With just one week to go until the next coordinated day of solidarity actions with Bessemer Amazon workers, demonstrations are set from coast to coast. Find an initial listing of actions below, and let us know what you're planning in your area here, or submit an endorsement.

Amazon is pulling out all the stops to try to prevent this historic campaign led by Black workers from succeeding, spending tens of millions of dollars to wage an aggressive union-busting campaign. March 20 will send a message loud and clear to denounce Amazon's union busting, and to let the workers in Bessemer know (and Amazon and workers everywhere!) that there is a movement behind them. The weekend of March 20 is also the U.N. Anti-Racism Day, and the actions will further draw the connection between the fight against racism and for worker power.

Join this growing day of action by planning an event in your area. In different cities, workers and community activists are planning rallies, pickets, gathering neighbors and coworkers to hold signs in front of Whole Foods or Amazon warehouses, distributing leaflets, and more. Each action is significant, regardless of how large it may be. We've also added new materials to use to build for March 20 and at your events, including graphics that can be customized with your local activity.

We're also very excited to announce a special webinar coming up this Tuesday, March 16, at 8pm eastern featuring renowned scholar-activist Dr. Robin D.G. Kelley. Dr. Kelley is the author of "Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists During the Great Depression," and will join us to discuss the history and significance of the BAmazon Union struggle and it's connections to the period analyzed in his book. Dr. Kelley has also endorsed the call for actions on March 20. Register for this event here:

https://us02web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_VxGc8C6JR2SQ4n_-Nwqa9Q

Saturday, March 20, 2021

SAN FRANCISCO, CA

10:00 A.M. Picket & Speak-Out

7th & Berry Street, San Francisco, CA

Contact United Front Committee for a Labor Party

committeeforlaborparty@gmail.com

415-533-5642

OAKLAND, CA

1:00 P.M. Car Caravan & Rally

Oscar Grant Plaza/Frank Ogawa Plaza 14th & Broadway, Oakland, CA

Contact Support Amazon Workers – Bay Area

bayarea@supportamazonworkers.org

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Join us Thursday, March 25th for an International Women's Month conversation with four courageous women who have stood up for their lives and their communities.

Register here: bit.ly/DefendOurLives

After registering, you will receive a confirmation email containing information about joining the meeting.

• Janet and Janine Africa - the MOVE 9

• Siwatu Salama Ra - Freedom Team Detroit/Grassroots Global Justice

• Laura Whitehorn - RAPP (Release Aging People in Prison)

• *Possible surprise speaker!

• Moderated by Aleta Toure' - Parable of the Sower Intentional Community Cooperative, Grassroots Global Justice (GGJ), People's Strike, and AfroSoc

Spread the word on Facebook!

*In the event that registration is full, join via Facebook live

Across the U.S. and the globe, unprecedented health, economic and social crisis is leading to escalating violence against BIPOC communities, often targeting women and TGNC people in particular. Over 10,000 people were arrested in the course of the 2020 uprisings after George Floyd's murder, but they have largely been disappeared from public view. Women who have been imprisoned for defending themselves and their communities have much to teach us about resisting state violence.

Hosted by California Coalition for Women Prisoners and Parable of the Sower Intentional Community Cooperative

Endorsed by: The National Jericho Movement, New York City Jericho Movement, Release Aging People in Prison, Aging People in Prison - Human Rights Campaign, Oakland Jericho Movement, Freedom Archives, and Grassroots Global Justice, Critical Resistance

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Shut Down Adelanto Coalition puts ICE on Trial!

Saturday, March 28th, 12:00 P.M.

There will be testimony from impacted folks, expert testimony, and more.

More information to follow about who is scheduled to speak, the judges, and the length of the program.Please save the date + RSVP for the virtual People’s Tribunal at 12pm on Sunday March 28th here!

https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSeP69t5zwdkgnK-kNOhemVGcHW6poO4B6x5Pquyhpn92yYuow/viewform

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

INNOCENT AND FRAMED - FREE MUMIA NOW!

NO STATE EXECUTION BY COVID!

NO ILLUSIONS IN “PROGRESSIVE” DA LARRY KRASNER!

The movement to Free Mumia Abu-Jamal, the most prominent political prisoner in the U.S., from the slow death of life imprisonment and the jaws of this racist and corrupt injustice system is at a critical juncture. The battle to free Mumia must be is as ferocious as it has ever been. We continue to face the unrelenting hostility to Mumia by this racist capitalist injustice system, which is intent on silencing him, by all means.

Mumia is at immediate risk of death by covid! Mumia has tested positive for covid-19. The PA Department of Corrections and officials at SCI Mahanoy at first denied this, but then needed to hospitalize Mumia. He is now in the prison infirmary. Mumia’s life is on the line. He is almost 67 years old; his immune system is compromised because of liver cirrhosis from years of untreated hepatitis-C. It is also reported that Mumia now has congestive heart failure!

An international campaign succeeded in getting a judicial order that Mumia was deprived of essential health care and be treated with life-saving Harvoni treatment. That has compelled the DOC to provide the medication to Mumia and other prisoners infected with hep-C.

The National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA) said it best, “The refusal of health-care reminds us of the conditions we were put in under Apartheid prisons where sick detainees were allowed to die in very deplorable lonely conditions in solitary as part of the punishment for their role in the struggle.”

We, in the Free Mumia movement, call on all to ACT NOW! Mumia must not die in prison from covid! He should be released, now!

Urgent: Email Gov. Tom Wolf, brunelle.michael@gmail.com; John Wetzel, Secretary PA Department of Corrections, jwetzel@state.pa.us and ra-crpadoc.secretary@pa.gov.

Demand: Mumia Abu-Jamal Must be Released from Prison! No State Execution by Covid! Prisoners 50 Years and Older Should also be Released from Prison to Protect them from Covid 19!

Mumia’s life was saved from legal lynching of state execution in 1995 and 1999 by the power of mass, international mobilization and protest, which included representatives of millions of unionized workers. Human and civil rights organizations, labor unions, and students won Mumia’s release from death row in 2012 and his medical treatment for deadly hep-C in 2017. Now we need to do the same to save his life from covid-19.

We also must face the latest obstacle in Mumia’s pending legal appeal.

In the prosecution Response to Mumia’s appeal to the Pennsylvania Superior Court, filed February 3, 2021, “progressive” District Attorney Larry Krasner rubber stamps the lying, racially biased, politically motivated and corrupt conviction of Mumia for the murder of P.O. Daniel Faulkner on December 9, 1981 under hanging judge Albert Sabo who promised, “I’m going to help them fry the nigger.”

For decades Mumia fought racist and corrupt prosecutors in Pennsylvania state court and the U.S. federal court. “Progressive” Philadelphia D.A. Larry Krasner joined their ranks in filing the prosecution legal brief to the Pennsylvania Superior Court stating that Mumia is guilty and should remain imprisoned for life.

.

There is a moment of opportunity to deepen the struggle for Mumia’s freedom. Political consciousness about the systemic racism of the U.S. injustice system and policing has reached a high level not seen in 50 years, accelerated by the police murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and so many others, and the massive protests that followed. Mumia’s name has been injected into struggles around Black Lives Matter, the pandemic and the economic crisis. Notably, Colin Kaepernick has called for Mumia’s freedom.

There is also a new danger. Nationally and in Philadelphia, there is a rise in the illusions of the “progressive district attorney” who will upend the entrenched repressive, racially and class-biased [in]justice system, which is integral to capitalism and rooted in the legacy of slavery.

A new legal path to Mumia’s freedom was opened by the historic ruling in December 2018 from Philadelphia Court Judge Leon Tucker, the first Black jurist to review Mumia’s case. Judge Tucker granted Mumia the right to file a new appeal of all the evidence of judicial, prosecutorial and police misconduct that had been rejected by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court from 1998-2012. That evidence was proof that Mumia is factually innocent and framed and is legally entitled to dismissal of the charges against him, or at least a new trial.

“Progressive” DA Larry Krasner blocked that path with the prosecution’s legal Response to Mumia’s new appeal to the PA Superior Court on February 3, 2021. Krasner opposes Mumia getting a new trial—let alone a dismissal of the charges. And Krasner calls for the appeals court to dismiss Mumia’s appeal without even considering the facts and law. Krasner follows exactly the script of the notorious, pro-cop, racist prosecutors who preceded him, notably Edward Rendell, Lynne Abraham—called “one of America’s deadliest DAs” —and Ronald Castille, whose pro-cop, pro-prosecution, and pro-death penalty bias became the grounds opening up Mumia’s right to file this new appeal.

The Krasner Response begins with the same lying “statement of facts” of the case that has been used since Mumia’s 1982 frame-up trial by District Attorney Edward Rendell. Krasner insists that Mumia’s appeal should be dismissed without considering the merits because it was “not timely filed.” This makes clear the falsity of Krasner’s purported withdrawal of his objection to Mumia’s new right of appeal granted by Judge Tucker.

Krasner also denies that the newly disclosed evidence of state misconduct—“Brady claims”—from the six hidden boxes of Mumia’s prosecution files found two years ago in a DA storeroom are “material” and grounds for a new trial. This is legal jargon for saying the evidence against Mumia at trial was so overwhelming that it wouldn’t have made a difference to the jury that convicted him of first degree murder and sentenced him to death. Krasner’s Response on the new evidence that the trial prosecutor purposely disqualified African-Americans as jurors is that the Pa Supreme Court has previously decided the jury selection process was fair and should not be re-examined.

As District Attorney, Krasner had the legal authority and responsibility to review Mumia’s case and, as constitutionally warranted, to support overturning Mumia’s conviction because of due process violations and state misconduct. Those due process violations included:

*trial and post-conviction judge Sabo was biased and racist

*African-Americans were excluded from juries as a policy and practice of the Philadelphia DA’s office

*police and prosecutorial misconduct in presenting false witness testimony that Mumia shot Faulkner, a fabricated confession and a manufactured scenario of Mumia shooting PO Faulkner which is disproved by ballistics, medical, and other forensic evidence, including photographs of the crime scene; and

*the suppression of witnesses who swore that Mumia did not shoot PO Faulkner, that a shooter ran away and the confession to fatally shooting Faulkner.

But “progressive” DA Krasner argued these factors should not even be considered.

DA Krasner’s Response brief ends with: “For the foregoing reasons, including those set forth in the PCRA court’s opinions, the Commonwealth respectfully requests that this Court affirm the orders denying post-conviction relief.” This means District Attorney Krasner approved all previous court denials of Mumia’s challenges to his convictions made from 1995-2012, including those of Judge Sabo.

This Response is the definitive, final statement of District Attorney Larry Krasner to the Superior and Supreme Courts of Pennsylvania. And should Mumia’s case return to the U.S. federal courts, this would remain the prosecution position: that Mumia is guilty and there are no legal or factual reasons to re-consider his conviction.

Once there has been a conviction and sentence, the District Attorney does not have unilateral authority or power to reverse a criminal conviction, order a new trial or dismiss the original charges. That decision rests the post-conviction review judge or appeals court.

The District Attorney does have enormous authority and credibility to argue to the courts that a case should be reversed, a new trial granted or charges dismissed. The opinion of the district attorney’s office is a persuasive authority to the reviewing court. And it was that process which resulted in overturning the convictions of 18 imprisoned men during the past three years. Those publicized reversals as well as Krasner’s promises of criminal justice reform; his “no objection” to releasing on parole the surviving, imprisoned MOVE 9 men and woman; his partial ban of cash bail and de-escalation of arrests for minor, non-violent offenses, and his record as a civil rights lawyer gave him credentials as a “progressive DA”.

Krasner’s Response to Mumia’s appeal is an undeniable legal blow and has most likely blocked the judicial path to Mumia’s freedom.

To any who held out hope that Krasner would “do the right thing”, Krasner has never given any indication that he questioned Mumia’s conviction, even when—after protest and pressure—he agreed not to oppose the appeal process.

In fact, “progressive DA” Krasner was explicit when questioned during the proceedings brought by Maureen Faulkner to have him removed from Mumia’s case on grounds he was biased in favor of Mumia. Krasner was allowed to continue prosecuting Mumia in the Supreme Court ruling on December 16, 2020. During those proceedings, Larry Krasner assured the investigating judge that, “in my opinion based upon all the facts in law [sic] that I have is that he [Abu-Jamal] is guilty.” Further, the investigating judge found all prosecutors involved, including DA Krasner, stated, “it is their intention to defend the conviction, and that they are aware of no evidence that would support or justify a decision to the contrary or to concede any PCRA relief.”

It is precisely because Larry Krasner has a profile and reputation as “a progressive DA,” and faces hostility from the Fraternal Order of Police, and supporters of racist “law and order” who will be supporting anti-Krasner candidates in this year’s DA election that his total rejection of Mumia’s claim is so damaging.

The rejection of Mumia’s appeals by this “progressive DA” is not just equal to those of prior DAs but is more damaging. The position of the “progressive DA” in opposition to Mumia’s appeal provides additional rationale and justification for the appeals courts to reject Mumia’s appeals.

Krasner must be uncompromisingly exposed and denounced as not different from Judge Sabo and prior prosecutors. Mumia’s prosecution, his conviction, death sentence and appeal denials are an indictment of the entire racist capitalist injustice system. Opening up Mumia’s case exposes the racism, rot, corruption, brutality and fundamental injustice of the whole system. “Progressive” district attorney Larry Krasner would not and cannot go down that road and keep favor with the elements of the ruling class that seek to provide a “progressive” cover to delay and distract those who fight not only for Mumia, but for justice for all.

What is to be done to free Mumia? Continue to mobilize protest action demanding the Department of Corrections and Governor immediately release Mumia – along with prisoners 50 years and older to stop death by covid. In Pennsylvania the governor has the executive power to commute sentences and release prisoners who are serving life without parole.

We must expand the international campaign for Mumia’s freedom, centered on the understanding that Mumia is factually innocent and framed, that he never should have been arrested and prosecuted for a murder the state knows he did not commit. International mobilization has been critical to our prior limited victories. Now more than ever, we need to grow in strength and numbers Mumia’s defenders, including labor, Black Lives Matter, human rights and civil rights organizations, and left organizations in rallies and mass demonstrations.

Rachel Wolkenstein (former attorney for Mumia Abu-Jamal); and for the Labor Action Committee to Free Mumia Abu-Jamal <laboractionmumia.org>: Jack Heyman (International Longshore and Warehouse Union-retired), Bob Mandel (Oakland Education Association-retired, member of Adult School Teachers United), Carole Seligman (Co-editor of Socialist Viewpoint)

March 5, 2021

Call the Superintendent of Mumia's Prison and demand he be taken to the hospital for treatment for COVID-19. It is not okay that they merely test him (they had not asof Fri. night), the results will take days to come back and he is experiencing chest pains & breathing problems now--and COVID requires quick medical care to avoid death.

It Is Now Freedom or Death For Mumia!

BRO. ZAYID MUHAMMAD - March 11, 2021

http://amsterdamnews.com/news/2021/mar/11/it-now-freedom-or-death-mumia/

I’m going help them fry the nigger...” Judge Albert Sabo

“There comes a time when silence is betrayal...” Martin Luther King, Jr.

Imagine all NNPA Black newspapers, for example, carrying regularly featured articles as a matter of priority on all of the evidence suppressed in Mumia’s case.

Imagine Black clergy rallying at major news sites condemning the white-out and/or the demonization of Mumia through their media entities.

Imagine Black elected officials from Philadelphia and from all over the country rallying to denounce the continued ordeal of this man.

Imagine surviving ’60s icons conducting civil disobedience at the governor’s office and the DA’s office in Philadelphia with an eager throng of two generations of action-hungry activists looking to bumrush it, en masse if it didn’t yield results.

Even though Mumia has survived two execution dates, 30 years on death row and several recent dangerous medical challenges, thankfully with the force of a multiracial international campaign at his back and our ancestors, this hasn’t happened yet.

It’s time to ask ‘why?’

As this goes to press, Mumia is in a prison infirmary dangling on a tightrope of both COVID-19 and congestive heart failure, a most deadly medical cocktail!

COVID-19 is most dangerous when it attacks the lungs, creates fluid in the lungs and then triggers fatal blood clots. Congestive heart failure, similarly speaking, creates fluid in the lungs, weakens the heart muscle and the kidneys. These two together are extremely deadly.

Not to mention Mumia’s Hep-C weakened liver and skin. Remember that?

Mumia needs to be hospitalized at minimum and truly needs to be released!

If ever there was a time to step forward for Mumia, it is now!

The most tragic dimensions surrounding Mumia’s current ordeal is that there is now so much ample evidence of his innocence, so much ample evidence of both prosecutorial and judicial misconduct to free him if he can just be allowed to get it in on an appeal and that evidence on the court record. In spite of Mumia clearly being on the verge of objectively vindicating himself, he can tragically die in prison if not enough of us turn it up now!

Wait! What about Philly’s highly prized progressive DA Larry Krasner? Hasn’t he moved to overturn more than a dozen bad convictions rooted in deep-seated Philly racism and corruption? Yes, but not for Mumia.

Even though his office ‘found’ six boxes of missing evidence in his case, which includes a letter from a star prosecution witness Robert Chobert seeking payment for his testimony, reeking of prosecutorial misconduct and granting Mumia a new trial, Krasner, up for re-election, went into court last month and said that no new appellate relief for Mumia ought to be granted because his trial and conviction were sound. From Judge Sabo vowing to help ‘fry the nigger,’ to suppressed eyewitness testimony that was not paid for by anyone totally contradicting Chobert’s, to the illegal exclusion of Black jurors from the trial, to Sabo having Veronica Jones arrested on the stand for telling the truth on how she was coerced to testify against Mumia, to their being clear evidence of another person being the actual killer of Officer Daniel Faulkner and a whole lot more, Krasner showed his true ‘white’ color and is now seeking to block Mumia’s real chance at justice and freedom at a time when it can genuinely cost him his life.

The time is now to turn it up and free this incredible human being who has become a breathing living gracious symbol of human solidarity like few others in the last several decades.

Let us all press Pennsylvania’s other liberal ‘fox’ Gov. Tom Wolf to have Mumia and all aging prisoners who pose no risk to society released to help address this insidious pandemic. Over 100 people have died from COVID-19 in Pennsylvania prisons. All over 50 and with preexisting conditions.

Let’s press Mumia’s overseers John Wetzel head of Pennsylvania Department of Corrections and Bernadette Mason superintendent of Mahanoy Prison to get Mumia properly hospitalized.

Press DA Krasner to address his now dangerous wrong and go back into court and encourage a conviction reversal and a new trial for Mumia as he has done for others.

The time is now!

Seize The Time!

Free Mumia Abu Jamal!

Gov. Tom Wolf 717-787-2500

Sec’y Dept of Corrections John Wetzel 717-728-2573

Supt of Mahanoy Corrections Institution Bernadette Mason 570-773-2158

DA Larry Krasner 267-456-1000

To support Mumia locally 212 -330-8029

In Philadelphia, 215-724-1618

Zayid Muhammad is a jazz poet, stage actor and well-known “cub” of the N.Y. chapter of the Black Panther Party.

Questions and comments may be sent to info@freedomarchives.org

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Pass COVID Protection and Debt Relief

Stop the Eviction Cliff!

Forgive Rent and Mortgage Debt!

Millions of Californians have been prevented from working and will not have the income to pay back rent or mortgage debts owed from this pandemic. For renters, on Feb 1st, landlords will be able to start evicting and a month later, they will be able to sue for unpaid rent. Urge your legislator and Gov Newsom to stop all evictions and forgive COVID debts!

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to rock our state, with over 500 people dying from this terrible disease every day. The pandemic is not only ravaging the health of poor, black and brown communities the hardest - it is also disrupting our ability to make ends meet and stay in our homes. Shockingly, homelessness is set to double in California by 2023 due the economic crisis unleashed by COVID-19. [1]

Housing is healthcare: Without shelter, our very lives are on the line. Until enough of us have been vaccinated, our best weapon against this virus will remain our ability to stay at home.

Will you join me by urging your state senator, assembly member and Governor Gavin Newsom to pass both prevent evictions AND forgive rent debt?

This click-to-call tool makes it simple and easy.

https://www.acceaction.org/stopevictioncliff?utm_campaign=ab_15_16&utm_medium=email&utm_source=acceaction

Renters and small landlords know that much more needs to be done to prevent this pandemic from becoming a catastrophic eviction crisis. So far, our elected officials at the state and local level have put together a patchwork of protections that have stopped a bad crisis from getting much worse. But many of these protections expire soon, putting millions of people in danger. We face a tidal wave of evictions unless we act before the end of January.

We can take action to keep families in their homes while guaranteeing relief for small landlords by supporting an extension of eviction protections (AB 15) and providing rent debt relief paired with assistance for struggling landlords (AB 16). Assembly Member David Chiu of San Francisco is leading the charge with these bills as vehicles to get the job done. Again, the needed elements are:

Improve and extend existing protections so that tenants who can’t pay the rent due to COVID-19 do not face eviction

Provide rent forgiveness to lay the groundwork for a just recovery

Help struggling small and non-profit landlords with financial support

Ten months since the country was plunged into its first lockdown, tenants still can’t pay their rent and debt is piling up. This is hurting tenants and small landlords alike. We need a holistic approach that protects Californians in the short-run while forgiving unsustainable debts over the long term. That’s why we’re joining the Housing Now! coalition and Tenants Together on a statewide phone zap to tell our elected leaders to act now.

Will you join me by urging your state senator, assembly member and Governor Gavin Newsom to pass both prevent evictions AND forgive rent debt?

Time is running out. California’s statewide protections will start expiring by the end of this month. Millions face eviction. We have to pass AB 15 before the end of January. And we will not solve the long-term repercussions on the economic health of our communities without passing AB 16.

ASK YOUR ELECTED OFFICIALS TO SAY YES ON AN EVICTION MORATORIUM AND RENT DEBT FORGIVENESS -- AB 15 AND AB16!!!

Let’s do our part in turning the corner on this pandemic. Our fight now will help protect millions of people in California. And when we fight, we win!

In solidarity,

Sasha Graham

[1] https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2021-01-12/new-report-foresees-tens-of-thousands-losing-homes-by-2023

ACCE Action

http://www.acceaction.org/

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Tell the New U.S. Administration - End

Economic Sanctions in the Face of the Global

COVID-19 Pandemic

Take action and sign the petition - click here!

https://sanctionskill.org/petition/

To: President Joe Biden, Vice President Kamala Harris and all Members of the U.S. Congress:

We write to you because we are deeply concerned about the impact of U.S. sanctions on many countries that are suffering the dire consequences of COVID-19.

The global COVID-19 pandemic and global economic crash challenge all humanity. Scientific and technological cooperation and global solidarity are desperate needs. Instead, the Trump Administration escalated economic warfare (“sanctions”) against many countries around the globe.

We ask you to begin a new era in U.S. relations with the world by lifting all U.S. economic sanctions.

U.S. economic sanctions impact one-third of the world’s population in 39 countries.

These sanctions block shipments and purchases of essential medicines, testing equipment, PPE, vaccines and even basic food. Sanctions also cause chronic shortages of basic necessities, economic dislocation, chaotic hyperinflation, artificial famines, disease, and poverty, leading to tens of thousands of deaths. It is always the poorest and the weakest – infants, children, the chronically ill and the elderly – who suffer the worst impact of sanctions.

Sanctions are illegal. They are a violation of international law and the United Nations Charter. They are a crime against humanity used, like military intervention, to topple popular governments and movements.

The United States uses its military and economic dominance to pressure governments, institutions and corporations to end all normal trade relations with targeted nations, lest they risk asset seizures and even military action.

The first step toward change must be an end to the U.S.’ policies of economic war. We urge you to end these illegal sanctions on all countries immediately and to reset the U.S.’ relations with the world.

Add your name - Click here to sign the petition:

https://sanctionskill.org/petition/

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Resources for Resisting Federal Repression

Since June of 2020, activists have been subjected to an increasingly aggressive crackdown on protests by federal law enforcement. The federal response to the movement for Black Lives has included federal criminal charges for activists, door knocks by federal law enforcement agents, and increased use of federal troops to violently police protests.

The NLG National Office is releasing this resource page for activists who are resisting federal repression. It includes a link to our emergency hotline numbers, as well as our library of Know-Your-Rights materials, our recent federal repression webinar, and a list of some of our recommended resources for activists. We will continue to update this page.

Please visit the NLG Mass Defense Program page for general protest-related legal support hotlines run by NLG chapters.

Emergency Hotlines

If you are contacted by federal law enforcement you should exercise all of your rights. It is always advisable to speak to an attorney before responding to federal authorities.

State and Local Hotlines

If you have been contacted by the FBI or other federal law enforcement, in one of the following areas, you may be able to get help or information from one of these local NLG hotlines for:

- Portland, Oregon: (833) 680-1312

- San Francisco, California: (415) 285-1041 or fbi_hotline@nlgsf.org

- Seattle, Washington: (206) 658-7963

National Hotline

If you are located in an area with no hotline, you can call the following number:

Know Your Rights Materials

The NLG maintains a library of basic Know-Your-Rights guides.

- Know Your Rights During Covid-19

- You Have The Right To Remain Silent: A Know Your Rights Guide for Encounters with Law Enforcement

- Operation Backfire: For Environmental and Animal Rights Activists

WEBINAR: Federal Repression of Activists & Their Lawyers: Legal & Ethical Strategies to Defend Our Movements: presented by NLG-NYC and NLG National Office

We also recommend the following resources:

Center for Constitutional Rights

Civil Liberties Defense Center

- Grand Juries: Slideshow

Grand Jury Resistance Project

Katya Komisaruk

Movement for Black Lives Legal Resources

Tilted Scales Collective

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Michael D’Onofrio - March 8, 2021

https://www.phillytrib.com/news/local_news/mumia-abu-jamal-loses-30-pounds-while-recovering-from-covid-19/article_c5da1e74-7639-5161-8558-57a7d68a2dd8.html

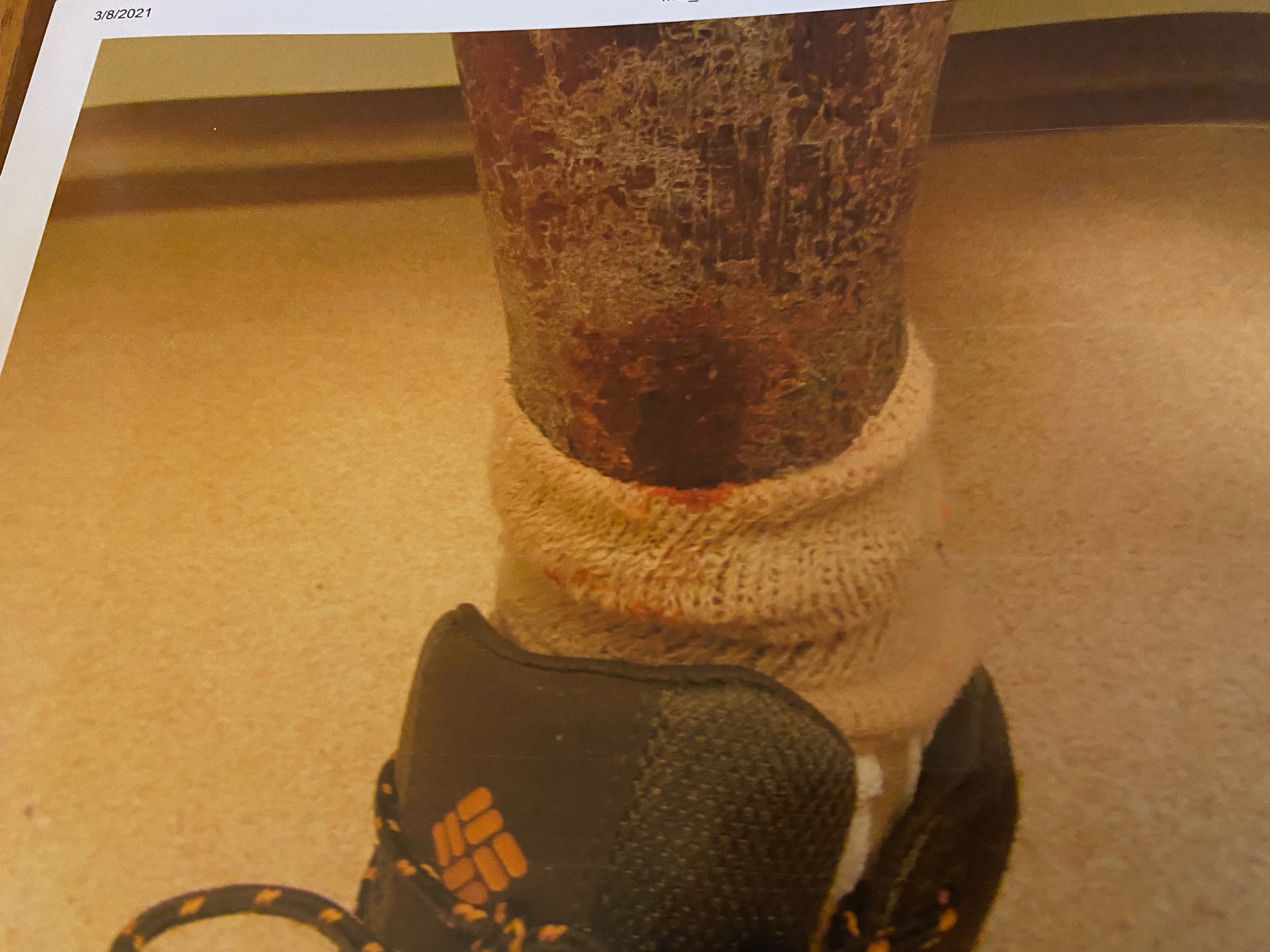

Mumia Abu-Jamal has lost 30 pounds since testing positive for COVID-19 as a long-term skin condition has flared up leaving “bloodied open wounds” all over his body, said one of his supporters.

On Monday, Abu-Jamal appeared to be recovering from COVID-19 and no longer receiving intravenous fluids as he remained isolated in the infirmary at Mahanoy State Correctional Institution in Frackville, said Johanna Fernández, an associate professor of history at Baruch College of the City University of New York.

Fernández said Abu-Jamal’s body weight has dropped to 215 pounds from 245 pounds since receiving a positive COVID-19 test on March 3.

After speaking with Abu-Jamal directly on Sunday, Fernández said, “It seems that the worst of COVID is behind us,” although she was not a medical doctor.

Yet a skin condition, which is thought to be linked to Abu-Jamal’s hepatitis C infection, has left much of Abu-Jamal’s skin cracked, whitened, bloodied and ruptured, Fernández said. While Fernández said she had photos of Abu-Jamal’s condition, she did not have permission to share them.

“It’s a horror show,” Fernández said about Abu-Jamal’s condition.

Fernández said Abu-Jamal related to her that infirmary staff ought to be giving him daily medical baths to treat his skin condition, per a prison doctor’s recommendation over the weekend. Abu-Jamal was not receiving those daily medical baths.

Fernández said Abu-Jamal remains positive.

“He wants to live,” Fernández said.

Robert Boyle, an attorney for Abu-Jamal, did not immediately return a call seeking comment.

Fernández reiterated her calls and those of Abu-Jamal’s supporters that he should be released from prison and receive medical care at a hospital.

“That a prisoner is being held under these conditions suggests that all standards of decency, morality and humanity have eroded in American society,” Fernández said. “Mumia is not alone: This is what medical care looks like in American prisons.”

Abu-Jamal was rushed to a local area hospital on Feb. 27. Soon after, he was diagnosed with congestive heart disease.

Abu-Jamal was returned to Mahanoy SCI early last week. On Wednesday, it was revealed Abu-Jamal tested positive for COVID-19.

Abu-Jamal, formerly known as Wesley Cook, was convicted of fatally shooting Philadelphia police officer Daniel Faulkner after Faulkner had reportedly pulled over Abu-Jamal’s brother during a late-night traffic stop in 1981.

In prison since 1982, Abu-Jamal was on death row until 2011, when his death sentence was ruled unconstitutional. He is now serving a life sentence.

Abu-Jamal and his supporters have always maintained his innocence, alleging that his trial was tainted by police corruption and racism. Yet Police Benevolent Association Lodge 5 and Maureen Faulkner, Daniel Faulkner’s widow, among several others have maintained the trial was fair and Abu-Jamal guilty.

Abu-Jamal, who worked in Black radio before his conviction, has published several books and commentaries during his decades in prison.

He is appealing his conviction in Pennsylvania courts.

Questions and comments may be sent to info@freedomarchives.org

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

By Nicholas Bogel-Burroughs, March 11, 2021

The judge overseeing the trial of Derek Chauvin, the former Minneapolis police officer charged with killing George Floyd, has allowed prosecutors to add an additional charge of third-degree murder against Mr. Chauvin, who is already facing a more serious count of second-degree murder.

The decision on Thursday most likely ended a sequence of legal wrangling and cleared the way for the trial to move forward. Jury selection is well underway, with five of 12 jurors already seated, and opening arguments are scheduled to begin on March 29.

The jurors will now have an additional murder charge on which they could convict, even if they decide the evidence does not support second-degree murder.

Third-degree murder was the first charge Mr. Chauvin faced last year when he was fired by the Minneapolis Police Department and arrested after Mr. Floyd’s death on May 25, and prosecutors had sought to reinstate it.

Within days of Mr. Chauvin’s arrest, he agreed to plead guilty to third-degree murder, The New York Times reported last month, but William P. Barr, then the U.S. attorney general, stepped in to reject the agreement, which had also included an assurance that Mr. Chauvin would not face federal civil rights charges.

Judge Peter A. Cahill, who is overseeing the trial, later dismissed that charge, but he upheld the more severe charge of second-degree murder. If convicted of second-degree murder, Mr. Chauvin would likely face about 11 to 15 years in prison, though the maximum penalty is up to 40 years. The maximum penalty for the added third-degree murder charge is 25 years in prison. Mr. Chauvin also faces a lesser charge of second-degree manslaughter.

The Minnesota Court of Appeals last week ordered Mr. Cahill to reconsider whether to add the third-degree murder charge, which has historically been understood to apply to defendants who commit an act that endangers multiple people. But the appeals court broadened the scope of the law in a decision this year and said the charge could be used in cases where only one person was in danger — as it was in the conviction of a Minneapolis police officer, Mohamed Noor, for a fatal shooting.

Judge Cahill said in February that he was not bound by that new interpretation because it could still be reviewed by a higher court, but the appeals court disagreed with his analysis. Judge Cahill granted the prosecutors’ motion to add the charge after brief arguments on Thursday morning from Eric J. Nelson, who is Mr. Chauvin’s lawyer, and Neal Katyal, a former solicitor general who is helping prosecutors in the case.

Mr. Chauvin, 44, has been free on bail since October and has been present in court since the trial moved ahead this week, wearing a suit and mask and taking notes on a yellow legal pad as his lawyer and prosecutors interview prospective jurors. So far, the five selected jurors include three white men, one Black man and a woman of color.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Javier Castillo Maradiaga was freed this week after 15 months in federal detention. New York had turned him over to ICE in error.

By Annie Correal and Ed Shanahan, March 11, 2021

Javier Castillo Maradiaga was on his way to a family birthday party in the Bronx in December 2019 when the police arrested him for jaywalking.

So began a 15-month odyssey during which he was locked up and flown between detention centers around the United States after New York City authorities failed to honor a law meant to keep undocumented immigrants from routinely falling into federal immigration authorities’ hands.

It was not until Wednesday, after city officials had admitted their blunder and joined activists, federal lawmakers and Mr. Castillo’s lawyers to push for his release, that he was freed from a New Jersey detention center on a federal judge’s order.

The unusual case highlights the tensions at play in recent years between a wide-ranging crackdown on undocumented immigrants by federal authorities and efforts in some jurisdictions to shield such residents with so-called sanctuary policies, which prevent state and local law enforcement agencies from collaborating with federal immigration authorities.

It also shows how little it can take for such efforts to fall short.

Mr. Castillo, 27, moved to New York from Honduras as a child to reunite with his mother. He received temporary relief from deportation under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, or DACA, which began in 2012, a year after he graduated from high school; he and two siblings became legal U.S. residents.

But his status lapsed, and, fearing deportation after President Donald J. Trump was elected and the DACA program’s future became cloudy, he did not reapply. That made him an undocumented immigrant when the police stopped him.

After being brought to the local precinct, Mr. Castillo was taken to a courthouse, officials said. The next day, the city’s Department of Correction transferred him to Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, contrary to a city policy banning such transfers in most cases.

New York law enforcement officials are not supposed to turn people over to ICE or hold them on the federal agency’s behalf, even when ICE has made a so-called detainer request. There are exceptions for those who have been convicted of violent or serious crimes or who have been identified as possibly matching people listed in a terrorist-screening database.

In the 12 months starting in July 2019, city records show, the Correction Department turned 20 people over to ICE. Of those, Mr. Castillo was the only one who had not been convicted of a violent or serious crime. He was also the only person known to have been transferred to ICE under such circumstances since the city’s sanctuary policy took effect in 2015, officials said.

“Mr. Maradiaga’s transfer to ICE was an egregious mistake and a clear violation of local law,” a spokeswoman for Mayor Bill de Blasio said in a statement, adding that officials had taken “immediate measures to ensure accountability for this misconduct, including officer discipline and clear procedural changes in how cases are reviewed. This will not happen again.”

The New Yorker reported on the city’s mistake last month.

An internal Correction Department inquiry found that the mistaken transfer was the fault of a single employee, who was suspended and then transferred to a different unit, officials said. Other steps were also taken to guard against similar foul-ups in the future, officials said.

In a letter to the Justice Department last month, the city’s corporation counsel, James E. Johnson, noted that the “operational error” that had resulted in Mr. Castillo’s detention had “been addressed,” and he argued for Mr. Castillo’s release.

By then, Mr. Castillo had been in ICE custody for more than a year, mainly at a jail in New Jersey, where he was held for the duration of the pandemic. The jaywalking charges had been dismissed, and a lawyer hired by the family was continuing to pursue his immigration case.

With a new administration taking office in January, his fate became intertwined with its policies. Despite a 100-day moratorium on deportations ordered by President Biden, Mr. Castillo was sent to Louisiana in January, where, relatives said, he believed he was on the verge of being deported.

ICE subsequently returned him to New York, but he was soon sent back to Louisiana after a federal judge in Texas temporarily blocked Mr. Biden’s moratorium.

At a Feb. 6 rally in Manhattan, Mr. Castillo’s mother, Alma Maradiaga, recounted getting frantic calls from her son as he was flown around the country amid the changing policies, despite the ongoing threat of the coronavirus.

She said he told her that he was scheduled to be flown out to Honduras and that she should arrange to have someone meet him there — only to learn later that he was not leaving.

“Back and forth,” Ms. Maradiaga, who works at a Manhattan hospital, said of ICE’s shifting positions. Mr. Castillo, she said, described it as: “‘They’re sending me; they’re not.’”

“They bullied my son every minute,” she said of ICE.

Beginning in January, with Mr. Castillo’s deportation appearing imminent, several Democratic members of New York’s congressional delegation, including Representative Ritchie Torres, urged ICE to release him. They noted that he could reapply for DACA if he were released but that ICE policy prohibited him from doing so while he was in custody.

ICE declined to release him, but his lawyers obtained a 30-day reprieve from deportation. That gave them time to seek legal remedies that might allow him to stay in the country. The federal judge’s order means those efforts can proceed.

“I’m grateful for the release of Javier, but the threat of deportation, separate and apart from the act itself, is traumatic,” Mr. Torres said in a phone interview Wednesday evening. “I find it senseless. It is nightmarish. It is Kafkaesque.”

On Wednesday, an ICE spokesman acknowledged that Mr. Castillo had been released based on the court order. Mr. Castillo was eligible for deportation because he had entered the United States unlawfully as a child in 2002 and had failed to comply with a voluntary departure order two years later, the spokesman said.

Mr. Castillo’s lawyers’ motions to reopen his immigration case had twice been denied by an immigration judge, the ICE spokesman said. The Board of Immigration Appeals is now considering a motion to reopen the case, the spokesman said.

On Wednesday, after her brother had been released from detention, Mr. Castillo’s sister, Dariela Moncada Maradiaga, hailed the judge’s order. But, in remarks streamed over Instagram, she noted that millions of other undocumented immigrants were still detained or otherwise in legal limbo.

“Javier is out,” Ms. Moncada said, briefly turning the camera toward her brother and saying that they both planned to speak at a rally this weekend in Brooklyn. “But we still have to worry about those other 11 million.”

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

For years we’ve been crediting endorphins, but it’s really about the endocannabinoids.

By Gretchen Reynolds, March 10, 2021

We can stop crediting endorphins, the natural opioid painkillers produced by our bodies, for the floaty euphoria we often feel during aerobic exercise, according to a nifty new study of men, women and treadmills. In the study, runners developed a gentle intoxication, known as a runner’s high, even if researchers had blocked their bodies’ ability to respond to endorphins, suggesting that those substances could not be behind the buzz. Instead, the study suggests, a different set of biochemicals resembling internally homegrown versions of cannabis, better known as marijuana, are likely to be responsible.

The findings expand our understanding of how running affects our bodies and minds, and also raise interesting questions about why we might need to be slightly stoned in order to want to keep running.

In surveys and studies of experienced distance runners, most report developing a mellow runner’s high at least sometimes. The experience typically is characterized by loose-limbed blissfulness and a shedding of anxiety and unease after half an hour or so of striding. In the 1980s, exercise scientists started attributing this buzz to endorphins, after noticing that blood levels of the natural painkillers rise in people’s bloodstreams when they run.

More recently, though, other scientists grew skeptical. Endorphins cannot cross the blood-brain barrier, because of their molecular structure. So, even if runners’ blood contains extra endorphins, they will not reach the brain and alter mental states. It also is unlikely that the brain itself produces more endorphins during exercise, according to animal studies.

Endocannabinoids are a likelier intoxicant, these scientists believed. Similar in chemical structure to cannabis, the cannabinoids made by our bodies surge in number during pleasant activities, such as orgasms, and also when we run, studies show. They can cross the blood-brain barrier, too, making them viable candidates to cause any runner’s high.

A few past experiments had strengthened that possibility. In one notable 2012 study, researchers coaxed dogs, people and ferrets to run on treadmills, while measuring their blood levels of endocannabinoids. Dogs and humans are cursorial, meaning possessed of bones and muscles well adapted to distance running. Ferrets are not; they slink and sprint but rarely cover loping miles, and they did not produce extra cannabinoids while treadmill running. The dogs and people did, though, indicating that they most likely were experiencing a runner’s high and it could be traced to their internal cannabinoids.

That study did not rule out a role for endorphins, however, as Dr. Johannes Fuss realized. The director of the Human Behavior Laboratory at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf in Germany, he and his colleagues had long been interested in how various activities affect the inner workings of the brain, and after reading the ferret study and others, thought they might look more closely into the runner’s high.

They began with mice, which are eager runners. For a 2015 study, they chemically blocked the uptake of endorphins in the animals’ brains and let them run, then did the same with the uptake of endocannabinoids. When their endocannabinoid system was turned off, the animals ended their runs just as anxious and twitchy as they had been at the start, suggesting that they had felt no runner’s high. But when their endorphins were blocked, their behavior after running was calmer, relatively more blissed-out. They seemed to have developed that familiar, mild buzz, even though their endorphin systems had been inactivated.

Mice emphatically are not people, though. So, for the new study, which was published in February in Psychoneuroendocrinology, Dr. Fuss and his colleagues set out to replicate the experiment, to the extent possible, in humans. Recruiting 63 experienced runners, male and female, they invited them to the lab, tested their fitness and current emotional states, drew blood and randomly assigned half to receive naloxone, a drug that blocks the uptake of opioids, and the rest, a placebo. (The drug they had used to block endocannabinoids in mice is not legal in people, so they could not repeat that portion of the experiment.)

The volunteers then ran for 45 minutes and, on a separate day, walked for the same amount of time. After each session, the scientists drew blood and repeated the psychological tests. They also asked the volunteers whether they thought they had experienced a runner’s high.

Most said yes, they had felt buzzed during the run, but not the walk, with no differences between the naloxone and placebo groups. All showed increases, too, in their blood levels of endocannabinoids after running and equivalent changes in their emotional states. Their euphoria after running was greater and their anxiety less, even if their endorphin system had been inactivated.

Taken as a whole, these findings are a blow to endorphins’ image. “In combination with our research in mice,” Dr. Fuss says, “these new data rule out a major role for endorphins” in the runner’s high.

The study does not explain, though, why a runner’s high exists at all. There was no walker’s high among the volunteers. But Dr. Fuss suspects the answer lies in our evolutionary past. “When the open savannas stretched and forests retreated,” he says, “it became necessary for humans to hunt wild animals by long-distance running. Under such circumstances, it is beneficial to be euphoric during running,” a sensation that persists among many runners today, but with no thanks due, it would seem, to endorphins.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

An independent report commissioned by the Los Angeles City Council faulted the department for its lack of planning and chaotic response.

By Nicholas Bogel-Burroughs, John Eligon and Will Wright, March 11, 2021

The Los Angeles Police Department severely mishandled protests last summer in the wake of George Floyd’s death, illegally detaining protesters, issuing conflicting orders to its rank-and-file officers and striking people who had committed no crimes with rubber bullets, bean bags and batons, according to a scathing report released on Thursday.

An ill-prepared department quickly allowed the situation to spiral out of control when some protesters got violent, failing to rein in much of the most destructive behavior while arresting thousands of protesters for minor offenses, according to the 101-page report commissioned by the City Council.

The report was also highly critical of the department’s leadership, saying that high-ranking officers sometimes made chaotic scenes even worse by shifting strategies without communicating clearly. In many cases, officers used “antiquated tactics” that failed to calm the more violent demonstrators, some of whom the report said deliberately threw things at officers from behind a line of peaceful protesters.

The review is the latest to find serious fault with a police department’s response to the wave of protests that swept the country in the wake of Mr. Floyd’s death in Minneapolis on May 25.

From New York to Chicago to Dallas, investigations in the past several months have found that police departments nationwide botched their handling of the protests. In city after city, officers, under faulty supervision, ignored protocols and used excessive force on demonstrators. Mass arrests swept up people who were not breaking any laws. And aggressive responses caused gatherings to quickly descend into chaos.

In New York, one highly critical report last year found that the Police Department, the nation’s largest force, badly mishandled the mass demonstrations, in part by sending untrained officers into marches.

“The response really was a failure on many levels,” Margaret Garnett, the commissioner for the New York City Department of Investigation, said at the time.

In Chicago, an inspector general’s report found that officers had failed to wear body cameras as required and underreported how many times they used their batons to strike protesters. Dallas police officers were found to have fired pepper balls at peaceful marchers. And in Philadelphia, a report condemned an unprepared police response in which officers fueled unrest in some predominantly Black areas with excessive force against demonstrators, while allowing white men armed with bats and pipes to confront protesters in other parts of town.

In Los Angeles, undercover officers blended into the protests but then had no way to report criminal behavior directly to supervisors. Sometimes they had to be rescued from the devolving crowd, the report said, adding that the department’s intelligence operations have become less effective as positions in that field were cut in favor of patrol units.

And although officers arrested thousands of people during the protests in late May, there was no clear plan for how to detain and process them, according to the report. Some protesters were injured so severely by “less lethal” munitions — like rubber bullets and pepper balls — that they had to get surgery.

The Los Angeles Police Department said in a statement that its chief, Michel Moore, had “taken responsibility for activities over the summer,” and that the department had provided crowd control training to its officers after the summer unrest.

“The opportunity to learn from our mistakes, to grow, and become better servants to our community is something that has been embraced and we look forward to leaning into the challenges and being better,” the statement said.

RJ Dawson, who took part in the protests in Los Angeles as part of an activist group, said he had little hope that the report would lead to significant changes.

“I find that these reports tell us what we already know,” he said. “When you’re out here, you see the civil rights violations.”

The review, one of three investigations into the department’s response to the demonstrations, was completed by a panel of former police commanders and led by Gerald Chaleff, who has served on police oversight panels in Los Angeles dating back to the city’s 1992 riots after four officers were acquitted in the beating of Rodney King.

“There was a lack of preparation, a lack of planning,” Mr. Chaleff said of the Los Angeles Police Department in an interview, adding that it “could have minimized” the destruction caused by a small group of people who vandalized the city during last year’s protests.

He said that most demonstrators were peaceful, but that “there were some people there to create chaos and cause problems.”

In interviews, several commanders admitted to the authors of the report that they lacked experience in managing peaceful protests and said they did not receive enough training to maintain order.

Training in crowd control, which became mandatory after the police responded violently in 2007 to demonstrations over immigrant rights, had not occurred for several years leading up to 2020, according to the report. There are “still a few high-level personnel” with expertise in handling large demonstrations, but the report said the Police Department should prioritize the training going forward, as officers retire and are assigned elsewhere.

Officers interviewed for the report said they thought that “good relationships” with residents would keep the demonstrations peaceful, as they had in the recent past, but that their confidence resulted in them failing to plan.

The department formed lines of officers standing shoulder to shoulder to block off a street or keep the protesters from going a certain way. But this technique proved ineffective. As violence erupted, the lines did nothing to help control the crowd.

Across the country, reports have consistently shown similar failures.

In New York, more than 2,000 people were arrested during the city’s first week of demonstrations and enforcement during the height of the protests was overly aggressive and disproportionately affected people of color, according to the highly critical report, which was issued by the state’s attorney general, Letitia James. Her office received more than 1,300 complaints of police misconduct stemming from those first weeks of protest in New York City, she said.

In Portland, Ore., Justice Department lawyers wrote last month that the city’s police department was out of compliance with a 2014 settlement agreement that focused in part on how officers used force. The Justice Department wrote in court that during protests last year, the Portland Police Bureau used force more than 6,000 times in six months, at times deviating from policy.

In Seattle, the city’s Office of Inspector General has been working on a review of last year’s protests, saying there were more than 120 separate protest events and more than 19,000 complaints about how they were handled.

In Chicago, the city’s inspector general report found that the Police Department’s senior leadership had failed the public and rank-and-file officers in its handling of intense protests. As in Los Angeles, the department failed to properly process mass arrests, the report said, overcharging some people and undercharging others. Officers obscured their badge numbers and name plates, and many did not wear body cameras, making it difficult to hold officers accountable for misconduct.

All this happened as the public’s own footage of questionable tactics by Chicago officers circulated widely, the report said. The city and the Police Department, the report said, may have been set “back significantly in their long-running, deeply challenged effort to foster trust with members of the community.”

The Dallas Police Department also came under close scrutiny for how it handled protests. A Dallas Morning News report found that the police had improperly fired pepper balls at protesters. A federal judge had issued a temporary restraining order preventing officers from using chemical agents, flash-bang grenades and other less-lethal weapons against protesters. The police chief at the time ended up resigning, though she said it was for reasons other than the criticism of the protest response.

Mr. Chaleff, who once served as the Los Angeles Police Department’s special assistant for constitutional policing under former Chief William J. Bratton, who later led the New York Police Department, noted that Thursday’s report was primarily concerned with the institutional response, not with any particular incident of police misconduct, a sign that the police had “allowed less violence” than in the past.

“I think there’s been progress,” he said. “But you have to be prepared for what’s coming, and you have to have the elected and appointed leadership that understands what is required and creates a culture for the kinds of responses that are necessary.”

Reporting was contributed by Mike Baker, Manny Fernandez, Shawn Hubler and Ali Watkins.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

The pandemic relief bill includes $2.75 billion for private schools. How it got there is an unlikely political tale, involving Orthodox Jewish lobbying, the Senate majority leader and a teachers’ union president.

By Erica L. Green, March 13, 2021

WASHINGTON — Tucked into the $1.9 trillion pandemic rescue law is something of a surprise coming from a Democratic Congress and a president long seen as a champion of public education — nearly $3 billion earmarked for private schools.

More surprising is who got it there: Senator Chuck Schumer of New York, the majority leader whose loyalty to his constituents diverged from the wishes of his party, and Randi Weingarten, the leader of one of the nation’s most powerful teachers’ unions, who acknowledged that the federal government had an obligation to help all schools recover from the pandemic, even those who do not accept her group.

The deal, which came after Mr. Schumer was lobbied by the powerful Orthodox Jewish community in New York City, riled other Democratic leaders and public school advocates who have spent years beating back efforts by the Trump administration and congressional Republicans to funnel federal money to private schools, including in the last two coronavirus relief bills.

Democrats had railed against the push by President Donald J. Trump’s education secretary, Betsy DeVos, to use pandemic relief bills to aid private schools, only to do it themselves.

And the private school provision materialized even after House Democrats expressly sought to curtail such funding by effectively capping coronavirus relief for private education in the bill at about $200 million. Mr. Schumer, in the 11th hour, struck the House provision and inserted $2.75 billion — about 12 times more funding than the House had allowed.

“We never anticipated Senate Democrats would proactively choose to push us down the slippery slope of funding private schools directly,” said Sasha Pudelski, the advocacy director at AASA, the School Superintendents Association, one of the groups that wrote letters to Congress protesting the carve-out. “The floodgates are open and now with bipartisan support, why would private schools not ask for more federal money?”

Mr. Schumer’s move created significant intraparty clashes behind the scenes as Congress prepared to pass one of the most critical funding bills for public education in modern history. Senator Patty Murray, the chairwoman of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, was said to have been so unhappy that she fought to secure last-minute language that stipulated the money be used for “nonpublic schools that enroll a significant percentage of low‐income students and are most impacted by the qualifying emergency.”

“I’m proud of what the American Rescue Plan will deliver to our students and schools and in this case specifically, I’m glad Democrats better targeted these resources toward students the pandemic has hurt the most,” Ms. Murray said in a statement.

Jewish leaders in New York have long sought help for their sectarian schools, but resistance in the House prompted them to turn to Mr. Schumer, said Nathan J. Diament, the executive director for public policy at the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America, who contended that public schools had nothing to complain about.

“It’s still the case that 10 percent of America’s students are in nonpublic schools, and they are just as impacted by the crisis as the other 90 percent, but we’re getting a much lower percentage overall,” he said, adding, “We’re very appreciative of what Senator Schumer did.”

Mr. Schumer faced pressure from a range of leaders in New York’s private school ecosystem, including from the Catholic Church.

In a statement to Jewish Insider, Mr. Schumer said, “This fund, without taking any money away from public schools, will enable private schools, like yeshivas and more, to receive assistance and services that will cover Covid-related expenses they incur as they deliver quality education for their students.”

The magnitude of the overall education funding — more than double the amount of schools funding allocated in the last two relief bills combined — played some part in the concession that private schools should continue to receive billions in relief funds. The $125 billion in funding for K-12 education requires districts to set aside percentages of funding to address learning loss, invest in summer school and other programming to help students recover from educational disruptions during the pandemic.

The law also targets long-underserved students, allocating $3 billion in funding for special education programming under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, and $800 million in dedicated funding to identify and support homeless students.

“Make no mistake, this bill provides generous funding for public schools,” a spokesman for Mr. Schumer said in a statement. “But there are also many private schools which serve large percentages of low-income and disadvantaged students who also need relief from the Covid crisis.”

Proponents of the move argue that it was merely a continuation of the same amount afforded to private schools — which also had access to the government’s aid program for small businesses earlier in the pandemic — in a $2.3 trillion catchall package passed in December. But critics noted that was when Republicans controlled the Senate, and Democrats had signaled they wanted to take a different direction. They also contend that Mr. Schumer’s decision came at the expense of public education, given that the version of the bill that initially passed the House had about $3 billion more allocated for primary and secondary schools.

Mr. Schumer’s move caught his Democratic colleagues off guard, according to several people familiar with deliberations, and spurred aggressive efforts on the part of advocacy groups to reverse it. The National Education Association, the nation’s largest teachers’ union and a powerful ally of the Biden administration, raised its objections with the White House, according to several people familiar with the organization’s efforts.

In a letter to lawmakers, the association’s director of government affairs wrote that while it applauded the bill, “we would be remiss if we did not convey our strong disappointment in the Senate’s inclusion of a Betsy DeVos-era $2.75 billion for private schools — despite multiple avenues and funding previously made available to private schools.”

Among the Democrats who were displeased with Mr. Schumer’s reversal was Speaker Nancy Pelosi of California, who told him that she preferred the provision Democrats had secured in the House version, according to people familiar with their conversation. They also said Representative Robert C. Scott, the chairman of the House education committee, was “very upset” about both the substance and the process of Mr. Schumer’s revision, and had his staff communicate that he was “insulted.”

Integral to swaying Democrats to go along, particularly Ms. Pelosi, was Ms. Weingarten, several people said. Ms. Weingarten reiterated to the speaker’s office what she expressed to Mr. Schumer’s when he made his decision: Not only would she not fight the provision, but it was also the right thing to do.

Last year, Ms. Weingarten led calls to reject orders from Ms. DeVos to force public school districts to increase the amount of federal relief funding they share with private schools, beyond what the law required to help them recover.

At the time, private schools were going out of business everyday, particularly small schools that served predominantly low-income students, and private schools were among the only ones still trying to keep their doors open for in-person learning during the pandemic.

But Ms. Weingarten said Ms. DeVos’s guidance “funnels more money to private schools and undercuts the aid that goes to the students who need it most” because the funding could have supported wealthy students.

This time around, Ms. Weingarten changed her tune.

In an interview, she defended her support of the provision, saying that it was different from previous efforts to fund private schools that she had protested under the Trump administration, which sought to carve out a more significant percentage of funding and use it to advance private school tuition vouchers. The new law also had more safeguards, she said, such as requiring that it be spent on poor students and stipulating that private schools not be reimbursed.

“The nonwealthy kids that are in parochial schools, their families don’t have means, and they’ve gone through Covid in the same way public school kids have,” Ms. Weingarten said.

“All of our children need to survive, and need to recover post-Covid, and it would be a ‘shonda’ if we didn’t actually provide the emotional support and nonreligious supports that all of our children need right now and in the aftermath of this emergency,” she said, using a Yiddish word for shame.

Mr. Diament likened Mr. Schumer’s decision to Senator Edward M. Kennedy’s move more than a decade ago to include private schools in emergency relief funding if they served students displaced by Hurricane Katrina.

Mr. Diament said that he did not expect that private schools would see this as a precedent to seek other forms of funding.

“In emergency contexts, whether they’re hurricanes, earthquakes, or global pandemics, those are situations where we need to all be in this together,” he said. “Those are exceptional situations, and that’s how they should be treated.”

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

The settlement is one of the largest of its kind, but it may make it harder to seat an impartial jury for the trial of Derek Chauvin, the former officer charged with murder in Mr. Floyd’s death.

By Nicholas Bogel-Burroughs and John Eligon, March 12, 2021

The City of Minneapolis agreed on Friday to pay $27 million to the family of George Floyd, the Black man whose death set off months of protests after a video showed a white police officer kneeling on his neck.

The payment to settle the family’s lawsuit was among the largest of its kind, and it came as the officer, Derek Chauvin, was set to go on trial this month for charges including second-degree murder. As the settlement was announced by city officials and lawyers for Mr. Floyd’s family, Mr. Chauvin sat in a courtroom less than a mile away, where jurors were being selected for his trial.

Mayor Jacob Frey called the agreement a milestone for Minneapolis’s future. Ben Crump, the civil rights lawyer who is among those representing Mr. Floyd’s family, said it could set an example for other communities.

“After the eyes of the world rested on Minneapolis in its darkest hour, now the city can be a beacon of hope and light and change for cities across America and across the globe,” he said.

But legal experts said the agreement might make it even harder to seat an impartial jury in the case against Mr. Chauvin, which was already a challenge because of the attention given to Mr. Floyd’s death and the intense demonstrations that followed. In the first four days of jury selection this week, nearly all of the potential jurors said they had seen the video of his arrest, including all but one of the seven selected for the trial so far.

Mary Moriarty, the former chief public defender in Minneapolis, said that the timing could hardly be worse for the court case and that Mr. Chauvin’s lawyers might even ask for a mistrial.

She added that the defense team might have reason to worry that jurors’ views could be affected by the deal, if they saw it as an indication that Mr. Chauvin’s actions were inappropriate. Mr. Chauvin’s lawyer and a spokesman for the state attorney general’s office, which is prosecuting the case, did not respond to requests for comment. A spokeswoman for Minneapolis said the settlement was “independent and separate from the criminal trial underway.”

The large payment was a sign of the magnitude of the response to Mr. Floyd’s death, which led to protests in hundreds of cities, changes in local and state laws and a reckoning over racism and police abuse. In Minneapolis, a police station and many businesses were burned over several nights of unrest.

At a news conference, Mr. Crump said the agreement would “allow healing to begin” in the city. He said the family had pledged to donate $500,000 to “lift up” the neighborhood around 38th Street and Chicago Avenue, the corner where the police confronted Mr. Floyd on May 25. The officers had arrived after a store clerk called 911 and said that Mr. Floyd had tried to pay with a fake $20 bill.

Mayor Frey said on Twitter that the agreement “reflects a shared commitment to advancing racial justice and a sustained push for progress.”

Some community members, however, were skeptical of his assertion.

“We haven’t even taken a step, let alone a mile, toward fundamentally changing this police force,” said D.A. Bullock, a filmmaker who lives in Minneapolis. “We’re just waiting for the next George Floyd to happen.”

Mr. Bullock said he imagined that Mr. Floyd’s family would return every penny if they could have him back.

“All I want to talk about is how we’re not going to have police out here killing Black folks,” he said. “That’s really my bottom line, regardless of the size of the settlement.”

Two years ago, Minneapolis agreed to pay $20 million to the family of Justine Ruszczyk, a white yoga instructor who was fatally shot by Mohamed Noor, a police officer who is Somali. Excluding that case, the agreement with the Floyd family is larger than the city’s combined settlements related to police misconduct from 2006 to 2020, according to city data.

Minneapolis pays its settlements out of a fund for legal payouts and workers’ compensation claims, and residents have expressed concern that their taxes are subsidizing payments for the misconduct of the police while failing to hold officers accountable. Activists have pushed for legislation that would require officers to carry their own liability insurance, with premiums that could rise after cases of misconduct.

Mark Ruff, the city coordinator, said during a news conference that with cash reserves, officials were confident that the Floyd agreement would not lead to an increase in property taxes.

The settlement reflected the rise in payments over police abuse and misconduct in recent years. In September, Louisville, Ky., agreed to pay $12 million to the family of Breonna Taylor, the Black woman whom officers shot and killed in her apartment a year ago.

Five years earlier, the family of Freddie Gray reached a $6.4 million settlement with Baltimore after he was fatally injured in police custody. Also in 2015, New York agreed to pay $5.9 million to the family of Eric Garner, who died after a police officer used a chokehold on him.

In some ways, the escalating amounts are indicative of growing public support for holding the police accountable, said Katherine Macfarlane, an associate professor of law at the University of Idaho who specializes in civil rights litigation. But it is also an issue of precedent, she said.

“I think that once you have an incrementally larger settlement, it becomes, in some way, precedent to ask for at least that,” she said. “It gives an attorney a way to say, ‘This is what’s been done before on similar facts, but this is even worse, so we should go above that.’”

Mr. Floyd’s family had sued Minneapolis in July, saying that the police had violated his rights and failed to properly train its officers or fire those who violated department policies.

Mr. Crump said on Friday that the settlement was the largest ever reached before trial in a civil rights wrongful death lawsuit involving the police. That it came in a lawsuit over the death of a Black man, he said, “sends a powerful message that Black lives do matter and police brutality against people of color must end.”

Tim Arango contributed reporting from Minneapolis.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Economics offers only part of the answer. The rest depends on whether you think higher education is an investment or a public good.

By Spencer Bokat-Lindell, March 11, 2021

(Matt Huynh) Been Down So Long It Looks Like Debt to Me

An American family’s struggle for student loan redemption

Whenever I think about student loan debt, one of the first things I think about — besides my own — is a 2018 essay by my colleague M.H. Miller. As one of the 45 million Americans who collectively owe $1.71 trillion for student loans, Mr. Miller wrote about what it is like to have debt — more than $100,000 worth in his case — become the organizing principle of your life, to be incapacitated by it, suspended, at age 30, “in a state of perpetual childishness.”

A lot has changed since Mr. Miller wrote that essay. For one thing, the national student debt increased by a couple of hundred billion dollars. But the most striking difference is how quickly calls for the president to cancel that debt, a vast majority of which the federal government owns, have migrated from the margins to the center of the national policy debate, from a radical demand chanted by activists to a proposal championed by the top Democrat in the Senate.

Here’s how economists, lawmakers and activists are thinking about it.

What’s the case for canceling student debt?