https://www.youthvsapocalypse.org

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

To: U.S. Senate, U.S. House of Representatives

End Legal Slavery in U.S. Prisons

Sign Petition at:

https://diy.rootsaction.org/petitions/end-legal-slavery-in-u-s-prisons

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

On the anniversary of the 26th of July Movement’s founding, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research launches the online exhibition, Let Cuba Live. 80 artists from 19 countries – including notable cartoonists and designers from Cuba – submitted over 100 works in defense of the Cuban Revolution. Together, the exhibition is a visual call for the end to the decades-long US-imposed blockade, whose effects have only deepened during the pandemic. The intentional blocking of remittances and Cuba’s use of global financial institutions have prevented essential food and medicine from entering the country. Together, the images in this exhibition demand: #UnblockCuba #LetCubaLive

Please contact art@thetricontinental.org if you are interested in organising a local exhibition of the exhibition.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Sincere Greetings of Peace:

The “In the Spirit of Mandela Coalition*” invites your participation and endorsement of the planned October 2021 International Tribunal. The Tribunal will be charging the United States government, its states, and specific agencies with human and civil rights violations against Black, Brown, and Indigenous people.

The Tribunal will be charging human and civil rights violations for:

• Racist police killings of Black, Brown, and Indigenous people,

• Hyper incarcerations of Black, Brown, and Indigenous people

• Political incarceration of Civil Rights/National Liberation era revolutionaries and activists, as well as present day activists,

• Environmental racism and its impact on Black, Brown, and Indigenous people,

• Public Health racism and disparities and its impact on Black, Brown, and Indigenous people, and

• Genocide of Black, Brown, and Indigenous people as a result of the historic and systemic charges of all the above.

The legal aspects of the Tribunal will be led by Attorney Nkechi Taifa along with a powerful team of seasoned attorneys from all the above fields. Thirteen jurists, some with international stature, will preside over the 3 days of testimonies. Testimonies will be elicited form impacted victims, expert witnesses, and attorneys with firsthand knowledge of specific incidences raised in the charges/indictment.

The 2021 International Tribunal has a unique set of outcomes and an opportunity to organize on a mass level across many social justice arenas. Upon the verdict, the results of the Tribunal will:

• Codify and publish the content and results of the Tribunal to be offered in High Schools and University curriculums,

• Provide organized, accurate information for reparation initiatives and community and human rights work,

• Strengthen the demand to free all Political Prisoners and establish a Truth and Reconciliation Commission mechanism to lead to their freedom,

• Provide the foundation for civil action in federal and state courts across the United States,

• Present a stronger case, building upon previous and respected human rights initiatives, on the international stage,

• Establish a healthy and viable massive national network of community organizations, activists, clergy, academics, and lawyers concerned with challenging human rights abuses on all levels and enhancing the quality of life for all people, and

• Establish the foundation to build a “Peoples’ Senate” representative of all 50 states, Indigenous Tribes, and major religions.

Endorsements are $25. Your endorsement will add to the volume of support and input vital to ensuring the success of these outcomes moving forward, and to the Tribunal itself. It will be transparently used to immediately move forward with the Tribunal outcomes.

We encourage you to add your name and organization to attend the monthly Tribunal updates and to sign on to one of the Tribunal Committees. (3rd Saturday of each month from 12 noon to 2 PM eastern time). Submit your name by emailing: spiritofmandela1@gmail.com

Please endorse now: http://spiritofmandela.org/endorse/

In solidarity,

Dr. A’isha Mohammad

Sekou Odinga

Matt Meyer

Jihad Abdulmumit

– Coordinating Committee

Created in 2018, In the Spirit of Mandela Coalition is a growing grouping of organizers, academics, clergy, attorneys, and organizations committed to working together against the systemic, historic, and ongoing human rights violations and abuses committed by the USA against Black, Brown, and Indigenous People. The Coalition recognizes and affirms the rich history of diverse and militant freedom fighters Nelson Mandela, Winnie Mandela, Graca Machel Mandela, Rosa Parks, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ella Baker, and many more. It is in their Spirit and affirming their legacy that we work.

https://spiritofmandela.org/campaigns/

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

A BRILLIANT, BRAVE, BLACK POLITICAL JOURNALIST

|

|

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

PLEASE CALL AND EMAIL ON BEHALF OF KEVIN RASHID JOHNSON!

𝘼𝙡𝙡 𝙋2𝙋 𝙤𝙣 𝙩𝙝𝙞𝙨 𝙨𝙚𝙘𝙤𝙣𝙙 𝙙𝙖𝙮 𝙤𝙛 𝘽𝙡𝙖𝙘𝙠 𝘼𝙪𝙜𝙪𝙨𝙩. 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙘𝙤𝙢𝙧𝙖𝙙𝙚 𝙍𝙖𝙨𝙝𝙞𝙙 𝙨𝙩𝙞𝙡𝙡 𝙣𝙚𝙚𝙙𝙨 𝙤𝙪𝙧 𝙖𝙨𝙨𝙞𝙨𝙩𝙖𝙣𝙘𝙚. 𝙄𝙩 𝙞𝙨𝙞𝙢𝙥𝙚𝙧𝙖𝙩𝙞𝙫𝙚 𝙩𝙝𝙖𝙩 𝙘𝙖𝙡𝙡𝙨 𝙖𝙣𝙙 𝙚𝙢𝙖𝙞𝙡𝙨 𝙨𝙩𝙞𝙡𝙡 𝙗𝙚 𝙢𝙖𝙙𝙚 𝙤𝙣 𝙝𝙞𝙨 𝙗𝙚𝙝𝙖𝙡𝙛 𝙩𝙤 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙘𝙤𝙣𝙩𝙖𝙘𝙩𝙨 𝙡𝙞𝙨𝙩𝙚𝙙 𝙗𝙚𝙡𝙤𝙬. 𝙎𝙤𝙢𝙚𝙤𝙣𝙚𝙘𝙤𝙣𝙩𝙖𝙘𝙩𝙚𝙙 𝙢𝙚 𝙚𝙖𝙧𝙡𝙞𝙚𝙧 𝙩𝙤 𝙩𝙚𝙡𝙡 𝙢𝙚 𝙩𝙝𝙖𝙩 𝙍𝙖𝙨𝙝𝙞𝙙'𝙨 𝙘𝙚𝙡𝙡 𝙝𝙖𝙨 𝙗𝙚𝙚𝙣 𝙨𝙚𝙖𝙧𝙘𝙝𝙚𝙙 𝙩𝙬𝙞𝙘𝙚 𝙩𝙝𝙞𝙨 𝙢𝙤𝙧𝙣𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙖𝙨 𝙩𝙝𝙚𝙮𝙗𝙚𝙡𝙞𝙚𝙫𝙚 𝙩𝙝𝙖𝙩 𝙝𝙚 𝙞𝙨 𝙨𝙩𝙞𝙡𝙡 𝙘𝙤𝙢𝙢𝙪𝙣𝙞𝙘𝙖𝙩𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙬𝙞𝙩𝙝 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙤𝙪𝙩𝙨𝙞𝙙𝙚. 𝙏𝙝𝙚 𝙤𝙩𝙝𝙚𝙧 𝙥𝙧𝙞𝙨𝙤𝙣𝙚𝙧𝙨 𝙝𝙖𝙫𝙚 𝙗𝙚𝙚𝙣 𝙞𝙣𝙨𝙩𝙧𝙪𝙘𝙩𝙚𝙙𝙣𝙤𝙩 𝙩𝙤 𝙩𝙖𝙡𝙠 𝙩𝙤 𝙝𝙞𝙢 𝙤𝙧 𝙖𝙨𝙨𝙞𝙨𝙩 𝙝𝙞𝙢 𝙞𝙣 𝙖𝙣𝙮 𝙬𝙖𝙮. 𝙏𝙝𝙚 𝙥𝙞𝙜𝙨 𝙖𝙧𝙚 𝙖𝙩𝙩𝙚𝙢𝙥𝙩𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙩𝙤 𝙨𝙤𝙬 𝙙𝙞𝙫𝙞𝙨𝙞𝙤𝙣 𝙥𝙚𝙧 𝙪𝙨𝙪𝙖𝙡. - Shupavu Wa Kirima

𝙒𝙚 𝙖𝙧𝙚 𝙨𝙩𝙞𝙡𝙡 𝙙𝙚𝙢𝙖𝙣𝙙𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙛𝙤𝙡𝙡𝙤𝙬𝙞𝙣𝙜:

1. 𝘼𝙣 𝙚𝙣𝙙 𝙩𝙤 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙗𝙤𝙜𝙪𝙨 30 𝙙𝙖𝙮 𝙧𝙚𝙨𝙩𝙧𝙞𝙘𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣 𝙛𝙧𝙤𝙢 𝙥𝙝𝙤𝙣𝙚 𝙖𝙣𝙙 𝙚𝙢𝙖𝙞𝙡.

2. 𝘼𝙣 𝙚𝙣𝙙 𝙩𝙤 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙗𝙤𝙜𝙪𝙨 30 𝙙𝙖𝙮 𝙧𝙚𝙨𝙩𝙧𝙞𝙘𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣 𝙛𝙧𝙤𝙢 𝙘𝙤𝙢𝙢𝙞𝙨𝙨𝙖𝙧𝙮 𝙩𝙝𝙖𝙩 𝙥𝙧𝙚𝙫𝙚𝙣𝙩𝙨 𝙍𝙖𝙨𝙝𝙞𝙙 𝙛𝙧𝙤𝙢 𝙤𝙧𝙙𝙚𝙧𝙞𝙣𝙜𝙨𝙩𝙖𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣𝙚𝙧𝙮 𝙬𝙞𝙩𝙝 𝙬𝙝𝙞𝙘𝙝 𝙩𝙤 𝙬𝙧𝙞𝙩𝙚.

3. 𝙏𝙝𝙚 𝙞𝙢𝙢𝙚𝙙𝙞𝙖𝙩𝙚 𝙧𝙚𝙩𝙪𝙧𝙣 𝙤𝙛 𝘼𝙇𝙇 𝙤𝙛 𝙝𝙞𝙨 𝙥𝙧𝙤𝙥𝙚𝙧𝙩𝙮 𝙞𝙣𝙘𝙡𝙪𝙙𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙩𝙝𝙚 $400 𝙩𝙝𝙖𝙩 𝙬𝙖𝙨 𝙤𝙣 𝙝𝙞𝙨 𝙩𝙧𝙪𝙨𝙩 𝙖𝙘𝙘𝙤𝙪𝙣𝙩𝙩𝙝𝙚𝙧𝙚 𝙖𝙩 𝙒𝙑𝘾𝙁 𝙖𝙣𝙙 𝙝𝙞𝙨 𝙡𝙚𝙜𝙖𝙡 𝙥𝙧𝙤𝙥𝙚𝙧𝙩𝙮 𝙬𝙝𝙞𝙘𝙝 𝙬𝙞𝙡𝙡 𝙚𝙣𝙖𝙗𝙡𝙚 𝙝𝙞𝙢 𝙩𝙤 𝙘𝙤𝙣𝙩𝙞𝙣𝙪𝙚 𝙬𝙞𝙩𝙝 𝙝𝙞𝙨 𝙘𝙖𝙨𝙚 𝙖𝙜𝙖𝙞𝙣𝙨𝙩 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙄𝙉𝘿𝙚𝙥𝙖𝙧𝙩𝙢𝙚𝙣𝙩 𝙤𝙛 𝘾𝙤𝙧𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣𝙨. 𝙄𝙛 𝙩𝙝𝙚𝙮 𝙩𝙚𝙡𝙡 𝙮𝙤𝙪 𝙩𝙝𝙖𝙩 𝙝𝙞𝙨 𝙥𝙧𝙤𝙥𝙚𝙧𝙩𝙮 𝙝𝙖𝙨 𝙖𝙡𝙧𝙚𝙖𝙙𝙮 𝙗𝙚𝙚𝙣 𝙨𝙚𝙣𝙩 𝙩𝙝𝙚𝙣 𝙬𝙚 𝙣𝙚𝙚𝙙 𝙩𝙤𝙠𝙣𝙤𝙬 𝙤𝙣 𝙬𝙝𝙖𝙩 𝙙𝙖𝙩𝙚 𝙞𝙩 𝙬𝙖𝙨 𝙨𝙝𝙞𝙥𝙥𝙚𝙙 𝙖𝙣𝙙 𝙬𝙝𝙖𝙩 𝙛𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙡𝙞𝙩𝙮 𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙚𝙞𝙫𝙚𝙙 𝙞𝙩.

𝙏𝙝𝙖𝙣𝙠 𝙮𝙤𝙪 𝙖𝙡𝙡 𝙨𝙤 𝙢𝙪𝙘𝙝 𝙛𝙤𝙧 𝙮𝙤𝙪𝙧 𝙨𝙤𝙡𝙞𝙙𝙖𝙧𝙞𝙩𝙮 𝙖𝙣𝙙 𝙨𝙪𝙥𝙥𝙤𝙧𝙩. 𝙄 𝙖𝙥𝙥𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙞𝙖𝙩𝙚 𝙖𝙡𝙡 𝙤𝙛 𝙮𝙤𝙪. 𝙒𝙚 𝙖𝙧𝙚 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙊𝙉𝙇𝙔𝙡𝙞𝙣𝙚 𝙤𝙛 𝙙𝙚𝙛𝙚𝙣𝙨𝙚 𝙛𝙤𝙧 𝙤𝙪𝙧 𝙞𝙢𝙥𝙧𝙞𝙨𝙤𝙣𝙚𝙙 𝙘𝙤𝙢𝙧𝙖𝙙𝙚𝙨.

* 𝘼𝙣𝙣𝙚𝙩𝙩𝙚 𝘾𝙝𝙖𝙢𝙗𝙚𝙧𝙨-𝙎𝙢𝙞𝙩𝙝, 𝘿𝙞𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙩𝙤𝙧 𝙤𝙛 𝙊𝙝𝙞𝙤 𝘿𝙚𝙥𝙖𝙧𝙩 𝙤𝙛 𝙍𝙚𝙝𝙖𝙗𝙞𝙡𝙞𝙩𝙖𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣 𝙖𝙣𝙙 𝘾𝙤𝙧𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣𝙨 𝙥𝙡𝙚𝙖𝙨𝙚𝙘𝙤𝙣𝙩𝙖𝙘𝙩: 𝙈𝙚𝙡𝙞𝙨𝙨𝙖 𝘼𝙙𝙠𝙞𝙣𝙨 (𝙀𝙭𝙚𝙘𝙪𝙩𝙞𝙫𝙚 𝘼𝙨𝙨𝙞𝙨𝙩𝙖𝙣𝙩) 𝙫𝙞𝙖 𝙚𝙢𝙖𝙞𝙡: 𝙢𝙚𝙡𝙞𝙨𝙨𝙖.𝙖𝙙𝙠𝙞𝙣𝙨@𝙤𝙙𝙧𝙘.𝙨𝙩𝙖𝙩𝙚.𝙤𝙝.𝙪𝙨 𝙤 614-752-1153.

* 𝙍𝙤𝙣𝙖𝙡𝙙 𝙀𝙧𝙙𝙤𝙨, 𝙎𝙤𝙪𝙩𝙝𝙚𝙧𝙣 𝙊𝙝𝙞𝙤 𝘾𝙤𝙧𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣𝙖𝙡 𝙁𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙡𝙞𝙩𝙮, 𝙒𝙖𝙧𝙙𝙚𝙣 (𝙇𝙪𝙘𝙖𝙨𝙫𝙞𝙡𝙡𝙚) (740)259-5544 𝙙𝙧𝙘.𝙨𝙤𝙘𝙛@𝙤𝙙𝙧𝙘.𝙨𝙩𝙖𝙩𝙚.𝙤𝙝𝙞𝙤.𝙪𝙨

*𝙅𝙤𝙨𝙚𝙥𝙝 𝙒𝙖𝙡𝙩𝙚𝙧𝙨, 𝘿𝙚𝙥. 𝘿𝙞𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙩𝙤𝙧 𝙑𝙞𝙧𝙜𝙞𝙣𝙞𝙖 𝘿𝙚𝙥𝙖𝙧𝙩𝙢𝙚𝙣𝙩 𝙊𝙛 𝘾𝙤𝙧𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣𝙨𝙟𝙤𝙨𝙚𝙥𝙝.𝙬𝙖𝙡𝙩𝙚𝙧𝙨@𝙫𝙖𝙙𝙤𝙘.𝙫𝙞𝙧𝙜𝙞𝙣𝙞𝙖.𝙜𝙤𝙫 (𝙋𝙧𝙤𝙭𝙮 𝙛𝙤𝙧 𝙃𝙖𝙧𝙤𝙡𝙙 𝙒. 𝘾𝙡𝙖𝙧𝙠𝙚, 𝘿𝙞𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙩𝙤𝙧 𝙤𝙛 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝘿𝙚𝙥𝙖𝙧𝙩𝙢𝙚𝙣𝙩 𝙤𝙛𝘾𝙤𝙧𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣𝙨) (804)887-7982

*𝙅𝙖𝙢𝙚𝙨 𝙋𝙖𝙧𝙠, 𝙄𝙣𝙩𝙚𝙧𝙨𝙩𝙖𝙩𝙚 𝘾𝙤𝙢𝙥𝙖𝙘𝙩 𝘼𝙙𝙢𝙞𝙣𝙞𝙨𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙩𝙤𝙧 𝙅𝙖𝙢𝙚𝙨.𝙥𝙖𝙧𝙠@𝙫𝙖𝙙𝙤𝙘.𝙫𝙞𝙧𝙜𝙞𝙣𝙞𝙖.𝙜𝙤𝙫

* 𝘾𝙝𝙖𝙧𝙡𝙚𝙣𝙚 𝘽𝙪𝙧𝙠𝙚𝙩𝙩, 𝘿𝙞𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙩𝙤𝙧 𝘿𝙊𝘾 𝙊𝙢𝙗𝙪𝙙𝙨𝙢𝙖𝙣 𝘽𝙪𝙧𝙚𝙖𝙪 (𝙄𝙣𝙙𝙞𝙖𝙣𝙖) (317) 234-3190 𝙊𝙢𝙗𝙪𝙙@𝙞𝙙𝙤𝙖.𝙞𝙣.𝙜𝙤𝙫 𝙍𝙞𝙘𝙝𝙖𝙧𝙙 𝘽𝙧𝙤𝙬𝙣, 𝙒𝙖𝙧𝙙𝙚𝙣 𝙒𝙖𝙗𝙖𝙨𝙝 𝙑𝙖𝙡𝙡𝙚𝙮 𝘾𝙤𝙧𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣𝙖𝙡 𝙁𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙡𝙞𝙩𝙮, 𝙄𝙣𝙙𝙞𝙖𝙣𝙖 (812) 398-5050

* 𝙍𝙞𝙘𝙝𝙖𝙧𝙙 𝘽𝙧𝙤𝙬𝙣, 𝙒𝙖𝙧𝙙𝙚𝙣 𝙒𝙖𝙗𝙖𝙨𝙝 𝙑𝙖𝙡𝙡𝙚𝙮 𝘾𝙤𝙧𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣𝙖𝙡 𝙁𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙡𝙞𝙩𝙮, 𝙄𝙣𝙙𝙞𝙖𝙣𝙖 (812) 398-5050

*𝙘𝙤𝙣𝙩𝙖𝙘𝙩 𝙑𝙞𝙧𝙜𝙞𝙣𝙖 𝘿𝙊𝘾 𝙖𝙪𝙩𝙝𝙤𝙧𝙞𝙩𝙞𝙚𝙨 𝙗𝙚𝙘𝙖𝙪𝙨𝙚 𝙑𝘼 𝙥𝙧𝙞𝙨𝙤𝙣𝙚𝙧𝙨 𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙣𝙨𝙛𝙚𝙧𝙧𝙚𝙙 𝙤𝙣 𝙞𝙣𝙩𝙚𝙧-𝙨𝙩𝙖𝙩𝙚 𝙘𝙤𝙢𝙥𝙖𝙘𝙩𝙨 𝙖𝙧𝙚𝙨𝙪𝙥𝙥𝙤𝙨𝙚𝙙 𝙩𝙤 𝙝𝙖𝙫𝙚 𝙖𝙡𝙡 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙧𝙞𝙜𝙝𝙩𝙨 𝙤𝙛 𝙑𝘼 𝙥𝙧𝙞𝙨𝙤𝙣𝙚𝙧𝙨. 𝙍𝙖𝙨𝙝𝙞𝙙 𝙬𝙖𝙨 𝙤𝙧𝙞𝙜𝙞𝙣𝙖𝙡𝙡𝙮 𝙞𝙣𝙘𝙖𝙧𝙘𝙚𝙧𝙖𝙩𝙚𝙙 𝙞𝙣 𝙑𝘼 𝙗𝙚𝙛𝙤𝙧𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙣𝙨𝙛𝙚𝙧𝙨 𝙩𝙤 𝙊𝙧𝙚𝙜𝙤𝙣, 𝙏𝙚𝙭𝙖𝙨, 𝙁𝙡𝙤𝙧𝙞𝙙𝙖, 𝙄𝙣𝙙𝙞𝙖𝙣𝙖, 𝙖𝙣𝙙 𝙣𝙤𝙬 𝙊𝙝𝙞𝙤.

Our mailing address is:

Kevin Rashid Johnson

D.O.C. #A787991

P.O. Box 45699

Lucasville, OH 45699

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Freedom for Major Tillery! End his Life Imprisonment!

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

Contact: Governor's Press Office

Friday, May 28, 2021

(916) 445-4571

Governor Newsom Announces Clemency Actions, Signs Executive Order for Independent Investigation of Kevin Cooper Case

SACRAMENTO – Governor Gavin Newsom today announced that he has granted 14 pardons, 13 commutations and 8 medical reprieves. In addition, the Governor signed an executive order to launch an independent investigation of death row inmate Kevin Cooper’s case as part of the evaluation of Cooper’s application for clemency.

The investigation will review trial and appellate records in the case, the facts underlying the conviction and all available evidence, including the results of the recently conducted DNA tests previously ordered by the Governor to examine additional evidence in the case using the latest, most scientifically reliable forensic testing.

The text of the Governor’s executive order can be found here:

https://www.gov.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/5.28.21-EO-N-06-21.pdf

The California Constitution gives the Governor the authority to grant executive clemency in the form of a pardon, commutation or reprieve. These clemency grants recognize the applicants’ subsequent efforts in self-development or the existence of a medical exigency. They do not forgive or minimize the harm caused.

The Governor regards clemency as an important part of the criminal justice system that can incentivize accountability and rehabilitation, increase public safety by removing counterproductive barriers to successful reentry, correct unjust results in the legal system and address the health needs of incarcerated people with high medical risks.

A pardon may remove counterproductive barriers to employment and public service, restore civic rights and responsibilities and prevent unjust collateral consequences of conviction, such as deportation and permanent family separation. A pardon does not expunge or erase a conviction.

A commutation modifies a sentence, making an incarcerated person eligible for an earlier release or allowing them to go before the Board of Parole Hearings for a hearing at which Parole Commissioners determine whether the individual is suitable for release.

A reprieve allows individuals classified by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation as high medical risk to serve their sentences in appropriate alternative placements in the community consistent with public health and public safety.

The Governor weighs numerous factors in his review of clemency applications, including an applicant’s self-development and conduct since the offense, whether the grant is consistent with public safety and in the interest of justice, and the impact of a grant on the community, including crime victims and survivors.

While in office, Governor Newsom has granted a total of 86 pardons, 92 commutations and 28 reprieves.

The Governor’s Office encourages victims, survivors, and witnesses to register with CDCR’s Office of Victims and Survivors Rights and Services to receive information about an incarcerated person’s status. For general Information about victim services, to learn about victim-offender dialogues, or to register or update a registration confidentially, please visit:

www.cdcr.ca.gov/Victim_Services/ or call 1-877-256-6877 (toll free).

Copies of the gubernatorial clemency certificates announced today can be found here:

https://www.gov.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/5.28.21-Clemency-certs.pdf

Additional information on executive clemency can be found here:

https://www.gov.ca.gov/clemency/

###

I don’t usually do this. This is discussing my self. I find it far more interesting to tell the stories of other, the revolving globe on which we dwell and the stories spawn by the fragile human condition and the struggles of humanity for liberation.

But I digress, uncomfortably.

This commentary is about the commentator.

Several weeks ago I underwent a medical procedure known as open heart surgery, a double bypass after it was learned that two vessels beating through my heart has significant blockages that impaired heart function.

This impairment was fixed by extremely well trained and young cardiologist who had extensive experience in this intricate surgical procedure.

I tell you I had no clue whatsoever that I suffered from such disease. Now to be perfectly honest, I feel fine.

Indeed, I feel more energetic than usual!

I thank you all, my family and friends, for your love and support.

Onwards to freedom with all my heart.

—Mumia Abu-Jamal

Questions and comments may be sent to: info@freedomarchives.org

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Resources for Resisting Federal Repression

Since June of 2020, activists have been subjected to an increasingly aggressive crackdown on protests by federal law enforcement. The federal response to the movement for Black Lives has included federal criminal charges for activists, door knocks by federal law enforcement agents, and increased use of federal troops to violently police protests.

The NLG National Office is releasing this resource page for activists who are resisting federal repression. It includes a link to our emergency hotline numbers, as well as our library of Know-Your-Rights materials, our recent federal repression webinar, and a list of some of our recommended resources for activists. We will continue to update this page.

Please visit the NLG Mass Defense Program page for general protest-related legal support hotlines run by NLG chapters.

Emergency Hotlines

If you are contacted by federal law enforcement you should exercise all of your rights. It is always advisable to speak to an attorney before responding to federal authorities.

State and Local Hotlines

If you have been contacted by the FBI or other federal law enforcement, in one of the following areas, you may be able to get help or information from one of these local NLG hotlines for:

- Portland, Oregon: (833) 680-1312

- San Francisco, California: (415) 285-1041 or fbi_hotline@nlgsf.org

- Seattle, Washington: (206) 658-7963

National Hotline

If you are located in an area with no hotline, you can call the following number:

Know Your Rights Materials

The NLG maintains a library of basic Know-Your-Rights guides.

- Know Your Rights During Covid-19

- You Have The Right To Remain Silent: A Know Your Rights Guide for Encounters with Law Enforcement

- Operation Backfire: For Environmental and Animal Rights Activists

WEBINAR: Federal Repression of Activists & Their Lawyers: Legal & Ethical Strategies to Defend Our Movements: presented by NLG-NYC and NLG National Office

We also recommend the following resources:

Center for Constitutional Rights

Civil Liberties Defense Center

- Grand Juries: Slideshow

Grand Jury Resistance Project

Katya Komisaruk

Movement for Black Lives Legal Resources

Tilted Scales Collective

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Recent history suggests that it is foolish for Western powers to fight wars in other people’s lands and that the U.S. intervention was almost certainly doomed from the start.

By Adam Nossiter, Aug. 21, 2021

A soldier carrying his gear preparing to leave a base in Kunduz in 2011. Credit...Damon Winter/The New York Times

It was 8 a.m. and the sleepy Afghan sergeant stood at what he called the front line, one month before the city of Kunduz fell to the Taliban. An unspoken agreement protected both sides. There would be no shooting.

That was the nature of the strange war the Afghans just fought, and lost, with the Taliban.

President Biden and his advisers say the Afghan military’s total collapse proved its unworthiness, vindicating the American pullout. But the extraordinary melting away of government and army, and the bloodless transition in most places so far, point to something more fundamental.

The war the Americans thought they were fighting against the Taliban was not the war their Afghan allies were fighting. That made the American war, like other such neocolonialist adventures, most likely doomed from the start.

Recent history shows it is foolish for Western powers to fight wars in other people’s lands, despite the temptations. Homegrown insurgencies, though seemingly outmatched in money, technology, arms, air power and the rest, are often better motivated, have a constant stream of new recruits, and often draw sustenance from just over the border.

Outside powers are fighting one war as visitors — occupiers — and their erstwhile allies who actually live there, something entirely different. In Afghanistan, it was not good versus evil, as the Americans saw it, but neighbor against neighbor.

When it comes to guerrilla war, Mao once described the relationship that should exist between a people and troops. “The former may be likened to water,” he wrote, “the latter to the fish who inhabit it.”

And when it came to Afghanistan, the Americans were a fish out of water. Just as the Russians had been in the 1980s. Just as the Americans were in Vietnam in the 1960s. And as the French were in Algeria in the 1950s. And the Portuguese during their futile attempts to keep their African colonies in the ’60s and ’70s. And the Israelis during their occupation of southern Lebanon in the ’80s.

Each time the intervening power in all these places announced that the homegrown insurgency had been definitively beaten, or that a corner had been turned, smoldering embers led to new conflagrations.

The Americans thought they had defeated the Taliban by the end of 2001. They were no longer a concern. But the result was actually far more ambiguous.

“Most had essentially melted away, and we weren’t sure where they’d gone,” wrote Brig. Gen. Stanley McChrystal, as quoted by the historian Carter Malkasian in a new book, “The American War in Afghanistan.”

In fact, the Taliban were never actually beaten. Many had been killed by the Americans, but the rest simply faded into the mountains and villages, or across the border into Pakistan, which has succored the movement since its inception.

By 2006, they had reconstituted sufficiently to launch a major offensive. The end of the story played out in the grim and foreordained American humiliation that unfolded over the past week — the consecration of the U.S. military loss.

“In the long run all colonial wars are lost,” the historian of Portugal’s misadventures in Africa, Patrick Chabal, wrote 20 years ago, just as the Americans were becoming fatally embroiled in Afghanistan.

The superpower’s two-decade entanglement and ultimate defeat was all the more surprising in that the America of the decades preceding the millennium had been suffused with talk of the supposed “lessons” of Vietnam.

The dominant one was enunciated by the former majority leader of the Senate, Mike Mansfield, in the late 1970s: “The cost was 55,000 dead, 303,000 wounded, $150 billion,” Mansfield told a radio interviewer. “It was unnecessary, uncalled-for, it wasn’t tied to our security or a vital interest. It was just a misadventure in a part of the world which we should have kept our nose out of.”

Long before, at the very beginning of the “misadventure,” in 1961, President John F. Kennedy had been warned off Vietnam by no less an authority than Charles de Gaulle. “I predict that you will sink step by step into a bottomless military and political quagmire, however much you spend in men and money,” de Gaulle, the French president, later recalled telling Kennedy.

The American ignored him. In words that foreshadowed both the Vietnam and Afghan debacles, de Gaulle warned Kennedy: “Even if you find local leaders who in their own interests are prepared to obey you, the people will not agree to it, and indeed do not want you.”

By 1968, American generals were arguing that the North Vietnamese had been “whipped,” as one put it. The problem was, the enemy refused to recognize that it had been defeated, and went right on fighting, as the foreign policy analysts James Chace and David Fromkin observed in the mid-1980s. The Americans’ South Vietnamese ally, meanwhile, was corrupt and had little popular support.

The same unholy trinity of realities — boastful generals, an unbowed enemy, a feeble ally — could have been observed at all points during the U.S. engagement in Afghanistan.

Kennedy should have listened to de Gaulle. The French president, unlike his American counterparts then and later, distrusted the generals and would not listen to their blandishments, despite being France’s premier military hero.

He was at that moment extricating France from a brutal eight-year colonial war in Algeria, against the fervent wishes of his top officers and the European settlers there who wanted to maintain the more than century-old colonial rule. His generals argued, rightly, that the interior Algerian guerrilla resistance had been largely smashed.

But de Gaulle had the wisdom to see that the fight was not over.

Massed at Algeria’s borders was what the insurgents called the “army of the frontiers,” later the Army of National Liberation, or A.L.N., which became today’s A.N.P., or National People’s Army, still the dominant element in Algerian political life.

“What motivated de Gaulle was they still had an army on the frontiers,” said Benjamin Stora, the leading historian of the Franco-Algerian relationship. “So the situation was frozen, militarily. De Gaulle’s reasoning was, if we maintain the status quo, we lose a lot.” He pulled the French out in a decision that still torments them.

The A.L.N. chief, later Algeria’s most important post-independence leader, Houari Boumediène, incarnated strains in the Algerian revolution — dominating strains — that will be familiar to Taliban watchers: religion and nationalism. The Islamists later turned against him over socialism. But the mass outpouring of popular grief at Boumediène’s funeral in 1978 was genuine.

Boumediène’s hold on the people emanated from his own humble origins and his tenacity against the hated French occupier. Those elements help explain the Taliban’s virtually seamless infiltration across Afghan territory in the weeks and months preceding this week’s final victory.

The United States thought it was helping Afghans fight an avatar of evil, the Taliban, the running mate of international terrorism. That was the American optic and the American war.

But the Afghans, many of them, were not fighting that war. The Taliban are from their towns and villages. Afghanistan, particularly in its urban centers, may have changed over 20 years of American occupation. But the laws the Taliban promoted — repressive policies toward women — were not so different, if they differed at all, from immemorial customs in many of these rural villages, particularly in the Pashtun south.

“There is resistance to girls’ education in many rural communities in Afghanistan,” a Human Rights Watch report noted soberly last year. And outside provincial capitals, even in the north, it is rare to see women not wearing the burqa.

This is why for years the Taliban have been dispensing justice, often brutally, in the areas they have controlled, with the acquiescence — even the acceptance — of the local populations. Disputes over property and cases of petty crime are adjudicated expeditiously, sometimes by religious scholars — and these courts have a reputation for “incorruptibility” compared with the former government’s rotten system, Human Rights Watch wrote.

It is a system focused on punishment, often harsh. And despite the Taliban’s protestations this week of forgiveness for those who served the now defunct Afghan administration, they have not shown anything like tolerance in the past. The group’s system of clandestine prisons, housing large numbers of soldiers and government workers, inspired fear in local populations all over Afghanistan.

The Taliban leader, Mullah Abdul Gani Baradar, was reported to have received an enthusiastic welcome when he returned this week to the southern city of Kandahar, the birthplace of the Taliban. That should be another element of reflection for the superpower which, 20 years ago, felt it had no choice but to respond with its military to the crimes of Sept. 11.

For Mr. Malkasian, the historian who was himself a former adviser to America’s top commander in Afghanistan, there is a lesson from the experience, but it is not necessarily that America should have stayed away.

“If you have to go in, go in with the understanding that you can’t wholly succeed,” he said in an interview. “Don’t go in thinking, you’re going to solve it, or fix it.”

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Last year, more than $200 million was spent on campaigning for a state proposition that ensured workers like Uber and Lyft drivers were considered independent contractors.

By Kate Conger, Aug. 20, 2021

A California judge faulted Proposition 22 on Friday for restricting the State Legislature from making gig workers like Uber and Lyft drivers eligible for workers’ compensation. Credit...Tag Christof for The New York Times

A California law that ensures many gig workers are considered independent contractors, while affording them some limited benefits, is unconstitutional and unenforceable, a California Superior Court judge ruled Friday evening.

The decision is not likely to immediately affect the new law and is certain to face appeals from Uber and other so-called gig economy companies. It reopened the debate about whether drivers for ride-hailing services and delivery couriers are employees who deserve full benefits, or independent contractors who are responsible for their own businesses and benefits.

Last year’s Proposition 22, a ballot initiative backed by Uber, Lyft, DoorDash and other gig economy platforms, carved out a third classification for workers, granting gig workers limited benefits while preventing them from being considered employees of the tech giants. The initiative was approved in November with more than 58 percent of the vote.

But drivers and the Service Employees International Union filed a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of the law. The group argued that Prop. 22 was unconstitutional because it limited the State Legislature’s ability to allow workers to organize and have access to workers’ compensation.

The law also requires a seven-eighths majority for the Legislature to pass any amendments to Prop. 22, a supermajority that was viewed as all but impossible to achieve.

Judge Frank Roesch said in his ruling that Prop. 22 violated California’s Constitution because it restricted the Legislature from making gig workers eligible for workers’ compensation.

“The entirety of Proposition 22 is unenforceable,” he wrote, creating fresh legal upheaval in the long battle over the employment rights of gig workers.

“I think the judge made a very sound decision in finding that Prop. 22 is unconstitutional because it had some unusual provisions in it,” said Veena Dubal, a professor at the University of California’s Hastings College of Law who studies the gig economy and filed a brief in the case supporting the drivers’ position. “It was written in such a comprehensive way to prevent the workers from having access to any rights that the Legislature decided.”

Scott Kronland, a lawyer for the drivers, praised Judge Roesch’s decision. “Our position is that he’s exactly right and that his ruling is going to be upheld on appeal,” Mr. Kronland said.

But the gig economy companies argued that the judge had erred by “ignoring a century’s worth of case law requiring the courts to guard the voters’ right of initiative,” said Geoff Vetter, a spokesman for the Protect App-Based Drivers & Services Coalition, a group that represents gig platforms.

An Uber spokesman said the ruling ignored the majority of California voters who supported Prop. 22. “We will appeal, and we expect to win,” the spokesman, Noah Edwardsen, said. “Meanwhile, Prop. 22 remains in effect, including all of the protections and benefits it provides independent workers across the state.”

Uber and other gig economy companies are pursuing similar legislation in Massachusetts. This month, a coalition of companies filed a ballot proposal that could allow voters in the state to decide next year whether gig workers should be considered independent contractors.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

"What is going on is not simply a warm decade or two in a wandering climate pattern. This is unprecedented," said one climate scientist.

By JAKE JOHNSON, August 20, 2021

This past weekend, researchers at the National Science Foundation's Summit Station observed rainfall at the peak of Greenland's rapidly melting ice sheet for the first time on record—an event driven by warming temperatures.

"This was the third time in less than a decade, and the latest date in the year on record, that the National Science Foundation's Summit Station had above-freezing temperatures and wet snow," the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) said in a press release earlier this week. "There is no previous report of rainfall at this location (72.58°N 38.46°W), which reaches 3,216 meters (10,551 feet) in elevation."

Temperatures at the summit of the ice sheet rose above freezing at around 5:00 am local time on Saturday, "and the rain event began at the same time," NSIDC noted. "For the next several hours, rain fell and water droplets were seen on surfaces near the camp as reported by on-station observers."

The anomalous rainfall at the ice sheet's peak marked the start of a three-day period during which "above-freezing temperatures and rainfall were widespread to the south and west of Greenland... with exceptional readings from several remote weather stations in the area," said NSIDC. "Total rainfall on the ice sheet was 7 billion tons."

The warmer-than-usual temperatures caused significant melting of the ice sheet, with melt extent peaking at 337,000 square miles on August 14.

"Warm conditions and the late-season timing of the three-day melt event coupled with the rainfall led to both high melting and high runoff volumes to the ocean," NSIDC observed. "On August 15 2021, the surface mass lost was seven times above the mid-August average... At this point in the season, large areas of bare ice exist along much of the southwestern and northern coastal areas, with no ability to absorb the melt or rainfall. Therefore, the accumulated water on the surface flows downhill and eventually into the ocean."

Ted Scambos, a senior research scientist at the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences at the University of Colorado at Boulder, told the Washington Post on Thursday that while the three-day melting event "by itself does not have a huge impact," it is "indicative of the increasing extent, duration, and intensity of melting on Greenland."

"Like the heat wave in the [U.S. Pacific] northwest, it’s something that's hard to imagine without the influence of global climate change," said Scambos. "Greenland, like the rest of the world, is changing. We now see three melting events in a decade in Greenland—and before 1990, that happened about once every 150 years. And now rainfall: in an area where rain never fell.”

In a landmark report released earlier this month, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concluded that "it is very likely that human influence has contributed to the observed surface melting of the Greenland ice sheet over the past two decades."

In July—which the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration recently deemed the hottest month ever recorded on Earth—a heat wave in Greenland caused enough melting to cover the entire state of Florida with two inches of water.

"What is going on is not simply a warm decade or two in a wandering climate pattern," Scambos told CNN in response to the rainfall at the ice sheet's summit. "This is unprecedented."

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Two new books, Edith Widder’s “Below the Edge of Darkness” and Helen Scales’s “The Brilliant Abyss,” explore the darkest reaches and all that glows there.

By Robert Moor, August 20, 2021

In the deep sea, it is always night and it is always snowing. A shower of so-called marine snow — made up of pale flecks of dead flesh, plants, sand, soot, dust and excreta — sifts down from the world above. When it strikes the seafloor, or when it is disturbed, it will sometimes light up, a phenomenon known, wonderfully, as “snow shine.” Vampire squids, umbrella-shaped beings with skin the color of persimmons, float around collecting this luminous substance into tiny snowballs, which they calmly eat. They are not alone in this habit. Most deep-sea creatures eat snow, or they eat the snow eaters.

Until fairly recently, it was widely believed that the deep seas were mostly devoid of life. For centuries, fishermen hauled in deep-sea trawling nets filled with slime, not knowing that these were carcasses. Some animals, adapted to the pressure of the deep, are so delicate that in lighter waters a mere wave of your hand could reduce them to shreds. The myth of the dead deep sea, known as the Abyssus Theory, was disproved by a series of dredging and trawling expeditions in the 19th century, including a German scientific expedition in 1898 that pulled up the first known vampire squid. But the misconception nevertheless lingered. In 1977, a geologist piloting a submersible near the mouth of a hydrothermal vent, and finding it swarming with creatures, asked the research crew up above, “Isn’t the deep ocean supposed to be like a desert?”

The naturalist William Beebe — the man who coined the phrase “marine snow” — famously made a series of early submersible expeditions, ultimately reaching a depth of a half-mile. He returned in a state of astonishment, carrying “the memory of living scenes in a world as strange as that of Mars.” In fact, it was far stranger. (Mars, being a largely dead planet, is by comparison dead boring.) Down there, many creatures are translucent; others are Vantablack. Some are delicate; others have shells of actual iron. Pale violet octopuses — which normally prefer solitude — gather for warmth in cuddle puddles numbering in the hundreds. Sperm-shaped creatures called giant larvaceans live within a self-constructed cloud of mucous many feet wide, equipped with gorgeously vaulted, wing-shaped chambers designed to filter out food. (Forget Calatrava; not even Calvino could imagine a house as mind-bendingly lovely as these giant gobs of goo.)

And nearly all of them — the fish, the squids, the shrimp — glow.

I know all this because, on a recent trip to Fire Island, I read a pair of new books about the deep sea. Lying on the hot sand, I plunged my head into the chilly darkness of an alien world. It was thrilling, and — for a variety of reasons — more than a little terrifying.

The first (and most gripping) book I read was “Below the Edge of Darkness,” by an oceanographer named Edith Widder. The title is derived from the suboceanic border of the Twilight Zone, where light is dim, and the Midnight Zone, where light is nil. (“I could never again use the word black with any conviction,” wrote Beebe, after reaching the edge of the Midnight Zone.) But darkness — in the optical, not maudlin, sense — is also the organizing theme of Widder’s memoir.

A tomboy who dreamed of “swashbuckling” adventures, Widder broke her back climbing a tree around age 9. (She blames the frilly Sunday school dress her parents made her wear that day). In college, she decided to undergo surgery to repair her spine, but the operation went awry; for reasons unknown, her blood began clotting spontaneously, and she awoke “flipping around like a fish on a dock while hemorrhaging nearly everywhere.” She had to be resuscitated three times; at one point, she felt her mind leave her body. When she awoke again, blood had seeped into her eyeballs, and she was almost fully blind. During a long and painful convalescence, her sight gradually returned, and, with it, a newfound appreciation for the magic of light. “My obsession with bioluminescence grew out of my brush with blindness,” she writes. In truth, her path was somewhat less narratively satisfying; she originally set out to become a neurobiologist. But what began as a short stint in a lab studying bioluminescent dinoflagellates — a way to pass time and earn cash while her husband finished his degree — led to a career change and a lifelong fascination.

She grew to believe the phenomenon of “living light” is “the most important thing happening in the ocean.” And since the deep sea makes up more than 95 percent of the earth’s habitable space, in a sense, that also makes it the most important thing happening on the planet.

All kinds of creatures luminesce in all kinds of ways, for all kinds of reasons. Light is used as a lure, a weapon, a warning, a deception, a beacon and a sexual turn-on. Individual bacteria probably evolved to glow because it minimizes the radiation from UV light, which can damage DNA; en masse, their glow helps attract predators. (Bacteria, unlike fish, want to end up in a gut.) Anglerfish grow light bulbs that dangle from their foreheads, which they use as bait. When threatened, sea cucumbers will shuck a glowing layer of skin, creating spectral apparitions of themselves as a decoy. Some species spray their attackers with a burst of glittering light — fire-breathing shrimp, fire-shooting squids, shining tubeshoulder fish. In the higher reaches of the deep sea, where there is nowhere to hide, many fish have evolved to emit blue light, a trait known as counterillumination. The most numerous vertebrate on earth, the bristlemouth fish, uses this trick to blend into the sea itself.

Widder originally used submersibles to reach the twilight zone. A few mishaps with leaky valves nearly killed her. (At a certain depth, a terrifying feedback loop sets in: The water streaming in makes the vessel heavier, which means the vessel sinks deeper, which means more water pressure, which means more water streams in, ad infinitum, until the vessel either implodes or the diver drowns.) She began experiencing suffocation nightmares; once she awoke to find herself clawing at the bottom of the bunk above her, convinced it was a coffin lid. “Lousy sleep. Keep having dreams of entrapment and drowning,” she stoically wrote in her diary. Understandably, she shifted some of her attention to developing cameras (“new technological eyes,” she calls them) and lures, which could dive in her stead.

Perhaps her most successful co-invention was a glowing synthetic jellyfish known as the “E-jelly.” Using this lifelike bait, she managed to capture the first video of a giant squid in its natural habitat (which she deems “the holy grail” of her field of research). Her description of these excursions, and the resulting discoveries, provides a thrilling blend of hard science and high adventure.

Widder’s voice is in turns jaunty, precise and nerdily quippy. She occasionally resorts to cliché (“At that depth, the tiniest leak could create a high-pressure jet that would cut through my flesh like a hot knife through butter”), and her jokes don’t always land. But often the prose glints. In one of my favorite passages in the book, she describes the mating rituals of the anglerfish, those toothy monsters with the dangling headlamps:

“The male anglerfish is much smaller than his female counterpart. He lacks a lure and has no teeth for consuming prey. For many anglerfish species, the male’s only hope for continued existence is as a gigolo. In the unimaginably immense black void of the deep sea, he must somehow locate a potential mate, either visually or by smell, and upon finding her, seal the relationship with an eternal kiss by latching on to her flank, where his flesh fuses with hers. Her bloodstream then grows into his body, providing him with sustenance, in return for which he provides sperm upon demand. This lifetime commitment may sound romantic, but it’s not all hearts, flowers and pillow talk. He’s a bloodsucker and a sperm bag, and she’s ugly and weighs half a million times more than he does.”

Where Widder unfortunately falls short is in the final pages of the book, where she briefly addresses environmental threats to the ocean. She hews to the old and, increasingly, outdated maxim that alarmism will cause the public to shut down rather than perk up. Given the pending cascade of catastrophes that climate change threatens to inflict on the oceans (perhaps nowhere more so than on the deep sea, which studies show will warm faster than the surface), her cheery contention that a combination of optimism, exploration and education will solve the ocean’s problems rings hollow.

Thankfully, another new book more than makes up for this shortfall. “The Brilliant Abyss,” Helen Scales’s sweeping survey of the seafloor, is brave enough to risk a darker and, in some ways, more satisfying tone.

The deep sea that Scales portrays is a largely unseen realm that is continually being plundered, often by people who have little notion of what they are destroying. Between the two writers, Scales is the more graceful storyteller, but Widder has (by far) the more compelling story to tell. Indeed, Scales’s conceit — of traveling aboard a research vessel for a couple of weeks in the Gulf of Mexico — feels a bit thin, and not just by comparison to Widder’s heroics. She never physically ventures into the abyss, as Widder did, and as a fellow science writer, James Nestor, did in his excellent 2014 book, “Deep.” (In one nape-tingling chapter, he describes traveling to a depth of 2,500 feet in “a homemade, unlicensed submarine” cobbled together by a New Jersey eccentric.) But for its shortcomings, “The Brilliant Abyss” has many virtues. Scales’s great gift is for transmuting our awe at the wonders of the deep sea into a kind of quiet rage that they could soon be no more.

In one of the book’s most appalling chapters, she describes the sad fate of the orange roughy, a remarkably slow-growing, deep-dwelling fish. Formerly known as the slimehead, the species was rebranded in the 1970s to better appeal to consumers. Demand spiked, and a “gold rush mentality” ensued. Trawl nets were dragged along the seafloor, hauling up not just roughies, but also the wreckage of coral reefs — “millennia-old, animal-grown forests” — which were tossed overboard as bycatch. Predictably, the fish population quickly collapsed, and they — and the ecosystems that were razed to catch them — have yet to return to their former vigor.

Scales excoriates not just the killers of the orange roughy, but the entire industry. Globally, she writes, deep-sea trawlers pull in profits of just $60 million a year, and yet they receive subsidies of $152 million. “If it costs so much, provides so little food, and reaps such huge ecological damage, the glaring question is, why trawl for fish in the deep at all?” Scales asks. Some have begun calling for a global ban on deep-sea trawling. Scales goes a step further. Looking into the future, where the mining of rare earth metals and the dumping of carbon in the deep sea promise to become lucrative (if destructive) industries, she urges us to err on the side of preservation: no deep-sea mining, fishing, oil drilling or extraction of any kind. The deep, she argues, is too vulnerable, and too crucial to the working of the planet to blindly ransack. (Among other things, the ocean acts as an enormous carbon sequestration device, one we are determinedly, if inadvertently, breaking.)

She concludes: “If industrialists and powerful states have their way, and the deep is opened up to them, then it raises the ironic and dismal prospect that the deep sea will become empty and lifeless, just as people once thought it was.”

Comparisons are often made between the deep sea and the cosmos. One obvious difference between the two is that the abyss below teems with life. Another is that, unlike the stars, the twinkling lights of the deep sea are hidden from view. “As soon as you stop thinking about it, the deep can so easily vanish out of mind,” Scales warns. She and Widder have worked hard to bring the abyss to light. It is our duty, as clumsy land-bound dwellers of a water planet, to look, and to remember.

Robert Moor is the author of “On Trails: An Exploration.”

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

"If Nabisco can rake in billions of dollars in corporate profits, they can afford to treat their workers with dignity and respect."

By Brett Wilkins, August 20, 2021

https://www.commondreams.org/news/2021/08/20/no-contracts-no-snacks-nabisco-workers-strike-across-us?

Various Nabisco products are on display on a supermarket shelf. (Photo: Jeffrey Greenberg/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Employees at Nabisco's flagship plant in Chicago walked off the job Thursday, joining workers at three of the leading snack maker's other U.S. plants who are demanding better working conditions, an end to foreign outsourcing, and the withdrawal of a company plan that would scrap the company's current guaranteed overtime pay system.

The strike began August 10 when around 200 members of the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers, and Grain Millers' (BCTGM) International Union Local 364 walked out of a Nabisco factory in Portland, Oregon that makes Oreo and Chips Ahoy! cookies, as well as Ritz, Premium saltines, and other crackers.

Workers at Nabisco plants in Aurora, Colorado and Richmond, Virginia followed suit, saying they planned to strike until Nabisco's parent company, multinational confectionery corporation Mondelez International, agrees to negotiate a new contract. The most recent agreement expired in May.

With U.S. snack consumption rising during the pandemic, Mondelez's 2020 revenue increased to $26.6 billion, according to Chicago Business Journal, with profits of $3.6 billion and a 6% annual increase in share price. Dirk Van de Put, Mondelez's new CEO, could earn more than $17 million in compensation, plus a $38 million one-time windfall, this year.

Meanwhile, Nabisco workers have been forced to work 12 to 16 hour shifts, six to seven days a week, during the pandemic, while the company seeks to eliminate overtime pay by altering employee schedules so that weekend shifts become part of the 40-hour work week. Workers are also rejecting a Mondelez proposal to create different employee health plans under which new hires would pay more, including deductibles—which do not exist under the current system.

Nabisco workers stress that they are not asking for more pay or benefits.

"This fight is about maintaining what we already have," Mike Burlingham, vice president of BCTGM Local 364 in Portland, told Today. "During the pandemic, we all were putting in a lot of hours, demand was higher, people were at home, and the snack food industry did phenomenally well. Mondelez made record profits and they want to thank us by closing two of the U.S. bakeries and telling the rest of us we have to take concessions, what kind of thanks is that?"

"We make them a lot of money," added Burlingham. "It's very disheartening. How is that supposed to make us feel?"

Workers say the proposed changes are the latest in a long line of affronts that began in 2016 when Mondelez laid off 600 workers while shutting down half of Nabisco's Chicago production lines and relocating operations to Mexico. In 2018, the company eliminated the pensions of thousands of workers and retirees, and this year over 1,000 jobs were lost when plants in Georgia and New Jersey were shuttered.

"They couldn't care less about us," striker Donna Marks, who has worked 17 years at the Portland plant, said of Mondelez in an interview with nwLaborPress.

"I used to enjoy this job, it used to be like a family to me," Marks told Willamette Week. "Now, they want us to work more and pay us less, and everything that we have, we have because we negotiated. They want to take away what we fought for with no negotiation. They act as if they gave us something."

Rusty Lewis, a striking worker at Nabisco's Aurora distribution center, told Motherboard that workplace conditions have been deteriorating during his 25-year tenure.

"It's gotten worse. It's gotten horrible. Horrible hours," he said. "They don't care about frontline workers. They only care about the almighty dollar. We're tired of getting stepped on and treated like trash. We've had enough."

Mondelez said in a statement that its goal "has been—and continues to be—to bargain in good faith with the BCTGM leadership across our U.S. bakeries and sales distribution facilities to reach new contracts that continue to provide our employees with good wages and competitive benefits, including quality, affordable healthcare, and [a] company-sponsored Enhanced Thrift Investment 401(k) Plan, while also taking steps to modernize some contract aspects which were written several decades ago."

The strike has drawn solidarity and support from BCTGM workers at Frito-Lay's Topeka, Kansas factory—who ended their nearly seven-week strike on Wednesday—as well as from other unions, activists, politicians, and celebrities.

"I stand in solidarity with BCTGM workers in Oregon, Colorado, and Virginia who are on strike for a fair contract and for decent working conditions," Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) tweeted Wednesday. "If Nabisco can rake in billions of dollars in corporate profits, they can afford to treat their workers with dignity and respect."

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

"Virtually no child's life will be unaffected" by the climate emergency, said the director of UNICEF.

By Julia Conley, August 20, 2021

https://www.commondreams.org/news/2021/08/20/nearly-half-worlds-children-extremely-high-risk-facing-effects-climate-crisis-

A village official evacuates a child from a flooded area following heavy rains in Dazhou in China's southwestern Sichuan province on July 12, 2021. (Photo: STR/AFP via Getty Images)

On Friday, August 20, 2021, the third anniversary of climate campaigner Greta Thunberg's lone protest outside the Swedish Parliament, a global report revealed the scale of risks posed by the climate emergency for the world's children.

The United Nations' agency for children's rights, UNICEF, introduced the first-ever Children's Climate Risk Index, which shows that nearly half of the world's children are at "extremely high risk" for being faced with dangerous effects of the planetary crisis.

"The climate crisis is a child rights crisis," said UNICEF.

About one billion children live in dozens of developing countries that are facing at least three to four climate impacts, including drought, food shortages, extreme heat, and disease, the report, launched in collaboration with Fridays for Future, found.

"For the first time, we have a complete picture of where and how children are vulnerable to climate change, and that picture is almost unimaginably dire," said Henrietta Fore, executive director of UNICEF, in a statement.

Some of the highest-risk countries include India, Nigeria, and the Central African Republic—countries which are among the least responsible for rampant fossil fuel extraction and greenhouse gas emissions contributing to the climate crisis.

"The top 10 countries that are at extremely high risk are only responsible for 0.5% of global emissions," Nick Rees, lead author of the report, told The Guardian.

UNICEF used high-resolution maps of climate impacts as well as maps showing children's vulnerability to poverty, lack of access to clean water, and other factors that make young people less able to survive climate-related catastrophes like extreme weather events.

While nearly half of the world's children are at extreme risk for experiencing multiple effects of the climate crisis firsthand, nearly every child on Earth was found to be at risk for at least one impact, including heat waves and air pollution.

"Virtually no child's life will be unaffected," Fore said.

According to the report, 820 million children—more than one-third—are at risk for experiencing extreme heatwaves like the deadly ones that have affected the United States' Pacific Northwest, Canada, and Western Europe this year. One in seven children are at risk for facing flooding rivers, and two billion are currently highly exposed to air pollution.

Thunberg, who is 18, was among the young climate leaders who wrote the foreward to the report, demanding urgent action by the world's policymakers as she did outside the Swedish Parliament in 2018 and then at weekly Fridays for Future demonstrations that quickly spread across the world, with millions of children and young adults joining.

"Our futures are being destroyed, our rights violated, and our pleas ignored. Instead of going to school or living in a safe home, children are enduring famine, conflict and deadly diseases due to climate and environmental shocks," wrote Thunberg, Adriana Calderón of Mexico, Farzana Faruk Jhumu of Bangladesh, and Eric Njuguna of Kenya. "These shocks are propelling the world's youngest, poorest, and most vulnerable children further into poverty, making it harder for them to recover the next time a cyclone hits, or a wildfire sparks."

The young advocates also published an op-ed in the New York Times on Friday to mark the release of the report.

"The fundamental goal of the adults in any society is to protect their young and do everything they can to leave a better world than the one they inherited," they wrote. "The current generation of adults, and those that came before, are failing at a global scale."

The report calls for children to be included in worldwide policy discussions and decision-making regarding the mitigation of the climate crisis, including the upcoming United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) scheduled for November.

Policymakers attending the conference hope to secure a plan for global net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, mobilize financing from rich countries to help the developing world mitigate the crisis, and finalize regulations to make the Paris climate agreement operational.

"There is still time for countries to commit to preventing the worst, including setting the appropriate carbon budgets to meet Paris targets, and ultimately taking the drastic action required to shift the economy away from fossil fuels," reads the report. "We must acknowledge where we stand, treat climate change like the crisis it is and act with the urgency required to ensure today’s children inherit a liveable planet."

Considering that decisions made at COP26 "will define their future," Fore told The Guardian, "children and young people need to be recognized as the rightful heirs of this planet that we all share."

The report also recommends increasing the resilience and delivery of social services including healthcare, access to clean water, and social safety nets to "mitigate the worst impacts of climate change" and nature-based solutions to the crisis including wetland restoration and ecosystem protection.

UNICEF highlighted some positive recent large-scale changes including the falling cost of renewable energy sources and increased recognition by the financial system of "the risks that a degrading climate poses," leading to divestment from pollution-causing fossil fuel projects.

"One of the biggest reasons for hope is the power of children and young people. In recent years, children and young people have taken to the streets to demand action on climate change, and throughout the Covid-19 pandemic they have continued their protest online," reads the report. "They have revealed the depth of frustration that they feel at this intergenerational form of injustice, as well as their courage and willingness to challenge the status quo, and their role as key stakeholders in addressing the climate crisis."

"Children are not afraid—and nor should they be—to demand that adults do everything they can to protect their future home," said UNICEF.

"Movements of young climate activists will continue to rise, continue to grow and continue to fight for what is right because we have no other choice," said Jhumu, Njuguna, Calderón, and Thunberg in the report. "We must acknowledge where we stand, treat climate change like the crisis it is, and act with the urgency required to ensure today’s children inherit a liveable planet."

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

David Gilbert, who was serving a 75-year sentence for felony murder in the notorious Rockland County crime, will now be eligible for parole.

By Michael Wilson and Jesus Jiménez, Published Aug. 23, 2021, Updated Aug. 24, 2021

In the waning hours of his final day in office, Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo commuted the prison sentence of one of the members of the gang behind the infamous robbery of a Brink’s armored car in 1981 that left two police officers and a guard dead, a politically motivated ambush that continues to reverberate 40 years later.

David Gilbert is serving a 75-years-to-life sentence for his role in the crime as a member of the Weather Underground, which stole $1.6 million in cash from the armored car outside the Nanuet Mall near Nyack, N.Y.

The decision does not mean he will automatically be released from prison. Mr. Gilbert will be granted a parole hearing in the weeks to come, according to Monday’s announcement.

Mr. Gilbert is the second member of the group to seek relief from Mr. Cuomo. In 2016, the governor commuted the 75-year sentence of Judith Clark, praising her “exceptional strides in self-development” as an inmate. Mr. Cuomo’s actions also granted her a parole hearing, and she was eventually released.

Mr. Cuomo cited Mr. Gilbert’s work in AIDS education and prevention while in prison, and as a teacher and law library clerk.

“He has served 40 years of a 75-year sentence, related to an incident in which he was the driver, not the murderer,” Mr. Cuomo wrote on Twitter on Monday evening.

Mr. Gilbert’s upcoming parole hearing follows a campaign for his release that included his son, Chesa Boudin, who was an infant when his mother, Kathy Boudin, and Mr. Gilbert were convicted in the attack, and who in 2019 was elected the district attorney of San Francisco. Ms. Boudin was released in 2003 after receiving a 20-year sentence as part of a plea deal, and went on to become a professor at Columbia University.

“I am overcome with emotion,” Mr. Boudin said in a statement on Monday night. “My heart is bursting, and it also aches for the families of the three victims. Although he never used a gun or intended for anyone to get hurt, my father’s crime caused unspeakable harm and devastated the lives of many separate families. I will continue to keep those families in my heart; I know they can never get their loved ones back.”

Killed in the robbery were Sgt. Edward O’Grady, Officer Waverly Brown and Peter Paige, a Brink's guard. The commutation of Mr. Gilbert’s sentence, like Ms. Clark’s before him, outraged the law enforcement community in Rockland County.

“It’s absurd,” Arthur Keenan Jr., a retired detective with the Nyack Police Department, who was wounded in the shootout, said on Monday. He said Mr. Cuomo “is stabbing all of law enforcement in the back, and when I say all, I’m talking about federal, state, local — all across the whole country — because he’s a traitor.”

In a statement, Ed Day, the Rockland County executive, said that Mr. Cuomo, a Democrat, had “debased himself” and the office of the governor.

“As if victimizing 11 women, including members of his own staff, was not despicable enough, his commutation of the 75-years-to-life sentence of David Gilbert is a further assault on the people of Rockland and New York State,” said Mr. Day, a Republican. “Andrew Cuomo continues to focus on the well-being of murderers rather than the victims of these horrible offenses.”

Also among the five people whose sentences were commuted on Monday — and who, unlike Mr. Gilbert, will all be released from prison without further hearings — was Ulysses Boyd, 66, who was convicted of one count of second-degree murder, and of two counts of second-degree criminal possession of a weapon. Mr. Boyd has served 35 years of a 50-years-to-life sentence for killing Harold Bates during an encounter at a drug house in 1986.

“Times doesn’t go by that I don’t think of Mr. Harold Bates and his family because I still got my family,” he said in a video filmed before the coronavirus outbreak. “I can still see my kids. They don’t have that choice no more.”

Mr. Boyd said he has an enlarged heart and chronic arthritis, and had pneumonia last year.

“When I wake up in the morning, I’m in pain,” Mr. Boyd said in the video. “Basically, I’m just waiting to die.”

Mr. Cuomo also commuted the sentence of Gregory Mingo, 68, who had been the subject of persistent petitions and legal and public appeals disputing his conviction in the 1980 murders of James Parker and Karen Sheets. Mr. Mingo has maintained his innocence, and his case gained notice following the protests for racial justice prompted by the death of George Floyd.

In an online petition that has accumulated 144,000 signatures, Mr. Mingo’s niece, Ava Nemes, wrote that he had been convicted on “thin allegations” that included no physical evidence, and that his defense lawyer had failed to present his alibi. Recently, the CUNY School of Law Defenders Clinic applied for clemency on his behalf.

Mr. Mingo has served nearly 40 years in prison, and Ms. Nemes wrote that his incarceration had shaped her life.

“Uncle Greg missed my birth, but when I was four, my parents moved to Westchester, N.Y., so we could be closer to where he was imprisoned,” she said. “I’ve felt his absence in every milestone of my life since then.”

Mr. Cuomo also commuted the sentences of two other people convicted of murder, according to a news release:

Paul Clark, 59, who was convicted of three counts of second-degree murder and other charges and has served 40 years in prison;

And Robert Ehrenberg, 62, who was convicted of second-degree murder and other charges and has served 28 years in prison.

Mr. Cuomo also pardoned Lawrence Penn, who in 2015 pleaded guilty of falsifying business records.

Grace Ashford contributed reporting.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Officers’ groups say 84-year-old Sundiata Acoli, convicted of murder of New Jersey state trooper, poses no threat to public safety

By Ed Pilkington, August 24, 2021

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/aug/24/black-police-officers-groups-seek-parole-former-black-panther-sundiata-acoli

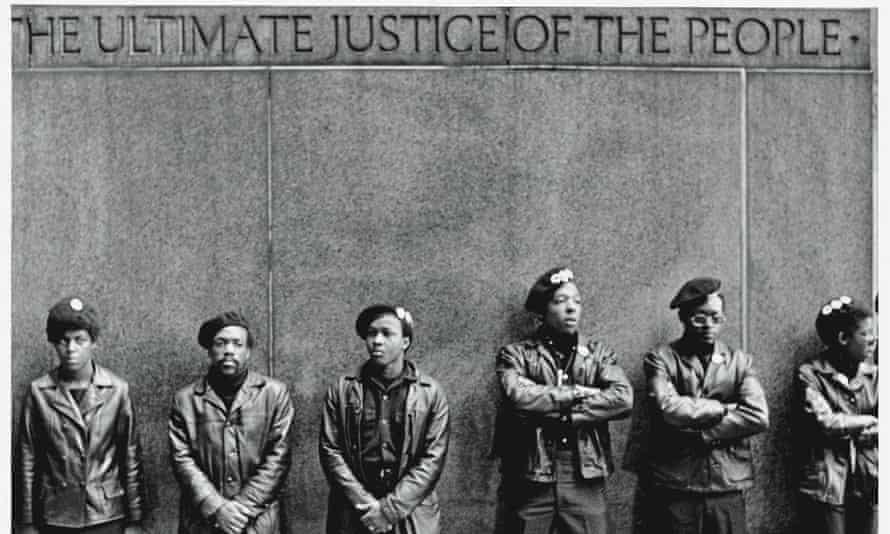

Members of the Black Panthers have received exceptionally long prison sentences. Photograph: David Fenton/Getty Images

A coalition of current and retired Black police officers is calling for the release on parole of Sundiata Acoli, a former Black Panther member who has been incarcerated for 48 years for the 1973 murder of a New Jersey state trooper.

Four Black law enforcement groups have joined forces to press the case for Acoli’s parole almost half a century after he was arrested. In an amicus brief filed with the New Jersey supreme court, they call his continued imprisonment “an affront to racial justice” and accuse the parole board of violating the law by repeatedly refusing to set the prisoner free.

“Mr Acoli has spent more than half of his life in prison cells the size of a parking space, including nearly 20 years as a senior citizen … He should be granted parole,” the groups write.

Acoli is one of at least 11 former members of the Black Panther Party and its armed wing, the Black Liberation Army, who are still in prison for acts of violence committed largely in the late 1960s and 1970s. Many of the prisoners are approaching their half-century behind bars.

At 84, Acoli is the oldest of the former Black radicals still languishing in prison. He contracted Covid-19 last year from his cell in FCI Cumberland in Maryland, and is suffering from physical and mental impairments including gradual deterioration of his memory.

In a written communication with the Guardian, Acoli said that he was struggling with chronic degeneration of his hearing, eyesight, and mental and muscular capacity yet was receiving “little or no medical treatment” in prison.

“I am an 84-year-old man who’s been imprisoned since age 36 for almost 50 years, who now poses a threat not even to a flea, let alone public safety,” he said.

Acoli added: “My sentence is obviously too long. I am rapidly disintegrating before my family and friends’ eyes.”

When asked about the amicus brief, Acoli said: “The Black associations are simply expressing their opinion on what everyone already knows: that it’s time, actually past time, that I should be released.”

The intervention of the Black groups underscores a rift within police officer organizations. Powerful white-dominated law enforcement associations have been at the forefront of the battle to keep former Black Panthers incarcerated for decades.

In Acoli’s case, the New Jersey State Troopers Fraternal Association has called for him to remain “locked up and away from civil society for the rest of his life”.

Acoli, who was born Clark Edward Squire, was given a life sentence in 1974 for the murder of New Jersey state trooper Werner Foerster the previous year. Acoli had been driving along the New Jersey Turnpike together with two other members of the Black Liberation Army, Assata Shakur (born JoAnne Chesimard) and Zayd Malik Shakur (James Costan) when they were stopped by a state trooper, James Harper, over a defective taillight.

In the ensuing melee, shots were fired. Foerster was struck with four bullets and died, and Zayd Malik Shakur was also killed. Harper was wounded, and both Acoli and Assata Shakur were arrested after a police chase.

Shakur escaped and fled to Cuba, where she was granted asylum by the Cuban government. In 2013 she became the first woman to be put on the FBI’s “most wanted terrorists” list, and at age 74 she faces a $2m reward for information leading to her capture.

In the amicus brief, the four Black police officer groups make powerful arguments against Acoli’s continuing imprisonment. They point out that New Jersey has the greatest disparity in the nation between the incarceration rate of Black and white people – a gap of 12 to 1, according to the state’s Criminal Sentencing and Disposition Commission.

Almost two thirds of New Jersey prisoners serving life sentences are Black.

They also point out that prisoners on life sentences, like Acoli, tend to have the lowest recidivism rate of all classes of prisoner – and the rate falls further with age. Yet over the past 40 years the rate of prisoners granted release by the New Jersey parole board has plummeted – from 42% in the 1980s to just 7% between 2012 and 2019.

The Black groups accuse the parole board of obsessively focusing on whether Acoli has changed his radical political views rather than concentrating on the only issue they are required to consider – whether he poses a threat to the public should he be freed. The amicus brief says the board’s approach amounts to “extralegal punishment”.

Acoli first came up for parole in 1993, and on that occasion was not only denied but told he would have to wait another 20 years before he could reapply to the board. In 2014 he came close to walking free when a three-judge panel of the state appeals court ordered his release on grounds he posed no threat at all – only to have that ruling overturned by the state supreme court.

After a further round of parole board and court hearings, he is now appealing again to the New Jersey supreme court, which is expected to consider the case later this year or early next.

The four groups that have jointly written the amicus brief are: the National Association of Blacks in Criminal Justice, Blacks in Law Enforcement of America, the Black Police Experience and the Grand Council of Guardians.

Ronald Hampton, who served for 24 years as a police officer in Washington DC and who is now with Blacks in Law Enforcement of America, said that prolonged prison terms for the former Black Panthers highlighted racial distortions in the criminal justice system. “These long sentences are absurd. The system is meant to rehabilitate – prisoners who complete their sentences should be sent home, but that hasn’t worked for Black folks.”

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

By Catherine Flowers and Mitchell Bernard, Aug. 25, 2021

Catherine Flowers is the founder of the Center for Rural Enterprise and Environmental Justice. She is vice chair of the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Committee. Mitchell Bernard is chief counsel of the Natural Resources Defense Council.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/25/opinion/environmental-racism-wastewater-broken.html

Golden Cosmos

Linda McNeil had barely settled into her newly built home a 20-minute drive from Manhattan when raw sewage first flooded her basement. That was 21 years ago, and the problem has only grown worse. Like others among the predominantly Black population in the city of Mount Vernon, N.Y., Ms. McNeil and her family have spent thousands of dollars on equipment to manually pump out the human waste that routinely backs up from the city’s failing wastewater system and gushes into her toilet, bathtub and sink. For months last winter it happened several times a day.

It’s a vile and all too common assault that inflicts a kind of hygienic hell on more than 1,000 Mount Vernon families each year.

“It takes an emotional toll, mental, physical,” Ms. McNeil said in a July news conference the city held to draw attention to the problem. “The headaches, the smells, the loss of appetite, depression, the lack of sleep. It takes a toll on you.”

Does anyone genuinely believe that what’s happening in Mount Vernon would be happening in one of the richer, predominantly white communities also in Westchester County in the shadow of New York City?

While the conditions in the Mount Vernon example are extreme, they are by no means unique: the nation’s wastewater infrastructure gets a D-plus from the American Society of Civil Engineers. Across much of the country, wastewater infrastructure needs to be repaired or replaced, or is simply overburdened by demands that exceed what it was built to handle.

Mount Vernon is one of scores of cities around the country with an outdated or overtaxed sewage system — in its particular case: century-old pipes of clay that are crumbling with age, woefully inadequate for the city of 67,000, and commonly swamped by even light rain. Its failing wastewater system is in violation of the Clean Water Act, New York state law, administrative orders from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency dating back to 2014 and a federal court order.

The deepest cause of this calamity is decades of underinvestment at the federal level in the nation’s wastewater infrastructure combined with a history of structural racism that has imposed disproportionate environmental hazard and harm on many low-income communities and people of color for far too long.

The good news is that President Biden’s Build Back Better agenda confronts both problems head-on. And Congress has the statutory authority to enact this agenda in full.

The nation’s wastewater management systems are regulated under the 1972 Clean Water Act, which set national standards for handling and treating sewage and other wastewater. The law led to the creation of a revolving fund that provides grants and loans that help localities build and maintain water systems — including the pipes, treatment facilities and other infrastructure to manage wastewater.

For three decades, though, Congress has cut this funding, slashing it to roughly a quarter of its levels in the late 1970s, leaving cities and towns struggling to close the gap.

The wastewater problem has been especially acute in majority Black communities like Mount Vernon. And it shows environmental injustice isn’t limited to Southern areas like Houston and Baton Rouge, La., where industrial waste sites and refineries are concentrated in majority Black neighborhoods. In Oakland, Calif., giant container shipping facilities, and the air pollution they generate, are adjacent to Black and Hispanic communities. And infamously in Flint, Mich., aging lead pipes have contaminated drinking water supplies in the predominantly Black city for years.

Environmental injustice unfortunately has many manifestations, all of them baked into the nation’s social and economic order. It’s an injustice that shows up as redlined urban neighborhoods that get hotter in summer because they lack green spaces. We can see it in rural communities hard hit by toxic landfill sites and raw sewage or coal ash impoundments. We’re beginning to see it in the disproportionate price people of color will pay for climate change.

The latest United Nations report on the climate crisis makes clear the kinds of storms and the flooding we are experiencing now, and the worsening stress water systems can expect, which makes reform evermore urgent. President Biden’s agenda to Build Back Better would increase desperately needed federal funds to help cities cope with a widening wastewater crisis impacting rural and urban areas alike, from Centreville, Ill. to Lowndes County, Ala.

The bipartisan infrastructure bill that recently passed the Senate would make a down payment, dedicating roughly $12.7 billion to address the issue. And a separate package of infrastructure investment recently approved by the House would provide $40 billion instead. But both fall short of the $110 billion needed over the next 10 years to adequately address this crisis.

As congressional leaders work toward a common package, they must approve funding at levels that meet the need rather than focusing on the price tag.

The ordeal Linda McNeil has endured for the past two decades is a reminder of why this mission is so urgent, and why advancing environmental justice is a core part of what we have a right to expect from our government.

“Imagine what it’s like to pump your own waste out,” her daughter, Eileen, said. “And then write a check for your taxes.”

That shouldn’t be happening in Mount Vernon. It shouldn’t be happening anywhere.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

By Eleni Schirmer, August 27, 2021

Ms. Schirmer is a writer, teacher and organizer. She is currently a research associate with The Future of Finance Initiative at U.C.L.A.’s Luskin Institute on Inequality and Democracy.

For Philadelphia teacher Freda Anderson, setting up her classroom involves clearing plaster, dust and paint chips from tables, chairs and desks. Somewhere, a leak has allowed water to seep through the walls. Years of deferred maintenance have caused dust and paint chips to scatter across the room. This debris is not just a brazen reminder of state abandonment of public education — it is an active vector of harm. A report released this spring revealed an asbestos epidemic creeping through Philadelphia schools.

During the 2019 school year, 11 schools closed because of toxic physical conditions; a veteran teacher is suffering from mesothelioma, a lethal disease caused by asbestos. Ms. Anderson used to believe the best way to fix schools would be to hire more teachers, counselors, and mental health providers, “but, honestly, now the first thing I would do is start reallocating money to fix the buildings,” she told me. “They’re just really dangerous.”

The question of how to finance Philadelphia schools’ $4.5 billion of unmet infrastructure needs — as well as hiring more teachers, counselors and nurses — has been a vexing issue for the community. Despite high levels of affluence in the city, inequitable distribution of state aid and regressive taxation, including hundreds of millions of dollars in local corporate tax breaks, have exacerbated budget shortfalls.