cut any mention of them out of the use-of-force policy.

In another case brimming with questions, a Border Patrol agent in Nogales, Ariz., shot an undocumented woman who was unarmed, Marisol García Alcántara, in the head last June while she sat in the back seat of a car. A Nogales Police Department report noted that the Border Patrol supervisor at the scene refused to provide information to officers about what had happened in the lead-up to the crash. The report also noted that a critical incident team arrived on the scene.

Ms. García Alcántara, a mother of three, was taken to a hospital in Tucson, where doctors removed most of the bullet from her head. Three days later, she was discharged and sent to an Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention center, where she remained for 22 days before being deported to Mexico. She said she was never interviewed by law enforcement; a Customs and Border Protection official said the F.B.I. was investigating.

Representative Raúl M. Grijalva of Arizona, a Democrat who represents Tucson, said Ms. García Alcántara’s case raised questions about the “illegal practice” of the critical incident teams which, he said, have no legal authorization and escape the oversight of Congress. Other lawmakers, too, are demanding answers.

Answers have not come easily for Ms. Simms, who had overheard whispers about a car crash and the Border Patrol while she sat by her son in the hospital.

Three days after Mr. Molix died, Ms. Simms heard from Customs and Border Protection for the first time. “We wanted to give our condolences to you and your family,” an investigator with the Office of Professional Responsibility texted. “We also needed to see if we could meet you to sign a medical release form for Mr. Erik Anthony Molix.”

An A.C.L.U. lawyer, Shaw Drake, pieced together the details of the crash using police reports, body camera footage and records of emergency dispatch calls that he obtained through public records requests.

Details of the investigation into what Mr. Molix was doing that day remain under wraps. Customs and Border Protection said that because Mr. Molix was not in Border Patrol custody after he was admitted to the hospital, it was not obliged to notify his family about his injuries.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

By Craig Spencer, Jan. 10, 2022

Dr. Spencer is an emergency room doctor in New York City.

As the Omicron tsunami crashes ashore in New York City, the comforting news that this variant generally causes milder disease overlooks the unfolding tragedy happening on the front lines.

As an emergency room doctor fighting this new surge, I am grateful that vaccines and a potentially less lethal variant have meant that fewer of my patients today need life support than they did at the start of the pandemic. In March 2020, nurses and doctors rushed between patients, endlessly trying to stabilize one before another crashed. Many of my patients needed supplemental oxygen and the sickest needed to be put on ventilators. Many never came off them. Our intensive care units filled beyond capacity, and yet patients kept coming.

Thankfully, this wave is not like that. I haven’t needed to put any Covid-19 patients on a ventilator so far. And the majority of patients haven’t needed supplemental oxygen, either.

We also have good treatment tools: cheap, widely available medications like steroids have proved to be lifesavers for Covid-19 patients. We now know that administering oxygen at high flow rates through the nose substantially improves patient outcomes. Although currently in very short supply, oral antivirals are highly effective at reducing Covid hospitalizations. The greatest relief has come from the vaccines, which keep people out of the hospital regardless of the variant.

Yet these tools are still not enough to slow the rapid influx of patients we’re now seeing from Omicron, and the situation is bleak for health workers and hospitals.

In New York City, hospitalizations have tripled in the past few weeks alone. New Jersey is seeing its highest number of hospitalizations of the whole pandemic. In all, nearly every state and territory is seeing Covid admissions on the rise.

For most people — especially the vaccinated — Omicron presents as a sore throat or a mild inconvenience. But among the many patients in our hospital, the situation is serious. On a recent shift, I still saw “classic” Covid-19 patients, short of breath and needing oxygen. All of them were unvaccinated. I also saw elderly patients for whom Covid rendered them too weak to get out of bed. I treated people with diabetes in whom the virus caused serious and potentially fatal complications.

And even though nearly all of my patients are experiencing milder illness compared with March 2020, they still take up the same amount of space in a hospital bed. Right now, all patients with the coronavirus require isolation, so they don’t infect other patients, and the laborious use of personal protective equipment by health workers. Yes, there’s a fraction of patients who are incidentally found to have the virus — for example, a person needing an appendix removed who tests positive on screening. But entering the hospital with the virus versus for the virus isn’t a relevant distinction if the hospital doesn’t have the beds or providers needed to care for its patients.

And even though nearly all of my patients are experiencing milder illness compared with March 2020, they still take up the same amount of space in a hospital bed. Right now, all patients with the coronavirus require isolation, so they don’t infect other patients, and the laborious use of personal protective equipment by health workers. Yes, there’s a fraction of patients who are incidentally found to have the virus — for example, a person needing an appendix removed who tests positive on screening. But entering the hospital with the virus versus for the virus isn’t a relevant distinction if the hospital doesn’t have the beds or providers needed to care for its patients.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

After a deadly high-rise blaze in 2017, countless instances of unsafe building practices came to light. The latest plan to address them expands who will be covered.

By Megan Specia, Published Jan. 10, 2022, Updated Jan. 11, 2022

LONDON — Britain’s housing secretary announced plans on Monday to overhaul the government’s approach to building safety issues across England, saying the financial burden should fall on developers to address lapses in fire safety in hundreds of apartment blocks.

The plan also includes funding to remove flammable material from mid-rise buildings, which had been neglected in a previous plan, and could free homeowners from burdensome costs.

In the nearly five years since a devastating fire killed 72 people as it tore through Grenfell Tower, a high-rise residential building in London that was encased in a flammable exterior covering, countless other instances of unsafe building practices have come to light in England. Apartment owners found themselves stuck in unsafe homes that they cannot sell, or facing excessive bills to fix dangerous fire safety lapses that include the use of similar exterior materials as those used on Grenfell, known as cladding.

“Four and a half years on from the tragedy of Grenfell, it is long past time that we fix this crisis,” Michael Gove, Britain’s housing secretary, told Parliament on Monday. “And through the measures that I’ve set out today, we will seek redress for past wrongs and secure funds from developers and from construction product manufactures and we will protect leaseholders today and fix the system for the future.”

Most private apartments in England are sold as long-term leases, with the owner known as the “leaseholder,” and the buildings themselves are owned by a “freeholder,” often an investment group. Residents in buildings with fire safety issues have struggled to hold developers accountable for the use of dangerous materials.

The widespread nature of the issues is rooted in decades of deregulation in England, which led to lenient building rules that saw some developers prioritize cutting costs over safety. Industry experts have estimated that the remediation costs for cladding issues across England could amount to more than 50 billion pounds, $67 billion, far higher than the pledges made by the government.

Mr. Gove took over the role of housing secretary in September, inheriting the housing crisis from his predecessor Robert Jenrick, whose plans to address the issue with billions of dollars of additional funding had been widely criticized for not budgeting enough money or addressing the scope of the issue, even within his own Conservative Party. The earlier plans did not account for lower-rise buildings that have the same safety lapses.

Crucially, Mr. Gove said developers could be held legally accountable if they do not contribute to the cost of making buildings safe. A letter written by Mr. Gove to building developers on Monday offered a “window of opportunity” from now until March to agree on a settlement to address the cost and proposed discussions between the government, developers, leaseholders and the bereaved families and survivors of the Grenfell Tower fire.

“We will give them the chance to do the right thing,” he said of the development companies. “I hope they take it. If they do not, and if necessary, we will impose a solution upon them in law.”

Opposition lawmakers, however, called into question whether the new promises will spur real change. Lisa Nandy, the opposition Labour lawmaker responsible for housing, called the announcement a “welcome shift in tone” and said that she hoped the new measures would prove fruitful.

“But the harder I look at this, the less it stands up,” she added. “We were promised justice and we were promised changes to finally do right by the victims of this scandal, but that takes more than more promises, it takes a plan.”

While many leaseholders are hopeful that the announcement could alleviate both the financial burden and psychological burden of living in unsafe buildings, many have pushed for a legally binding plan for ensuring developers shoulder these costs.

“I think most leaseholders, myself included, are kind of cautiously optimistic,” said Sophie Bichener, 29, who owns an apartment in Stevenage, about 30 miles north of London. “But, I think there are lots of details that we still don’t know.”

Ms. Bichener has been among a number of leaseholders who met with Mr. Gove in recent weeks, and she said she came out of a meeting with him just hours before the announcement feeling positive. She noted that the announcement definitely marks “a new tone from the government about the building safety crisis,” but it does not alleviate all of her concerns.

Two years ago, fire safety surveys determined that the building she lives in is unsafe and would need to be fixed. Not only is it wrapped in a potentially flammable material, but there are also a variety of other concerns. A cost of 208,000 pounds, around $280,000, was passed along to all leaseholders in her building, and they have also experienced increases in their insurance and fronted the costs for fire safety patrols.

About 30 percent of the remediation costs to ensure Ms. Bichener’s building is fire safe are for defects that have nothing to do with cladding — like potentially flammable insulation, timber balconies and more — which were not covered in this new announcement. She feels like she has been left in limbo and said the toll on her mental health has been immense.

“They are still going to be life-changing sums of money for leaseholders to fork out for themselves, even though a lot of those things were against the regulations at the time they were built,” she said.

End Our Cladding Scandal, a leaseholder group that advocates for a solution to the crisis, said it welcomed the announcement but said there were still gaps, and it criticized the housing secretary for a lack of government accountability.

“There must be a recognition, too, of the part that successive governments have played in this wider scandal,” the group said in a statement. “Homeowners may have been failed by the construction sector and by cladding manufacturers — but they have also been failed by the ministers and officials meant to regulate those industries.”

Deepa Mistry, the chief of BuildingSafetyCrisis.org, owns an apartment in a London building where fire safety hazards were identified.

She has been advocating for an amendment to building safety legislation currently making its way through Parliament that would allow the government to pursue developers for costs to fix homes, and which advocates believe will protect buyers and restore trust by forcing wrongdoers to pay.

Ms. Mistry and her young family have felt trapped by the crisis, unable to sell their apartment and move on. She said that while Mr. Gove’s statement reflected some positive developments, she believed the solution must include global fire safety reforms, pointing to a deadly fire in the Bronx on Sunday as just the latest example of how better protections are needed in high-rise buildings.

Ms. Mistry hopes that the cladding crisis leads to a fundamental shift in fire safety practices and makes it “so that the innocent aren’t left with the burden — either paying through their pocket or through their lives,” she said. “It’s just not right.”

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Two days after the fire, the city released a partial list of the deceased.

By Jazmine Hughes and Sean Piccoli, Jan. 11, 2022

Worshipers at a mosque in the Bronx sat shoeless in small groups along the edge of the carpeted floor. Services were still almost an hour away, but as coffee containers arrived and cups were poured, the imam tried to comfort people caught between anguish and grief.

They were all relatives of people still missing more than 24 hours after a fatal fire in a Bronx apartment building that killed 17, including eight children. As many as 12 members of the Masjid-Ur-Rahmah mosque were believed to have died in the fire, the imam, Musa Kabba, said.

“We give them the pictures. We give them the names. We give them the phone numbers. We’re still waiting for them to identify them,” Mr. Kabba said.

On Tuesday night, the city released a partial list of the deceased. The chaos of the rescue and the striking number of victims complicated the identification process.

On Sunday, more than 60 fire victims initially went to four different hospitals in the Bronx. Seventeen of them died within hours, all of the deaths attributed to severe smoke inhalation. About a dozen critically ill patients were stabilized at local hospitals and later transferred to facilities with specialized burn units in Manhattan, Westchester County and other parts of the Bronx.

Many survivors were also treated for severe smoke inhalation, which can cause people to become unconscious from lack of oxygen. Not everyone carried identification, and some residents shared similar names to other family members. Multiple members of a single family were close in age, also adding to confusion.

Features like tattoos, body jewelry, nail art and scars were used to piece together identities of the deceased, the medical examiner’s office said.

The office has used DNA matching to confirm identities by obtaining DNA from relatives and notifying immediate family members after a match has been made, City Hall officials said. The deliberate process has contributed to a lag in releasing the names of the deceased, officials said.

Shivonne Hutson, the city’s executive director of forensic investigations, said forensic examiners were also mindful of language and religious differences. Many of the building’s residents had relocated to the Bronx from Gambia, a small West African country with a largely Muslim population.

“Observances — these things extend not just in life, but they carry on into death,” Ms. Hutson said.

Age, too, was a complicating factor: without any identification or little previous medical history, the children posed a particular challenge. “Kids don’t have all the records,” like fingerprints or dental records, that adults may have, Ms. Hutson said.

After the flames subsided and the fatal smoke dissipated, a new horror crept in: Other residents, family members and friends were left unsure about the status of loved ones. Hours rolled by, and many people across New York and Gambia spent hours in excruciating limbo, unsure who was alive or dead.

Some families called every hospital in the area, searching for missing relatives. Others visited on foot, desperate for answers.

Aid workers at Monroe College, which is serving as a temporary emergency response center, have been relying on an unofficial list of the dead, injured, missing and displaced, compiled by a local community board member. He has tried to write down the names, contact information and needs of every person who shows up at the college, in an ad hoc intake list.

Gathering information is hard, in part because of language barriers, said Abdoulaye Cisse, a community outreach worker for CAIR-NY, a group that advocates for Muslims. Some residents speak English, but others speak only various combinations of French and the many languages of West Africa.

Fears of immigration authorities linger among some undocumented residents. And some families, he said, are deeply private or are in shock and not ready to talk about their situation.

Dustin Jones watched television footage of the Bronx fire from his apartment in the Chelsea area of Manhattan, frantically calling a friend who he thought lived in the building. Luckily, he was mistaken — she lived a few blocks away — but his relief didn’t last long.

He quickly learned he knew two residents of the building: Ramel Thompson, 44, and Dorel Anderson, 38, a couple. The three had met each other through a tight-knit disability community: Mr. Thompson and Ms. Anderson both have cerebral palsy, and Mr. Jones is an advocate of disability rights.

After failing to contact the couple, Mr. Jones and about 100 others, many of them relatives of the couple and members of the disabled community, began a 24-hour search for them, much of it online.

He also knew the couple lived on the 13th floor, and was particularly worried about Ms. Anderson, who uses a wheelchair.

Mr. Jones said he never considered contacting the city for assistance. Instead, he amplified the missing couple on social media, reached out to his media contacts and called friends for information, including a firefighter who had been on the scene. “We live in the age of social media, and I’ve seen miracles happen,” Mr. Jones said.

A relative eventually found the couple at Westchester Medical Center, in Valhalla, N.Y., on Monday, where they were transferred to an advanced burn unit. Ms. Anderson and Mr. Thompson were still being treated; Ms. Anderson’s wheelchair was missing.

Breanna Elleston, 27, said she heard her best friend Sera Janneh, 27, was missing on Sunday. Ms. Elleston assumed that Ms. Janneh was in the hospital, unidentified. She called a few close friends and asked them to reach out to her. Their calls went straight to voice mail.

So Ms. Elleston made an Instagram post about her friend, and asked followers to share it, to “see if they knew anybody that worked in nearby hospitals, if they see her face, they could match it up with a picture.” There was still no luck.

Undeterred, Ms. Elleston and some friends planned to put up pictures around the Bronx. When she informed Ms. Janneh’s family of the plan, they told her Ms. Janneh had died.

Mohamed Kamra, too, was working a shift as a taxi driver when he learned that his family was caught in the blaze.

He and a relative frantically tried to locate their entire family. Soon, they found 6-year-old Jabu, 3-year-old Abubakary and baby Ceesay, not yet a year old. But it took hours for Mr. Kamra to locate his wife, Fatoumatia, or his eldest daughter, 8-year-old Mariam.

Christina Kharem, a teacher and special education coach at Mariam’s school, spent her day on the phone with her principal calling hospitals around the city, trying to locate Mariam and her mother, while Mr. Kamra searched in person.

He found Mariam and Fatoumatia by Sunday evening. Each family member was in medically induced comas and on ventilators.

With Mr. Kamra’s permission, Ms. Kharem created an online fund-raiser for the Kamra family around 3 a.m. Monday, asking for donations of both money and supplies. They got their first donation before dawn.

By Monday afternoon, Mr. Kamra had visited four of his hospitalized family members and was on his way to see a fifth.

Relieved that he tracked down his family, he remained optimistic on Monday night that they would recover. “For me, right now, it’s no bad memory yet,” he said.

But for some, hope diminished as the hours went by without news.

Yusupha Jawara told CBS New York that he called 311 more than 40 times trying to learn the fate of his younger brother and sister-in-law, who lived in the building, a block from him.

“We tried all they said,” Mr. Jawara, 47, said in an interview with The New York Times. “Nothing is working for us now.”

He said he understood there were procedures to be followed. “But we need a closure on this to know whether they are alive or dead,” Mr. Jawara said. “That’s all we need. We are not asking for the bodies to be given to us right now. He’s alive or he’s dead. That’s all we need to know.”

At about 4:30 p.m. on Monday, Mr. Jawara texted a reporter that he had received word: His brother and sister-in-law perished in the fire.

Sharon Otterman, Sarah Maslin Nir, Anne Barnard, Lola Fadulu and Jeffery C. Mays contributed reporting. Susan C. Beachy contributed research.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

By Vanessa Veselka, Photographs by Clayton Cotterell, Jan. 14, 2022

Ms. Veselka is a writer and former union organizer.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/14/opinion/unions-oregon-assisted-living.html

The Rawlin

Last winter, workers at a memory care facility in western Oregon decided they were done watching the residents suffer. Conditions at the Rawlin at Riverbend, a 72-bed home in Springfield, were horrific because of critically low staffing and a lack of training. Elderly residents screamed from their rooms for assistance, and workers had to make the kinds of decisions that people are forced to make in war: Do you take precious time to do emergency wound care, even though you aren’t quite sure how, knowing that it means other residents might sit in their own feces for hours or trip and fall in the hallways? Do you stop to feed a resident who has trouble swallowing, knowing that others may not be fed if you do?

According to workers, Onelife, the company that operated the Rawlin, did not provide enough staff to properly care for the dozens of residents with dementia and other serious health problems. Around 20 residents died in about two months, from mid-November 2020 to mid-January 2021, only six of them from Covid. Many of the other deaths, caregivers believe, could have been prevented with better treatment.

Families of the residents, who often serve as a second pair of eyes on an industry prone to neglect, were mostly unable to enter the Rawlin for months because of Covid, so the added pressure to staff the home properly disappeared. After the facility lost its on-site registered nurse, Onelife temporarily replaced her with a regional nurse who visited the premises a few days a week and otherwise had to be reached by phone.

Experienced staff members watched their colleagues throw in the towel and walk out, wondering if they should do the same. Jenn Gregory, who had been at the Rawlin for more than two years, was one of the few more seasoned workers who stayed, trying to hold everyone together. She was making $12.40 an hour, just above Oregon’s minimum wage at the time, alongside new hires making $13 and $14. They were mostly young — some fresh out of high school with no experience.

At one point, Ms. Gregory, who had recently recovered from Covid and had not yet regained her sense of smell, entered a room to find an elderly woman with large bedsores that had become infected. One of them was the size of a softball and deep enough to expose the bone. Ms. Gregory called a co-worker, 18-year-old Eric Holmes, into the room to help. When she left to continue rounds, the stench was so unbearable that the next resident she attended, a veteran, kicked her out of his room because she “smelled like Vietnam.”

(In an email to The New York Times, Zack Falk, the chief executive of Onelife, disputed the description of the woman’s wounds, writing that he believes she had arrived from the hospital with bedsores. He also challenged his former employees’ recollections of the circumstances surrounding the deaths of many of the residents. According to Mr. Falk, all workers received proper training, staffing never fell below state-mandated requirements and the death toll did not differ significantly from a similar time period in the winter of 2019.)

Caregivers at the Rawlin formed a traumatized family, which grew closer with each new death. They called the state. They pleaded with management for more workers and higher wages to retain them — at least something more than what they’d earn at a fast-food restaurant. Not knowing what else to do, they contacted the local union.

I had been with the union for a year and a half when we got the call about the Rawlin. As an organizer with Local 503 of the Service Employees International Union, I represented long-term-care workers across the state of Oregon, and I knew that the nursing home industry had been in disarray even before the pandemic.

When Covid hit, workers in some nursing homes had to walk around in garbage bags and use bandannas for masks long after the hospitals got proper personal protective gear. And in my experience, whatever is bad in standard nursing homes tends to be far worse in memory care. So I wasn’t surprised to get a call from memory care workers. What would be a surprise is how dedicated they would become to forming a union.

To form a union, employees are supposed to gather signatures from at least 30 percent of eligible workers and submit them to the National Labor Relations Board as a “showing of interest.” The labor board then sets up an election, which is decided by a simple majority. I’ve never seen workers win if they follow these instructions. If the workers have an outright majority on union cards, they can also ask the employer to voluntarily recognize the union. I’ve only rarely seen this happen.

Legally, private employers are not allowed to interfere with the right to organize. They cannot bribe, threaten, retaliate, surveil, give the appearance of surveilling, or fire workers for organizing. My experience is that many employers do all these things. I was taught that to win a “boss fight,” union supporters need to organize underground until at least 70 percent of employees have signed union cards so that they can withstand a 15 percent to 20 percent drop in participation when the employer counter-campaign hits.

The crucial period is the time between filing for an election and voting. During the Trump administration, the labor board issued a rule that allowed employers to delay elections through legal maneuvers, and also permitted them to file postelection challenges, which can prevent workers from moving into the bargaining phase at a reasonable pace. Time is a white-collar weapon. People with resources can easily outwait people with none. The longer it takes to get to an election, the less chance workers have of winning their union.

At a place like the Rawlin, which had a small staff with high turnover, workers would never make it through that process. If the employer’s anti-union tactics didn’t get them, attrition likely would. Even if they did manage to eke out a victory, they would need to bargain a contract, giving employers another round of ways to stall. With a hostile employer, those negotiations could take a year, and workers might still have to strike to win anything.

Given the situation, we told workers the truth: If they wanted a union, and truly could not wait for change, they would have to get an undeniable supermajority on union cards and strike until the employer voluntarily recognized the union.

This is the route they chose.

By our count, 85 percent of the eligible workers signed union cards within a week, and they approached management to demand recognition of their union. They gave management 72 hours to respond. We uploaded videos to social media showing workers talking about the union drive, which meant that the campaign was immediately public. After the Rawlin said it would not voluntarily recognize the union, workers delivered notice of their intent to strike.

A strike for recognition is a radical act. In all my years in labor, I had never been involved with one. My introduction to organizing had come more than two decades earlier, when I took a job at an Amazon warehouse in Seattle, hoping to unionize the work force.

Back then, in 1999, the company was poised to become the Walmart of the internet, opening distribution centers across the country. Already, Amazon appeared to be vehemently anti-union. Company policies made it difficult for people to congregate or talk to one another much. When rumors spread that the Seattle warehouse was organizing, management started searching us for fliers and other pro-union materials.

Despite the failure of that drive, my desire to organize remained. I had seen in unions what I had not seen in other kinds of activism: power. The ability to shut down a business seemed like the only check on the unbridled dash for corporate profit. So I took a job at an S.E.I.U. local, 1199NW, for health care workers in Washington, where I learned the fundamentals of organizing: Tell workers it’s their union and then behave that way; workers know the risks; never lie.

As we won union elections at hospitals around the state, I saw that organizing could lead to far more than the right to bargain collectively for wages and benefits. It can be transformative. People decide to go back to school. They finally make appointments to see an eye doctor instead of relying on “readers” from the grocery store. They leave abusive partners. In short, they begin to imagine a better future, one that includes them. I loved witnessing that.

But I also felt we were fighting an uphill battle. Union membership had been declining for decades. The labor board’s 1949 “Joy Silk doctrine,” the fair standard under which many members of the Greatest Generation unionized, held that when workers present union cards and request recognition, employers must recognize the union and begin the bargaining phase unless they have a “good faith doubt” in the union’s claim of a majority, making it unlawful to insist on an election simply to buy time to undermine the campaign. The Joy Silk standard was abandoned around 1970, and rules became more favorable to employers.

The assault on workers’ rights continued under Ronald Reagan then George H.W. Bush then Bill Clinton. With the rise of Fox News and Rush Limbaugh, I saw workers internalize anti-union sentiment. When most people think of the George W. Bush presidency, they think of the Sept. 11 attacks, or the Iraq war, or Hurricane Katrina. What I remember was the assault on labor. Overtime rights were stripped, federal safety standards were rolled back, and many government employees lost important whistle-blower protections.

Over time, the hard-won victories of health care workers here and there began to look to me like skirmishes on the edge of an empire. These fights cost workers so much and the employer so little. Corporations can pour money into union-busting consultants who are trained to pit people against one another. I’ve seen email addresses of white workers used to send out racial slurs, and schedules suddenly shifted to hobble single mothers. In the words of one reformed union buster, the job was to break the collective spirit “to be sure it would never blossom into a united work force.”

I waited to see if the Onelife would hire a union buster. Onelife was founded by a former doctor named Greg Falk and his son, Zack. In 2016, Greg Falk agreed to give up his medical license after the Oregon Medical Board found that he had engaged in “unprofessional or dishonorable conduct” and “gross or repeated negligence.” (Zack Falk said that his father “chose to retire rather than engage in a lengthy and expensive defense of his practice.”) In 2017, Dr. Falk opened the Rawlin with Zack, who became the chief executive of Onelife.

I knew the Falks had money — Greg Falk and his wife had purchased a $6.25 million house the previous year — but Onelife was a relatively small operation, with four facilities in Oregon, all of which receive Medicaid funding. I had thought Onelife might be unwilling to spend big on a union buster. I was wrong.

Soon enough, a white catering tent popped up in the Rawlin parking lot. Inside the tent was a man who had come to “educate” workers about unions. He was sent by a national consulting firm renowned for its anti-union zeal. A form filed by the firm later showed that Onelife paid the company $3,500 a day plus expenses. The tent, free food for workers, hotel and rental car for the consultant could have added $1,000 more a day.

A union buster’s pitch is almost always the same: Unions are corrupt and will take your money. Nothing will change anyway. Unions were important back in the day, but we don’t need them now. Often a worker is trotted out to describe a bad experience they had with a union elsewhere. Sometimes there’s an email from the company saying an anti-union employee had their tires slashed, and that they respect employees’ right to organize but can’t condone violence, which is occasionally followed by a tearful female manager claiming to have received death threats at her home.

Over the last several years, our understanding of power imbalances in the workplace around sexual harassment has grown enormously; our understanding of such imbalances when it comes to organizing has not. In higher-wage sectors, where career opportunities hinge on recommendations, workers are held hostage through their reputations. In lower-wage industries, simple things like a schedule change can upend the life of an employee, particularly a single parent dependent on child care. Free food provided by union busters may not seem like much of an inducement to vote down a union, but for workers who live in poverty like some of those at the Rawlin, food insecurity was real.

As the strike approached, the influence of the union buster began to show. The first slip we saw was on days when most of the single moms worked. The next slips came among their relatives or closest friends. We lost just under 20 percent of our support in five days. Our campaign was in free fall.

With support hovering at around 60 percent, we met with workers to decide if we should move forward with the strike. We gathered in the parking lot of an empty pizza place by the Willamette River. As caregivers made picket signs. I moved off to the side to talk privately with Summer Trosko, a medical technician in her 40s with strong hands, thick black hair and olive skin.

There are always multiple leaders in a union drive, but often there emerges a leader of leaders. Ms. Trosko was that person. She had a moral core of quiet fury over what was happening to her residents paired with a deep compassion for her co-workers. I told her I didn’t think we could hold it together and strike with a majority. She thought we could. “When you step out and do the right thing,” she said, “the universe has your back.”

I’m always nervous the night before an action. All I want to do is eat lasagna and pace. In the days leading up to the strike, we’d continued to release videos that the workers had made about their experiences, but the next day we would be in a very different media environment. The first group that had reached out to support the strike was the local chapter of the Socialist Rifle Association, a left-wing pro-gun group. We thanked them profusely and begged them not to wear anything to the picket line that revealed their affiliation. Not only did we not need signs reading, “The Socialist Rifle Association Supports Memory Care Workers” but we did not need the Proud Boys who, in Oregon, would almost certainly follow.

Health care strikes are not like other strikes. Because of the nature of the work, caregivers, who are almost all women and often people of color, cannot just walk off the job. They must give 10 days of notice so that the employer has time to hire replacement workers from staffing agencies, frequently paying them double the wages of the employees they are replacing.

One great disadvantage for the strikers was how easily they could be replaced. Assisted living and residential care is an underregulated industry: Oregon requires no certification for caregivers in memory care facilities. Med techs like Ms. Trosko can be hired off the street with zero experience on a Monday and pass out Schedule II drugs like OxyContin and morphine by Thursday. And even if the Falks paid double for replacements for strikers, that meant only around an extra $12 to 16 an hour for roughly two dozen workers.

The morning the strike began, a picket line formed in front of the Rawlin. At the last moment, Local 503 members had voted to support the strikers with picket pay at $100 a day, a figure that still amounted to a loss for many of the workers. People moved in a loose circle, made looser by social distancing. By midmorning, activists, church members and workers from other unions joined the picket line.

All day long, the striking workers cleared the driveway to make way for their replacements, many of whom wore union stickers as a show of support. Some members of the original staff also drove through, taking fliers and apologizing, unable to look the strikers in the eye. Zack Falk rolled back and forth through the picket line in a glossy sports car. A man who worked for Onelife appeared to videotape the picket line — just one of many actions taken by the company that workers believed were threatening. Employees reported being told they would not be able to return to their jobs if they went on strike, and two workers said they were cornered by management before the strike. (Mr. Falk denies these allegations.)

But protections around the right to organize are largely nonexistent. It’s extremely difficult to meet the labor board’s criteria for a ruling against an employer. In general, a complainant must first prove that managers knew that he or she was organizing and that their intent was to retaliate. As police-reform activists know, intent is very hard to prove. Even if you provide sufficient evidence in the form of a miraculous damning email, the process is slow and the remedies generally toothless — certainly not strong enough to stop an employer from doing it again.

We filed two charges against Onelife alleging coercion, among other things, but we did not expect either to stick and eventually withdrew them. Had they been affirmed, they may have resulted only in notices being posted inside the Rawlin.

On the fourth night of the strike, picketers organized a candlelight vigil for the residents who had died. Candlelight vigils sometimes irk me because so often that’s how women are forced to perform sainthood to wring change out of a public terrified of their anger. Put simply, I have never seen the union that represents street maintenance workers hold a candlelight vigil over traffic deaths. In this case, though, the vigil was an act in total earnest. The caregivers, who had been so close to the residents, in some cases closer than their families, hadn’t really had a place to come together and grieve.

People gathered on the wet grass, holding umbrellas. Under a pop-up tent were candles with the room numbers of the deceased written on them. Caregivers shared what memories they could, but since medical privacy rules prohibit the use of names and details, much of it was coded, a language only intelligible to the workers. In tones that rose and fell, they said, “That one was my best friend”; “he was a wonderful man”; “she was a feisty little thing”; “they are our family.”

Ms. Trosko told the crowd the workers would strike for 10 more days. I have often wondered what makes people fight when they suspect they aren’t going to win. Here, I knew. It was for the residents.

I wish I could say that the Rawlin workers got their union, but they didn’t. The strike lasted for 14 days, after which many of the workers who were on strike decided to quit together. About twelve employees marched over to the facility and handed their resignation letters in person. Ms. Trosko said it felt great.

For reasons I don’t fully understand, the things that usually mark a loss after campaigns like these didn’t happen. All the things that come with winning did. One worker got her driver’s license, another left an abusive relationship, and at least two more went back to school. Elizabeth Roby, who had moved from Panda Express into the care industry, decided to train to become a certified nursing assistant. Ms. Gregory refused to work for under $15 at her next job, and later joined Mr. Holmes at the facility where he landed. They are now making $16 an hour.

Ms. Trosko and another med tech, Hermes Ochoa, traveled around the state talking to lawmakers and their constituents about the need for more transparency and oversight in the memory care industry. Thanks in part to their efforts and the media attention drawn by the strike, the Rawlin had to respond to queries about allegations of neglect and inadequate staffing from the Oregon Department of Human Services and the county’s Adult Protective Services unit, which are both unionized as a part of SEIU 503, the union organizing the Rawlin. (Mr. Falk said Onelife was inundated with an unprecedented number of complaints during the strike, and believes workers were trying to tarnish Onelife’s reputation.) More than a dozen allegations of neglect were substantiated.

I have a list of things I would do differently next time, but I don’t regret the choice to strike for recognition. The retaliation that workers reported experiencing over the month of the campaign — harassment, threats, surveillance — would have likely taken place over two to six months if we had waited for an election, and, given the size of the staff and the rate of turnover, the workers still would have lost.

Labor law functionally ceased to protect the right to organize decades ago, and a simple reinstatement of the rules around “timely elections” is not going to fix that, but there is one change that might. In late summer, the new general counsel at the labor board put out a memo expressing interest in potentially returning to the Joy Silk doctrine, the standard discarded around 1970. If Joy Silk had been the law when subsequent generations tried to organize, Amazon, Starbucks and Whole Foods might have all gone union 10 to 20 years ago. And if Joy Silk had been the standard when caregivers at the Rawlin organized last winter, Ms. Trosko and her co-workers could have had their union soon after they turned in their cards.

Maybe the Rawlin campaign felt like a win because the workers held their majority and finally spoke out about things that bothered them, but I now think that it had more to do with having a choice. All along, Ms. Trosko and the others made choices about what their labor was worth and what they would do with it. They chose to organize together. They chose to strike together. They chose to quit together because they would not use their labor to support a facility that they felt did not care how their residents lived or how they died. The memory care workers did not become a union, but they acted like one.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

A leader of armed confrontations at Wounded Knee and in Washington, he later shifted his focus to education, jobs and cultural renewal.

By Sam Roberts, Published Jan. 13, 2022, Updated Jan. 14, 2022

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/13/us/clyde-bellecourt-dead.html?action=click&module=Well&pgtype=Homepage§ion=Obituaries

Clyde Bellecourt in 1973. He galvanized aggrieved Native American dissidents and sought to educate the American public about Native American history and culture. Credit...Jim Wells/Associated Press

Clyde Bellecourt, a founder of the American Indian Movement who led violent protests in the 1970s at Wounded Knee, S.D., and in Washington over the federal government’s grim record of broken treaty obligations, and who later pressured sports teams to expunge their Native American nicknames, died on Tuesday at his home in Minneapolis. He was 85.

His wife, Peggy Sue (Holmes) Bellecourt, said the cause was complications of pancreatic cancer.

Mr. Bellecourt may not have been as well known to the general public as his fellow activists Dennis Banks and Russell Means, and his accomplishments may have been eclipsed by a checkered record of criminal arrests and internecine brawls, one of which ended with him shot in the stomach by a rival, Carter Camp, the movement’s newly elected national chairman, in 1973.

Regardless, he was a force to be reckoned with.

Mr. Bellecourt galvanized aggrieved but diffuse Native American dissidents after the publication of “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee” (1970), Dee Brown’s scathing chronicle of the government’s historic betrayal of Indian treaties. He also dramatized their political, economic, social, cultural and educational agendas and redeemed his Ojibwe name, Nee-gon-we-way-we-dun, which means “Thunder Before the Storm.” (The Ojibwe are also known as the Chippewa tribe.)

Mr. Bellecourt defended the armed takeover of the Bureau of Indian Affairs office in Washington in 1972 and the 71-day standoff at the town of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota in 1973, during which two Native Americans were killed and a federal agent was paralyzed after being shot.

Wounded Knee was where, in 1890, in one of the last bloody conflicts of the American Indian Wars, about 350 Lakota men, women and children were massacred by U.S. troops.

“We are the landlords of the country, it is the end of the month, the rent is due, and A.I.M. is going to collect,” Mr. Bellecourt was quoted as saying.

By then he had already shifted from the politics of confrontation to educating his fellow Native Americans and the American public in general.

In 1972, he began the bilingual and bicultural Heart of the Earth Survival School. In later years he established the Peacemaker Center for Indian youth; the American Indian Movement Patrol, to provide security for the Minneapolis Indian community; a Legal Rights Center; the Native American Community Clinic; Women of Nations Eagle’s Nest Shelter; the International Indian Treaty Council; and the American Indian Opportunities Industrialization Center, a program to move welfare recipients to full-time jobs.

He also helped create the National Coalition on Racism in Sports and the Media, which urged professional, amateur and school teams to abandon nicknames like Redskins, Indians and Braves, which he saw as demeaning stereotypes.

“We’re trying to convince people we’re human beings and not mascots,” he said in 1992. “They’re making fools of themselves and of us in the process.”

In recent years both the Washington Redskins of the National Football League and Major League Baseball’s Cleveland Indians have dropped their old names.

On Facebook, the Grand Governing Council of the American Indian Movement lauded Mr. Bellecourt’s “fierce dedication, monumental presence and selfless leadership” and said that he “embodied the spirit of the American Indian Movement, the spirit of resistance, the strength and the resolve our people have held for over 530 years.”

On Tuesday, also on Facebook, Peggy Flanagan, Minnesota’s lieutenant governor, wrote that Mr. Bellecourt’s “legacy will live on in the policy changes that created curriculum and classrooms that are more supportive and welcoming of Native youth.”

Clyde Howard Bellecourt was born on May 8, 1936, on the White Earth Indian Reservation in northwestern Minnesota, the seventh of 12 children of Charles and Angeline Bellecourt. His father, an injured World War I veteran, was receiving a disability pension. Their home had no electricity or running water.

Clyde attended a Roman Catholic mission school run by Benedictine nuns on the reservation until he was a teenager. The family then moved to Minneapolis, where he struggled academically, dropped out of high school, failed to find a job and was jailed for burglaries and robberies.

In prison, he met Mr. Banks and Eddie Benton-Banai, who was running a cultural program for Native American inmates. After they were released, in mid-1968, they founded the American Indian Movement with George Mitchell, Charles Deegan and others to help urban Indians deal with discrimination, unemployment, poverty and insufficient housing. Mr. Bellecourt’s older brother Vernon was also active in the movement.

Mr. Bellecourt, who later worked for a utility company, was chosen as the movement’s first chairman and helped launch the so-called Trail of Broken Treaties, a long march from the West Coast to Washington in 1972.

In addition to his wife, whose Japanese American father was interned during World War II, Mr. Bellecourt is survived by four children, Susan, Tonya, Little Crow and Little Wolf; and a number of grandchildren.

He pleaded guilty following his arrest in 1985 in a drug possession case. He later said that the arrest and the two years he spent in prison had helped him break his addiction.