Link to Registration:

https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSe_OGcWbjiakUc89Cfoed25CaV2H3Xm4xdEJHBOaUYDhGdC7Q/viewform?usp=sf_link

Sincere Greetings of Peace:

The “In the Spirit of Mandela Coalition*” invites your participation and endorsement of the planned October 2021 International Tribunal. The Tribunal will be charging the United States government, its states, and specific agencies with human and civil rights violations against Black, Brown, and Indigenous people.

The Tribunal will be charging human and civil rights violations for:

• Racist police killings of Black, Brown, and Indigenous people,

• Hyper incarcerations of Black, Brown, and Indigenous people

• Political incarceration of Civil Rights/National Liberation era revolutionaries and activists, as well as present day activists,

• Environmental racism and its impact on Black, Brown, and Indigenous people,

• Public Health racism and disparities and its impact on Black, Brown, and Indigenous people, and

• Genocide of Black, Brown, and Indigenous people as a result of the historic and systemic charges of all the above.

The legal aspects of the Tribunal will be led by Attorney Nkechi Taifa along with a powerful team of seasoned attorneys from all the above fields. Thirteen jurists, some with international stature, will preside over the 3 days of testimonies. Testimonies will be elicited form impacted victims, expert witnesses, and attorneys with firsthand knowledge of specific incidences raised in the charges/indictment.

The 2021 International Tribunal has a unique set of outcomes and an opportunity to organize on a mass level across many social justice arenas. Upon the verdict, the results of the Tribunal will:

• Codify and publish the content and results of the Tribunal to be offered in High Schools and University curriculums,

• Provide organized, accurate information for reparation initiatives and community and human rights work,

• Strengthen the demand to free all Political Prisoners and establish a Truth and Reconciliation Commission mechanism to lead to their freedom,

• Provide the foundation for civil action in federal and state courts across the United States,

• Present a stronger case, building upon previous and respected human rights initiatives, on the international stage,

• Establish a healthy and viable massive national network of community organizations, activists, clergy, academics, and lawyers concerned with challenging human rights abuses on all levels and enhancing the quality of life for all people, and

• Establish the foundation to build a “Peoples’ Senate” representative of all 50 states, Indigenous Tribes, and major religions.

Endorsements are $25. Your endorsement will add to the volume of support and input vital to ensuring the success of these outcomes moving forward, and to the Tribunal itself. It will be transparently used to immediately move forward with the Tribunal outcomes.

We encourage you to add your name and organization to attend the monthly Tribunal updates and to sign on to one of the Tribunal Committees. (3rd Saturday of each month from 12 noon to 2 PM eastern time). Submit your name by emailing: spiritofmandela1@gmail.com

Please endorse now: http://spiritofmandela.org/endorse/

In solidarity,

Dr. A’isha Mohammad

Sekou Odinga

Matt Meyer

Jihad Abdulmumit

– Coordinating Committee

Created in 2018, In the Spirit of Mandela Coalition is a growing grouping of organizers, academics, clergy, attorneys, and organizations committed to working together against the systemic, historic, and ongoing human rights violations and abuses committed by the USA against Black, Brown, and Indigenous People. The Coalition recognizes and affirms the rich history of diverse and militant freedom fighters Nelson Mandela, Winnie Mandela, Graca Machel Mandela, Rosa Parks, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ella Baker, and many more. It is in their Spirit and affirming their legacy that we work.

https://spiritofmandela.org/campaigns/

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Thursday, November 11, 2021, San Francisco

Timeline of Events:

12:30-1:00 P.M.

Meet at The Ferry Building, grab signs and get ready to march.

1:00-2:00 P.M.

March along the scenic Embarcadero, the route is two miles, flat and wheelchair accessible

2:00-3:30 P.M.

End at Aquatic Park near Hyde St. Pier for a short rally.

COP26 in Glasgow this November has the stated aim of “uniting the world to tackle climate change”.

Yet at the previous 25 COP conferences since 1995, world leaders have repeatedly failed to deliver on this.

We will not accept this failure—governments must act now!

“Stop killing us” is the message from XR Global South groups already suffering the most catastrophic consequences of climate change. We must also provide a voice for the millions of species and future generations who cannot speak for themselves.

XR will continue demanding immediate action to tackle the climate and ecological emergency in the run up to, during and beyond COP26.

Join us. Together we will tell these leaders to listen.

Bring yourself, friends, colleagues, neighbors, schoolmates, children, and community for a demonstration to let the power that be know we are watching them.

We will march with signs, hand crafted puppets, banners, a safety team, and each other to call for our right to safe and healthy planet for future generations by Non-Violent Direct Action.

https://www.facebook.com/events/285993663348587/?acontext=%7B%22source%22%3A%2229%22%2C%22ref_notif_type%22%3A%22event_friend_going%22%2C%22action_history%22%3A%22null%22%7D¬if_id=1633662331965224¬if_t=event_friend_going&ref=notif

To: U.S. Senate, U.S. House of Representatives

End Legal Slavery in U.S. Prisons

Sign Petition at:

https://diy.rootsaction.org/petitions/end-legal-slavery-in-u-s-prisons

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

On the anniversary of the 26th of July Movement’s founding, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research launches the online exhibition, Let Cuba Live. 80 artists from 19 countries – including notable cartoonists and designers from Cuba – submitted over 100 works in defense of the Cuban Revolution. Together, the exhibition is a visual call for the end to the decades-long US-imposed blockade, whose effects have only deepened during the pandemic. The intentional blocking of remittances and Cuba’s use of global financial institutions have prevented essential food and medicine from entering the country. Together, the images in this exhibition demand: #UnblockCuba #LetCubaLive

Please contact art@thetricontinental.org if you are interested in organising a local exhibition of the exhibition.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

A BRILLIANT, BRAVE, BLACK POLITICAL JOURNALIST

|

|

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Rashid just called with the news that he has been moved back to Virginia. His property is already there, and he will get to claim the most important items tomorrow. He is at a "medium security" level and is in general population. Basically, good news.

He asked me to convey his appreciation to everyone who wrote or called in his support during the time he was in Ohio.

His new address is:

Kevin Rashid Johnson #1007485

Nottoway Correctional Center

2892 Schutt Road

Burkeville, VA 23922

www.rashidmod.com

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Freedom for Major Tillery! End his Life Imprisonment!

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

Contact: Governor's Press Office

Friday, May 28, 2021

(916) 445-4571

Governor Newsom Announces Clemency Actions, Signs Executive Order for Independent Investigation of Kevin Cooper Case

SACRAMENTO – Governor Gavin Newsom today announced that he has granted 14 pardons, 13 commutations and 8 medical reprieves. In addition, the Governor signed an executive order to launch an independent investigation of death row inmate Kevin Cooper’s case as part of the evaluation of Cooper’s application for clemency.

The investigation will review trial and appellate records in the case, the facts underlying the conviction and all available evidence, including the results of the recently conducted DNA tests previously ordered by the Governor to examine additional evidence in the case using the latest, most scientifically reliable forensic testing.

The text of the Governor’s executive order can be found here:

https://www.gov.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/5.28.21-EO-N-06-21.pdf

The California Constitution gives the Governor the authority to grant executive clemency in the form of a pardon, commutation or reprieve. These clemency grants recognize the applicants’ subsequent efforts in self-development or the existence of a medical exigency. They do not forgive or minimize the harm caused.

The Governor regards clemency as an important part of the criminal justice system that can incentivize accountability and rehabilitation, increase public safety by removing counterproductive barriers to successful reentry, correct unjust results in the legal system and address the health needs of incarcerated people with high medical risks.

A pardon may remove counterproductive barriers to employment and public service, restore civic rights and responsibilities and prevent unjust collateral consequences of conviction, such as deportation and permanent family separation. A pardon does not expunge or erase a conviction.

A commutation modifies a sentence, making an incarcerated person eligible for an earlier release or allowing them to go before the Board of Parole Hearings for a hearing at which Parole Commissioners determine whether the individual is suitable for release.

A reprieve allows individuals classified by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation as high medical risk to serve their sentences in appropriate alternative placements in the community consistent with public health and public safety.

The Governor weighs numerous factors in his review of clemency applications, including an applicant’s self-development and conduct since the offense, whether the grant is consistent with public safety and in the interest of justice, and the impact of a grant on the community, including crime victims and survivors.

While in office, Governor Newsom has granted a total of 86 pardons, 92 commutations and 28 reprieves.

The Governor’s Office encourages victims, survivors, and witnesses to register with CDCR’s Office of Victims and Survivors Rights and Services to receive information about an incarcerated person’s status. For general Information about victim services, to learn about victim-offender dialogues, or to register or update a registration confidentially, please visit:

www.cdcr.ca.gov/Victim_Services/ or call 1-877-256-6877 (toll free).

Copies of the gubernatorial clemency certificates announced today can be found here:

https://www.gov.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/5.28.21-Clemency-certs.pdf

Additional information on executive clemency can be found here:

https://www.gov.ca.gov/clemency/

###

I don’t usually do this. This is discussing my self. I find it far more interesting to tell the stories of other, the revolving globe on which we dwell and the stories spawn by the fragile human condition and the struggles of humanity for liberation.

But I digress, uncomfortably.

This commentary is about the commentator.

Several weeks ago I underwent a medical procedure known as open heart surgery, a double bypass after it was learned that two vessels beating through my heart has significant blockages that impaired heart function.

This impairment was fixed by extremely well trained and young cardiologist who had extensive experience in this intricate surgical procedure.

I tell you I had no clue whatsoever that I suffered from such disease. Now to be perfectly honest, I feel fine.

Indeed, I feel more energetic than usual!

I thank you all, my family and friends, for your love and support.

Onwards to freedom with all my heart.

—Mumia Abu-Jamal

Questions and comments may be sent to: info@freedomarchives.org

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Resources for Resisting Federal Repression

Since June of 2020, activists have been subjected to an increasingly aggressive crackdown on protests by federal law enforcement. The federal response to the movement for Black Lives has included federal criminal charges for activists, door knocks by federal law enforcement agents, and increased use of federal troops to violently police protests.

The NLG National Office is releasing this resource page for activists who are resisting federal repression. It includes a link to our emergency hotline numbers, as well as our library of Know-Your-Rights materials, our recent federal repression webinar, and a list of some of our recommended resources for activists. We will continue to update this page.

Please visit the NLG Mass Defense Program page for general protest-related legal support hotlines run by NLG chapters.

Emergency Hotlines

If you are contacted by federal law enforcement you should exercise all of your rights. It is always advisable to speak to an attorney before responding to federal authorities.

State and Local Hotlines

If you have been contacted by the FBI or other federal law enforcement, in one of the following areas, you may be able to get help or information from one of these local NLG hotlines for:

- Portland, Oregon: (833) 680-1312

- San Francisco, California: (415) 285-1041 or fbi_hotline@nlgsf.org

- Seattle, Washington: (206) 658-7963

National Hotline

If you are located in an area with no hotline, you can call the following number:

Know Your Rights Materials

The NLG maintains a library of basic Know-Your-Rights guides.

- Know Your Rights During Covid-19

- You Have The Right To Remain Silent: A Know Your Rights Guide for Encounters with Law Enforcement

- Operation Backfire: For Environmental and Animal Rights Activists

WEBINAR: Federal Repression of Activists & Their Lawyers: Legal & Ethical Strategies to Defend Our Movements: presented by NLG-NYC and NLG National Office

We also recommend the following resources:

Center for Constitutional Rights

Civil Liberties Defense Center

- Grand Juries: Slideshow

Grand Jury Resistance Project

Katya Komisaruk

Movement for Black Lives Legal Resources

Tilted Scales Collective

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

In closing arguments in the Varsity Blues trial, prosecutors want to focus on bribes, but the ways in which universities cater to rich families is also on trial.

By Anemona Hartocollis, Oct. 6, 2021

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/06/us/varsity-blues-college-admissions-trial-usc.html

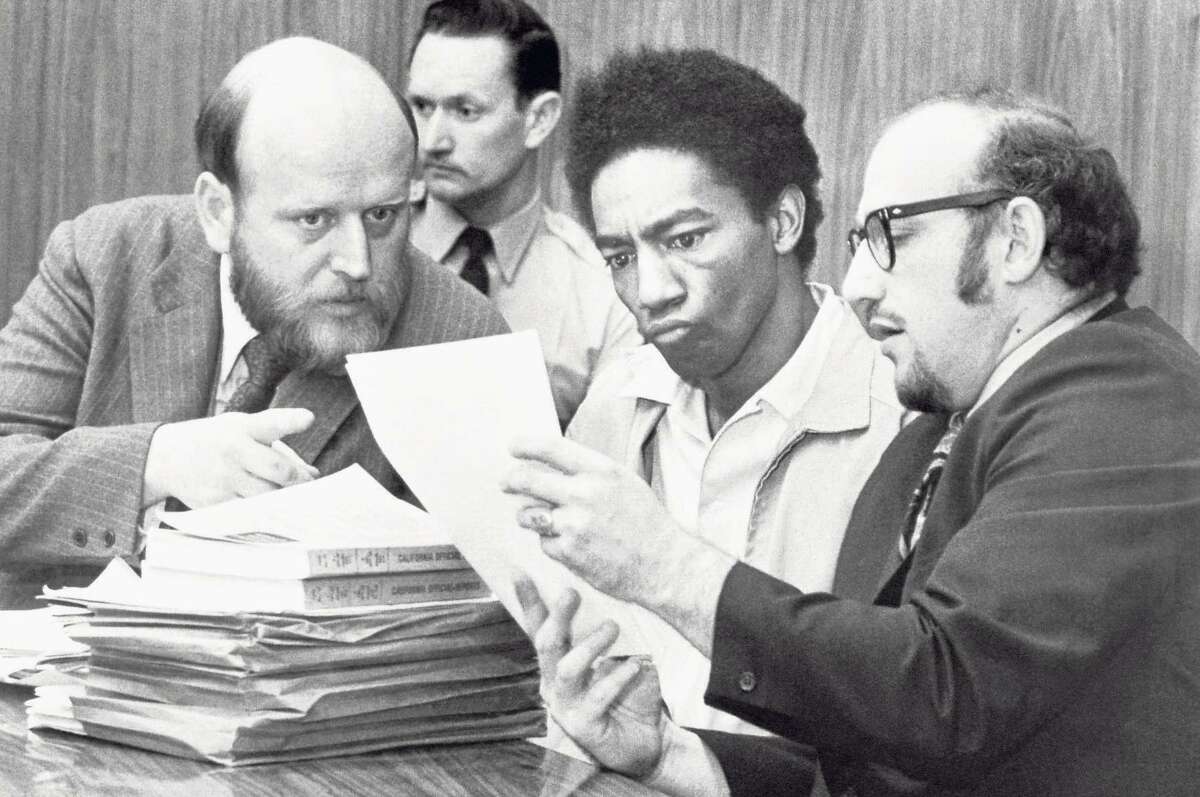

Gamal Abdelaziz, center, is accused of paying $300,000 to get his daughter into the University of Southern California as a top-ranked basketball recruit. Credit...Photo by Jessica Rinaldi/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

As lawyers give their closing arguments in the first trial of the college admissions scandal on Wednesday, one question may hang over the Boston courtroom: Will the jury, in a city where town-and-gown suspicion can be strong, see the trial as a tale of a flawed, possibly corrupt college admissions system, or the arrogance and immorality of wealthy men?

From the opening day of the federal trial three weeks ago, the prosecution tried to steer the jury away from the college admissions system. Rather, prosecutors said the focus should be on the actions of the two men on trial, John Wilson, a private-equity financier and former Gap and Staples executive, and Gamal Abdelaziz, a former Wynn Resorts executive.

Prosecutors say the two men paid bribes to a college counselor to get their children into the University of Southern California as bogus athletic recruits, while the defendants say they thought they were making legitimate donations. They are the first to stand trial in the investigation known as Operation Varsity Blues, with many other similarly accused parents choosing to plead guilty.

“This case is not about wealthy people donating money to universities in the hope that their children get preferential treatment in the admissions process,” Leslie Wright, an assistant U.S. attorney, said in her opening statement in the imposing federal court near the Boston seaport.

“The defendants are not charged with crimes for having donated money to U.S.C. If that was all they had done, we would not be here today.”

The trial is taking place in the same courthouse where, three years ago, Harvard was accused of systematically discriminating against Asian American applicants in admissions.

During that trial, a packed house listened raptly to testimony about how some applicants with connections to donors might be put on the “dean’s interest list”; others might be designated as athletic recruits, which gave them an enhanced chance of getting in. The plaintiffs read out loud a 2013 email from the dean of the Harvard Kennedy School in which he thanked the dean of admissions for “the folks you were able to admit” and exulted that someone “has already committed to a building.”

A federal judge and an appeals court found that Harvard did not discriminate, and the plaintiffs are asking the Supreme Court to hear the case.

In the current case, prosecutors must overcome the ingrained suspicion that college admissions are tainted, said Jeffrey M. Cohen, a former federal prosecutor and associate professor at Boston College Law School. “The goal of the defense is to suggest that although distasteful, the defendants were playing along with the rules as they understood them to be,” Mr. Cohen said.

On the other hand, Mr. Cohen said, the jury may see that a line has been crossed in an unsavory system. “We’ve generally accepted that if you donate a building to a university you get some preference to get in,” he said. “We don’t agree that if you lie and cheat to get in, you should get in.”

The admitted mastermind behind the admissions scheme, William Singer, has pleaded guilty and is cooperating with the government, though he has not yet been sentenced. He ran a college counseling business out of California called the Key that included a mix of legitimate services, like tutoring, and fraudulent ones, like helping students cheat on college admissions tests and fabricating athletic credentials, according to prosecutors.

Mr. Singer, who is known as Rick, characterized what he was doing as getting students admitted through a “side door,” and boasted that he could get the children of wealthy parents designated as varsity-level athletes when they were nothing of the kind.

The government says that he did it by bribing coaches and others who were working with him, at schools including U.S.C., Stanford, Yale and Georgetown, and that it strains credulity to think sophisticated businessmen like Mr. Wilson and Mr. Abdelaziz did not realize that. Mr. Wilson wrote off his payments as business expenses and charitable contributions, prosecutors say.

Mr. Abdelaziz is accused of paying Mr. Singer $300,000 to get his daughter, Sabrina, into U.S.C. as a top-ranked basketball recruit even though she did not make the varsity team in high school. Mr. Wilson is accused of paying Mr. Singer $220,000 to have his son designated as a water polo recruit.

Some of the money actually did go to the university’s athletic programs, like $100,000 from the Wilson family, according to prosecutors. Other payments went into the pockets of those involved, prosecutors say.

Five years later, Mr. Wilson agreed to pay $1.5 million in what Mr. Singer called “donations,” according to the prosecutor’s opening statement, to help his twin daughters get into Stanford and Harvard. Mr. Singer offered to present them as sailors because their father had a home in Hyannis Port, Mass., though Mr. Wilson demurred that the one who wanted to go to Stanford hated sailing. At that point, Mr. Singer was cooperating with the government, which had concocted the ruse to see if Mr. Wilson would go along, according to the prosecution.

During the trial, the defense lawyers have tried to establish the “mind-set” of the two defendants, who did not know each other, by saying they did not realize that Mr. Singer, who prosecutors admit kept up a facade of legitimacy, was lying to them.

“It’s not illegal to do fund-raising, not illegal to give money to a school in the hopes that your kid will get in,” Brian Kelly, Mr. Abdelaziz’s lawyer, said. “So that’s his mind-set.”

Mr. Cohen, the law professor, said the details of the testimony might make a difference there.

Bruce Isackson, one of the parents who has pleaded guilty, choked up on the stand while testifying for the prosecution in the hope of getting a lighter sentence. He said he asked to have his name removed from a place of honor at his children’s school because he was so embarrassed by his role in the Varsity Blues scandal.

“Your situation was unique to you, correct?” asked Mr. Kelly, who was part of the team that prosecuted the mobster James (Whitey) Bulger. “You don’t know what these other parents’ mind-sets were.”

“I could not know that,” Mr. Isackson replied.

Yet later in his testimony, Mr. Isackson, a real estate developer in the San Francisco area, was adamant that the scheme described by the government was as clear as day. “You’d have to be a fool” not to know what was going on, he testified.

But the details can be complicated.

For one thing, Mr. Wilson’s son, Johnny, really was a competitive water polo athlete in high school; he was a fast swimmer and “a quiet grinder” who had the fortitude to “just put your head down and swim,” his high school coach, Jack Bowen, testified for the defense. But Mr. Bowen also testified that some elements, like a few awards, of the athletic profile that Mr. Singer submitted to U.S.C. on the student’s behalf were false.

And in the end, Mr. Bowen testified that he was “a little surprised, I wouldn’t say shocked,” that Johnny Wilson had been admitted.

Kitty Bennett and Jack Begg contributed research.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

The 2004 conviction, which was brought by a former Houston narcotics officer now at the center of a policing scandal, would be set aside if the governor approves.

By Shaila Dewan, Oct. 5, 2021

A mural in Houston of George Floyd, whose death touched off a national debate over race and policing in 2020. Credit...Montinique Monroe for The New York Times

In 2004, George Floyd was one of scores of people arrested on the word of a Houston narcotics officer, Gerald M. Goines, who said he had watched Mr. Floyd hand over a “dime rock” of crack cocaine during an undercover drug buy.

But after a botched drug raid ended with the death of a couple in their Houston home in 2019, Mr. Goines, who is now retired, became the center of a massive policing scandal that resulted in felony charges against nine officers.

Prosecutors say Mr. Goines fabricated evidence to conduct the raid, including by inventing an informant, and have charged him with two counts of felony murder. He also faces federal civil rights charges, but has denied the allegations.

Now the state parole board has recommended a posthumous pardon in the Houston case for Mr. Floyd, whose killing during an unrelated arrest in Minneapolis in 2020 touched off a national debate over race and policing.

The pardon was requested by the Harris County Public Defender’s Office and endorsed by the district attorney, Kim Ogg.

Mr. Floyd and Mr. Goines “have come into the spotlight on opposite sides of the same issue: the vast unfairness of the United States’ criminal justice system, and specifically, the grotesque abuses of power by police officers,” Allison Mathis, a public defender, wrote in the 241-page pardon application.

Granting the pardon, she said, would show that Texas was interested in “fundamental fairness” and increasing accountability for police officers “who break our trust and their oaths.”

The board’s vote for a pardon on Monday was unanimous, but a final decision will be made by Gov. Greg Abbott. The governor’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Mr. Floyd initially fought the charges, then accepted a plea deal in the case and was sentenced to serve 10 months. Had he gone to trial, the pardon application said, he could have been branded a habitual offender and faced a minimum sentence of 25 years.

Ben Crump and Antonio Romanucci, civil rights lawyers who represent Floyd family members, called upon the governor to grant the pardon, but added that passing criminal justice reform measures was even more important. “Like the U.S. Senate, the Texas Legislature left undone the hard but necessary work of protecting residents from unacceptable police violence,” they wrote in a statement.

The deadly Houston raid occurred in January 2019, when officers burst into the home of a Navy veteran, Dennis Tuttle, and his wife, Rhogena Nicholas, working on information that drugs had been bought there by Mr. Goines and others. A shootout ensued that left Mr. Tuttle and Ms. Nicholas dead and five officers wounded. Afterward, prosecutors said it appeared that Mr. Goines had lied about the drug purchases.

The district attorney’s office identified more than 150 people, including Mr. Floyd, who were convicted in cases where Mr. Goines was the sole witness or submitted a search warrant affidavit, said Joshua Reiss, the chief of the district attorney’s post-conviction writs division. He said his office attempted to notify all of them so they could petition to have their convictions vacated.

Mr. Floyd probably never received his letter, which was sent to a Houston address after he had moved to Minneapolis.

Last year a pair of brothers, Steven and Otis Mallet Jr., were exonerated on the grounds that Mr. Goines had falsified evidence against them in an unrelated case. The pattern established by that case and the botched raid, Mr. Reiss said, means that other defendants who want relief will not be required to prove that Mr. Goines lied, only that their conviction rested on evidence he provided.

Many of the defendants have been difficult to find, Ms. Mathis, the public defender, said. She filed the pardon application partly in hopes that the publicity would help reach more of them.

While most of the cases involved low-level drug offenses with relatively short sentences, she said, the prior convictions could make punishment harsher if the person was arrested again.

Nicole DeBorde, a lawyer for Mr. Goines, said he had pleaded not guilty to the charges against him. She said that the prosecutors’ move to dismiss convictions in his previous cases was a way of bolstering the criminal case against him in the drug raid.

“There’s no new evidence of any kind to indicate that there’s any misconduct whatsoever or any problem with any of those previous arrests,” she said.

Mr. Goines’s former partner, Steven Bryant, pleaded guilty to falsifying records and faces up to 20 years in prison.

According to a report in Texas Monthly, Texas has granted a posthumous pardon only once, in a rape case where the defendant was cleared by DNA evidence.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Tesla must pay $137 million to a Black employee who sued for racial discrimination

By Joe Hernandez, October 5, 2021

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

A federal jury in San Francisco has ordered Tesla to pay a former Black contractor $137 million over claims that he was subjected to racial discrimination at work.

Owen Diaz, who worked as a contract elevator operator at Tesla's factory in Fremont, Calif., from 2015 to 2016, said in his lawsuit that he and others were called the N-word by Tesla employees, that he was told to "go back to Africa" and that employees drew racist and derogatory pictures that were left around the factory.

The suit said Diaz was excited to go to work for Tesla, but that instead of a "modern workplace," he found a "scene straight from the Jim Crow era."

Diaz says nothing was done to stop it

Diaz said that he complained about the discriminatory treatment to Tesla and the contracting companies Citistaff and nextSource, but that nothing was ever done to stop it.

"I'm gratified that the jury saw the truth and that they sent a message to Tesla to clean up its workplace," Larry Organ, one of Diaz's attorneys, told NPR.

The jury award included $130 million in punitive damages and $6.9 million in emotional damages, according to the verdict. Organ said he believed it was the largest award in a racial harassment case involving a single plaintiff in U.S. history.

"Owen and I both hope that this sends a message to corporate America to look at your workplace and, if there are problems there, take proactive measures to protect employees against racist conduct," Organ added. "It is happening, and we need to do something about it."

Tesla says its workplace culture has "come a long way"

Valerie Capers Workman, Tesla's vice president of people, said in a statement on the automaker's website that witnesses at trial corroborated the fact that people used the N-word on the factory floor, but that those witnesses also said the word was often used in a "friendly" manner. Workman said that Tesla followed up on Diaz's complaints, and that the staffing agencies fired two contractors and suspended another.

"While we strongly believe that these facts don't justify the verdict reached by the jury in San Francisco, we do recognize that in 2015 and 2016, we were not perfect. We're still not perfect. But we have come a long way from 5 years ago," Workman said.

"The Tesla of 2015 and 2016 (when Mr. Diaz worked in the Fremont factory) is not the same as the Tesla of today," she added.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Photographs by Damon Winter, Text by Jesse Wegman, October 7, 2021

Mr. Winter is a staff photographer on assignment in Opinion. Mr. Wegman is a member of the editorial board.

Twenty years ago, Judy Bolden served 18 months in a Florida prison. She has been free ever since, but she is still barred from voting by the state until she pays all court fines and fees associated with her conviction.

When Ms. Bolden sat to be photographed by The Times earlier this year, she said she had received a letter informing her that her outstanding debt was a few hundred dollars. Then she checked the Volusia County website and learned that she actually owes nearly $53,000. “I was so taken aback,” she said. “I was like, What? That’s not right. I was just deflated. It’s like, when is this going to end?”

Ms. Bolden is one of more than 700,000 people in Florida who are barred from voting because they can’t afford the financial obligations stemming from a prior felony conviction. “It’s like I’m not a citizen,” she said. “That’s what they’re saying.”

Earlier this year we asked Floridians whose voting rights had been denied because of a criminal conviction to sit for photographs, wearing a name tag that lists not their name but their outstanding debt — to the extent they can determine it. This number, which many people attempt to tackle in installments as low as $30 a month, represents how much it costs them to win back a fundamental constitutional right, and how little it costs the state to withhold that right and silence the voices of hundreds of thousands of its citizens. The number also echoes the inmate identification number that they were required to wear while behind bars — another mark of the loss of rights and freedoms that are not restored upon release.

This is the way it’s been in Florida for a century and a half, ever since the state’s Constitution was amended shortly after the Civil War to bar those convicted of a felony from voting. That ban, like similar ones in many other states, was the work of white politicians intent on keeping ballots, and thus political power, out of the hands of millions of Black people who had just been freed from slavery and made full citizens.

Even as other states began reversing their own bans in recent years, Florida remained a holdout — until 2018, when Floridians overwhelmingly approved a constitutional amendment restoring voting rights to nearly everyone with a criminal record, upon the completion of their sentence. (Those convicted of murder or a felony sexual offense were excluded.)

Democratic and Republican voters alike approved the measure, which passed with nearly two-thirds support. Immediately, as many as 1.4 million people in the state became eligible to vote. It was the biggest expansion of voting rights in decades, anywhere in the country.

That should have been the end of it. But within a year, Florida’s Republican-led Legislature gutted the reform by passing a law defining a criminal sentence as complete only after the person sentenced has paid all legal financial obligations connected to it.

The state adds insult to injury by making it difficult, if not impossible, for many of these people, like Ms. Bolden, to figure out what they owe. There is no central database with those numbers, and counties vary in their record-keeping diligence. Some convictions are so old that there are no records to be located.

This isn’t just Kafkaesque. It may well be the deciding factor in Florida elections: Donald Trump carried the state by roughly 370,000 votes in 2020, or about half the number of Floridians who are denied the right to vote because they can’t afford to pay their fines and fees.

That group includes Marq Mitchell, 30, who owed, as best as he can tell, $7,331.89 stemming from convictions back to when he was 16 years old. He wasn’t aware of the debt until he tried to register to vote and received a notice from the county’s clerk of court.

“I have no idea what I have to pay,” he said. “I just know every time I reach out, it’s a different number, and it’s increasing.”

Right now, Mr. Mitchell isn’t paying anything toward his debt. He asked the court to convert it to community service, which would translate to roughly 700 hours of work. “That would be a lot more realistic than expecting me to shovel out $7,000 while still being able to survive and eat,” he said.

For the lucky ones who can determine what they actually owe, the state layers one obstacle on top of another. It continues to add new fees for court appearances. It sells off the debt to private collection agencies, which tack on interest of up to 40 percent. Most crippling of all, it suspends the drivers’ licenses of people who miss a payment. In a state where about 90 percent of people use a car to get to work, a suspended license makes it essentially impossible for people to earn the money they need to pay their fines and fees.

“The last four times I’ve been to jail has been because of driving on a suspended license,” Daniel Bullins said. Mr. Bullins, 42, lives in Melbourne, and served about two years in prison.

“The sad part is my mom doesn’t like cops now, and that breaks my heart. She’s 70, there’s no reason for her not to like cops, except for seeing what I’ve gone through,” he said.

Mr. Bullins went to the courthouse to pay down his debt, only to learn that it had been sold off to a private collection agency that charges 25 percent interest. “How are you going to sell somebody’s agony to a company and compound it?” Mr. Bullins asked. “It feels like that’s what they want: some way to pull you back in. It’s like ‘Goodfellas.’ You get away and they bring you back in.

“When prisons became big business, every part of the system became big business,” Mr. Bullins went on. “The whole tower is built on misery.”

Sergio Thornton has been out of prison since 2012, but he still owed about $20,000 when he was photographed — “all fines and fees, just for selling $40 worth of drugs,” he said. His original debt was more than double that amount, upward of $40,000, as he recalls.

“I’m sitting in the courtroom, telling the judge that the only way I could come up with that kind of money is to commit another crime,” Mr. Thornton said. He is currently raising three girls and said he is supposed to be paying $60 a month toward his legal debt, “but with school coming and rent, you got to pick which bill to pay.” When he fell three months behind in legal debt payments, his license was suspended. The day before he spoke to The Times, he had been laid off from a landscaping job that paid him $13 an hour.

For many, paying thousands of dollars in legal debt isn’t worth the price. “I’m not paying them nothing,” Frank Summerville, a 34-year-old father of four living in Cocoa, said. “I’m not going to give them a dollar. I gave them four years of my life.” Mr. Summerville got out of prison in 2016 and now works as a mechanic and boat builder. He is qualified to work on airplanes and helicopters, but says he can’t get the clearance required to work at airports because of his convictions. He refuses to pay down his debt and get trapped in a system that seems designed to thwart him. “Why are we going to take our savings and dump it into something that ain’t going to make a difference?”

Aniesha Lynn Austin, 48, hasn’t been paying her debt of almost $600, either, primarily because she can’t figure out how to. “I didn’t even know I owed this until I was actually released off parole,” she said. Ms. Austin served 27 years in prison before her release in March 2019. She has worked as a sales manager and as the vice president of Change Comes Now, a nonprofit organization that provides services to people coming out of prison. “We’re still trying to find the actual link to pay it. It is from 1996. Trying to is half the battle.”

Raquel Wright, 46, of Vero Beach, has been out for seven years and owed more than $54,000 when she was photographed. While on work-release, the state withheld 55 percent of her wages — she earned $8.50 per hour, at AT&T — to cover her room and board, and a smaller percentage to pay down her legal debt. But she hasn’t been able to get a full-time job since she got home, in part because she doesn’t pass background checks, so she has not kept up with payments. With money tight and a 16-year-old daughter at home, other considerations come first. “I have her day-to-day care: feeding, clothing, basic needs. I have our phone bills. I have my car insurance. I have medical bills.” As for the legal debt, Ms. Wright said, “I’m never going to be able to pay that off in my lifetime. Especially now, being that my employment is hindered with this charge. I’m always told I’m overqualified or I didn’t pass the background check.”

For some people, getting out from under their legal debt is closer to being a reality. Alan Grate, 59, had just started a job building boats when he spoke to The Times. “I started out at $14.45 an hour, get a raise every 90 days. I ain’t never in my life had a job making that kind of money,” Mr. Grate said. He owes $1,219.50 in court fines and fees after serving 14 and a half years in prison, and pays $94 a month toward his debt. “At my age, I need to be able to go 10 years straight. I need that Social Security. That’s one of my goals: buying a house. I don’t want to pay rent all my life. I don’t know how much time I got left on this earth.”

Then there are the people whose debt is so massive they are effectively barred from voting not just in this life, but for many lifetimes after. Karen Leicht, 64, faced 50 years behind bars for a minor role in an insurance fraud and money laundering scheme that involved several co-defendants. Eventually she negotiated her sentence down to 30 months, which she served, but she could not negotiate the restitution — more than $59 million. Trying to pay down an amount of that size is “an exercise that’s meaningless,” she said. “When the judge sentenced me and he was deciding what to put for the amount, he said, ‘It doesn’t matter what you pay monthly, you will never pay it off.’ He didn’t even put a monthly amount in.”

At this point, voting is the least of Ms. Leicht’s concerns. “I am 64. There’s no possibility that I could ever retire because they took everything I had, including my condo. If I don’t work, that’s it,” she said.

Even relatively small debts can be permanently disenfranchising for people who simply don’t bring in enough money to pay them off. General Peterson, 63, served a total of three and a half years on three convictions and believes he still owes around $1,100 in fees. He is retired and using his Social Security check to make monthly payments of $30 on the debt. “You want to help me pay it? That’d be fine with me,” he said.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

By Farah Stockman, Oct. 7, 2021

Ms. Stockman is a member of the editorial board. This essay is adapted from her forthcoming book, “American Made: What Happens to People When Work Disappears.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/07/opinion/globalization-work-trump-social-justice.html

In 1998, Shannon Mulcahy’s boyfriend beat her up so badly that prosecutors in Indiana decided to press charges. She hid in a closet rather than obey the subpoena to testify in court. How could she help convict the man who put a roof over her head? Over her son’s head? Eventually, she left him. Shannon, a white woman in her 20s, got the money and the confidence to strike out on her own from a job at a factory. She worked at a bearing plant in Indianapolis for 17 years, rising to become the first woman to operate the furnaces, one of the most dangerous and highly paid jobs on the factory floor.

I first met Shannon in 2017, shortly after her bosses announced that Rexnord, the bearing factory where she worked, was shutting down and moving to Mexico and Texas. I followed her for seven months as the plant closed down around her, watching her agonize about whether she should train her Mexican replacement or stand with her union and refuse. I also followed two of her co-workers: Wally, a Black bearing assembler who dreamed of opening his own barbecue business, and John, a white union representative who aspired to buy a house to replace the one he’d lost in a bankruptcy.

One of the biggest takeaways from the experience was that some of the most consequential battles in the fight for social justice took place on factory floors, not college campuses. For many Americans without a college degree, who make up two-thirds of adults in the country, the labor movement, the civil rights movement and the women’s liberation movement largely boiled down to one thing: access to good-paying factory jobs.

Shannon had experienced more abuse and workplace sexual harassment than anyone I knew. Yet, she hadn’t been drawn to #MeToo or the presidential candidacy of Hillary Clinton. To Shannon, women’s liberation meant having a right to the same jobs men had in the factory. She signed her name on the bid sheet to become a heat-treat operator, even though no woman had ever lasted in that department before. Heat-treat operators were an elite group, like samurai warriors and Navy SEALs. They worked with explosive gases. The men who were supposed to train Shannon tried to get her fired instead. “Heat treat is not for a woman,” one said.

She persisted. Heat-treat operators earned $25 an hour, more money than she’d ever earned in her life. She wasn’t going to let men drive her away. She wasn’t above using her sexuality to her advantage. She flirted with the union president and wore revealing shirts into the heat-treat department. “Am I showing too much cleavage?” she’d ask. She paid particular attention to Stan Settles, a much older man who knew how to run every furnace. If his shirt came untucked while he was bending over, exposing the top of his butt, Shannon would issue a solemn warning: “Crack kills, Stan.”

In the end, Stan took her under his wing and taught her everything about the furnaces that there was to know. By the time I met Shannon, she was the veteran in charge of training new heat-treat operators. She took pride in the fact that she didn’t depend on a man — even, and perhaps especially, Uncle Sam.

Shannon’s feminism felt radically different from the women’s liberation movement that I grew up with. The movement I knew about was inspired by Betty Friedan’s “The Feminine Mystique,” the groundbreaking second-wave feminist tract that spoke of the emptiness and boredom of well-off housewives. That movement focused heavily on breaking glass ceilings in the white-collar world: the first woman to serve on the Supreme Court (Sandra Day O’Connor, 1981); the first female secretary of state (Madeleine Albright, 1997).

But low-income women, especially Black women, have always worked, not out of boredom but out of necessity. Their struggles, which the labor historian Dorothy Sue Cobble has called “the other women’s movement,” garnered far less media coverage. Who knows the name of the first female coal miner? How many know the full name of “Mother Jones,” the fearless labor organizer once labeled “the most dangerous woman in America” because legions of mine workers laid down their picks at her command? (It was Mary Harris Jones.)

It was not until 1964 that the law enshrined workplace protections against discrimination on the basis of sex as well as race. Women were added to the Civil Rights Act at the last minute, a poison pill meant to ruin its chances. But the bill passed, changing the course of history. The percentage of working women rose to 61 percent in 2000 from 43 percent in 1970. From 1976 to 1998, the number of female victims of intimate partner homicides fell by an average 1 percent per year. (The number of male victims of intimate partner homicide fell even more steeply.)

But the Civil Rights Act did not benefit all women equally. By far, those who reaped the greatest rewards were college-educated white women who joined the professional world, who grew rich on economic shifts that swept their blue-collar sisters’ jobs away. Today, well-educated women — who tend to be married to well-educated men — sit atop the country’s financial pyramid.

The struggles of blue-collar women against a system of occupational segregation — called “Jane Crow” in Nancy MacLean’s book “Freedom Is Not Enough: The Opening of the American Workplace” — continued against the headwinds of economic challenges. For instance, in 1969, a female steelworker named Alice Peurala in Chicago had to sue to get a job assigned to a man with less seniority. She won and went on to become president of the Steelworkers local. But in the years that followed, the steel industry collapsed. Eventually, her plant shut down for good.

In 2016, about three million American women worked in manufacturing, a far greater number than worked as lawyers or financiers. Yet the urgent needs of blue-collar women for quality child care, paid medical leave and more flexible work schedules rarely made it into the national conversation, perhaps because the professional women who set the agenda already enjoyed those benefits.

So much of the debate about sexism and women’s rights focuses on how to negotiate salaries like a man and get more women onto corporate boards. Meanwhile, blue-collar women are still struggling to find jobs that pay $25 an hour. And the United States remains one of the only countries with no federal law mandating paid maternity leave.

To Wally, the Black man I followed, the major success of the civil rights movement was that Black people got a chance at better jobs on the factory floor. Black people had been barred from operating machines, from tractors to typewriters, well into the 20th century, according to “American Work: Four Centuries of Black and White Labor,” by Jacqueline Jones.

Wally’s uncle Hulan managed to get hired at the bearing plant in the early 1960s, with the help of the N.A.A.C.P. But like every other Black man there, he’d been assigned a janitor’s job. Hulan complained to the union steward. “There are only so many jobs in this building,” the steward replied. “If you take one, that means that our sons or son-in-law or our nephew can’t have it.” The day after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 passed, Hulan asked his boss for a chance to operate a machine. The boss, who was known as tough but fair, sent him to the grinding department. But the white man assigned to train him refused to even speak to him. Hulan had to learn by watching from afar.

Eventually, Hulan figured out how to do the job. Over the years, he won over his white co-workers and was promoted to foreman, the first (and last) Black man to serve in that role at the plant.

For Uncle Hulan’s generation, the blue-collar battles for social justice were largely successful. Factory floors today tend to be far more racially integrated than the corporate boards that run them. But in many ways, the progress was short lived. As soon as Black workers began to get good jobs in the factories, factories began moving away.

By the time Wally’s generation came of age, several of the largest factories in Indianapolis had closed down. Many of the boys in Wally’s neighborhood found work on the corner, selling dope. More than 10 percent of the Black boys in Wally’s neighborhood ended up in prison as adults. Wally served time in prison, too. “I was locked up,” he told his co-workers. “I’m blessed to have this job.”

In many ways, the decline in American manufacturing hit Black people the hardest. According to a 2018 study of the impact of manufacturing employment on Black and white Americans from 1960 through 2010, the decline in manufacturing contributed to a 12 percent overall increase in the racial wage gap for men.

When you follow a dying factory up close, its easy to see how globalization left a growing group of people competing for a shrinking pool of good factory jobs. Affirmative action becomes more fraught as good jobs get scarce and disappear.

Even for John, the white man I followed, factories were sites of important social protest. If a boss disciplined a worker for refusing to wear safety glasses, John thought that all the other workers should take off their safety glasses and hurl them on the floor, forcing the manager to bring back the disciplined worker or shut down the whole assembly line.

John was a die-hard union man who came from a long line of union men. His grandfather and great-grandfather had been coal miners. His father-in-law had been an autoworker. To John, factories were places where the working class fought pitched battles with the company for higher pay and shorter working hours. He traced his identity to the miners and steelworkers who had been beaten, arrested and even killed for demanding an eight-hour workday and a day off every week. That’s why nothing stuck in John’s craw like the phrase “white privilege.” The words implied that his people had been handed a middle-class life simply because they were white. In John’s mind, his people had not been given dignity, leisure time, safer working conditions or decent wages just because they were white; they had fought for those things — and some of them had died in the fight.

After the bosses announced that the factory would close, he walked around the plant urging his fellow workers to refuse to train their Mexican replacements, in a last-ditch effort to keep the factory in Indianapolis. As the shutdown at Rexnord continued, John preached about the need for worker solidarity.

“If you want it, fight for it,” he told his union brothers and sisters of their doomed plant. “I’ll fight with you.”

I began to understand why white workers tended to view the closure of the factory — and the election of Donald Trump — differently from their Black co-workers. Over the course of a decade, John had seen his wages sink from $28 an hour to $25 an hour to $23 an hour. After the plant closed, he struggled to secure a job that paid $17 an hour. His declining earning power hadn’t been tempered by social progress, like the election of a Black president. To the contrary, his social standing had waned. Rich white C.E.O.s sent blue-collar jobs to Mexico. But when blue-collar workers complained about it, college-educated people dismissed them as xenophobes and racists.

Working-class white men at the bearing plant may not have wanted to share their jobs with Black people and women. But they had done it. And now that Black people and women worked alongside them on the factory floor, everyone’s jobs were moving to Mexico. It was more than many white workers could take. One white man at the plant quit and walked away from more than $10,000 in severance pay simply because he couldn’t stand watching a Mexican person learn his job. “It’s depressing to see that you ain’t got a future,” he told me. One of John’s best friends volunteered to train. “I don’t hate you, but I hate what you’re doing,” John told him. They never spoke again.

The union reps, nearly all of whom were white, saw training their replacements as a moral sin, akin to crossing a picket line. But many of the Black workers and women did not agree. It had not been so long ago, after all, that the white men had refused to train them. Black workers had not forgotten how the union had treated their fathers and uncles. Many considered the refusal to train the Mexicans racist. The most unapologetic trainers were Black.

The announcement that the factory would close, the election of Donald Trump and the arrival of Mexican replacements at the plant took place within the span of three months, in 2016, unleashing a toxic mix of hope, rage and despair. In the years that have passed since, the workers scattered like brittle seeds, trying to start their lives over again.

Economists predicted that they’d get new jobs — even better jobs than they’d had before. Some did. But most of the workers I kept track of ended up earning about $10 an hour less than they had been making before. One started a bedbug extermination company. Another joined the Army. Another sold everything he owned and bought a one-way ticket to the Philippines, determined to make globalization work in his favor, for once. Wally made progress with his barbecue business, until an unforeseeable tragedy struck. John agonized over whether to become a steelworker again or take a job in a hospital that had no union. Shannon stayed jobless a long time, which made her miserable. The old factory continued to appear in her dreams for years.

Of course, for every story like Shannon’s, there’s a story about a woman in India or China or Mexico who has a job now — and more financial independence — because of a new factory. Globalization and social justice have many sides.

But those foreign workers don’t vote in American elections. The fate of our democracy does not depend on them the way it hinges on voters like Shannon, Wally and John. The American experiment is unraveling. The only way to knit it back together is for decision makers in this country, nearly all of whom have college degrees, to reconnect with the working class, who make up a majority of voters.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

https://www.change.org/p/demand-that-ktvu-2-reinstate-anchor-frank-sommerville-and-revoke-suspension?recruiter=1209470378&recruited_by_id=57d56710-25e3-11ec-bf5e-a18b99a9762c&utm_source=share_petition&utm_campaign=share_petition&utm_medium=copylink&utm_content=cl_sharecopy_30931848_en-US%3A3

As of September 25, 2021, local Bay Area television station KTVU 2 has put evening anchor, Frank Somerville, on indefinite suspension. This suspension comes after Somerville and KTVU news director, Amber Eikel, were at odds over his request for 46-seconds of sidebar tagline commentary at the tail-end of the 9/24 broadcast's coverage of the Gabby Petito case. Because the case involves domestic violence, Somerville requested the airtime to briefly discuss and highlight national statistics showing the alarmingly higher rates of domestic violence among African-American, and other women of color, as compared to Caucasian women. This was in an effort to also highlight the disparate, significantly lower amount of media coverage given to such statistics, and to other cases similar to the Petitio case, but involving African-American women. Somerville's request was denied, and he was informed of his suspension the next day 9/25.

As the most populous state in America, with 38Million+ residents, California has long been at the forefront of change, both politically and socially. Here, now, we have a case in front of us in which a beloved local news anchor is being silenced, and openly and publicly chastised for wanting to do his job and report on a social ailment which has long gone ignored and trivialized. In the current climate of racial injustice and unrest, it is now that it is most important to continue examining such racial disparities..... no longer as matters of politics, economics, social policy, or mere statistics, but simply as a matter of sheer humanity and human decency. Networks like NBC and ABC often like to make big claims that they are the most trusted news sources and have the most trustworthy anchors. How, though, can we expect to put our trust in our major media outlets when local anchors are being silenced from reporting on major racial injustices/inequalities/disparities? Isn't the act of putting our trust in our media outlets dependent on hearing the truth?

Frank Somerville attempted to report on, and present facts on, the alarming rates at which women of color are experiencing domestic violence, and the continuing lack of widespread media coverage. For this, he was suspended, and now it is up to the people of the Bay Area and California to say this cannot, and must not be allowed.!! The president of the Oakland chapter of the NAACP, George Holland, Sr., Esq., wrote a letter directly to KTVU's general manager, Mellynda Hartel, demanding that Frank Somerville be reinstated. He also held a press conference Sat Oct 2, in support of Mr. Somerville's integrity and his desire to bring to light the lack of coverage of high rates of domestic violence among women of color (i.e- African-American, Latina, and Native-American women), including alarmingly higher rates of death from domestic violence. He has expressed the support of the national NAACP in all efforts to subdue the silencing of such voices. So I urge you to please set aside your politics, your socioeconomics, and any preconceptions you hold, and please just reach into your heart and imagine a world in which your own sisters, daughters, nieces, and granddaughters will never have to know the torment of an abuser. Please help send a message to KTVU's News Director, Amber Eikel, HR manager Chris Nohr, and General Manager, Mellynda Hartel, that the truth should never be silenced. No journalist committed to reporting the truth should ever have to worry about being silenced in a country which is supposed to guarantee freedom of the press, just for the sake of not opening our eyes. Please help by signing this petition for change, so that our local journalism can retain some semblance of integrity and honesty, and trustworthiness. Please sign this petition to demand that Frank Somerville be reinstated.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

By Eugenia C. South, October 8, 2021

Dr. South is an assistant professor of emergency medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and faculty director of the Urban Health Lab.

PHILADELPHIA — Until a Black man turns 45, his most likely cause of death is homicide. After each such violent death, traumatic shock waves pierce through family and friends. Whole neighborhoods suffer. In some communities with high rates of violent crime, babies are more likely to be born early, children are more likely to struggle in school, and adults are more likely to report being depressed, as well as face increased risk of heart disease.

A recent spike in violent crime in cities across the country has pushed the Biden administration to develop an important federal gun violence prevention strategy. Parents, leaders and activists in Black communities have been fighting against the terror of gun violence for decades. The country is finally catching up to their work.

President Biden’s strategy primarily focuses on bringing resources and services to the people most likely to commit violence and to the people most likely to be victims of that violence. In other words, this strategy focuses on high-risk people. Interventions focused on people who have been tangled in the cycles of violence, such as violence-interrupters programs, are important and necessary.

Missing from the plan, however, is a focused investment in the high-risk places that allow violence to thrive. In large cities, a small number of streets account for an outsize number of violent crimes. Those streets are usually in segregated Black neighborhoods that, because of structural racism, have suffered from decades of disinvestment and physical and economic decline. Dilapidated homes with blown-out windows, blocks with no trees, barren, concrete schoolyards and vacant lots strewn with trash such as used condoms, needles, mattresses and tires often dominate the landscape.

Without changing these physical spaces in which crime occurs, violence-prevention efforts are incomplete. A focused and sustained investment in high-risk places should be a cornerstone in the effort to create safer and healthier communities.

My colleagues Charles Branas and John MacDonald and I have now conducted two large-scale studies where, instead of randomizing people to receive an intervention — as is typical in science — we randomly chose places to receive an intervention. Randomized controlled trials produce the highest level of unbiased results in research: Large, well-constructed R.C.T.s allow us to confidently say that intervention X causes outcome Y.

In partnership with the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, our team transformed run-down vacant parcels of land by planting new grass and trees, installing low wooden post-and-rail fences around the perimeter and performing regular maintenance. We randomly selected hundreds of lots across Philadelphia to receive either this clean and green intervention, trash cleanup only or no intervention at all.

We found that after both the greening and trash cleanup interventions, gun violence went down significantly. The steepest drop in crime, up to 29 percent, was in the several blocks surrounding vacant lots in neighborhoods whose residents live below the poverty line. This signaled that communities with the highest need may benefit the most from place-based investment. Over 18 months, we analyzed for and did not find any evidence of crime simply being pushed to other parts of the city.

Study participants around both interventions reported feeling safer and therefore went outside more often to socialize with neighbors. People around greened lots reported feeling less depressed. This experiment provided clear evidence that changing neighborhood conditions can improve — and improved — seemingly intractable community and mental health problems.

Next, our team conducted a similar trial where we studied abandoned houses, which often have shattered windows and crumbling facades, and are riddled with trash. We randomly selected houses to receive either a full remediation (adding new doors and windows, cleaning the outside of the house and the yard), a trash-cleanup-only intervention or no intervention at all. Our findings, which are not yet published, demonstrate a clear reduction in weapons violations, gun assaults and shootings as a result of the full remediation.

Other similar interventions have strong evidence toward inclusion in violence prevention efforts. In Cincinnati, for instance, a loss of trees because of pest infestation was associated with a rise in crime. And in Chicago, people living in public housing with more trees in common areas reported less mental fatigue and less aggression than did their counterparts in relatively barren buildings. My team has also demonstrated that structural repairs to heating, plumbing, electrical systems and roofing to the homes of low-income owners were associated with a 21.9 percent drop in total crime, including homicide. The more homes repaired on a block, the higher the impact on crime.

Gun violence is expensive, costing billions of dollars annually. Simple, structural and sustainable changes are often low-cost and high-value interventions. We have demonstrated, for example, that in Philadelphia, for every $1 invested in greening, society saves up to $333 that would have gone toward costs such as medical expenses, policing and incarceration.

Across the country, efforts such as The Conscious Connect in Springfield, Ohio, and the Philly Peace Park, in Philadelphia, both led by Black men, are transforming physical spaces to positively influence physical, mental and social health. Organizations such as these, rooted in and led by the community, should be fully resourced in violence prevention efforts.

The reasons that improving places prevents violent crime are not immediately clear to many. Each time we leave our homes and traverse our neighborhoods, the environment is getting under our skin to influence our physical functioning, our thoughts, our behaviors and our interactions. This often happens without our conscious awareness.

A resident of West Philadelphia, a predominantly Black neighborhood, crystallized the connection between place and people in a qualitative study I conducted to better understand how people perceived the links between vacant land and health. The person said: “It makes me feel not important. Like I think that your surroundings, like your environment, affects your mood, it affects your train of thought, your thought process, your emotions. And seeing vacant lots and abandoned buildings, to me that’s a sign of neglect. So I feel neglected.”

I often think about this astute observation after I care for shooting victims in the trauma bay of my emergency department. Especially for those young Black men whose voices I never get to hear and whose names I never know, I wonder: What if we, as a country, made intentional decisions to invest in them and their neighborhoods? Instead of dying, would they flourish?

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Some poorer countries are paying more and waiting longer for the company’s vaccine than the wealthy — if they have access at all.

By Rebecca Robbins, Oct. 9, 2021

A Moderna Covid-19 vaccination in Nairobi, Kenya, a middle-income country where the United States has donated doses. Credit...Simon Maina/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

Moderna, whose coronavirus vaccine appears to be the world’s best defense against Covid-19, has been supplying its shots almost exclusively to wealthy nations, keeping poorer countries waiting and earning billions in profit.

After developing a breakthrough vaccine with the financial and scientific support of the U.S. government, Moderna has shipped a greater share of its doses to wealthy countries than any other vaccine manufacturer, according to Airfinity, a data firm that tracks vaccine shipments.

About one million doses of Moderna’s vaccine have gone to countries that the World Bank classifies as low income. By contrast, 8.4 million Pfizer doses and about 25 million single-shot Johnson & Johnson doses have gone to those countries.

Of the handful of middle-income countries that have reached deals to buy Moderna’s shots, most have not yet received any doses, and at least three have had to pay more than the United States or European Union did, according to government officials in those countries.

Thailand and Colombia are paying a premium. Botswana’s doses are late. Tunisia couldn’t get in touch with Moderna.

Unlike Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca, which have diverse rosters of drugs and other products, Moderna sells only the Covid vaccine. The Massachusetts company’s future hinges on the commercial success of its vaccine.

“They are behaving as if they have absolutely no responsibility beyond maximizing the return on investment,” said Dr. Tom Frieden, a former head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Moderna executives have said that they are doing all they can to make as many doses as possible as quickly as possible but that their production capacity remains limited. All of the doses they produce this year are filling existing orders from governments like the European Union.

Even so, the Biden administration has grown increasingly frustrated with Moderna for not making its vaccine more available to poorer countries, two senior administration officials said. The administration has been pressing Moderna executives to increase production at U.S. plants and to license the company’s technology to overseas manufacturers that could make doses for foreign markets.

Moderna is now scrambling to defend itself against accusations that it is putting a priority on the rich.

On Friday, after The New York Times sent detailed questions about how few poor countries had been given access to Moderna’s vaccine, the company announced that it was “currently investing” to increase its output so it could deliver one billion doses to poorer countries in 2022. The company also said this past week that it would open a factory in Africa, without specifying when.

Moderna executives have been talking with the Biden administration about selling low-cost doses to the federal government, which would donate them to poorer countries, as Pfizer has agreed to do, the two senior officials said. The negotiations are continuing.

In an interview on Friday, Moderna’s chief executive, Stéphane Bancel, said “it is sad” that his company’s vaccine had not reached more people in poorer countries but that the situation was out of his control.

He said that Moderna tried and failed last year to get governments to kick in money to expand the company’s scant production capacity and that the company decides how much to charge based on factors including how many doses are ordered and how wealthy a country is. (A Moderna spokeswoman disputed Airfinity’s calculation that the company had provided 900,000 doses to low-income countries, but she didn’t provide an alternate figure.)

Nearly a year after Western countries began sprinting to vaccinate their populations, the focus in recent months has shifted to the severe vaccine shortages in many parts of the world. Dozens of poorer countries, mostly in Africa and the Middle East, had vaccinated less than 10 percent of their populations as of Sept. 30.

In August, for example, Johnson & Johnson faced rebukes from the director general of the World Health Organization and public health activists after The Times reported that doses of that shot produced in South Africa were being exported to wealthier countries.

Biden administration officials are especially frustrated with what they see as Moderna’s lack of cooperation, because the U.S. government has provided the company with critical assistance.

Scientists at the National Institutes of Health worked with the company to develop the vaccine. The United States kicked in $1.3 billion for clinical trials and other research. And in August 2020, the government agreed to preorder $1.5 billion of the vaccine, guaranteeing that Moderna would have a market for what was an unproven product.

While clinical trials last year found that the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines were similarly effective, more recent studies suggest that Moderna’s shot is superior. It offers longer-lasting protection and is easier to transport and store.

Moderna’s shot is “essentially the premium vaccine,” said Karen Andersen, an industry analyst at Morningstar. “They’re in a position where they probably don’t need to sacrifice too much on pricing in a lot of these deals.”

There is limited public information about the deals that Moderna has struck with individual governments. Of the 22 countries, plus the European Union, to which Moderna and its distributors have reported selling the shots, none are low income, and only the Philippines is classified as lower middle income. (Six are upper middle income.)

Pfizer, by comparison, said it had agreed to sell its vaccine at discounted prices to 12 upper-middle-income countries, five lower-middle-income governments and one poor country, Rwanda. (Tunisia, for example, is paying about $7 per dose.)

Only a handful of governments have disclosed how much they’re paying for Moderna doses. The United States paid $15 to $16.50 for each shot, on top of the $1.3 billion the government gave Moderna to develop its vaccine. The European Union has paid $22.60 to $25.50 for its Moderna doses.

Botswana, Thailand and Colombia, which the World Bank classifies as upper-middle-income countries, have said they are paying $27 to $30 per Moderna dose.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

By Alex Press, October 8, 2021

Ms. Press is a staff writer at Jacobin magazine and the host of Primer, a podcast about Amazon.

In 2015, Cutter Ray Palacios, an actor from Texas, moved to Los Angeles. While auditioning for roles, he found himself working primarily as a production assistant (P.A.), a job that can entail transporting actors to and from set, moving equipment, sorting mail, and running errands for producers or other members of the crew.

Most P.A.s are not unionized. They are some of the most poorly paid people in the television and film industry: Mr. Palacios was making minimum wage, and for a while he was homeless and living in his car.

“You aren’t allowed to sit down as a P.A.,” he told me. Mr. Palacios considers himself lucky because his show treated him “like family.” But he also says that he used to “call 10-1” — the code to use the bathroom — so he “could sit on the toilet for a few minutes.”

After about a year, Mr. Palacios was approached by another crew member about joining the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (I.A.T.S.E.). The union represents “below the line” crew members — the cinematographers, grips, hair stylists, costumers and editors whose work is critical to production even if they don’t get top billing on movie posters. “The guy who approached me said, ‘You have a really strong work ethic. How would you feel about making more money with benefits?’” Mr. Palacios told me.

Mr. Palacios joined I.A.T.S.E. Local 80. He began working in craft services, assisting skilled technicians on set. The higher wages and benefits were an improvement over his time as a P.A., but there was a downside: He went from being someone with a social life to only being friends with people at work. “Once you’re on to the next show, they aren’t your friends anymore, because you’re on to the next job,” he said.

On set, if production falls behind, workdays are extended. By Friday, shifts can bleed into Saturday, leading to “Fraturdays,” as they’re known in the industry. And producers can call workers back in as early as 2 a.m. on Mondays. Twelve and 14-hour days are customary, and 20-hour days are not unheard of; studios can choose to pay paltry “meal penalties” to workers rather than allow them a break for lunch. Many workers fear falling asleep at the wheel on their way home. Such all-consuming labor conditions are now being negotiated as Mr. Palacios’s trade union prepares for a possible strike.