Today, Friday, August 13, 2021, 7:00 P.M.

Wells Fargo Global Headquarters

420 Montgomery St.

San Francisco, CA 94104

Host Contact Info: info@OilGasAction.org

https://actionnetwork.org/events/defundline-3-sf-bay-area/

As part of the #DefundLine3 Global Day of Action - join us in downtown San Francisco for Guerrilla Movies and Community Art Action on Friday, August 13th from 7pm - 10pm

Bring chairs, blankets, and people power as we host a guerrilla movie screening and mass action at Wells Fargo's headquarters to help stop the Line 3 pipeline.

7:00pm — Non-Violent Direct Action training (at 555 California, 1/2 block from Wells Fargo)

8:30pm — Movie screening on the Line 3 resistance movement

Post-movie — Creative action (details will be shared on the ground)

Given the ongoing public health risks of COVID - while this event is outdoors, we still encourage attendees to be mindful of social distancing and wearing of masks.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

spiritofmandela.org

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

RALLY TO #SEALTHEDEAL FOR CLIMATE, JOBS, CARE AND JUSTICE: SAN FRANCISCO, CA

JOIN US ON THIS NATIONAL DAY OF ACTION AS THOUSANDS OF PEOPLE CALL ON OUR MEMBER OF CONGRESS TO SEAL THE DEAL AND PASS THE BIGGEST AND BOLDEST CLIMATE AND CARE INFRASTRUCTURE BILL IN HISTORY. WE CAN FUND CLIMATE SOLUTIONS, GROW THE CARE ECONOMY, FIGHT INEQUALITY, AND CREATE GREEN JOBS.

San Francisco Federal Building

90 7th St #2800

San Francisco, CA 94103

HOST: Megan Nguyen

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Let Cuba Live Exhibition

On the anniversary of the 26th of July Movement’s founding, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research launches the online exhibition, Let Cuba Live. 80 artists from 19 countries – including notable cartoonists and designers from Cuba – submitted over 100 works in defense of the Cuban Revolution. Together, the exhibition is a visual call for the end to the decades-long US-imposed blockade, whose effects have only deepened during the pandemic. The intentional blocking of remittances and Cuba’s use of global financial institutions have prevented essential food and medicine from entering the country. Together, the images in this exhibition demand: #UnblockCuba #LetCubaLive

Please contact art@thetricontinental.org if you are interested in organising a local exhibition of the exhibition.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Sincere Greetings of Peace:

The “In the Spirit of Mandela Coalition*” invites your participation and endorsement of the planned October 2021 International Tribunal. The Tribunal will be charging the United States government, its states, and specific agencies with human and civil rights violations against Black, Brown, and Indigenous people.

The Tribunal will be charging human and civil rights violations for:

• Racist police killings of Black, Brown, and Indigenous people,

• Hyper incarcerations of Black, Brown, and Indigenous people

• Political incarceration of Civil Rights/National Liberation era revolutionaries and activists, as well as present day activists,

• Environmental racism and its impact on Black, Brown, and Indigenous people,

• Public Health racism and disparities and its impact on Black, Brown, and Indigenous people, and

• Genocide of Black, Brown, and Indigenous people as a result of the historic and systemic charges of all the above.

The legal aspects of the Tribunal will be led by Attorney Nkechi Taifa along with a powerful team of seasoned attorneys from all the above fields. Thirteen jurists, some with international stature, will preside over the 3 days of testimonies. Testimonies will be elicited form impacted victims, expert witnesses, and attorneys with firsthand knowledge of specific incidences raised in the charges/indictment.

The 2021 International Tribunal has a unique set of outcomes and an opportunity to organize on a mass level across many social justice arenas. Upon the verdict, the results of the Tribunal will:

• Codify and publish the content and results of the Tribunal to be offered in High Schools and University curriculums,

• Provide organized, accurate information for reparation initiatives and community and human rights work,

• Strengthen the demand to free all Political Prisoners and establish a Truth and Reconciliation Commission mechanism to lead to their freedom,

• Provide the foundation for civil action in federal and state courts across the United States,

• Present a stronger case, building upon previous and respected human rights initiatives, on the international stage,

• Establish a healthy and viable massive national network of community organizations, activists, clergy, academics, and lawyers concerned with challenging human rights abuses on all levels and enhancing the quality of life for all people, and

• Establish the foundation to build a “Peoples’ Senate” representative of all 50 states, Indigenous Tribes, and major religions.

Endorsements are $25. Your endorsement will add to the volume of support and input vital to ensuring the success of these outcomes moving forward, and to the Tribunal itself. It will be transparently used to immediately move forward with the Tribunal outcomes.

We encourage you to add your name and organization to attend the monthly Tribunal updates and to sign on to one of the Tribunal Committees. (3rd Saturday of each month from 12 noon to 2 PM eastern time). Submit your name by emailing: spiritofmandela1@gmail.com

Please endorse now: http://spiritofmandela.org/endorse/

In solidarity,

Dr. A’isha Mohammad

Sekou Odinga

Matt Meyer

Jihad Abdulmumit

– Coordinating Committee

Created in 2018, In the Spirit of Mandela Coalition is a growing grouping of organizers, academics, clergy, attorneys, and organizations committed to working together against the systemic, historic, and ongoing human rights violations and abuses committed by the USA against Black, Brown, and Indigenous People. The Coalition recognizes and affirms the rich history of diverse and militant freedom fighters Nelson Mandela, Winnie Mandela, Graca Machel Mandela, Rosa Parks, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ella Baker, and many more. It is in their Spirit and affirming their legacy that we work.

https://spiritofmandela.org/campaigns/

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

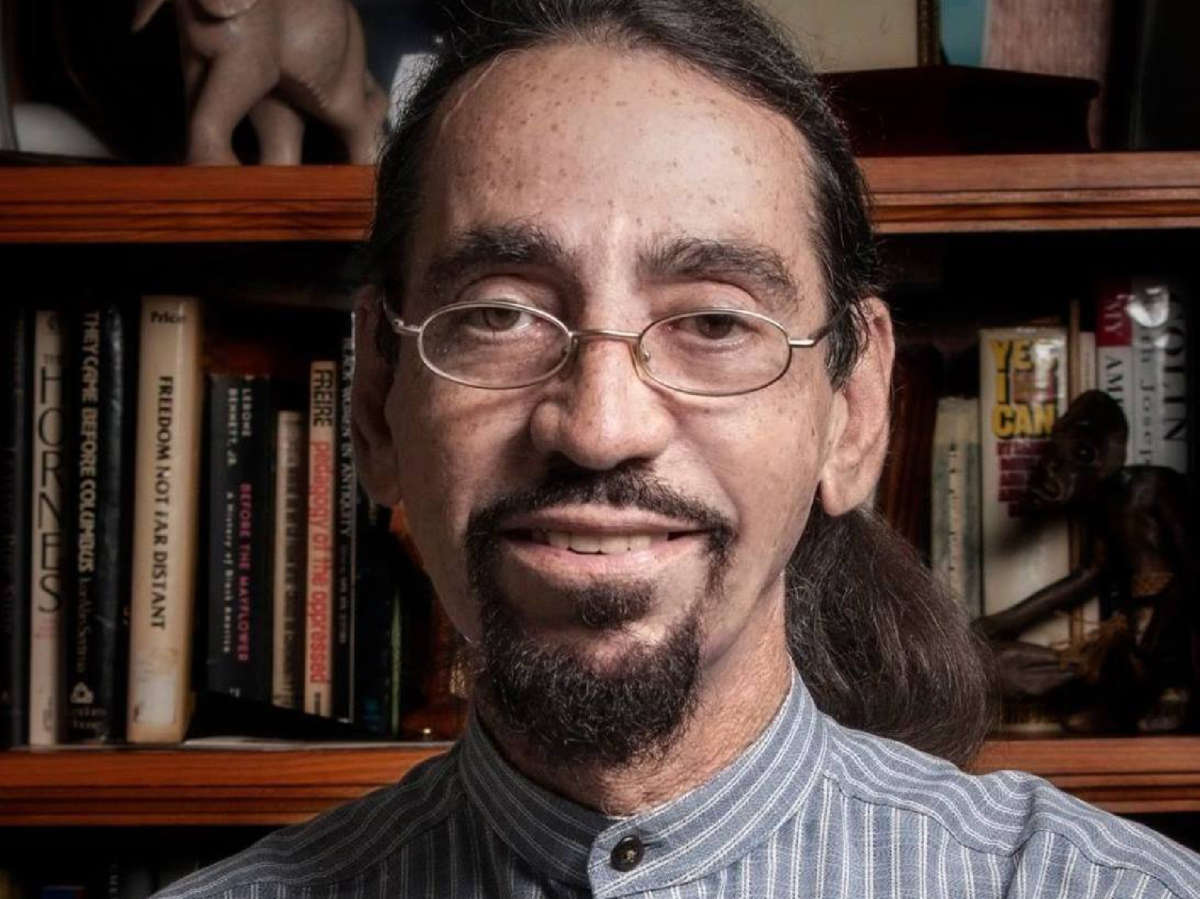

A BRILLIANT, BRAVE, BLACK POLITICAL JOURNALIST

|

|

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

PLEASE CALL AND EMAIL ON BEHALF OF KEVIN RASHID JOHNSON!

𝘼𝙡𝙡 𝙋2𝙋 𝙤𝙣 𝙩𝙝𝙞𝙨 𝙨𝙚𝙘𝙤𝙣𝙙 𝙙𝙖𝙮 𝙤𝙛 𝘽𝙡𝙖𝙘𝙠 𝘼𝙪𝙜𝙪𝙨𝙩. 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙘𝙤𝙢𝙧𝙖𝙙𝙚 𝙍𝙖𝙨𝙝𝙞𝙙 𝙨𝙩𝙞𝙡𝙡 𝙣𝙚𝙚𝙙𝙨 𝙤𝙪𝙧 𝙖𝙨𝙨𝙞𝙨𝙩𝙖𝙣𝙘𝙚. 𝙄𝙩 𝙞𝙨𝙞𝙢𝙥𝙚𝙧𝙖𝙩𝙞𝙫𝙚 𝙩𝙝𝙖𝙩 𝙘𝙖𝙡𝙡𝙨 𝙖𝙣𝙙 𝙚𝙢𝙖𝙞𝙡𝙨 𝙨𝙩𝙞𝙡𝙡 𝙗𝙚 𝙢𝙖𝙙𝙚 𝙤𝙣 𝙝𝙞𝙨 𝙗𝙚𝙝𝙖𝙡𝙛 𝙩𝙤 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙘𝙤𝙣𝙩𝙖𝙘𝙩𝙨 𝙡𝙞𝙨𝙩𝙚𝙙 𝙗𝙚𝙡𝙤𝙬. 𝙎𝙤𝙢𝙚𝙤𝙣𝙚𝙘𝙤𝙣𝙩𝙖𝙘𝙩𝙚𝙙 𝙢𝙚 𝙚𝙖𝙧𝙡𝙞𝙚𝙧 𝙩𝙤 𝙩𝙚𝙡𝙡 𝙢𝙚 𝙩𝙝𝙖𝙩 𝙍𝙖𝙨𝙝𝙞𝙙'𝙨 𝙘𝙚𝙡𝙡 𝙝𝙖𝙨 𝙗𝙚𝙚𝙣 𝙨𝙚𝙖𝙧𝙘𝙝𝙚𝙙 𝙩𝙬𝙞𝙘𝙚 𝙩𝙝𝙞𝙨 𝙢𝙤𝙧𝙣𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙖𝙨 𝙩𝙝𝙚𝙮𝙗𝙚𝙡𝙞𝙚𝙫𝙚 𝙩𝙝𝙖𝙩 𝙝𝙚 𝙞𝙨 𝙨𝙩𝙞𝙡𝙡 𝙘𝙤𝙢𝙢𝙪𝙣𝙞𝙘𝙖𝙩𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙬𝙞𝙩𝙝 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙤𝙪𝙩𝙨𝙞𝙙𝙚. 𝙏𝙝𝙚 𝙤𝙩𝙝𝙚𝙧 𝙥𝙧𝙞𝙨𝙤𝙣𝙚𝙧𝙨 𝙝𝙖𝙫𝙚 𝙗𝙚𝙚𝙣 𝙞𝙣𝙨𝙩𝙧𝙪𝙘𝙩𝙚𝙙𝙣𝙤𝙩 𝙩𝙤 𝙩𝙖𝙡𝙠 𝙩𝙤 𝙝𝙞𝙢 𝙤𝙧 𝙖𝙨𝙨𝙞𝙨𝙩 𝙝𝙞𝙢 𝙞𝙣 𝙖𝙣𝙮 𝙬𝙖𝙮. 𝙏𝙝𝙚 𝙥𝙞𝙜𝙨 𝙖𝙧𝙚 𝙖𝙩𝙩𝙚𝙢𝙥𝙩𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙩𝙤 𝙨𝙤𝙬 𝙙𝙞𝙫𝙞𝙨𝙞𝙤𝙣 𝙥𝙚𝙧 𝙪𝙨𝙪𝙖𝙡. - Shupavu Wa Kirima

𝙒𝙚 𝙖𝙧𝙚 𝙨𝙩𝙞𝙡𝙡 𝙙𝙚𝙢𝙖𝙣𝙙𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙛𝙤𝙡𝙡𝙤𝙬𝙞𝙣𝙜:

1. 𝘼𝙣 𝙚𝙣𝙙 𝙩𝙤 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙗𝙤𝙜𝙪𝙨 30 𝙙𝙖𝙮 𝙧𝙚𝙨𝙩𝙧𝙞𝙘𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣 𝙛𝙧𝙤𝙢 𝙥𝙝𝙤𝙣𝙚 𝙖𝙣𝙙 𝙚𝙢𝙖𝙞𝙡.

2. 𝘼𝙣 𝙚𝙣𝙙 𝙩𝙤 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙗𝙤𝙜𝙪𝙨 30 𝙙𝙖𝙮 𝙧𝙚𝙨𝙩𝙧𝙞𝙘𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣 𝙛𝙧𝙤𝙢 𝙘𝙤𝙢𝙢𝙞𝙨𝙨𝙖𝙧𝙮 𝙩𝙝𝙖𝙩 𝙥𝙧𝙚𝙫𝙚𝙣𝙩𝙨 𝙍𝙖𝙨𝙝𝙞𝙙 𝙛𝙧𝙤𝙢 𝙤𝙧𝙙𝙚𝙧𝙞𝙣𝙜𝙨𝙩𝙖𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣𝙚𝙧𝙮 𝙬𝙞𝙩𝙝 𝙬𝙝𝙞𝙘𝙝 𝙩𝙤 𝙬𝙧𝙞𝙩𝙚.

3. 𝙏𝙝𝙚 𝙞𝙢𝙢𝙚𝙙𝙞𝙖𝙩𝙚 𝙧𝙚𝙩𝙪𝙧𝙣 𝙤𝙛 𝘼𝙇𝙇 𝙤𝙛 𝙝𝙞𝙨 𝙥𝙧𝙤𝙥𝙚𝙧𝙩𝙮 𝙞𝙣𝙘𝙡𝙪𝙙𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙩𝙝𝙚 $400 𝙩𝙝𝙖𝙩 𝙬𝙖𝙨 𝙤𝙣 𝙝𝙞𝙨 𝙩𝙧𝙪𝙨𝙩 𝙖𝙘𝙘𝙤𝙪𝙣𝙩𝙩𝙝𝙚𝙧𝙚 𝙖𝙩 𝙒𝙑𝘾𝙁 𝙖𝙣𝙙 𝙝𝙞𝙨 𝙡𝙚𝙜𝙖𝙡 𝙥𝙧𝙤𝙥𝙚𝙧𝙩𝙮 𝙬𝙝𝙞𝙘𝙝 𝙬𝙞𝙡𝙡 𝙚𝙣𝙖𝙗𝙡𝙚 𝙝𝙞𝙢 𝙩𝙤 𝙘𝙤𝙣𝙩𝙞𝙣𝙪𝙚 𝙬𝙞𝙩𝙝 𝙝𝙞𝙨 𝙘𝙖𝙨𝙚 𝙖𝙜𝙖𝙞𝙣𝙨𝙩 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙄𝙉𝘿𝙚𝙥𝙖𝙧𝙩𝙢𝙚𝙣𝙩 𝙤𝙛 𝘾𝙤𝙧𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣𝙨. 𝙄𝙛 𝙩𝙝𝙚𝙮 𝙩𝙚𝙡𝙡 𝙮𝙤𝙪 𝙩𝙝𝙖𝙩 𝙝𝙞𝙨 𝙥𝙧𝙤𝙥𝙚𝙧𝙩𝙮 𝙝𝙖𝙨 𝙖𝙡𝙧𝙚𝙖𝙙𝙮 𝙗𝙚𝙚𝙣 𝙨𝙚𝙣𝙩 𝙩𝙝𝙚𝙣 𝙬𝙚 𝙣𝙚𝙚𝙙 𝙩𝙤𝙠𝙣𝙤𝙬 𝙤𝙣 𝙬𝙝𝙖𝙩 𝙙𝙖𝙩𝙚 𝙞𝙩 𝙬𝙖𝙨 𝙨𝙝𝙞𝙥𝙥𝙚𝙙 𝙖𝙣𝙙 𝙬𝙝𝙖𝙩 𝙛𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙡𝙞𝙩𝙮 𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙚𝙞𝙫𝙚𝙙 𝙞𝙩.

𝙏𝙝𝙖𝙣𝙠 𝙮𝙤𝙪 𝙖𝙡𝙡 𝙨𝙤 𝙢𝙪𝙘𝙝 𝙛𝙤𝙧 𝙮𝙤𝙪𝙧 𝙨𝙤𝙡𝙞𝙙𝙖𝙧𝙞𝙩𝙮 𝙖𝙣𝙙 𝙨𝙪𝙥𝙥𝙤𝙧𝙩. 𝙄 𝙖𝙥𝙥𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙞𝙖𝙩𝙚 𝙖𝙡𝙡 𝙤𝙛 𝙮𝙤𝙪. 𝙒𝙚 𝙖𝙧𝙚 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙊𝙉𝙇𝙔𝙡𝙞𝙣𝙚 𝙤𝙛 𝙙𝙚𝙛𝙚𝙣𝙨𝙚 𝙛𝙤𝙧 𝙤𝙪𝙧 𝙞𝙢𝙥𝙧𝙞𝙨𝙤𝙣𝙚𝙙 𝙘𝙤𝙢𝙧𝙖𝙙𝙚𝙨.

* 𝘼𝙣𝙣𝙚𝙩𝙩𝙚 𝘾𝙝𝙖𝙢𝙗𝙚𝙧𝙨-𝙎𝙢𝙞𝙩𝙝, 𝘿𝙞𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙩𝙤𝙧 𝙤𝙛 𝙊𝙝𝙞𝙤 𝘿𝙚𝙥𝙖𝙧𝙩 𝙤𝙛 𝙍𝙚𝙝𝙖𝙗𝙞𝙡𝙞𝙩𝙖𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣 𝙖𝙣𝙙 𝘾𝙤𝙧𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣𝙨 𝙥𝙡𝙚𝙖𝙨𝙚𝙘𝙤𝙣𝙩𝙖𝙘𝙩: 𝙈𝙚𝙡𝙞𝙨𝙨𝙖 𝘼𝙙𝙠𝙞𝙣𝙨 (𝙀𝙭𝙚𝙘𝙪𝙩𝙞𝙫𝙚 𝘼𝙨𝙨𝙞𝙨𝙩𝙖𝙣𝙩) 𝙫𝙞𝙖 𝙚𝙢𝙖𝙞𝙡: 𝙢𝙚𝙡𝙞𝙨𝙨𝙖.𝙖𝙙𝙠𝙞𝙣𝙨@𝙤𝙙𝙧𝙘.𝙨𝙩𝙖𝙩𝙚.𝙤𝙝.𝙪𝙨 𝙤 614-752-1153.

* 𝙍𝙤𝙣𝙖𝙡𝙙 𝙀𝙧𝙙𝙤𝙨, 𝙎𝙤𝙪𝙩𝙝𝙚𝙧𝙣 𝙊𝙝𝙞𝙤 𝘾𝙤𝙧𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣𝙖𝙡 𝙁𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙡𝙞𝙩𝙮, 𝙒𝙖𝙧𝙙𝙚𝙣 (𝙇𝙪𝙘𝙖𝙨𝙫𝙞𝙡𝙡𝙚) (740)259-5544 𝙙𝙧𝙘.𝙨𝙤𝙘𝙛@𝙤𝙙𝙧𝙘.𝙨𝙩𝙖𝙩𝙚.𝙤𝙝𝙞𝙤.𝙪𝙨

*𝙅𝙤𝙨𝙚𝙥𝙝 𝙒𝙖𝙡𝙩𝙚𝙧𝙨, 𝘿𝙚𝙥. 𝘿𝙞𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙩𝙤𝙧 𝙑𝙞𝙧𝙜𝙞𝙣𝙞𝙖 𝘿𝙚𝙥𝙖𝙧𝙩𝙢𝙚𝙣𝙩 𝙊𝙛 𝘾𝙤𝙧𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣𝙨𝙟𝙤𝙨𝙚𝙥𝙝.𝙬𝙖𝙡𝙩𝙚𝙧𝙨@𝙫𝙖𝙙𝙤𝙘.𝙫𝙞𝙧𝙜𝙞𝙣𝙞𝙖.𝙜𝙤𝙫 (𝙋𝙧𝙤𝙭𝙮 𝙛𝙤𝙧 𝙃𝙖𝙧𝙤𝙡𝙙 𝙒. 𝘾𝙡𝙖𝙧𝙠𝙚, 𝘿𝙞𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙩𝙤𝙧 𝙤𝙛 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝘿𝙚𝙥𝙖𝙧𝙩𝙢𝙚𝙣𝙩 𝙤𝙛𝘾𝙤𝙧𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣𝙨) (804)887-7982

*𝙅𝙖𝙢𝙚𝙨 𝙋𝙖𝙧𝙠, 𝙄𝙣𝙩𝙚𝙧𝙨𝙩𝙖𝙩𝙚 𝘾𝙤𝙢𝙥𝙖𝙘𝙩 𝘼𝙙𝙢𝙞𝙣𝙞𝙨𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙩𝙤𝙧 𝙅𝙖𝙢𝙚𝙨.𝙥𝙖𝙧𝙠@𝙫𝙖𝙙𝙤𝙘.𝙫𝙞𝙧𝙜𝙞𝙣𝙞𝙖.𝙜𝙤𝙫

* 𝘾𝙝𝙖𝙧𝙡𝙚𝙣𝙚 𝘽𝙪𝙧𝙠𝙚𝙩𝙩, 𝘿𝙞𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙩𝙤𝙧 𝘿𝙊𝘾 𝙊𝙢𝙗𝙪𝙙𝙨𝙢𝙖𝙣 𝘽𝙪𝙧𝙚𝙖𝙪 (𝙄𝙣𝙙𝙞𝙖𝙣𝙖) (317) 234-3190 𝙊𝙢𝙗𝙪𝙙@𝙞𝙙𝙤𝙖.𝙞𝙣.𝙜𝙤𝙫 𝙍𝙞𝙘𝙝𝙖𝙧𝙙 𝘽𝙧𝙤𝙬𝙣, 𝙒𝙖𝙧𝙙𝙚𝙣 𝙒𝙖𝙗𝙖𝙨𝙝 𝙑𝙖𝙡𝙡𝙚𝙮 𝘾𝙤𝙧𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣𝙖𝙡 𝙁𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙡𝙞𝙩𝙮, 𝙄𝙣𝙙𝙞𝙖𝙣𝙖 (812) 398-5050

* 𝙍𝙞𝙘𝙝𝙖𝙧𝙙 𝘽𝙧𝙤𝙬𝙣, 𝙒𝙖𝙧𝙙𝙚𝙣 𝙒𝙖𝙗𝙖𝙨𝙝 𝙑𝙖𝙡𝙡𝙚𝙮 𝘾𝙤𝙧𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣𝙖𝙡 𝙁𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙡𝙞𝙩𝙮, 𝙄𝙣𝙙𝙞𝙖𝙣𝙖 (812) 398-5050

*𝙘𝙤𝙣𝙩𝙖𝙘𝙩 𝙑𝙞𝙧𝙜𝙞𝙣𝙖 𝘿𝙊𝘾 𝙖𝙪𝙩𝙝𝙤𝙧𝙞𝙩𝙞𝙚𝙨 𝙗𝙚𝙘𝙖𝙪𝙨𝙚 𝙑𝘼 𝙥𝙧𝙞𝙨𝙤𝙣𝙚𝙧𝙨 𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙣𝙨𝙛𝙚𝙧𝙧𝙚𝙙 𝙤𝙣 𝙞𝙣𝙩𝙚𝙧-𝙨𝙩𝙖𝙩𝙚 𝙘𝙤𝙢𝙥𝙖𝙘𝙩𝙨 𝙖𝙧𝙚𝙨𝙪𝙥𝙥𝙤𝙨𝙚𝙙 𝙩𝙤 𝙝𝙖𝙫𝙚 𝙖𝙡𝙡 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙧𝙞𝙜𝙝𝙩𝙨 𝙤𝙛 𝙑𝘼 𝙥𝙧𝙞𝙨𝙤𝙣𝙚𝙧𝙨. 𝙍𝙖𝙨𝙝𝙞𝙙 𝙬𝙖𝙨 𝙤𝙧𝙞𝙜𝙞𝙣𝙖𝙡𝙡𝙮 𝙞𝙣𝙘𝙖𝙧𝙘𝙚𝙧𝙖𝙩𝙚𝙙 𝙞𝙣 𝙑𝘼 𝙗𝙚𝙛𝙤𝙧𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙣𝙨𝙛𝙚𝙧𝙨 𝙩𝙤 𝙊𝙧𝙚𝙜𝙤𝙣, 𝙏𝙚𝙭𝙖𝙨, 𝙁𝙡𝙤𝙧𝙞𝙙𝙖, 𝙄𝙣𝙙𝙞𝙖𝙣𝙖, 𝙖𝙣𝙙 𝙣𝙤𝙬 𝙊𝙝𝙞𝙤.

Our mailing address is:

Kevin Rashid Johnson

D.O.C. #A787991

P.O. Box 45699

Lucasville, OH 45699

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

THE RIBPP & PSO'S STATEMENT ON COMRADE KEVIN RASHID JOHNSON

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

08/06/2021

All Power to the People!

Kevin “Rashid” Johnson is a political theorist, artist, and advocate for prisoners’ rights who has spent almost his entire adult life incarcerated in various U.S. prisons. A founder of the Revolutionary Intercommunal Black Panther Party (and, before that, of the New Afrikan Black Panther Party-Prison Chapter), Rashid’s writings and litigation have made him the target of continual and ongoing repression from prison authorities.

Rashid, as he is known to friends and supporters, was recently transferred to Ohio from the Indiana Department of Corrections (IDOC). This is just the latest in a series of transfers between multiple correctional facilities and state jurisdictions, all made possible by the Interstate Compact Transfer Agreement. As such, although originally a prisoner of the Virginia Department of Corrections (VADOC), Rashid has been sent to Oregon, Texas, Florida, and Indiana, prior to his current captivity in Ohio.

This most recent transfer was initiated in an attempt to obstruct litigation Rashid is currently pressing against IDOC for its use of solitary confinement and treatment of prisoners while in solitary confinement. Rashid was told by IDOC officials a week prior to his transfer that if he persisted and did not drop the cases he would be transferred to someplace where he "would not like the conditions." This retaliatory transfer has made it impossible for Rashid to access legal property and materials needed to meet court deadlines, answer motions, and respond to the court. Prior to this transfer, Rashid warned IDOC that he would be seeking citations of contempt in regard to IDOC's attempt at entering false evidence and concealing other evidentiary material in one of Rashid's pending cases. (IDOC has been sanctioned previously for submitting false evidence and concealing evidence in Indiana's Southern District U.S. Federal Court and settled for over $100,000; see Littler v. Martinez.)

Rashid is being denied access to the phone, legal property, and to commissary where he would be able to purchase stationery to continue his litigation against the IDOC. It is clear and apparent at this point that the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Corrections (ODRC) is colluding with IDOC in their attempt to deny Rashid his right to pursue these cases.

Rashid is currently being held at the notorious Southern Ohio Correctional Facility (SOCF) in Lucasville, where, in April of 1993, nine prisoners were killed in an eleven-day standoff with prison staff. The legacy of racist, fascist brutality continues to thrive at SOCF. Mr. Johnson has been moved to the area of the prison where various white supremacist gangs are most concentrated.

It was there on Monday, August 2, 2021, that according to Rashid, Sgt. Joshua McAllister threatened him with the following statements:

“I’m an old school dirty cop. I’ve been doing this since I was a teenager. We know how to set it up and make it look justified. You must not know about us. We are worse than the Klan… We have a unit where we execute inmates. We starve ‘em. We hang ‘em.”

That a prison official would be so bold in 2021, just one year after the Rebellion of Summer 2020, as to issue such threats to a Black prisoner, given the current climate around race relations and law enforcement, will not be tolerated. This needs to be understood. This is an example of the depravity and cruelty of the U.S. prison system and of many of those who work within it. Prisons frequently move incarcerated people out of public view, torturing, disappearing, and killing them without any visibility or accountability for their actions.

Rashid is a long-time political leader, writer, artist, activist and organizer. He is being targeted because of his political beliefs, his many published pieces documenting prison abuse and torture, and efforts at organizing for better conditions. Rashid, completely self-taught in the fields of law and political theory/practice, has become well known both nationally and internationally, as someone who is always willing to put himself on the line on behalf of his fellow incarcerated comrades, and marginalized and oppressed people

everywhere. It is for this reason that the ODRC, IDOC, and VADOC, in conjunction with other state/federal agencies, continue to try and silence Rashid through intimidation, torture, beatings, threats, and outright attempted murder.

WE WILL NOT STAND FOR IT! AND WE PETITION EVERYONE WHO SEES THIS STATEMENT TO JOIN WITH US IN SOLIDARITY AND DEFENSE OF THIS COURAGEOUS FREEDOM FIGHTER!

WE, THE UNDERSIGNED*,

DEMAND THE FOLLOWING:

· AN END TO THE 30 DAY RESTRICTION FROM COMMUNICATING VIA PHONE/EMAIL.

· AN END TO THE 30 DAY RESTRICTION FROM COMMISSARY THAT PREVENTS RASHID FROM ORDERING STATIONERY WITH WHICH TO WRITE.

· THE IMMEDIATE RETURN OF ALL OF HIS PROPERTY, INCLUDING THE $400 THAT WAS ON HIS TRUST ACCOUNT AT WABASH VALLEY CORRECTIONAL FACILITY AND HIS LEGAL PROPERTY, WHICH WILL ENABLE HIM TO CONTINUE WITH HIS CASES AGAINST THE INDIANA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS. IF HIS PROPERTY HAS ALREADY BEEN SENT, WE WANT TO KNOW ON WHAT DATE IT WAS SHIPPED AND WHAT FACILITY RECEIVED IT.

· WE DEMAND THAT SGT. JOSHUA MCALLISTER FACE IMMEDIATE CONSEQUENCES FOR THE DISGUSTINGLY RACIST THREATS INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO HIS REMOVAL FROM HIS POST AT SOCF!

· LASTLY, WE DEMAND AN IMMEDIATE INVESTIGATION/INQUIRY INTO THE SUPPOSED J-1 UNIT AND ALL PARTIES INVOLVED.

DARE TO STRUGGLE, DARE TO WIN!

ALL POWER TO THE PEOPLE!

For further inquiries on how to assist in this cause, please contact comrade Shupavu Wa Kirima at:

general.secretary@ribpp.org

Notes & citations:

Littler v. Martinez

a. https://casetext.com/case/littler-v-martinez-2

b. https://rashidmod.com/?p=2887

*Organizations who are endorsing this statement: Revolutionary Intercommunal Black Panther Party (RIBPP), Panther Solidarity Organization (PSO)-Newark, PSO-Ridgewood, PSO-Boston, PSO-Richmond, PSO-Kansas City, Third World Peoples' Alliance (TWPA), Kersplebedeb Publishing, Newark Water Coalition, Ridgewood For Black Liberation, Tennessee Valley Mutual Aid, For The People (FTP)-STL, FTP-Chicago, FTP-Bloomington, FTP-Cleveland, FTP-Wichita, FTP-OK, Oklahoma People's Party, Autonomous Brown Berets of Oklahoma, Young EcoSocialists-New Jersey, Party For Communism and Revolution, Serve The People (STP)-Akron, IDOC Watch, Roanoke Jail Solidarity, Princeton Mutual Aid, San Francisco Bay View

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Freedom for Major Tillery! End his Life Imprisonment!

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

On July 27th whistleblower Daniel Hale was sentenced to 45 months in federal prison for exposing the US drone program. CODEPINK has known Daniel since he spoke at our Drone Summit in 2013. There are a few ways you can support Daniel at this time, and one way to do that is write him letters! Daniel loves receiving letters. Please return to this page in the future, as his address will change once he moves facilities to carry out his sentence.

Send to:

Daniel E. Hale

William G. Truesdale Adult Detention Ctr.

2001 Mill Rd.

Alexandria, VA 22314

Please also visit standwithdanielhale.org, which is run by Daniel's core support team to see updates and other ways to support him.

Sign the petition at:

https://www.codepink.org/danielhale?utm_campaign=daniel_hale_national&utm_medium=email&utm_source=codepinkDANIEL HALE SENTENCED TO 45 MONTHS IN PRISON FOR DRONE LEAK

“I am here because I stole something that was never mine to take — precious human life,” Hale said at his sentencing.

https://theintercept.com/2021/07/27/daniel-hale-drone-leak-sentencing/

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Hi everyone,

We hope all is well with you.

We are happy to announce that the video recording of "No Life Like It: A A Tribute to the Revolutionary Activism of Ernie Tate" is now available for viewing on LeftStreamed

here: https://youtu.be/_sXWHaIC8D0

and here: https://socialistproject.ca/leftstreamed-video/no-life-like-it/

Please share the link with your comrades and friends.

All the best,

The organizers

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Photo from San Francisco rally and march in support of Palestine Saturday, May 15, 2021

Stand with Palestine!

Say NO to apartheid!

Join the global movement in solidarity with the Palestinian people.

#DefendJerusalem

#SaveSheikhJarrah

#Nakba73 #homeisworthstrugglingfor

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Contact Us

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

Contact: Governor's Press Office

Friday, May 28, 2021

(916) 445-4571

Governor Newsom Announces Clemency Actions, Signs Executive Order for Independent Investigation of Kevin Cooper Case

SACRAMENTO – Governor Gavin Newsom today announced that he has granted 14 pardons, 13 commutations and 8 medical reprieves. In addition, the Governor signed an executive order to launch an independent investigation of death row inmate Kevin Cooper’s case as part of the evaluation of Cooper’s application for clemency.

The investigation will review trial and appellate records in the case, the facts underlying the conviction and all available evidence, including the results of the recently conducted DNA tests previously ordered by the Governor to examine additional evidence in the case using the latest, most scientifically reliable forensic testing.

The text of the Governor’s executive order can be found here:

https://www.gov.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/5.28.21-EO-N-06-21.pdf

The California Constitution gives the Governor the authority to grant executive clemency in the form of a pardon, commutation or reprieve. These clemency grants recognize the applicants’ subsequent efforts in self-development or the existence of a medical exigency. They do not forgive or minimize the harm caused.

The Governor regards clemency as an important part of the criminal justice system that can incentivize accountability and rehabilitation, increase public safety by removing counterproductive barriers to successful reentry, correct unjust results in the legal system and address the health needs of incarcerated people with high medical risks.

A pardon may remove counterproductive barriers to employment and public service, restore civic rights and responsibilities and prevent unjust collateral consequences of conviction, such as deportation and permanent family separation. A pardon does not expunge or erase a conviction.

A commutation modifies a sentence, making an incarcerated person eligible for an earlier release or allowing them to go before the Board of Parole Hearings for a hearing at which Parole Commissioners determine whether the individual is suitable for release.

A reprieve allows individuals classified by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation as high medical risk to serve their sentences in appropriate alternative placements in the community consistent with public health and public safety.

The Governor weighs numerous factors in his review of clemency applications, including an applicant’s self-development and conduct since the offense, whether the grant is consistent with public safety and in the interest of justice, and the impact of a grant on the community, including crime victims and survivors.

While in office, Governor Newsom has granted a total of 86 pardons, 92 commutations and 28 reprieves.

The Governor’s Office encourages victims, survivors, and witnesses to register with CDCR’s Office of Victims and Survivors Rights and Services to receive information about an incarcerated person’s status. For general Information about victim services, to learn about victim-offender dialogues, or to register or update a registration confidentially, please visit:

www.cdcr.ca.gov/Victim_Services/ or call 1-877-256-6877 (toll free).

Copies of the gubernatorial clemency certificates announced today can be found here:

https://www.gov.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/5.28.21-Clemency-certs.pdf

Additional information on executive clemency can be found here:

https://www.gov.ca.gov/clemency/

###

I don’t usually do this. This is discussing my self. I find it far more interesting to tell the stories of other, the revolving globe on which we dwell and the stories spawn by the fragile human condition and the struggles of humanity for liberation.

But I digress, uncomfortably.

This commentary is about the commentator.

Several weeks ago I underwent a medical procedure known as open heart surgery, a double bypass after it was learned that two vessels beating through my heart has significant blockages that impaired heart function.

This impairment was fixed by extremely well trained and young cardiologist who had extensive experience in this intricate surgical procedure.

I tell you I had no clue whatsoever that I suffered from such disease. Now to be perfectly honest, I feel fine.

Indeed, I feel more energetic than usual!

I thank you all, my family and friends, for your love and support.

Onwards to freedom with all my heart.

—Mumia Abu-Jamal

Questions and comments may be sent to: info@freedomarchives.org

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Jeff Bezos has at least $180 Billion!

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

9 minutes 29 seconds

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Resources for Resisting Federal Repression

Since June of 2020, activists have been subjected to an increasingly aggressive crackdown on protests by federal law enforcement. The federal response to the movement for Black Lives has included federal criminal charges for activists, door knocks by federal law enforcement agents, and increased use of federal troops to violently police protests.

The NLG National Office is releasing this resource page for activists who are resisting federal repression. It includes a link to our emergency hotline numbers, as well as our library of Know-Your-Rights materials, our recent federal repression webinar, and a list of some of our recommended resources for activists. We will continue to update this page.

Please visit the NLG Mass Defense Program page for general protest-related legal support hotlines run by NLG chapters.

Emergency Hotlines

If you are contacted by federal law enforcement you should exercise all of your rights. It is always advisable to speak to an attorney before responding to federal authorities.

State and Local Hotlines

If you have been contacted by the FBI or other federal law enforcement, in one of the following areas, you may be able to get help or information from one of these local NLG hotlines for:

- Portland, Oregon: (833) 680-1312

- San Francisco, California: (415) 285-1041 or fbi_hotline@nlgsf.org

- Seattle, Washington: (206) 658-7963

National Hotline

If you are located in an area with no hotline, you can call the following number:

Know Your Rights Materials

The NLG maintains a library of basic Know-Your-Rights guides.

- Know Your Rights During Covid-19

- You Have The Right To Remain Silent: A Know Your Rights Guide for Encounters with Law Enforcement

- Operation Backfire: For Environmental and Animal Rights Activists

WEBINAR: Federal Repression of Activists & Their Lawyers: Legal & Ethical Strategies to Defend Our Movements: presented by NLG-NYC and NLG National Office

We also recommend the following resources:

Center for Constitutional Rights

Civil Liberties Defense Center

- Grand Juries: Slideshow

Grand Jury Resistance Project

Katya Komisaruk

Movement for Black Lives Legal Resources

Tilted Scales Collective

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Truthout, July 31, 2021

https://truthout.org/articles/glen-fords-journalism-fought-for-Black-liberation-and-against-imperialism/

I had the honor of working with the late Glen Ford for nearly 20 years. His passing has created a huge void not just for Black Agenda Report (BAR), the site we co-founded with the late Bruce Dixon, but for all of Black politics and left media. Ford identified his political and journalistic stance with both, having created the tagline: “News, commentary and analysis from the Black left” for BAR. He was the consummate journalist, a man who demanded rigorous analysis of himself and others, and he lived by the dictum of afflicting the comfortable and comforting the afflicted. Ford co-founded a publication in line with his core values: He did not suffer fools gladly, succumb to corporate media and government narratives, or feel obligated to change his politics in order to elevate the Black face in a high place.

Ford spoke of learning this lesson the hard way. He told a story of regret, his ethical dilemma, when he gave one such Black person, Barack Obama, a pass in 2003. At that time, Ford, Dixon and I were all working at Black Commentator. Obama had announced his candidacy for the United States Senate and he was listed as a member of the Democratic Leadership Council (DCL), the right-leaning, corporate wing of the Democratic Party. Obama had also removed an antiwar statement from his website.

Ford and Dixon posed what they called “bright line questions” to Obama on issues such as the North American Free Trade Agreement, single-payer healthcare and Iraq. His fuzzy answers should have flunked him, but Ford chose not to be seen as “a crab in a barrel,” one who pulled another of the group down. Obama was given an opportunity to comment in Black Commentator and Ford wrote, “[Black Commentator] is relieved, pleased, and looking forward to Obama’s success in the Democratic senatorial primary and Illinois general election.”

As he witnessed Obama’s actions on the campaign trail and eventually in office, Ford never again felt obligated to depart from his political stances or to defend a member of the group whose politics were not in keeping with the views of the Black left.

From that moment on, Glen Ford did not let up on Obama, just as he did not waver from his staunch opposition to neoliberalism and U.S. imperialism. Black Agenda Report became the go-to site for all leftists. BAR’s critique of Obama when he led the destruction of Libya was no less stinging than critiques of George W. Bush when the U.S. invaded Iraq. Ford declared that Obama and the Democrats were not the “lesser evil” that millions of people hoped for. Instead, they were just the more effective evil, and they were always in BAR’s journalistic sights.

Ford was always an uncompromising defender of Black people and never shrank from explaining the mechanisms which place that group at or near the bottom of all positive metrics and at or near the top of all the negative. He was one of the first to amplify the term “mass incarceration” in his unsparing analysis of the United States and its dubious distinction as the nation with more people behind bars than any other: more than two million, with half of those being Black, a cohort which makes up one-quarter of all the incarcerated in the world. Black Agenda Report can be counted on to give this information consistently and with no punches pulled.

Glen Ford was a committed socialist, a Vietnam-era military veteran and a member of the Black Panther Party. He spent part of his childhood and youth in Columbus, Georgia, in the days of apartheid in the United States. Those life experiences shaped his work and left a legacy that anyone who considers themselves a leftist ought to follow.

He worked in the media throughout his adult life and served as a Capitol Hill, White House and State Department correspondent for the Mutual Black Network. In 1977, he co-found “America’s Black Forum,” which was the first nationally syndicated, Black-oriented program on commercial television.

Now the number of media outlets is very small, thanks in large part to Bill Clinton’s 1996 Telecommunications Act. Just six corporations control 90 percent of all media we read, watch, and hear, and that means that there are very few working journalists, and an even smaller number with Ford’s experience and worldview. The most “successful” of those who fall into the category of journalists are mostly scribes, repeating the narratives which are favored by politicians and the corporate media.

We desperately need left media and journalists like Glen Ford. Any reader of Black Agenda Report won’t expect The New York Times or The Washington Post to tell them what is happening in Haiti or Cuba. Thanks to Ford’s consistent analysis, they understand that even those who want to be well informed seldom are unless they also read Black Agenda Report.

Glen Ford will be missed by all who knew him and by all BAR readers. He and journalists of his ilk are small in number and irreplaceable.

Glen Ford ¡presente!

—Truthout, July 31, 2021

https://truthout.org/articles/glen-fords-journalism-fought-for-Black-liberation-and-against-imperialism/

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Jacobin, August 5, 2021

https://jacobinmag.com/2021/08/daniel-hale-drone-whistleblower-sentencing-trial?mc_cid=8a8e61d10f&mc_eid=49b76e976c

Daniel Hale in the 2016 documentary National Bird. (Independent Lens / PBS)

On July 27, 2021, Judge Liam O’Grady sentenced drone whistleblower Daniel Hale to three years and nine months in federal prison. The courtroom was packed with supporters, including friends, whistleblowers who themselves had faced criminal prosecution, peace activists, and press freedom advocates. As U.S. marshals took Hale away, a housemate of his shouted out, “We’ll see you soon, Dan.” Soon, nearly everyone in the packed gallery of the courtroom was standing, waving goodbye to Hale. “Thank you,” was heard again and again, as people called out to the former soldier who had risked everything to expose the brutality of the United States’ global assassination program.

Three days later, while the Department of Justice and Office of the Director of National Intelligence were tweeting about National Whistleblower Appreciation Day, Hale was being transferred to the Northern Neck Regional Jail. He is currently being held in a room with one hundred people, deprived of a mattress, a blanket, a change of clothes, and visitors.

Under any circumstances, such conditions of confinement are abhorrent. No society that values the inherent dignity of human beings would subject anyone to them, regardless of what they were convicted of. That Hale’s “crime” is telling the truth about U.S. war crimes compounds the outrageousness of the situation. Even the federal judge who sent Hale to prison acknowledged that Hale had shown great courage in his attempts to alert the public to the drone war’s human toll.

The emergence of a whistleblower

Hale was convicted under the Espionage Act. His crime consisted of taking classified information about the U.S. drone program and giving it to journalist Jeremy Scahill. This information later formed the basis for a series of articles published by the Intercept called “The Drone Papers.”

Thanks to Hale’s disclosures, the public learned that, during one five-month period in Afghanistan, 90 percent of those killed by U.S. air strikes were not the intended targets. In addition to classified documents about the United States’ global assassination program, Hale also disclosed unclassified (but still not publicly available) guidelines for the U.S. terror watch list. As a direct result, individuals were able to successfully challenge their placement on the No-Fly List.

In the run-up to the sentencing, Hale wrote a handwritten letter to the judge explaining his actions. (I also submitted a letter to the judge, at the request of Hale’s lawyers.) Similarly, during the hearing itself, Hale, often on the verge of tears, delivered a seventeen-minute speech to the court. Both Hale’s letter and his speech were deeply moving portraits of how his conscience brought him to take action against the United States’ global assassination program.

As Hale explained, the first part of his life was particularly rough. In 2009, facing homelessness, he joined the U.S. military. He had opposed U.S. wars, but he believed that newly elected president Barack Obama was winding them down. Besides, he had few choices given his economic realities. The military discovered Hale had a knack for learning languages and taught him Mandarin.

In 2012, at age twenty-four, Hale was sent to Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan to work as a signal intelligence analyst. Bagram was a key part of the “kill chain,” and Hale’s role was to track the location of cell phones believed to belong to “enemy combatants.” This locating of phones allowed the U.S. government to track their possessor with drones, which were equipped with cameras and could be used to surveil their day-to-day life. Drones, however, are used to not only watch but also to kill.

Just days after his arrival, Hale witnessed for the first time what that looked like. A suspected member of the Taliban had gathered with others in the early morning to drink tea. His companions were armed, but, as Hale pointed out, carrying arms was uncommon neither for people where he grew up nor in the regions of Afghanistan outside of government control. However, because they were military-age, armed, and in the vicinity of the United States’ target, that subjected them to guilt by association sufficient for a summary death sentence.

As Hale explained:

“Despite having peacefully assembled, posing no threat, the fate of the now-tea-drinking men had all but been fulfilled. I could only look on as I sat by and watched through a computer monitor when a sudden, terrifying flurry of hellfire missiles came crashing down, splattering purple-colored crystal guts on the side of the morning mountain.”

That memory stuck with Hale. He says not a day went by without him questioning his justifications:

“By the rules of engagement, it may have been permissible for me to have helped to kill those men—whose language I did not speak, customs I did not understand, and crimes I could not identify—in the gruesome manner that I did. Watch them die. But how could it be considered honorable of me to continuously have laid in wait for the next opportunity to kill unsuspecting persons, who, more often than not, are posing no danger to me or any other person at the time?”

Another incident haunted Hale. He had been surveilling a car bomb maker when his superiors became concerned their subject was fleeing to Pakistan. It was their last chance to kill him.

As the bomb maker was driving, the decision was made to fire on his car. It was a cloudy day. The missile missed the car. Hale watched in real time as the man pulled over and got out. But someone else exited the car as well: a woman, his wife.

Hale had no idea their target wasn’t alone. She pulled something out of the car and left it behind as they sped off, but Hale couldn’t make out what it was from the drone camera before it moved on. Days later, Hale learned what was left behind: her two daughters, age five and three. The five-year-old had died from shrapnel wounds after the missile attack on the car; the younger sibling was severely dehydrated but still alive. Hale recounts that his commanding officer had expressed disgust at this incident, but “not for the fact that we had errantly fired on a man and his family, having killed one of his daughters.”

When reflecting on this incident, which Hale recalls whenever someone justifies drone warfare, he asks himself, “How could I possibly continue to believe that I am a good person, deserving of my life and the right to pursue happiness?”

A crisis of conscience

Barack Obama had joked about killing the Jonas Brothers with drones at a 2010 White House Correspondents’ Dinner. But by May 2013, mounting controversy about the program, especially after the killing of a U.S. citizen, meant that Obama was forced to make substantive remarks. As it happened, Hale was at a farewell party for those soldiers who, like him, would soon be returning home and leaving the Air Force. Yet Hale was “transfixed” by Obama on television.

Obama assured Americans the drone program was fine, as “near-certainty” was taken that civilians would not be killed in a strike, and only someone who was an “imminent threat” would be targeted with lethal force. Hale “came to believe that the policy of drone assassination was being used to mislead the public that it keeps us safe,” and that his “participation in the drone program [had] been deeply wrong.”

And what was all of this for? The U.S. government claims it was to keep us safe from terrorism, but as Hale watched the war unfold in Afghanistan, he “became increasingly aware that the war had very little to do with preventing terror from coming into the United States and a lot more to do with protecting the profits of weapons manufacturers and so-called defense contractors.” As Hale wrote in his letter to the judge:

“It did not matter whether it was, as I had seen, an Afghan farmer blown in half, yet miraculously conscious and pointlessly trying to scoop his insides off the ground, or whether it was an American-flag-draped coffin lowered into Arlington National Cemetery to the sound of a twenty-one-gun salute. Bang, bang, bang. Both serve to justify the easy flow of capital at the cost of blood—theirs and ours. When I think about this, I am grief-stricken and ashamed of myself of the things that I’ve done to support it.”

Hale soon became involved with antiwar activism, speaking alongside Scahill at an event and at the activist group CODEPINK’s Drone Summit. Present at the summit were family members of those killed by U.S. drones. Hale apologized to them.

One speaker, Fazil bin Ali Jaber, traveled all the way from Yemen to tell of the drone strike that killed his brother and cousin. As Fazil recounted the story, Hale sat in the audience. On the day of that strike, Hale had been on duty in Afghanistan, where he watched the entire ordeal unfold on a computer screen.

Hale hated the idea of “taking advantage of my military background to land a cushy desk job,” but he couldn’t say no to a job offer from defense contractor Leidos. Soon, despite his public antiwar activism, Hale was hired at the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), adding data to government maps of China. Socializing after work, Hale’s coworkers elected to watch videos of lethal drone strikes—for entertainment. As Hale recounted, such viewing of “war porn” had also been commonplace among soldiers in Afghanistan.

Hale was rocked by a crisis of conscience, finally concluding that “to stop the cycle of violence, I ought to sacrifice my own life and not that of another person.” It was then that Hale contacted an investigative reporter he had a relationship with—presumably Scahill—and “told him that I had something the American people needed to know.”

At the sentencing, Hale further expounded on his views. He explained to the judge that he believed killing was always wrong, hence his opposition to the death penalty, but that “killing the defenseless was especially wrong.” In response to claims his disclosures harmed national security, he brought up the fact that Pulse nightclub shooter Omar Mateen cited the killing of innocents by U.S. bombings on a phone call to police. While nothing could justify his murderous actions, it was clear that terrorism spawned as a result of U.S. policy also weighed heavy on Hale’s conscious.

Hale made it clear to the judge exactly why he was in the docket.

“I am here because I stole something that was never mine to take: precious human life. I couldn’t keep living in a world in which people pretend that things weren’t happening that were. Please, your honor, forgive me for taking papers instead of human lives.”

A farce of a trial

The proceedings against Daniel Hale were farcical from start to finish. Had he gone to trial, Hale would have been prohibited from challenging the classification of the documents he disclosed, mentioning how common leaks were and how rarely they were prosecuted, bringing up his “good motives” for disclosing the documents, or even asserting that someone else could have committed the crime unless he could name a specific person with access to the documents and a relationship with the journalist who published them.

After being stripped of any meaningful chance for a defense, Hale pled guilty to one of the five counts against him. He did so without any promise of a plea bargain. Usually under such circumstances, prosecutors would move to dismiss the remaining charges. Yet in Hale’s case, the prosecution refused to do so, meaning they could potentially force Hale to go to trial on the remaining charges if the judge’s sentence failed to satiate their vindictiveness (the remaining charges were dismissed with prejudice after sentencing). The prosecution was hell-bent on making an example out of Hale by throwing the book at him, to dissuade other future, potential whistleblowers.

Hale was initially released on his own recognizance pending sentencing. But one day, his probation officer summoned him for what Hale thought was a routine visit. Instead, Hale was taken into custody. A court-appointed therapist had expressed concern about Hale’s mental health, putting Hale in violation of the terms of his supervised release. Out of supposed concern for Hale’s mental well-being, he was locked away—in solitary confinement. Given what we know about the deleterious effects of solitary confinement on mental health, this was a particularly perverse move.

On top of that, according to the defense’s sentencing memo, the William G. Truesdale Adult Detention Center where Hale was held did not have counseling services. So, Hale’s detention, supposedly for his mental well-being, disrupted his ability to access counseling.

In the run-up to sentencing, Hale’s defense sought to force the government to disclose whether they actually had evidence that Hale’s drone disclosures caused harm to soldiers or anyone else. The government chafed at this request, arguing that they were not required to show someone actually harmed national security to prove someone violated the Espionage Act. The defense responded that, while it may not be required to garner a conviction, it is relevant in determining a sentence. One does not have to physically harm someone to be guilty of assault, but whether an assault caused grave physical injury would certainly factor into what sentence was given.

The judge ruled for the prosecution. Although the prosecution successfully fought not to turn over evidence of harm to the defense, they argued that Hale’s refusal to accept that his actions caused “exceptionally grave damage” justified imposing a longer sentence.

The prosecution made an all-out effort to demonize Hale. Hale had always insisted he was not the story, fearing that a focus on him would distract from victims of drone attacks. His friends had to stage an intervention to get him to see how his case had ramifications for other whistleblowers. While Hale appears in Sonia Kennebeck’s documentary, “National Bird,” he was working as a dishwasher and living in relative obscurity at the time of his 2019 arrest.

Yet according to prosecutors, Hale’s actions were driven by “vanity.” Hale viewed journalists as “rock stars.” In the prosecution’s version of events, Hale decided to obtain employment at the NGA with the intent of stealing documents, in order to impress a journalist and further his own nonexistent journalism career. (As the defense pointed out, given that he was working on spatial mapping of China, Hale had no idea he would have access to a computer containing classified information about the U.S. drone program, thus making the premeditation theory implausible.) The prosecution also, in one document, compared Hale to a heroin dealer who argued his distribution of narcotics aided the community. During the sentencing hearing, the prosecution flat-out asserted that Hale had aided ISIS.

The prosecution—led by Gordon Kromberg, who has gained infamy for being at the center of a number of controversial national security prosecutions, making troubling remarks about Muslim Americans, and referring to the occupied Palestinian West Bank as “Judea and Samaria”—sought a sentence of at least nine years. This would have been the longest sentence ever given for disclosing information to the media by a civilian court. If served in full, it would have been the longest sentence ever served for that crime.

The prosecution’s justification rested not just on their demonization of Hale or the fact that he believed his actions were “legally wrong, but morally right.” They made clear that this draconian sentence was needed because past prosecutions had failed to deter future whistleblowers. They wanted no more people of conscience to come forward.

This demonization of whistleblowers is a standard prosecution trick. Oftentimes, it works. Yet the judge in Hale’s case surprised many with some of his remarks. When sentencing Hale, he started off by noting the outpouring of letters he received, especially those from veterans and journalists. Judge O’Grady acknowledged that many people believe Hale to be courageous and conscientious, then affirmed his own feelings about that belief. O’Grady’s statements seemed to accept Hale was a whistleblower and that the drone program was resulting in unnecessary civilian deaths.

Yet, the judge argued, Hale could have been a whistleblower without giving documents to a journalist. In the judge’s mind, it was the giving of documents, not the speaking out against the drone war, that was a crime and the reason why Hale was here.

The Espionage Act makes no distinction between spies who steal information for hostile foreign governments and government employees who share information of public interest with the press, journalists, or even members of the public. It broadly criminalizes the unauthorized sharing or retention of “national defense information.”

The letter of the law requires an individual to have “reason to believe” their actions would harm national security, but the courts have virtually read this requirement out of the law. Because the government says the release of classified information could harm national security, the legal reasoning goes, any government employee who releases classified information has reason to believe their actions will be harmful.

The government is not required to prove a whistleblower intended to harm national security, nor is it even required to prove such harm occurred. In fact, the government argues—and the courts agree—that the documents do not even need to have been properly classified. Therefore, any giving of classified information to a journalist violates the Espionage Act. Given that the crime itself is the disclosure, the contents of the documents, the public interests served by their release, and the whistleblower’s motives for their disclosure are irrelevant. Juries are barred from hearing about them.

The Espionage Act was passed during World War I. According to human rights attorney and Espionage Act expert Carey Shenkman, the first two thousand people prosecuted under the act were prosecuted for simply opposing the war. Later Supreme Court rulings would make such prosecutions impossible, but the Espionage Act would continue to loom large over free speech.

During the McCarthy era, the act was again amended. As support flagged for his floundering conspiracy theories about traitors in the State Department, Senator Joseph McCarthy singled out the case of a failed attempt to prosecute a State Department official for allegedly giving information to a leftist foreign affairs journal that was widely read in government. The offense Hale pled guilty to was the product of these amendments. During the Vietnam War, it was used in an attempted prosecution of Daniel Ellsberg and Anthony Russo for liberating the Pentagon Papers.

For decades, the law sat mostly dormant—until the “war on terror.” As the U.S. government journeyed to the dark side, embracing surveillance, extrajudicial executions, torture, and the types of war crimes that are the hallmarks of protracted military occupations, conscientious whistleblowers came forward to the press. The Espionage Act became the go-to weapon to silence them.

Daniel Hale’s prosecution was fundamentally political. All prosecutions of whistleblowers under the Espionage Act are. Leaking of government secrets, especially to influence policy, is “a routine aspect of government life.” Government workers leak information all the time, and the vast majority of them are not punished anywhere near as severely as Hale. His crime was not leaking secrets, but the specific secrets he leaked: exposing the official U.S. proclamations about the drone program as lies.

In spite of a judge’s assertion to the contrary, it is precisely Hale’s opposition to the U.S. drone program that has condemned him to three years and nine months in a federal prison. Hale had seen firsthand what it means to kill by remote control. And he watched our government lie about it—lie that the killing was sanitary, that it was precise, that it kept us safe. Could anything justify such senseless violence? The U.S. government justifies it by citing national security concerns, but, as Hale came to learn, a more central motivation was to line the pockets of weapons manufacturers. It was murder for profit.

Hale was willing to risk his own freedom to tell us this story. And this is what the government seeks to conceal from us by turning the Espionage Act into a cudgel against truth-tellers.

Hale’s revelations did not damage national security. His prosecution, however—like the wars and cult of secrecy it was intended to protect—damaged our democracy.

—Jacobin, August 5, 2021

https://jacobinmag.com/2021/08/daniel-hale-drone-whistleblower-sentencing-trial?mc_cid=8a8e61d10f&mc_eid=49b76e976c

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

A slowdown in the network, which influences weather far and wide, could spell trouble. “We’re poking a beast,” one expert said. “But we don’t really know the reaction we’ll cause.”

By Heather Murphy, Aug. 5, 2021

Miami, where the Gulf Stream passes relatively close to the coastline. Credit...Wilfredo Lee/Associated Press

The water in the Atlantic is constantly circulating in a complex pattern that influences weather on several continents. And climate scientists have been asking a crucial question: Whether this vast system, which includes the Gulf Stream, is slowing down because of climate change.

If it were to change significantly, the consequences could be dire, potentially including faster sea level rise along parts of the United States East Coast and Europe, stronger hurricanes barreling into the Southeastern United States, reduced rainfall across parts of Africa and changes in tropical monsoon systems.

Now, scientists have detected the early warning signs that this critical ocean system is at risk, according to a new analysis published Thursday in the scientific journal Nature Climate Change.

“I showed that this gradual slowing down of the circulation system is associated with a loss of stability,” said Niklas Boers, a researcher at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany, “and the approaching of a tipping point at which it would abruptly transition to a much slower state.”

Alex Hall, the director of the Center for Climate Science at the University of California, Los Angeles, who was not involved in the study, said that although the findings did not signal to him that any collapse of that ocean system might be imminent, the analysis offered a crucial reminder of the risks of interfering with currents.

“We’re poking a beast,” he said. “But we don’t really know the reaction we’ll cause.”

Studying ocean systems is difficult for many reasons. One challenge is that there’s only one Earth, said Andrew Pershing, director of climate science at Climate Central, an organization of scientists and journalists focused on climate change. Consequently, researchers can’t easily compare two oceans — one ocean dealing with the effects global warming caused by increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and another ocean that hasn’t had to contend with that problem.

Dr. Pershing praised the analytical workarounds that the scientists came up with in order to study the ocean-spanning tangle of currents, which are known as Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC. By parsing more than a century of ocean temperature and salinity data, Dr. Boers showed significant changes in multiple indirect measures of AMOC’s strength.

“The work is fascinating,” he said.

Dr. Pershing said that analysis supported the idea that the AMOC has gotten weaker over the course of the 20th century. It’s a critical area to study because AMOC epitomizes the idea of climatic “tipping points” — hard-to-predict thresholds in Earth’s climate system that, once crossed, have rapid, cascading effects far beyond the corner of the globe where they occur.

“The big challenge is, what do we do with that information?” he said of the new study.

Susan Lozier, a physical oceanographer and dean at the College of Sciences at Georgia Tech, said that there was no doubt that climate change is affecting oceans. There is wide consensus in her field that sea levels are rising and oceans are warming, she said.

She also called Dr. Boers’ study “interesting,” but said she wasn’t convinced that the findings showed that circulation in that ocean system is slowing. “There are lots of things to worry about with the ocean,” she said, such as the more definitive concerns involving sea-level rise.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Relentless waves of the virus, combined with crises caused by conflict and climate change, have left tens of millions of people around the world on the brink of famine.

By Christina Goldbaum, Photographs by Joao Silva, Aug. 6, 2021

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/06/world/africa/covid-19-global-hunger.html?action=click&module=Well&pgtype=Homepage§ion=World%20News

Thembakazi Stishi, left, at her home. When she lost her father to Covid-19, she also lost her main source of food.

EAST LONDON, South Africa — Even as thousands died and millions lost their jobs when the Covid-19 pandemic engulfed South Africa last year, Thembakazi Stishi, a single mother, was able to feed her family with the steady support of her father, a mechanic at a Mercedes plant.

When another Covid-19 wave hit in January, Ms. Stishi’s father was infected and died within days. She sought work, even going door to door to offer housecleaning for $10 — to no avail. For the first time, she and her children are going to bed hungry.

“I try to explain our situation is different now, no one is working, but they don’t understand,” Ms. Stishi, 30, said as her 3-year-old daughter tugged at her shirt. “That’s the hardest part.”

The economic catastrophe set off by Covid-19, now deep into its second year, has battered millions of people like the Stishi family who had already been living hand-to-mouth. Now, in South Africa and many other countries, far more have been pushed over the edge.

An estimated 270 million people are expected to face potentially life-threatening food shortages this year — compared to 150 million before the pandemic — according to analysis from the World Food Program, the anti-hunger agency of the United Nations. The number of people on the brink of famine, the most severe phase of a hunger crisis, jumped to 41 million people currently from 34 million last year, the analysis showed.

The World Food Program sounded the alarm further last week in a joint report with the U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization, warning that “conflict, the economic repercussions of Covid-19 and the climate crisis are expected to drive higher levels of acute food insecurity in 23 hunger hot spots over the next four months,” mostly in Africa but also Central America, Afghanistan and North Korea.

The situation is particularly bleak in Africa, where new infections have surged. In recent months, aid organizations have raised alarms about Ethiopia — where the number of people affected by famine is higher than anywhere in the world — and southern Madagascar, where hundreds of thousands are nearing famine after an extraordinarily severe drought.

For years, global hunger has been steadily increasing as poor countries confront crises ranging from armed groups to extreme poverty. At the same time, climate-related droughts and floods have intensified, overwhelming the ability of affected countries to respond before the next disaster hits.

But over the past two years, economic shocks from the pandemic have accelerated the crisis, according to humanitarian groups. In rich and poor countries alike, lines of people who have lost their jobs stretch outside food pantries.

As another wave of the virus grips the African continent, the toll has ripped the informal safety net — notably financial help from relatives, friends and neighbors — that often sustains the world’s poor in the absence of government support. Now, hunger has become a defining feature of the growing gulf between wealthy countries returning to normal and poorer nations sinking deeper into crisis.

“I have never seen it as bad globally as it is right now,” Amer Daoudi, senior director of operations of the World Food Program, said describing the food security situation. “Usually you have two, three, four crises — like conflicts, famine — at one time. But now we’re talking about quite a number of significant of crises happening simultaneously across the globe.”

In South Africa, typically one of the most food-secure nations on the continent, hunger has rippled across the country.

Over the past year, three devastating waves of the virus have taken tens of thousands of breadwinners — leaving families unable to buy food. Monthslong school closures eliminated the free lunches that fed around nine million students. A strict government lockdown last year shuttered informal food vendors in townships, forcing some of the country’s poorest residents to travel farther to buy groceries and shop at more expensive supermarkets.

An estimated three million South Africans lost their jobs and pushed the unemployment rate to 32.6 percent — a record high since the government began collecting quarterly data in 2008. In rural parts of the country, yearslong droughts have killed livestock and crippled farmers’ incomes.

The South African government has provided some relief, introducing $24 monthly stipends last year and other social grants. Still by year’s end nearly 40 percent of all South Africans were affected by hunger, according to an academic study.

In Duncan Village, the sprawling township in Eastern Cape Province, the economic lifelines for tens of thousands of families have been destroyed.

Before the pandemic, the orange-and-teal sea of corrugated metal shacks and concrete houses buzzed every morning as workers boarded minibuses bound for the heart of nearby East London. An industrial hub for car assembly plants, textiles and processed food, the city offered stable jobs and steady incomes.

“We always had enough — we had plenty,” said Anelisa Langeni, 32, sitting at the kitchen table of the two-bedroom home she shared with her father and twin sister in Duncan Village.

For nearly 40 years, her father worked as a machine operator at the Mercedes-Benz plant. By the time he retired, he had saved enough to build two more single family homes on their plot — rental units he hoped would provide some financial stability for his children.

The pandemic upended those plans. Within weeks of the first lockdown, the tenants lost their jobs and could no longer pay rent. When Ms. Langeni was laid off from her waitressing job at a seafood restaurant and her sister lost her job at a popular pizza joint, they leaned on their father’s $120 monthly pension.

Then in July, he collapsed with a cough and fever and died of suspected Covid-19 en route to the hospital.

“I couldn’t breathe when they told me,” Ms. Langeni said. “My father and everything we had, everything, gone.”

Unable to find work, she turned to two older neighbors for help. One shared maize meal and cabbage purchased with her husband’s pension. The other neighbor offered food each week after her daughter visited — often carrying enough grocery bags to fill the back of her gray Honda minivan.

But when a new coronavirus variant struck this province in November, the first neighbor’s husband died — and his pension ended. The other’s daughter died from the virus a month later.

“I never imagined it would be like this,” that neighbor, Bukelwa Tshingila, 73, said as she wiped her tear-soaked cheeks. Across from her in the kitchen, a portrait of her daughter hung above an empty cupboard.

Two hundreds miles west, in the Karoo region, the pandemic’s tolls have been exacerbated by a drought stretching into its eighth year, transforming a landscape once lush with green shrubs into a dull, ashen gray.

Standing on his 2,400-acre farm in the Karoo, Zolile Hanabe, 70, sees more than his income drying up. Since he was around 10 and his father was forced to sell the family’s goats by the apartheid government, Mr. Hanabe was determined to have a farm of his own.

In 2011, nearly 20 years after apartheid ended, he used savings from working as a school principal to lease a farm, buying five cattle and 10 Boer goats, the same breed his father had raised. They grazed on the shrubs and drank from a river that traversed the property.

“I thought, ‘This farm is my legacy, this is what I will pass onto my children,’” he said.

But by 2019, he was still leasing the farm and as the drought intensified, that river dried, 11 of his cattle died, the shrubs shriveled. He bought feed to keep the others alive, costing $560 a month.

The pandemic compounded his problems, he said. To reduce the risk of infection, he laid off two of his three farm hands. Feed sellers also cut staff and raised prices, squeezing his budget even more.

“Maybe one of these crises, I could survive,” Mr. Hanabe said. “But both?”

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

By Bryce Covert, August 6, 2021

On a July day in downtown Lowell, Mass., the first sunny Saturday of the month, people began to line up for a block party. Food trucks offered everyone a free empanada or egg roll. A D.J. played music. There were kid-friendly activities, too, like a touch-a-truck station with a fire truck and an ambulance.

The party wasn’t just a way to have a good time. The real motivation was to get people in the community vaccinated against Covid-19. Nestled between the food trucks were ones offering Pfizer, Moderna and Johnson & Johnson vaccines.

In the minds of the public health and community organizers who staged it, it was a roaring success. Sixty-four people got vaccinated within six hours. Hannah Tello, a community health data manager at the nonprofit Greater Lowell Health Alliance, noted that it was eight to 10 times as many vaccinations as what their mobile clinics had been doing; their most successful day before this administered 12.

The people who got shots at the party “were not people who were resistant,” Dr. Tello told me. Outreach workers went to a nearby park and invited the homeless people there to get free food and, if they wanted, a vaccination, and many took them up on the offer in such a low-stakes, nonmedical setting.

An elderly woman who cares for two people with disabilities had tried and failed to schedule vaccinations for all three of them at the same time. This time, she succeeded. A woman who was able to vaccinate all the other eligible people in her family hadn’t been able to get it herself because she has four young children she wasn’t allowed to take to the vaccination center. That day her children played cornhole while she got the shot.

The party organizers also reached about 250 other attendees, many of whom had conversations about their concerns. Some were worried that the vaccines cost money, even though they’re free to all. They were concerned they would need some sort of documentation, which they don’t. One woman hadn’t gotten the shot yet because she has an intense fear of needles; she did it that day after 25 minutes of talking it through. “Her getting her shot is just as important as the people who lined up outside our clinics a few months ago,” Dr. Tello said. “No one is less deserving of having access.”

The country’s vaccination campaign has lagged since April, and that has allowed for a spike in cases, particularly in largely unvaccinated areas. Vaccinations have risen lately in response to the spread of the Delta variant, but rather than keeping its foot on the gas and throwing every idea, every resource at the problem, the White House has started to shift the blame onto those who still haven’t gotten a shot. President Biden grumbled that he has struck a “brick wall” in persuading more Americans to get the shot. Last week, taking aim at those he called “unvaccinated, unbothered and unconvinced,” he said, “If you’re out there unvaccinated, you don’t have to die. Read the news.”

There are plenty of Americans who have been inundated with misinformation about the vaccines. Many are staunchly opposed to getting it for a variety of reasons, from personal health concerns to conspiracy theories. But that doesn’t describe everyone who is unvaccinated — not by a long shot. And there are plenty of things we can do to reach them if we’re serious about spending the time and the money.

Instead, the current approach is to argue that access has increased and it’s everyone’s individual responsibility to get a shot — and if you don’t, it’s on you. Once again, we have taken the cruelly American, ruggedly individualistic tactic of making this about personal responsibility, not about a systemic response, just as we did in combating the virus itself.

“It’s not a public health strategy for any condition to just blame somebody into treatment and prevention,” said Rhea Boyd, a pediatrician and public health advocate. Telling the unvaccinated that they’re being selfish “really runs counter to all the work it’s going to take to convince those folks to be vaccinated, to trust us that we have their best interests in mind.”

It’s also shortsighted. If some people continue to struggle with getting vaccinated, the virus will continue to run rampant, threatening a rebound in economic activity and giving the coronavirus a chance to mutate yet again. The refrain we’ve heard throughout is still true: We’re not safe until we’re all safe.

Those who aren’t yet vaccinated are much more likely to be food insecure, have children at home and earn little. About three-quarters of unvaccinated adults live in a household that makes less than $75,000 a year. They are nearly three times as likely as the vaccinated to have had insufficient food recently. Many of them have pressing concerns they can’t just put aside because they need to get a vaccination.

Access is far more widespread than it was at the beginning of the year. Many cities now offer multiple venues for getting it without needing an appointment. But about 10 percent of the eligible population still lives more than a 15-minute drive from a vaccine distribution location. And even if there’s a site down the road, it usually requires taking time off work — not just to get the shot but also potentially to recover from the side effects — arranging transportation and figuring out child care.

“Missing out on a few hours of work seems very easy to us, but in fact it could be the matter of having food for the family versus not,” said Ann Lee, the chief executive of the nonprofit Community Organized Relief Effort. For these people, when they’re weighing whether to get a vaccination or potentially forgo some wages, “the wages are going to win out.”

Those who are unvaccinated are also likely to work in essential jobs like agriculture and manufacturing that don’t allow them to step away from work. They work long hours and may prioritize time with their families or communities when they finally get a break. People who have multiple jobs may find it impossible to schedule a shot in between all of their shifts.

And yet 43 percent of the unvaccinated say they definitely or probably would get it or are unsure, according to Julia Raifman, an assistant professor at the Boston University School of Public Health.

“We pretty quickly exhausted those who were easiest to reach and vaccinate,” Tara Smith, a public health professor at Kent State, told me. “This next phase is more difficult, but I don’t think it’s impossible to continue to get more people vaccinated. We just have to get creative.”

A block party doesn’t work in every community, particularly more rural ones. For those places, an event could be staged at a church or a county fair. Anything that allows people to discuss their concerns with experts and get vaccinated on the spot erases dangerous lag time. Dr. Tello’s organization found that many disappeared in the time between an educational conversation and a vaccination appointment weeks later.

Another way to take the vaccines to people for whom the logistics are complicated is to do it at workplaces. Ms. Lee’s organization held a vaccination drive at a construction site in Washington, D.C., and vaccinated 165 people. “They wanted to get vaccinated. There was just no way some of these day laborers were going to take off of work and maybe get sick,” Ms. Lee said. In January, Riverside, Calif., began a program to take vaccines into the fields to reach agricultural workers.

There are plenty of other smart places to distribute vaccines. Take them to food pantries, where low-income and food-insecure people show up by necessity on a regular basis. Do vaccinations at shopping centers where everyone goes to buy food. Vaccine drives could also be held on the first day of school for parents and older children alike; it’s late in the game, since it takes weeks for full immunity, but it’s better than missing them entirely.

Going door to door can also reach people, particularly those who are homebound. The Central Falls Housing Authority in Rhode Island offered shots to its public housing residents at the end of last year, and by January, 80 percent had been vaccinated. In Los Angeles, Ms. Lee’s team contacts the homebound first to talk through any concerns and again a week later to administer a vaccine. Vaccines could even be paired with Meals on Wheels deliveries.

To address transportation issues, the White House collaborated with Uber and Lyft to give free rides up to $25 to and from vaccination sites. But those companies don’t operate in every community, particularly outside cities. The government could also give grants to community organizations that can give people free rides to vaccination sites. “If you have a bus at a church, you can get a grant,” Dr. Boyd suggested.

We have to mandate paid leave so workers can take at least two days to get a shot and recover without jeopardizing their incomes. The Biden administration has offered tax credits to employers with fewer than 500 employees to cover the cost of offering paid leave for getting vaccinated, which he expanded this month. Some states, including New York, have mandated it. But everywhere else, it’s up to an employer to offer it, and if existing paid leave benefits are any guide, it’s the lowest-wage workers who are least likely to get it. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration released an emergency temporary standard in June that requires employers to provide paid time off to get vaccinated and recover, but it applies only to health care workers, despite the fact that a draft version included everyone.

Short of that, community organizations can send people home from getting vaccinated with enough food for their families if they have to miss work for a day or two. When Ms. Lee’s organization did testing in the Navajo Nation, it gave people two weeks of food in case they got a positive result and had to quarantine. It’s now sending people home with food as well as diapers, formula and hygiene kits with things like shampoo and tampons.

Parents also need child care — not just for getting their shots but also if they experience side effects. The government is working with four large child care providers to offer free care, but those centers may not be available to everyone, nor will all parents feel comfortable sending their children to an unfamiliar setting. Instead, we could give them money to pay their trusted source of child care and also offer care at vaccination centers.

State and local officials can kick-start some of this on their own. But the real money, and the power to set the agenda, comes from the White House and Congress. “If the federal government said, ‘We are really concerned, we see that low-income people have not had access to the vaccine, and we’re putting forth a huge effort to bring it to them in their workplaces and homes,’” Dr. Raifman said, “that would be a compelling message that would mobilize people across the country.” Federal funding needs to be filtered down to the local level as quickly as possible. There’s a lot of money for vaccinations, but it has to get to the organizations that are deeply embedded in their communities and ready to pull this off.

Dr. Tello’s organization plans to repeat the block party this summer, this time as a back-to-school event, handing out free backpacks and school supplies as well as flu shots alongside the Covid vaccines. And it will be timed so that those who got their first shot of the Moderna or Pfizer vaccine at July’s party can get their second dose on the spot. “Sometimes,” she said, “you have to make it too convenient so that people can’t say no.”

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Exporting soldiers has become a vast industry in Colombia, fueled by the country’s long U.S.-backed war, limited opportunity at home and growing demand abroad.

“Colombia’s modern civil conflict was ignited by the assassination of a left-wing presidential candidate in 1948. Over time, the conflict grew into a complex war between the government, left-wing insurgents, right-wing paramilitaries and drug-trafficking organizations, all while Colombia received billions of dollars in military support from the United States, its staunch ally.”